by Richard Kuslan (February 2020)

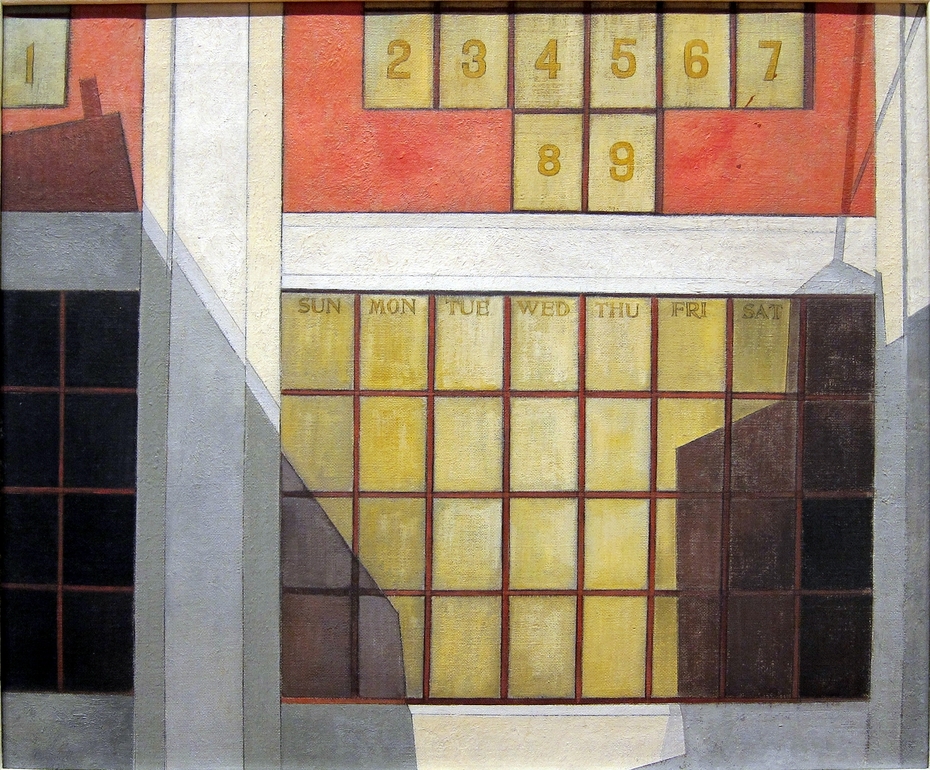

Business, Charles Demuth, 1921

Were Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy to return to life and revisit the cities and towns of the United States they once toured, they might have sighed, “All gone!”—meaning the thousands of theaters and film houses in which they had played comedy to capacity audiences from 1915 to 1950. Were they to watch the shows presented in the name of comedy today, they might have shouted, “What a shame!” before gladly returning to the footlights in the sky, because little remains today that even resembles comedy though it calls itself comedy. The American version of the popular television show franchise, The Office, masquerades as a comedy. The show is an egregious example of what American television palms off as comedy, but which is a perversion of comedy.

Its writers have placed “the office” of about a dozen employees in a regional sales department of a company they have named Dunder-Mifflin and located in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Its staff sells paper. Even before dialogue is uttered, the writers have set the stage for ridicule. Piffling dunderheads selling an unuttered but patently assumed useless relic of the before hi-tech old world in a proverbial backwater—a town the show never credits even sentimentally with once having roared with industry—deserve, in the writers’ view, relentless, resentful sarcasm.

Read more in New English Review:

• The Inverted Age

• Desert Island Triggers

• China’s Growing Biotech Threat

There is misanthropy in spades. The writers set up their characters as props for derision; every slight and slander the writers choose to inflict upon them is their fate. In the “Office Olympics” episode (one typifies all), Michael, accompanied by Dwight (whose characters I treat further on in this essay), is looking to buy a condo. They stand and admire one of many identical two-story units with garage in front. Michael speaks the following lines until the italicized brackets with uncharacteristic naturalness and sensitivity, but this is a set-up, a theatrical direction in the service of a misdirection to an ironic punchline.

Michael: Home, sweet home.

Dwight: Which one’s yours?

Michael: Right there. My sanctuary. My party pad. Someday I can just see my grandkids learning how to walk out here. Hang a swing from this tree. Push them back . . . wait . . . [Michael turns around, as does Dwight] no, it’s this one, right here. Home, sweet home.

Michael and Dwight are, of course, fictions. One might indulge in a chortle at the expense of the fictional butt of a nasty joke and shrug it off (it’s only a story) without understanding why we have laughed or the kind of laugh we have laughed or to what purpose we have been made to laugh. But since a fictional character represents an idea in the minds of the writer, we must ask, if we truly wish to understand what is meant and our reaction to it, why it is that the writers visit upon Michael the indignity of ridicule which the dialogue above, one of many such, represents? They deny him even the poignant longing for a sentimental memory of grandchildren happily at play. The writers have condemned Michael. The writers encourage us to laugh at this. They have created him to condemn him and to have their way with him. Moreover, they condemn him to a purpose: the writers want the audience to agree with them that Michael deserves his fated denial of happiness. The laugh in reaction represents our agreement.

The office leader is Michael, a manager, whom the writers have sardonically written as an empty suit, a bumbler, an incompetent, a tool, a prolific self-embarrasser; he is a loser and a loner in no way deserving of his position by merit. Just watch him play company basketball in the warehouse with feverishly sweating gung-ho unathleticism or insipidly blurt out, “That’s what she said,” to every possible reference to penile size or scream like a man on fire for the chocolate turtles missing from the gift basket and you will see how the writers have made him a facile and obvious target for derision.

But his position in the company is an iron rice bowl, no less because of the Scranton office’s insignificance, but also by virtue of his face-saving pusillanimity before the smart and dapper corporate big-wigs in the main office located in, of course, Manhattan. For Manhattan in this show is the solar disk about which distant Scranton traces a Plutonic orbit; its elite corporate bureaucrats, including similar types by analogy who produce this show, the gods who beneficently administer life and livelihood to an underworld of pathetic grotesques. The executives who are portrayed, in contradistinction, speak in measured tones, and seem level-headed and capable: They are adults in a room full of wayward children. (For some reason, which the writers don’t explain, the execs keep the Scranton office open. To play with them?) These überexecs keep Michael as the manager because he is the most useful of the useless: spineless, he will always kowtow. (In Chinese, kowtow means to “bang the head on the floor,” giving the neck so that the head atop it may be removed at the caprice of the superior.) That is why, and not because of any competence, they value him so. To assuage his sense of inferiority and presumably to keep him useful, they granted him the perk that signifies his standing, for he is the sole employee with his own office.

Anyone who is aware of the dramatic changes over the past fifty years in the Northeast of the United States understands that the Big Apple has been over for at least a generation. It has ceased to be the center for the creation and exploration of life-enhancing, thought-expanding art and ideas. The buildings still stand, but no longer does their skyscraping point to the civilizational aspirations they once stood for. However, when The Office plays in proverbial Peoria, where the local idea of the Coasts may be as much as a century old—the national audience will not understand that New York City has become a greenhouse of deadly nightshade.

Before the American Cultural Revolution of 1968, in less than a decade, when everyone who wanted to be anyone made a beeline to “The City,” as those who live within commuting distance call it, Manhattan’s creative climate gave rise to: In music theater alone, Hello, Dolly!West Side StoryFiddler on the RoofThe Music ManCamelotA Funny Thing Happened on the Way of the ForumThe Best ManThe Ed Sullivan Show that curated the popular best of the best; in music, Miles Davis recorded Kind of BlueJazz SambaEloise picture books for children; Truman Capote wrote Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Commercial successes, all. An exhaustive list would be encyclopedic in the manner of a funerary oration for an epic hero.

Since then though, what new popular work of comparable aesthetic quality has Manhattan given rise to? Precious little, and less even than that in the most recent decade of this century. The bubonic plague of post-modernist nihilism has swept through it, infecting its once awesome legion of intellectuals and creatives. Like Colin Wilson’s Mind Parasites, these negative, corrosive, divisive ideas have turned The City That Never Sleeps into The City That’s Woke and Gone Broke. It’s once flourishing cultural life is bankrupt, its collective back turned upon its former high-minded, high-achieving aesthetic ideals. We see an aspect of this strident ideological nihilism at work in The Office.

Furthermore, with the advent of the Internet and the demise of the necessity for creatives and taste-makers to live and work geographically close to one another, communities have become virtual and the days of dictatorial urban arbiters of art, fashion, publishing, entertainment, etc., are coming to a close. So even as a pretext, none of this set-up rings true, either within the fantasy world the writers have created or in the larger, real world they wish to portray according to their fantasy. But this state of affairs is central to understanding the supercilious and cynical mindset of the team behind the show: they have adopted New York’s former exalted status as their own without having delivered the goods by which that status was earned. The show is their propaganda. Through it, they self-aggrandize into beings superior to the characters they despise and ridicule. They want you to agree with them. That is the point of this show.

The writers flesh out The Office with the supporting cast of employees, a panoply of representative types they think exist (or perhaps wish to exist): a sensitive gay Latino; a grumpy middle-aged black man more interested in leaving the office than working; a cold, imperious blonde with a modicum of intellect; a presumably oversexed air-head subcon party girl; an overweight, past her prime, very dull white woman; a grizzled balding former hippie/weirdo, etc.

These types represent with a revelational congruence the protected class categories of age, race, sexual orientation, national origin and ethnicity set out in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, by which indiscriminate, inaccurate and facile groupings Americans are compelled by law to identify themselves (and which many have leapt to arrogantly and stridently adopt so as to reap the promised benefits inuring to “privileged” status, which they simultaneously decry when imagined in the behavior of others.). The writers see types and make segregating assumptions about humanity by classifying their characters by means of specific external indicia, such as skin color, age, sexual preference, etc., almost entirely associated with political theorizing rife among those who call themselves “Left.” So the writers do not see individuals; in fact, they’ve created none. But the point of a purportedly, a non-discriminatory cast of representative types, is this: All the fictional Americans in this show are equally subject to the writers’ ridicule.

The writers throw their poison darts at their stereotypical cardboard cut-out creations for their own amusement. So unforgiving are these writers toward their own creations that they do not even grant them the necessity of having to make a living. Presumably, 9 to 5 for life in a thankless job in a backwater is per se unforgivable. None of them is allowed any hope or expectation of bettering their lives: They have only their own wretched ordinariness, now and forever. (Which of these characters would one want as a friend—heaven forbid a member of one’s family? Not one.) And yet, here they all are, thrown together in a kind of awful purgatory. So, why are they brought together? They are the hay in the barn spread down for the thoroughbreds to defecate on.

None being a person, each is a prototype and a stereotype of someone’s idea of American loserdom. It is a loserdom consisting of those Americans whose jobs were shipped overseas, like the Scrantonites whose industrial powerhouse once provided copious opportunities for honest, productive work near home, where they would produce the goods they might themselves consume. The very “elites” —a term originally used by cold war scholars to identify high-level Communist party officials now turned against Americans—who assert the existence of this loserdom are those who have engineered the conditions that gave rise to it.

This is their “narrative” —the favored jargon of the post-modernist pseudo-intellectual when what is really meant is “I’m making up a story.” It is a narrative of blameworthiness they purport to fix upon the Scrantonites, and by extension, every American (it is an “all-inclusive cast, after all), for the failings that inure to the “elites” themselves. No mea culpas for these nihilists: it’s “tua culpa” all the way. If they could not ridicule others, they would have to ridicule themselves. But, of course, they would never deign to be introspective; gods never are.

The writers’ mock brilliance delivers the key to understanding the show: all of the characters are scapegoats who deserve their scapegoating. The Head Scapegoat, the scapegoat di tutti scapegoats, is the character Dwight Schrute. Presumably Pennsylvania Dutch by ancestry, with an ugly staccato name that calls up associations with “dweeb” and “shit,” even Dwight’s title is in doubt. He insists on being called Assistant Sales Manager; his boss, Michael, also his “best friend,” calls him the “Assistant to the Sales Manager.” (Surely this indicates that at least one writer is a Derrida-devotee de(con)structionist for whom even a two-letter preposition can be manipulated to add meaning to that which is essentially meaningless, so as to create the preferred personal “narrative.”)

Uncharitably, the writers paint Dwight in horrid shapes and colors: Immature, hyperactive, uncoordinated, incompetent, ugly, four-eyed, asocial, a dork, a jerk, a failure. He is the deserving butt of any practical joke, the weird braggart kid in second grade who would threaten to twist the arm of a kindergartener but would, since he is a klutz, end up having his own arm twisted. The writers play up his kooky “Amishness” almost as a fetish with an enormous family of similarly bearded hicks in Mr. Green Jeans jumpers who grow table beets and live in a home with an outhouse under the house, a parsimonious and dour lot who once shunned Dwight as a child for not saving the oil from canned tuna. (I’ll bet the writers recycle fastidiously in their own urban townhouses.) The portrayal of Dwight’s character, presumably a producer’s direction to the talent, is oddly flat and humorless with a shocking implication of a hackneyed stereotype of autism. All designed to demonstrate that even Loserville’s Losers (including the audience) have an Even Greater Loser of their own to mock. Dwight is the village idiot.

Incredibly, the writers even create a link between Dwight and the SS. Yes, the Nazi Party’s Schutzstaffel, the terrorizing paramilitary wing of the NSDAP. The writers have Dwight confess in passu directly to the camera that his grandfather fought for the German army and is still “puttering around in Argentina.” (Like Mengele?) Dwight, pegged as the descendant two generations removed from a Nazi, is thus ancestrally deserving of your unequivocal opprobrium.

Demographically speaking, it must be kosher to denigrate the Amish before a worldwide audience. After all, they do not watch TV (or even have electricity in their homes), so they could not possibly complain, but even if they did, their numbers are so miniscule that the producers would never field flak from the advertisers. (Do you really wish to buy anything from a company that sponsors a show such as this?) The public degradation of these people is in the clear: The suits in Manhattan do not care because it does not affect advertising revenue.

Try making Dwight Jewish: they wouldn’t dare (or would they? Is this coming next? Is Dwight the test case?). Connect the Gestapo Grandpa (or SS Zaydie?) to the mock Jewishness of the Dwight character and the viewer cannot help but to turn the nose at the pervasive stench from the scriptorial venom secreted in the details that oozes out of the cracks so unctuously. Dwight is the misanthropy magnet which the writers are hoping you will spit your laughter of disdain and derision upon. Why? To misdirect your spittle away from the writers. (I will address that in more detail below.)

As if to save the day, having populated The Office with unlovable un-people, the show’s creators, surely cognizant of the audience demographic, perform yet another sleight-of-hand to attract eye-balls for the advertisers: The introduction into their mélange of sludge-beings the Jim/Pam dyad. Consisting of a handsome masculine white male (Jim) and a shapely feminine white female (Pam), they are straight common boring average fairly intelligent young people in their 20s, much like a modern version of co-eds in a wholesome but dull 1940s college life B-picture. They are average Joe + average Jill: calmer, smarter, nicer and much better looking than the others in the office. Even though they have no particular skills or interests or even personalities of their own, they find themselves surrounded, seemingly until the end of time, by rejects and without any option to better themselves. What level of hell are they supposed to inhabit?

By means of the Jim/Pam character ideal, the god-like writers establish their Adam and Eve condemned to live outside the Garden. But to what end? These near homonym plain-named milquetoasts are intended as model citizens with whom the audience is supposed to identify, the “good guys,” presumably just like them. Presumably, the audience of millennials with sufficient disposable income to buy the advertisers’ merch is supposed to love these two trapped in ambergris, to root for them that they might fall in love, make some kind of success, but, whatever they do, to get the hell out! But they never do, really, and never will, because the writers condemn them, too.

The director strengthens this foundational communication between the virginal pair of innocents and the audience by constantly breaking the proverbial fourth wall: Jim and Pam often directly address the camera. They do so to garner agreement and sympathy from the audience: you see (wink wink) how terrible everyone else is? You and I, hint hint, we are the Normals. We are trapped among the losers, but we are better than that. Or so you might think. But the show’s creators have cynically manipulated the American love of the underdog into an identification which actually insults the viewer.

It should be clear to you by now that the writers of this dreadful show lack compassion for their own fictional creations. Do they even understand what compassion is? A writer creates a character when an idea is sufficiently important to necessitate its creation. Characters represent core ideas in a writer’s consciousness. The core idea in this show is utter disdain. Their real target is not the fictional character: It is the audience.

The writers deliver their message of toxic misanthropic irony to an audience they posit is as resentful and cynical as they are. They would have you profess by your laughter that you, too, are mired in Loserville with the losers and that you, too, are superior to them. (Well, are you?) But, is it not reasonable to infer that only losers would stay with losers? So Jim/Pam, with whom you are intended to identify, are losers, too. So, you who watches and laughs is a loser, too. Every character on the show who comes through the Scranton office is a loser; and so are all of you in the audience. The only winners are, of course, the better-dressed, very adult, ultra-competent bigwigs from the Manhattan corporate office and thus, by extension, the show’s creators and the network executives. This is the core idea the motivates the entire show.

Do you see now how they hate you? Do you understand how the show’s creators have set you up and trapped you into thinking so badly of yourself and your fellow Scrantonites (and by extension your fellow Americans) that you are willing, even eager to vent your resentment with derisive laughter at the lower forms of life who sit at the next desk to you? Do you see how you have thereby agreed to condemn yourself as well?

Comedy does not perform this negative function. Comedy, which The Office is not, is joyous, mirthful, hopeful, loving. Comedy is not resentful, cynical, derisive and insulting. The Office denigrates the audience; comedy uplifts it. Let us compare and contrast The Office with the work of Laurel and Hardy, about as representative of comedy as any act ever was.

Laurel and Hardy have been beloved by audiences the world over for a century. Why? What is to recommend them as characters? Stanley is dumb; Oliver is silly. Stanley is too thin; Oliver is too fat. Neither is a cad, but neither is an angel either, for Stanley lets the cat out of the bag once too often to Oliver’s detriment and Oliver never quite learns that his bragadoccio leads Stanley into many of the fine messes Oliver claims Stanley gets him into.

As busking musicians in You’re Darn Tootin’, they have no money and no prospects and end up with neither. They are only rarely employed, and when hired usually as woodworkers or day laborers perform poorly, making great guffawing gaffes, as in The Music Box when the piano case hurtles down the enormous flight of stairs they are supposed to carry up. They never really succeed with the ladies and when Ollie does, as in Thicker Than Water, he is inevitably henpecked by a woman half his size. They never achieve much of anything in life.

And yet, in spite of the pratfalls into trap door openings, the smashed plates over the head, the soakings in watery canals, the pulley-hoistings by mule into barnlofts, etc., when were they ever truly made unhappy? Never. They always make it past every obstacle in faithful friendship to one another, together. Whatever they have, they share and share alike. Trouble never lasts long for this positive, life-affirming duo, as they go through life together, imperfect as they are and over their heads without a life-boat in sight.

They break the fourth wall as do Jim/Pam and for similar purposes, as if to ask “see what I have to deal with?” And we may be entirely sympathetic and laugh, but we are never laughing at them. We laugh at the circumstances they get into. We love them. And they are so delightful, even though we may chortle, “Oh, they are so dumb!” who wouldn’t want Laurel and Hardy to love them? That is because we love them in spite of themselves and by loving them, whom we recognize to be much like us in so many ways, we are actually loving ourselves. That is the purpose of comedy: to inspire a joyous love of our life in spite of it and to share it with those we love. Irony and resentful cynicism is toxic to the soul. Comedy and loving laughter is what we need.

Real comedy compassionates. There is a reason why the Greek tragic trilogies ended with a satyr play.

It was a blessing on the audience to forgive itself for its inevitable imperfection as human beings. What passes for comedy today is ridicule engendered by judgment. Judgment is a very unchristian idea; you do not know how stupid and hopeless you are, so we must come in and eliminate you in order to save you. Then, once we have taken over, we can make the world a perfect place where all who think like and submit to us will live in perfect harmony, under our totality of control, of course.

Read more in New English Review:

• The Spike in Global Anti-Semitism

• Continuing Corruption in Equatorial Guinea

• Michel Houellebecq’s Seratonin: A Novel

Charles Dickens was perhaps the most compassionate writer a fictional character ever had. When he writes of the divine mercy granted even unto his fictional characters, we are witness, in fact, to his own mercy-granting nature:

In the exhaustless catalogue of Heaven’s mercies to mankind, the power we have of finding some germs of comfort in the hardest trials must ever occupy the foremost place; not only because it supports and upholds us when we most require to be sustained, but because in this source of consolation there is something, we have reason to believe, of the divine spirit; something of that goodness which detects amidst our own evil doings, a redeeming quality; something which, even in our fallen nature, we possess in common with the angels; which had its being in the old time when they trod the earth, and lingers on it yet, in pity. (Barnaby Rudge, Chapter 47, opening paragraph)

Unlike Dickens, the writers of The Office do not possess the capacity for mercy because they are without pity. Indeed, there is no love whatsoever in modern “comedy,” of which The Office is a stellar examplar. It isn’t comedy: It is “contempt”edy.

Obviously, there may be people who carp that older comic modes were rich with ridicule, but this was employed to point out imperfection: Think Tartuffe. Ridicule was employed in the service of spiritual instruction. Forgiveness is the heart of comedy; that is the beating heart of happy endings.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

_________________________

Richard Kuslan is an admirer of Donne, Sheridan, Byron, LeFanu, Trollope, Orwell, Sacheverell Sitwell, Christopher Logue and Jean Sprackland, among (many) others in the English language. He marvels at meaning’s fecundity when language is constrained by form and delights in the melodies that take to the air when the beautiful is read aloud.

Follow NER on Twitter