The Non-Extraneous Essential Spare

by Boris Starling (February 2023)

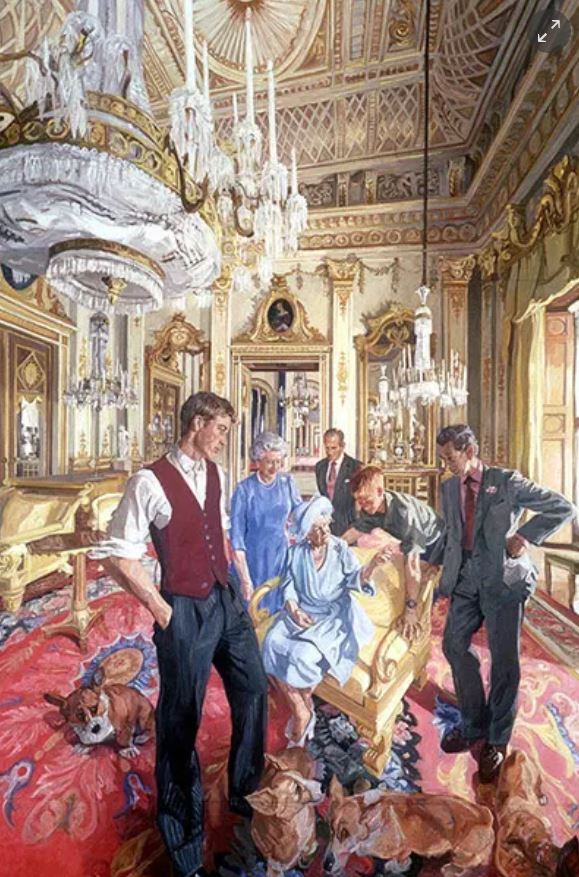

The Royal Family: A Centenary Portrait, John Wonnacott, 2000

Forget the extracts, the leaks, the furor and all the noises off. At heart, ‘Spare’ is the story of a deeply damaged, lonely and lost man: a proper, revealing psychological study. The narrative begins with Harry aged 12 being told of his mother’s death, and to all intents and purposes that voice remains constant for the next 400 pages: that here, now, is a 38-year-old still trapped at that moment of pre-teenage trauma. (A therapist actually says as much to him about three-quarters of the way through). That 12-year-old voice is vulnerable, confused, questioning, searching and contradictory: at Diana’s funeral he speaks of ‘keeping a fraction of Willy always in the corner of my vision’ so as to have the solidarity of fraternal strength, and in the days and weeks afterwards he tries to somehow convince himself that Diana has faked her death and will one day reappear for him and William.

Forget the extracts, the leaks, the furor and all the noises off. At heart, ‘Spare’ is the story of a deeply damaged, lonely and lost man: a proper, revealing psychological study. The narrative begins with Harry aged 12 being told of his mother’s death, and to all intents and purposes that voice remains constant for the next 400 pages: that here, now, is a 38-year-old still trapped at that moment of pre-teenage trauma. (A therapist actually says as much to him about three-quarters of the way through). That 12-year-old voice is vulnerable, confused, questioning, searching and contradictory: at Diana’s funeral he speaks of ‘keeping a fraction of Willy always in the corner of my vision’ so as to have the solidarity of fraternal strength, and in the days and weeks afterwards he tries to somehow convince himself that Diana has faked her death and will one day reappear for him and William.

This trauma and his failure to process it is at the heart of everything he is and does, and to his credit he doesn’t duck the obvious inference that at some level he doesn’t process it because he doesn’t want to: that there is comfort and familiarity in fighting the same battle again and again no matter how painful, and that if he does work through the pain that might somehow fade his memory of her. He never says as much, but it’s clear he sees himself as the true keeper of Diana’s flame: because William will one day become his father (at least constitutionally), Harry must always hold onto their mother.

This constant idealisation of her, a young beautiful mother forever held that way for a boy just starting out on adolescence, is of course unrealistic, and finds repeated and obvious echoes in his treatment of Meghan. ‘She’s perfect, she’s perfect, she’s perfect,’ he says of Meghan at one stage, and though on one level this is common or garden infatuation and limerence which we all experience at the start of relationships, the constant spectral maternal presence (he silently thanks Diana when they learn that Meghan is pregnant with Archie) also makes it something darker and more unsettling.

The fact that he’s still at heart a child was of course what made him so popular for a while: the cheeky chappie who wasn’t a stuffed shirt like the rest of them, who knew how to have fun and yet also had that indefinable stardust warmth. But it’s also exasperating to witness a grown man now nearly 40 still seeing things in such a childlike and binary way—good and bad, fair and unfair, right and wrong—without any real appreciation of nuance or complexity. He repeatedly fails to acknowledge the many blessings of his life: at one stage he rails against the unfairness of the universe when at a friend’s wedding he finds himself still single, and when Tyler Perry lends them his mansion plus security force there’s no acknowledgement as to how rarefied this kind of thing is.

He’s also naïve to a fault, likening Charles’ statement that the royal family can’t control the media to Charles being unable to control his valet, as though this were some sort of Pyongyang P. G. Wodehouse rather than 21st-century Britain. Tom Bradby quoted the Serenity Prayer to Harry during his ITV interview, but of the three qualities mentioned there Harry has only one, courage (and he *does* have courage, not just physically but holistically too: it’s brave to walk away from an entire family and system, no matter what else you think it might be.) He doesn’t have the serenity yet to accept that there are battles he can’t win, and he doesn’t have the wisdom to work around the courtiers and the system, to get what he wants by being smarter.

As the title implies, this is a book all about identity, and here again the forever child comes to the fore. He talks of identity being a hierarchy, a succession of different mantles as you pass through life, and with each one you get further away from the child, the pure true one. So when Harry asks himself maybe the most universal question of all— ‘who am I?’ —he comes back to that child, the spare (‘there was no judgement about it, but also no ambiguity’) who is ‘so unscholarly, so limited, so distracted.’ He’s all too painfully aware of his limitations in this regard: he knows—and hates—that his effect on people is down to title rather than talent. Even what can seem petty things to the outsider are refracted through this lens: when seeking permission to keep his beard for his wedding, he wonders whether he wears one as a Jungian mask or a Freudian security blanket.

It’s revealing that the type of man he speaks most highly of, men like his former private secretaries Jamie Lowther-Pinkerton and Ed Lane Fox, are fantasy big brothers: alpha enough to have had decorated military careers, but also smart operators and sensitive diplomats. Here, as so often, he seems to be looking for people to fill a loss: ‘knowing by instinct who you were, which was forever a by-product of who you weren’t.’ But by the same token I thought of something I’d come across when writing about his Invictus Games in the 2017 book Unconquerable: The Invictus Spirit, about the competitors wanting to be judged by their abilities not their disabilities, and thought how much happier he might be if he applied the same line of thinking to his own life.

Harry has spoken of trying to separate the royal family from the Royal Family, and to seek rapprochement with the former even if the latter is impossible. But the two are the same: family is institution, institution is family. That’s the whole point, and that’s the source of so much of the angst and rivalry. The parts about the jostling for position between the various households is revealing if unsurprising: carving up charity areas, competing for airtime and photo opportunities, maximising the counts of royal engagements, forever not wanting to be outshone by another couple be it sibling to sibling or parent to child. Some of this is hilariously petty—Kate can open a tennis club but not wield a racquet there, because that would be tomorrow’s front page pic—but it also brings to mind one of the arguments for republicanism, that it would do the members of at least one family a service by releasing them from such ludicrous routines.

I’ve rarely, if ever, read such evocative and visceral accounts of what it’s like to be constantly hounded by paparazzi. It felt exactly the same as reading about victims of stalking: not just the actual presence of someone unwanted in your face, but the constant anticipation, the hyper-vigilance, the denial of safe space both metaphorical and literal. You might think it comes with the territory of being famous. I don’t agree: certainly no-one deserves it to such a relentless degree, especially not for pictures which are almost always of fleeting news value anyway. I felt genuinely angry during these bits, not just for him but for anyone who’s been through similar.

It’s a memoir, and like all memoirs it’s subjective rather than objective. I found most of it convincing, particularly the episodes in which he expresses psychological rawness or vulnerability (the descriptions of panic attacks and stage fright are very well done, for example.) When it comes to conversations with members of his family I dare say that, to borrow a phrase, ‘some recollections may vary,’ but that’s not to say their versions would be any less inaccurate in different ways: memory is biased, self-serving and selective no matter who you are.

But when Harry says ‘things like chronology and cause-and-effect are often just fables we tell ourselves about the past,’ that’s simply not right: chronology is not a fable. And there were several occasions when things didn’t ring true. He says that the deployment of rooftop snipers during their wedding was ‘unusual but necessary due to the unprecedented number of threats.’ But he, both as a royal and former soldier, must know that rooftop snipers are entirely standard at large events involving senior royals and/or politicians. He casually mentions that two of the soldiers with him on a resistance to interrogation course ‘went mad,’ which seems an extraordinary thing to drop in without further explanation. Who were they? What happened to them? Isn’t even mentioning this a violation of the Official Secrets Act?

The most egregious by far, however, is this: when discussing calling a fellow soldier ‘our Paki friend,’ he says: ‘I didn’t know that ‘Paki’ was a slur. If I thought anything about this word at all, I thought it was like Aussie. Harmless.’ This is bullshit. I was at the same school as him, 16 years beforehand. Eton is two miles from Slough, which has a large Asian population. The word ‘Paki’ was used a lot at school, usually about residents of Slough and shot through with racism, snobbery and disdain. It wasn’t used every day and it wasn’t used by every boy, but everyone knew what they were doing if they did use it. The idea that, nearly a whole more enlightened generation later, this particular word would have been downgraded to ‘harmless’ beggars belief and flies in the face of everything we know about social progress and prejudicial attitudes. Just to be sure, I checked with someone who was there at the same time as Harry. He was adamant that nothing had changed since my day, and that ‘100%’ everyone knew that ‘Paki’ was a racist term.

One of the recurring themes in the book, revealingly, is distance and space. Harry talks a lot of distance between people: how protocol and her own reserve dissuade him from hugging his own grandmother even when he wants to, how his father writes him sweet notes expressing the love and pride which he can’t bring himself to express face to face. Even when Harry phones Charles from Afghanistan, Charles urges him to write instead and says how much he loves receiving letters. But by the same token Harry never seems more at home than when in vast landscapes, far vaster than even the wilds of Scotland: Australian sheep stations, the African bush, and of course Afghanistan itself.

One of the best and most poetic sections is during his first tour there, when he’s doing a night shift as forward air controller: him alone on the ground talking to pilots of different nationalities as they criss-cross the airspace above and he talks them through mission conditions and progress. To them he’s just a voice and a callsign—Widow Six Seven—but to him it’s connection with other people on an invisible net arcing high into a desert blackness, and it’s really something.

There’s a reason that J. R. Moehringer is such a sought-after ghostwriter, and every page of this book shows why. His control of pace is masterly, and he captures Harry’s voice well: rather West Coast, but that’s how Harry speaks these days. There was the odd moment when a little more sardonic British humour wouldn’t have gone amiss, but no more than that. And he has a great eye for little details and descriptions: how large fierce alpha-male colour sergeants always have the tiniest dogs, how the Okavango delta in flood looks from space ‘like the chambers of a heart filling with blood’ and how, with the profusion of animals there during the wet season, ‘imagine if the Ark suddenly appeared. Then capsized.’

Both Harry’s father and grandfather repeatedly emphasise to him the value of work: to get on and get things done, for the benefit to self and to others alike. To British eyes at least, the charity foundation and podcast stuff seems rather amorphous, and a Netflix series and book together appear borderline solipsistic. To refer to Invictus again, one of the best things any royal has done in recent years: that was proper work, building a movement from scratch, being there every day, getting down and dirty with men and women he understood and for whom the games had visible and concrete effects. The games continue—Dusseldorf this year, Vancouver in 2025—but another similarly all-consuming project would, you feel, do him the world of good.

Opinions about this book have been split between those who think he should be banged up in the Tower forever and those who defend and welcome his speaking up and out against his family. We see reflected so many things which are important to people but on which they disagree: the lines between individual and collective, rights and responsibilities, dissent and discretion. Of one of his army instructors, Harry writes ‘he knew a secret about truth that many people are unwilling to accept: it’s usually painful.’ This whole thing has certainly been painful not just for him but those around him too: one must hope that for all of them, somehow, it will eventually end up having been worth it.

Table of Contents

Boris Starling is a British novelist, screenwriter and newspaper columnist. His first book, Messiah, was on the NYT and UK bestseller lists and, in 2001, was made into a BBC miniseries.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast