The Pandemic of Authoritarianism

by Theodore Dalrymple (May 2020)

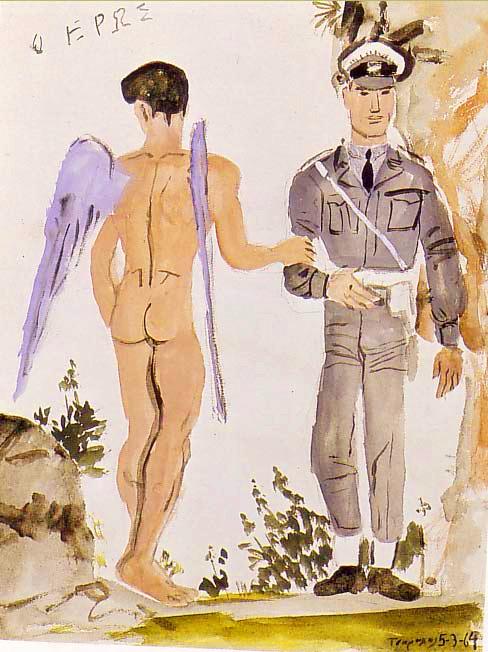

Policeman Arresting the Spirit, Yiannis Tsaroychis, 1964

One of the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic has been to call forth in the media of mass communication industrial quantities of what one might call the higher cliché. (A little-remarked on advantage of the epidemic was that, when you telephoned people, you could be more or less sure that they would be in.) No doubt because of social distancing and confinement, and for lack of anything else to write about, every scribbler soon turned philosopher, philosophy being the last resort of the hack with a deadline and nothing to say. When nothing happens, there are always abstractions to fall back on.

Abstractions and the future: what will the effect of the pandemic be on the world economy, human history, etc.? Will it have changed our psychology for ever, whether for better or worse? Will it have increased our belief in a deity, or will it have been the icing on the cake of atheism? What writer can resist the lure of the unanswerable, the opportunity to write what cannot be proved wrong until no one remembers what he has written or cares any longer?

Despite the fact that no one foresaw the pandemic or its effects, people still had some faith in the art or science (or whatever it is) of prognostication. There have, of course, been a considerable number of works of science fiction foreseeing the emergence of a deadly bacterium or virus that threatened Mankind with extinction, but Covid-19 never remotely threatened to do so, and in any case a vague imagined futurity is of as much use as a prediction as that at some time in the future the stock market will go up or down. For a prediction to be any use, it has to be a good deal more specific as to timing, otherwise it serves only to increase anxiety. From the point of view of utility, one might as well examine chicken entrails.

But speculations as to the future are like metaphysics, we are so constituted as conscious beings that we cannot do without them. And perhaps we should divide prognostications into lessons and effects, the two being related but not identical. There can be lessons without effects and effects without lessons. It has to be remembered also that there is no historical experience from which the wrong conclusions cannot be drawn.

Did the epidemic reveal anything about our condition or situation that we did not know before or could not have known if we had thought about it? It is so obvious that it amounts to a cliché that not only life itself, but the economy as we have constructed, hangs by a thread: and yet the speed with which so much unravelled came as a surprise. Untune that string, said Shakespeare in a different context (he was speaking of social hierarchy, whereas we are talking of supply chains and economic interdependence), and hark what discord follows! Yet, if we had stopped to think of it, we might have realised how unwise it was, strategically, to outsource the production of almost everything to distant and not necessarily benevolently-disposed foreign powers.

And yet our own habits—namely, spending more than we earned for years and years, indeed for decades—required precisely this. In order to maintain the illusion of solvency, money had to be created and interest rates kept low; but to avoid the appearance, though not the reality, of inflation, prices (except for property and financial assets) had to be kept low. The only way to do this was to outsource the manufacture of goods to low-cost economies, and voilà! with the able assistance of the coronavirus, the economic situation developed that we are in today.

The problem with human life, of course, is that we are perpetually starting out from where we are rather from where we ought to have been if we had been wiser than we actually were. We are constantly having to do the best we can in the circumstances, though we usually make a mess of it: and thus the whole infernal—but interesting—cycle starts up again.

As for lessons, they are no sooner learned than (usually) forgotten—unless they be the wrong ones, which are usually the most enduring. Another problem with lessons is that no one can agree what the correct ones actually were or are. What were and are the lessons, for example, of the First World War? That multinational empires are rotten, that nation states are invariably expansionist, that he who wants peace must prepare for war, that only a thoroughgoing pacifism can preserve the world from cataclysm? History does not teach lessons as if it were an old-fashioned schoolmistress in a primary school who brooks no contradiction from her pupils.

Furthermore, there are different levels at which lessons may be taught, the individual, the collective and the political. At the individual level, one is apt to learn when shortages arise that most of the things of which one goes short were not necessary to one’s happiness in the first place; and this in turn suggests that materialism, in the sense that the good life is and ought to be the ever-greater consumption of material goods, whether they be refined food or sophisticated electronics, is false, and that, as a consequence, we have most of us long run after false gods.

This lesson notwithstanding, as soon as normal service is restored in the form of an endless supply and huge choice of material goods, we revert to our former materialism. We were not insincere in our former belief that consumption of material goods is not all-important or necessary to human happiness, any more than the person who diets is insincere in his desire to lose weight but puts weight on again as soon as he stops the diet. It is simply that the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak. The epidemic might have taught something, I suppose, but just because something has been taught does not mean that it has been learned.

As for the collective or political lessons of the epidemic, I fear them more than rejoice in them. They seem to me likely to reinforce a tendency to authoritarianism, and to embolden bureaucrats with totalitarian leanings. One of the surprising things (or perhaps I should say the things that surprised me) was how meekly the population accepted regulations so drastic that they might have made Stalin envious, all on the say-so of technocrats whose opinions were not completely unopposed by those of other technocrats. There was, as far as I can tell, no popular demand for the evidence that supposedly justified the severe limitations on freedom that were imposed on the population. I suppose an encouraging interpretation of this readiness of the population to do as it was told is that it demonstrated that, all the froth and foam of opposition to political leaders notwithstanding, fundamentally the authorities were trusted by the population to do the right thing. Much as we lament, therefore, the intellectual and moral level of our political class, there are limits to how much we despise it. In other words, we believe that our institutions still work even when guided or controlled by nullities.

A less optimistic interpretation, as usual, is possible. Our population is now so used to being administered, supposedly for its own good, under a regime of bread and circuses, that it is no longer capable of independent thought or action. We have become what Tocqueville thought the Americans would become under their democratic regime, namely a herd of docile animals. Only at the margins—for example, the drug-dealers of banlieues of Paris—would the refractory actually rebel against the regulations, and that not for intellectual reasons or in the name of freedom, but because they wanted to carry on their business as usual. (I should perhaps mention here that I number myself among the sheep.)

In Britain, at any rate, the epidemic revealed how quickly the police could be transformed from a civilian force that protects the population as it goes about its business into a semi-militarised army of quasi-occupation. This transformation is not entirely new, alas; it has been a long time since the policeman was the decent citizen’s friend. Under various pressures, not the least of them emanating from intellectuals, he has become instead a bullying but ineffectual keeper of discipline, whom only the law-abiding truly fear.

I first sensed this development many years ago this when a traffic policeman asked to see my licence. ‘Well, Theodore . . . ’ he started, calling me by my first name when a few years before he would have called me ‘Sir.’ This change was significant. I had gone from being his superior, as a member of the public in whose name he exercised his authority, to being a kind of minor, whom it was his transcendent right to call to order. He was now the boss, and I was now the underling.

The change in uniform, too, has worked in the same direction. Traditionally, since the time of Sir Robert Peel, the uniform of the British policeman was unthreatening, deliberately so, his authority moral rather than physical. Now, he is festooned with the apparatus of repression, if not of oppression, though in effect he represses very little of what ought to be repressed in case it fights back. The modern police intimidate only those who do not need deterring; those who do need it know that they have nothing much to fear from these whited sepulchres, these empty vessels. Incidentally, the French police have undergone a similar deterioration in appearance: gone is the reassuring képi in favour of the moron’s baseball cap, and some of them now dress in jeans with a black shirt with the word POLICE across its back, which is not difficult to imitate and makes it impossible to know whether a policeman really is a policeman or a lout in disguise.

The Covid-19 epidemic has come as a great boon to the British police. Increasingly criticised for their concentration on pseudo-crimes such as hate speech at the expense of neglecting real crimes such as assault and burglary, to say nothing of organised sexual abuse of young girls by gangs of men of Pakistani origin, they could now bully the population to their heart’s content and imagine that in doing so they were performing a valuable public service, preserving the law and public health at the same time. Thus they transformed their previous moral and physical cowardice into a virtue.

Of course, in bullying the average citizen who was very unlikely to retaliate they took no risks, unlike with genuine wrongdoers and law-breakers, who tend to be dangerous; but the fact remains that most individual policemen joined the force motivated by some kind of idealism, a desire to do society some service, though they soon had these naïve fantasies knocked out of them by the morally corrupt or bankrupt leadership of the hierarchy which owes its ascendency to its willingness to comply with the latest nostrums of political correctness. The faint embers of the policeman’s initial idealism were no doubt rekindled by the opportunity to prevent the spread of the virus, as they supposed that they were doing, but some of them, at least, far exceeded even their flexible and vaguely-defined authority and began to inspect citizens’ shopping bags to determine whether they were hoarding goods that might be in short supply. This was a step too far, and at last there were protests; the police desisted.

Nevertheless, the epidemic revealed that, whatever our traditions, we are less proof against authoritarianism than we like to suppose; and that authority is rarely content to stay within the limits set down for it but is like an imperialist power that is always seeking the means of its own expansion. Moreover, public health, while real enough, can be turned into a Moloch capable of swallowing anything. There is, after all, no human activity that has no consequences for health, either individually or in the aggregate; and what, after all, is the public but an aggregate of individuals? Public health, we have learned, is the highest human good, the precondition of all other goods. A solicitous government therefore has the right—no, the duty—to interfere in our lives to make sure that we stay healthy. And authority once taken rarely retreats of its own accord.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest books are The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Kenneth Francis) and Grief and Other Stories from New English Review Press.

NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast<