The Stain

by David Platzer (August 2021)

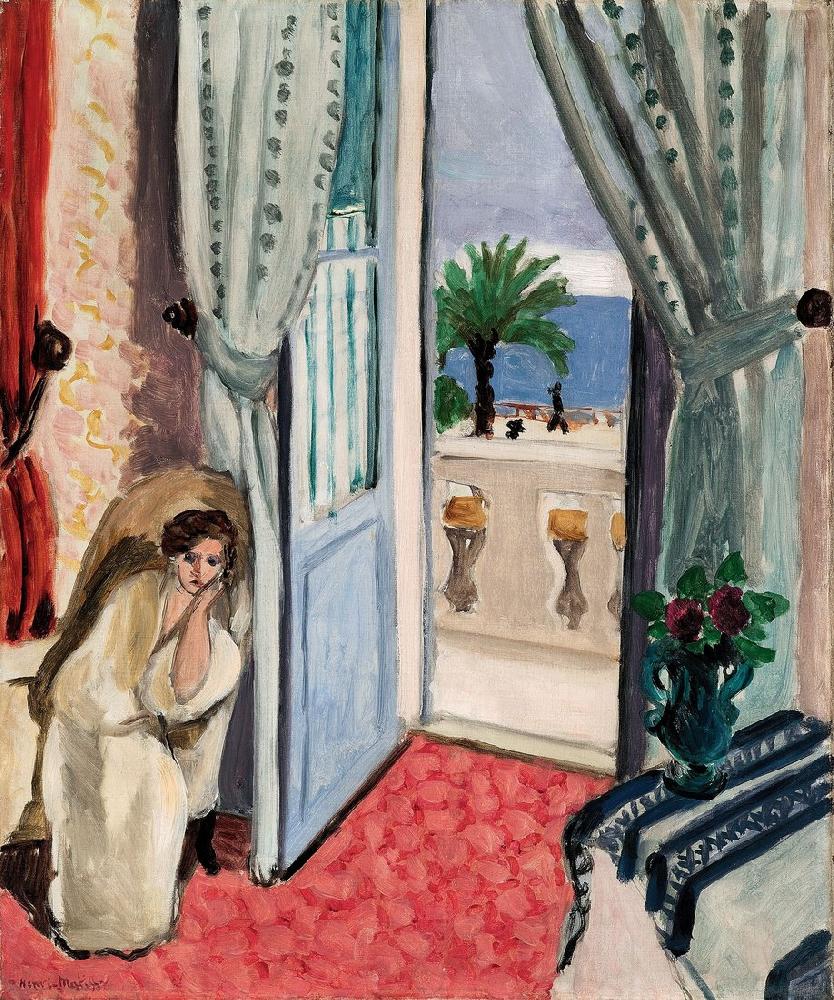

Interior at Nice, Henri Matisse, 1919

“Aie!” Donald said. He hadn’t counted on there being grease stains on the bottom of his guitar bag when he absent-mindedly hoisted it onto the side of his wife’s most prized possession, her beige sofa, in preparation for slinging it onto his back and strapping it onto his shoulders.

It was exactly the kind of thing he did too often for the marriage’s comfort. There had been the time early in the marriage when he’d bumped into the flat board in the middle of Claire’s chest of drawers that she always kept open. The collision had been hard enough to break the chest. The clumsy unintentional accident, was a crime, even if only by neglect rather than intent. Someone had worked on that chest of drawers with a craftsman’s patient love. It was not for Donald to destroy it. Objects like these were precious to Claire. They gave her comfort in an uncertain world and she loved them for their beauty. She liked to have her abode comfortably ordered. The documents she used for her work, the files of material for her visits to monuments and neighbourhoods all over the Paris region were neatly filed and arranged. She wanted everything in her life to be that way.

Donald introduced the element of chaos into her tidy existence. He bumped into furniture. He spilled things, usually on himself but sometimes on the table or the floor. Though he tried tucking his shirttails in they had a way of coming out against his wishes. He brushed his curly hair but it still wouldn’t stay in place even when he put hair dressing on it. Loveable though he could be, he was a walking disaster area.

Claire had been in a good mood when she left that morning. Such days were less usual than anyone knowing her smiling, charming ways outside her household would have imagined. Her good moods, once frequent as tulips in April, were now rare as roses in January. They had been married five years and now Claire was talking of separation. “I’m losing patience and when I’m disagreeable, I can be very disagreeable,” she told him at the time. It was hard for anyone who’d never seen her in a bad mood to imagine Claire disagreeable. She smiled easily and she had a real sweetness and a genuine humanity. She talked to homeless people on the street, she was roused to rage when she heard ignorant attacks on immigrants. “Immigrants are the real heroes of the age,” she said. “They leave their lands and what they know to come to countries where they’re made scapegoats while they do the real drudge work that the locals won’t touch.” She hated injustice and brutality. But her sense of how things and people ought to be could make her intolerant of anything falling below her high expectations of what people and life ought to be.

Everyone who knew them found them a handsome couple, Donald with his curly hair and sensitive features, like a Keats survived into middle age, and Claire with her long blonde hair, green eyes so full of life and warmth, her perfect dress sense, her natural elegance. Donald was thin and taller than the average, Claire moved with the grace of the dancer she once was before she turned to art history. They were both passionate about books and art. Claire was a tireless worker who made her guiding tours to Paris monuments and art exhibitions seem natural, spontaneous, and easy, belying all the hours of preparation she put into them.

In the early days of their relationship, Donald seemed to her an ideal. Claire couldn’t be involved with anyone, even as a casual friend, unless she felt admiration. She knew enough English to be able to read Donald’s writing and she thought it was very good. “You were born to write,” she told him. When editors returned his work with polite letters, explicit only in their refusals, she told him “my bichon is the best, the editor just doesn’t understand.” She was exactly the companion that any aspiring artist needs, endlessly supportive and believing in a talent that the world at large had yet to discover. They lived in a nice three-roomed flat in the eleventh arrondissement near the Place de la Nation.

Those first few years Donald had a good life. Except for giving private English lessons, he was a virtual househusband. “Peace begins for you,” Claire would say in her bright clear voice when she left in the morning. She would plant two kisses, one for each cheek, on him, before going. When she didn’t have an assignment, she stayed at home, working on her tours, patiently polishing her talks until they were marvels of thoroughness and clarity. Their living room was divided into two studies. She sat at her desk in her section, her art books on the shelves she built and designed all around her. Claire loved decoration, her nest was vital to her. His area was across the room. His books he had accumulated himself. The shelves she had bought for him at the BHV department store, Paris’s most popular emporium, and put together herself, painting them a light blue that went with the wallpaper. Everything had to match in the apartment, every shade had to blend with the others in a perfect harmony. His desk, a beautiful wooden antique one, she found at an antique shop near her old neighbourhood in Montmartre. Eventually she found an armchair to go with it. It was damaged when she bought it so she found a good craftsman to repair it. Donald was as helpless as a baby when it came to doing anything around the house.

Claire liked to stay at home and work. “I’m a bear,” she said, using the French term for anyone antisocial. It wasn’t quite true. She could spend hours on the telephone with one of her friends and her lovely smile and seeming openness made her loved. During their few years of happiness, she was the light of Donald’s life and he took her too much for granted. She would throw her arms around him, kiss the back of his neck, and say, “I’m glad to have a Donald in my life.” Donald, who had been alone before, forgot easily how lucky he was, not realizing that this life together might just be an interlude of light in the span of darkness. Sometimes he saw other women and wished he was free for flirtation but he liked his life with Claire and didn’t want to lose it.

After a few years, things began to go wrong. Claire had always wanted to have a child. “It’s what I feel I was born for,” she told Donald when she became pregnant. Paternity terrified Donald. He didn’t want the responsibility. They had a nice simple life together with outings to the cinema or to museums several times a week and four or five trips a year. A child would complicate all that. “I’m sure you would fall in love with the child once we had it,” Claire told him. It was her destiny she was pleading for. She was trying to help him accomplish his, though so far its only manifestation was in a few articles accepted and published and pages of manuscripts either rejected or abandoned. The blood tests done on them before the marriage showed their blood types incompatible. Claire’s doctor should have given her a shot to adjust this. He didn’t. Two days after Claire went to a group meeting at the hospital for expectant mothers, she began to bleed. She called her gynaecologist. He told her to stay in bed. The bleeding continued. Two days later, he told her to go to the hospital.

Donald waited at home, working on a text that he was to give to a group in place of Claire the following Monday. The subject was Amsterdam, the city they had spent their honeymoon in. Donald had known it before Claire. He proposed the city to her and she absorbed it. Claire was always open to new places, beauty in all its forms, new habits of eating. She incorporated Amsterdam into her repertoire, organized trips there and Donald wrote the historical background texts for her brochures. He knew enough about the subject to replace her at her lecture on Monday since, whatever happened to the baby, she would be too weak to appear.

Early in the evening, the phone rang. Claire was crying. “His little heart stopped beating,” she said between tears. “Can you come and take me home?”

Donald, who hadn’t wanted the baby, felt the world breaking around him. It was the end of October, the little light there had been in the day was gone. It was dark outside. Night had fallen. Night covered the earth. Outside street lamps were shining. The light they spread was false for the real light had gone. Maybe it would return tomorrow, maybe it would never really come back. Not in this life anyway. The mistakes one makes in life aren’t like those in manuscripts. One cannot go back and retype for life’s manuscript cannot be revised. There are no second takes. One has one cut to get it right and that is all. Donald felt guilty and wondered is his ambivalence had discouraged their poor child from living.

There was a long winding corridor of empty rooms. Donald went around it as if in a hurry to get to a bomb set to go off in minutes and defuse it. Not that he would have had the knowledge to do that.

Claire was in the room, wearing the golden sweater that matched her hair, jeans olive green. She liked bright colours. She was crying helplessly. Donald went up to her and held her in his arms. “I love you more than anything in this world,” he said. For once he spoke from the heart without premeditation.

A young doctor came in, his long white coat unbuttoned over his shirt, tie, and tan corduroys He was short and compact with thick dark hair.

“I want to have a child,” Claire said.

“Yes Madame,” the doctor said, “but you must remember you are over forty years old.” He spoke gently, softly, without the sarcastic indifference doctors so often show. The loss of a newly-formed child a woman is carrying within her is as much of a loss as that of an infant already come to term.

“I don’t want to live here anymore,” Claire said when they got back to the flat where they had lived for five happy years.

From then on, the strings were never quite in tune. “We should separate,” Claire told Donald the day before Christmas. “You never loved me and I never loved you.”

“I did love you,” Donald said. It cost him a lot of pride to say it. He remembered the way she was with him in those years when she threw her arms around him and seemed so radiant, when she said how glad she was “to have my Donald” and when she said she wanted them to die together when the time came. If that wasn’t love, what was? She had been so happy, so full of confidence in life. “I never worry about anything until it happens,” she said in those days.

Now she did worry. “What is going to happen if the Bureau closes and I haven’t my visits anymore?”

“There are plenty of other things you can do.”

“I’m used to doing this. I don’t feel up to starting all over again. I’m tired of working anyway.”

Donald tried writing a thriller. Thrillers could make money, even pedestrian ones. The racks were full of them, even ones by less-known authors. He couldn’t get involved in his thriller. Whenever he tried working on it, he fell asleep at the typewriter. It didn’t seem real to him. He couldn’t imagine it seeming real to anyone else. He just wanted to publish one book to show he could do it. He had sent out a novel the year before to various publishers. “Well done, but lacks that commercial punch so necessary to today’s fast-paced market,” was the response of Hilary Sneedham of Snipet and Ross, once an independent publisher now part of the Owl Group, itself a subsidiary of the Megalothilic International Company, which owned chains of supermarkets, arms manufacturers, the Cosmopolis Movie Company and various others.

Rather than trying to go on hawking the thriller, he put it on the back burner—he could trot it again when he had a success with something else—and got to work on a historical novel. The idea came to him in a dream. His sleeping mind saw a vision of a sixteenth-century Flemish seaport, a Bruges like town, a centre of commerce and also of art. He pleased himself with recreating this bejewelled setting—the story was almost secondary to him. He had always worried that he did not devote enough place in his writing to description. Description was the main element of this story, drawn from memory of paintings. He admired the intricate detail of Flemish art.

Claire loved the story. So did those of her colleagues who read English. They were glad to find in writing some of the qualities they loved in painting, prose that captured the green waters and evanescent skies of painting, its blue cloaks and scarlet tunics. Christian de Chateauterre, a highly distinguished biographer though he also wrote less celebrated works of fiction, told Donald he would have been proud to have written it.

Confidently, Donald sent the story around. It was returned every time. “We like it, but we’ve too much fiction already,” the editor of a literary magazine that had published an article of his replied. Donald guessed that had the editor liked it enough he would have made room for it even if he had too many fiction on his plate. Others just returned it. “Setting is brilliant but the encounter lacks the fire and violence of a sudden sexual encounter,” was one editorial comment. “I’m afraid the scenery brilliantly described, had more life than the characters,” was a third response. At least he knew he could write descriptions when he tried! Since so much so-so fiction got published, despite flaws and inadequacies, Donald began to wonder if there was some kind of curse on his.

Donald and Claire went regularly to the art houses in the Latin Quarter which showed classic movies. They saw almost all of Hitchcock’s films at the Champo, a Cary Grant festival at the Action Ecoles. Donald became enamoured of Carole Lombard on seeing To Be or Not to Be, Twentieth Century and My Man Godfrey at the Réflets Médicis. The fact that she died sixty years earlier in a wartime air-crash added a particular poignancy to this crush. A youthful ambition to become an actor resurfaced after Claire said she’d made a mistake to settle for a love anything less than Cary Grant’s for Deborah Kerr in An Affair to Remember. An experience of that kind might well have inspired Aldous Huxley to write a vaguely supercilious essay on “the effects of bad art.”

Talk of becoming an actor wasn’t going to regain Claire’s affection. “You’re born to write,” she said. “If you change direction now, halfway through your life, I’ll divorce you. You could go out and get a job working at a supermarket part time just so we can be assured of regular money. I’ve been paying all the bills myself for five years. It was my fault. I made the offer and you accepted it. Just like my mother, every decision I make is a mistake.” Donald felt the same way about his decisions.

He began carrying a pendulum. Before anything however trivial he thought of doing was vetted by the pendulum. He then suffered from a feeling that the pendulum might just be telling him what he wanted to hear. It told him he should resume playing the guitar and try to get work as an actor. As for writing, that was something he couldn’t help doing. Little fragments of poetry were always coming into his head even if he had trouble thinking up a story and spinning it to its end.

For Claire, it seemed that Donald’s wish to act had come from nowhere. She was wrong. All his life Donald had believed he was some kind of artist, even if hampered by contradictory doubts that he had no talent. In youth he had read Somerset Maugham’s stories, some of which like “The Alien Corn” showed the tragedy of a young man who confused a love for art with the ability to create it and wasted a life that might otherwise have been well-spent as a banker or insurance broker. As a child, he knew he would be an actor.

He went to acting school in London, His accent was already British though more Scottish than English, perhaps because his mother was from Scottish ancestry but also because he had studied so much Sean Connery’s performance as James Bond that the actor’s style had rubbed off on him. But that wasn’t good enough to satisfy the British authorities. They had strict rules against allowing Americans to work in their country, no matter how British they might be able to sound. Though he tried to get acting work in New York he felt out of place as well as hankering for Europe. When he went to castings in New York, he got told he seemed too European. “What about Cary Grant?” he asked one casting director. “He was funny,” she said.

Donald decided he’d work on writing and go to Europe. When he met Claire, he was living in a room in a large, gloomy Haussmannian apartment on the boulevard Saint-Michel. For several years, he was content to confine himself to writing, But once an actor, always an actor. His difficulties with Claire only increased his desire not only to act but also to sing in public, something he had loved doing in his teens. This disturbed Claire even more than his acting, She liked people to fit in boxes rather than leap out of their pigeonholes and reveal other sides to themselves. A friend in Paris gave him the addresses of several casting directors who picked extras on films. Donald was soon getting work of that kind. He also dusted off a guitar he had and began to going to Paris’s Place des Vosges to sing and play under the arcade. Singing the songs he had loved in his youth and feeling a basic distrust of the way the world had gone since 1973 was enough to let him let his hair grown long just as he had in his teens. This did nothing to assuage Claire’s growing worry about him. He did, however, felt satisfaction in playing in public and sometimes being rewarded with coins and even notes.

Excellent though all of that was, it didn’t solve his immediate dilemma. How was he going to get this stain out? He always had trouble getting stains off his clothes. There were products supposed to work in such situations. Trouble was they never seemed to get the stains off his clothes. Often they added other stains to the original.

First he tried water and soap. All that did was rub the stain further in, while adding a thick cloud of soapy dampness around the spot.

He went back and looked under the sink. There he found all kinds of household products.

“Please God, please, let there be something here that works!” He didn’t want another fight. There had been two already this week and it was only Tuesday. And that wasn’t including her frowns, the scorn that he sensed in her voice. He remembered how sweet she was and his heart crumbled like snow in sunlight.

Under the sink, amid the thick pipes, he found bottles of detergent, dishwashing liquid, wax for the floor, all kinds of useful things, but not what he needed. Then, in the back of the cupboard, he found a stain remover! Too often he used items without reading the instructions. This time he took the time to read the label. Often when he read the instructions, he was left afraid to use it for fear the chemicals would scald his hands or eyes. For a moment, he thought of going to start buying environmental-friendly household products at the ecological market Le Nouveau Robinson in Montreuil. He soon discarded the thought. There was no time to wait in this emergency. He could imagine how shattered Claire would be when she found a spot on her sofa. She looked nervous even when he sat on the thing as if it were a museum piece. Imagine how she would react when she found it damaged, however slightly. He could hear her shrieks.

Sprinkle it on, the label told him, but avoid rubbing it in. Good advice for critics! Donald smiled to himself. Then let it soak for a minimum of three hours, longer with tough stains. The maximum, in the case of something really tough to get out, was twenty-four hours. After that, rub it. Leave more time for tough stains.

The trouble was she would be home in three hours and he had to go out before then.

He needed to make some money. He asked his pendulum if today was a good day for singing with his guitar on the Place des Vosges. It swung in the positive clockwise direction that meant yes.

He still wanted to avoid angering Claire—pleasing her was well-nigh impossible. For that reason, he’d decided to look for a job. There were daily jobs he knew he could do well. He knew all about books, the commercial aspects excepted. He was sure he would be good at selling them. He could talk to people easily and persuade them to buy books he believed in. There was a book shop in the Marais run by a young American named Persephone. She had dark hair, raven eyes and porcelain-china skin. Donald would have been interested in her except that her husband, a pleasant fellow who taught at the American University, was often around. When Donald bought a book from her, she would give him a slight discount which made him feel he ought to buy more books from her. If he ever finished the novel he was writing and, through some miracle, it was accepted and published, she might even give a signing party for it as she often did for new books. Meanwhile he could use a part time job. His bank manager, Delphine, at the Crédit Lyonnais office, had left a message on his cell phone, telling him he was a hundred euros overdrawn. He had better replace it right away. The trouble was he had to buy groceries for Claire. That had been his responsibility from the start. Claire was not especially demanding but she expected at least a fresh salad and preferably chicken or fish if not steak or ham. He preferred to buy organic too since it was healthier. It might be a slither of a shade more expensive but medical treatment for cancer could be expensive, especially with the Social Security system more fragile than before. Claire disdained organic food which she considered a useless affectation.

He poured the product onto the stain. It came out in small sandy grains rather than liquid. That was maybe better. Liquid stain removers often left another stain even if they got out the original. He would just have to pray and hope for the best. Please God, oh dear God, make this work! Don’t let her see it!

It was a grey day with that crisp bite that lets you know winter is in the air. He went out and played for two hours on the Place des Vosges, earning a little more than ten euros. Not bad! Six of these were from an elderly-looking man with thinning short white hair combed in narrow strands across his pink age-freckled head. “I was listening to you across the park, Monsieur, and what I heard was so agreeable that I had to give you something.” Sometimes busking he had pleasant experiences like that which made him feel he was doing something worthwhile even if he hadn’t attained the fame he had dreamt of in younger days when everything seemed possible. The worth of a life was not measured in money earned but in the joy given others. Alain, who painted charming naïve views of the Place, expressed pleasure in seeing him. The painters who worked on the Place were all his friends. He liked Alain, a big bearded man with an easy-going naturalness about him that Donald found congenial. That afternoon, Alain sold two pictures to tourists. It was often that way. When the musicians had a good day, the painters did too.

His visit to Persephone’s shop, The Link on the Chain, was less successful. It was a charming little place on the rue des Tournelles, old-fashioned looking with books everywhere yet neatly arranged on the shelves. Persephone’s slender body was draped in a wool, vee-necked, ankle-length black gown, revealing her creamy upper chest down to the tops of her breasts. She slithered from behind her desk to meet him.

She smiled and took his hand lingeringly in hers. He looked in her eyes and felt how much he wanted to make love to her. Donald hated asking for a job. It put their relationship all wrong. She would never feel the same about him nor him about her. No one feels good refusing someone who asks for help, no one feels good about being refused even if a “no” is sometimes a hidden favour.

“We have two people working here already and that’s enough,” she said. The tone of her voice made it clear that she felt some resentment about being asked, “It isn’t easy taking on people here with all the paperwork to be done and the high charges. We haven’t got an overabundance of cash either. As a business, we’re surviving and perhaps a little more but some weeks are better than others and I can’t afford a third person. Once in a while, Sarah can’t come in or I can’t come in and we could use somebody to fill in. Leave your number and I’ll call you if I ever need you.”

After Donald left the shop, he stopped in the middle of the street, pulled out his pendulum, and asked it if he and Persephone would ever be lovers. It swung counterclockwise. He didn’t dare ask it if his marriage would survive.

There were Christmas decorations in the street, trees silhouetted in white, bright bulbs and bells hanging up and down poles. Every year Donald’s presents to Claire and hers to him became more modest. Last year she had given him a little book of Zen tales as if mock him for his recent interest in the counter-culture and he had presented her with a Vermeer calendar.

Going back to the twelfth, Donald asked his pendulum whether it was advisable to stop at the Crédit Lyonnais and see his bank manager. Thndulum spun rapidly clockwise.

Mademoiselle Delphine Meynard seemed to sprouting raindrops. Donald doubted she was more than twenty-two. To him, she looked closer to aged twelve. She had to be older than that: she would hardly have been allowed to work at that age, at least in France. Her brown hair was lank and thin like the rest of her. She looked like she had never seen the sun or been blessed with love or tenderness. Did she have a life outside of her job? What was it? Did she have a boyfriend? Did she live with her parents? Did they treat her kindly? Many people go through a period in late childhood and early adolescence when they look plain. Then suddenly they emerge from this chrysalis into beauty. Mademoiselle Meynard looked as if she was stuck in the chrysalis.

He had to wait outside a glass booth to see her. She indicated she was ready and he went through a series of doors. The first one he just walked through. He had to wait for a green light for the second to click open. He sat in the padded chair opposite her desk. She was nice. “Every time you are overdrawn, the bank fines you,” she said. It was kind of her to warn him. Her predecessors had just let him get into trouble.

“I haven’t got the money right now,” he said. “I’ll try to get some.” He would have to call home and ask his mother to send a thousand dollars directly to his bank account. It would take a few days. His mother always sent money when he asked her. The trouble was having to ask. It seemed a measure of his failure to earn a living from art. “I’ll get the money to you in a few days,” he said. “As soon as I can.”

“Try to get it here quick,” she said. She gave him a little smile and her tiny hand to shake. Donald tried to find beauty in her face. Her eyes, a mixture of green and brown, were nice. They looked like big round saucers. He told himself she was pretty after all, even though he knew she was merely plain. What needed was love.

Now it was a question of getting the metro back and hoping he got home before Claire so he could look at the progress of the stain remover, Oh please God, let it disappear! Please don’t let Claire see it! Not another fight!

It was already after five. That meant the 1 line would already be jammed with standing room only. City life! Pushing, shoving, jamming, surrounded by people, all of whom were strangers! Whenever he went to smaller, more manageable towns like Amsterdam. Whenever he went there, he felt relief. The water was everywhere and there were more bicycles than cars in the centre of town. You could walk just about everywhere without having to change subways or buses two or three times to go a short distance.

When he returned to his flat, the upper lock was unlocked. He squared his shoulders as he went in the door and took a deep breath. Breathing deeply was supposed to help but it didn’t. Perhaps he was doing it wrong. He seemed to do everything wrong in this life.

The light was on in the bedroom. Donald could hear Mozart. Claire liked to stretch out on the bed when she came home, reading Libération or a novel, playing music or opera on the little portable cd/cassette boom box they shared, sometimes watching the TV, letting the stress and strain of the day flow out of her. It was a hard life she had, taking her public on two tours a day. In her youth, in love with life, art and Paris, she relished the work. Now it wore on her.

“Hello,” she said, unsmiling. The greeting was sarcastic rather than warm but its relative neutrality indicated she hadn’t noticed the stain. Praise be to God!

Donald made himself a cup of tea. He had been making this with a mixture of hawthorn and black currant leaves since he learnt that he had high blood pressure. Sweetening it with eucalyptus honey, he sat down at the desk in the living room a few feet away from the sofa, turned on the computer he shared with Claire, and started work on his novel. He was diligent about his writing just as he was about his guitar-playing. So long as he wrote, he felt he was justifying his existence, even if he wasn’t earning much from it.

The product was still there, a tiny hill of grains working its wonders dissipating the stain. He took out his pendulum and he asked if the stain would soon disappear. It turned clockwise, indicating yes. All he had to do was get through the time needed without Claire seeing it. He didn’t dare ask the pendulum about that. He wished his relations with Claire were such that he could just tell her what had happened and have her accept it calmly, trusting patiently in his ability to resolve the problem. Four years ago, even three, it would have been like that.

The evening progressed. Every time Claire walked by the sofa, Donald’s heart beat faster. Fortunately, she walked straight ahead, not stopping to look at the armrest with its criminal evidence. It was like that Poe story in which the most invisible evidence is conspicuous. Hallelujah! God was being nice to him this time. Donald made dinner for them both as he almost always did. This time it was a shrimp curry. Claire adored curries and she was appreciative. “You are a good cook,” she said. His writing and his cooking were the only two aspects of him she still esteemed, as far as he could judge. They no longer kissed or made love. Donald couldn’t bring himself to practice the tender art with someone whose judgements he feared. He didn’t stop to ask himself if showing uxorious tenderness towards his wife might not have made a difference. If she had shown him the warmth formerly so apparent, he would have responded in kind. He never contemplated that it might be for him to initiate rather than just reply.

After supper, Claire asked Donald if he would wash the dishes. In the past the convention between them had been that whoever did the cooking was freed from the washing-up. Donald didn’t mind doing both. “No problem,” he answered when Claire told him she was tired and begged to be excused.

He held his breath again as she walked through the living room to the bedroom. There was no exclamation of anger or anguish. He let his breath out again with relief as he heard the sound of the television.

Donald sat on the sofa and read Proust while Claire watched her TV detective thrillers. He tried to do as much reading as he could not only for the pleasure it gave him but also to feed his writing. If only they could get through to tomorrow without her seeing the stain.

Claire’s TV show over, she went in the bathroom to change for bed. Donald tensed again as she walked through the living room. He had already brushed his teeth and changed into his blue cotton pyjamas. He got into his side of the bed, felt the comfortable covers around him, and resumed reading. As long as she just walked through the sitting room without looking at the sofa, he’d be all right.

He heard a gasp, followed by a shriek. He got out of bed and dashed into the next room. Claire in her pale blue bathrobe and pyjamas was standing over the sofa arm rest. Tears were gushing from her eyes like lava from a volcano. She stamped her feet up and down.

“What have you done, what have you done?” she shouted. “You monster, you brute! Why must you destroy everything you come near? I made the mistake of my life when I married you, I should have divorced you long ago.”

“I didn’t mean to, I’m sorry, it’s going to be all right, I put some stain remover on it, the bottle says it will be gone by tomorrow. It’s supposed to take a few hours, longer with touch stains.”

“You could have told me.”

He didn’t want to admit he was afraid. “It will be all right,” he said, hoping it would. The pendulum said it would but, like Thomas, he doubted.

She sat down in a wooden armchair she had bought for him a few years before and looked at him with the cutting eyes of a prosecutor. “It’s always going to be all right in your universe,” she said. “Everything goes wrong and yet somehow it is all going to be all right by the end of the play. The trouble is that nothing is yours, everything is somebody else’s. You can be optimistic because you have nothing invested. I worked two years to buy that sofa and with no help from you. You can go ahead and ruin it, just like you ruin everything else. You’re a typical vandal. Oh, I know, it’s an accident. Everything is an accident with you. When you broke my chest of drawers, it was an accident. You have a talent for writing, that’s true. You can’t get anything in focus. You can’t plan. You have to wait for a miracle to give even your writing what it needs. I have arrived at a stage of my life where I cannot wait for miracles and tolerate accidents. I want some peace and security in my life. I have worked since my teens and now I want to have a little dwelling which is all I can afford and some nice things to make me feel comfortable and happy. Maybe that is material. I don’t ask for much though.

“You, you cannot even allow me that. I know it is not your intention to destroy. You just cannot help it. I wonder where you think you are going. I worry about you, Donald. I am afraid for you. I worry that you are headed for a life of poverty and maybe even the streets. You are already on the streets with your guitar. You are happy if you earn a few euros. I don’t want to have to see you with no choice but the streets. I am not strong enough for that. You must handle it on your own. All I ask is that you leave me in peace with what I have left of a life. I have made all the wrong choices. Now I find myself left with no child, a career that may be about to disappear, no clear prospects. We had some good years together. Let us not tarnish their memory with quarrels and pleas. You can stay here until you find somewhere else but I want you to leave as quickly as possible. Don’t try to argue, don’t beg. I want no more discussion.”

“I put the product on and it says the stain will be gone by tomorrow,” Donald interjected.

“Please,” she said, “no more discussion.”

Argument would be like pounding at a door nailed shut. Donald found himself boiling with rage inside. He could feel blood welling up inside his head like water lapping against stone. He felt he was being treated unfairly, denied his voice. Why should she decide everything? He too hated argument. He was afraid of where the rage, once let out of the bottle, might go. He went into the kitchen and flapped his hands in the air, a gesture he had used since childhood, to express ineffectual emotion.

After a while he went back into the bedroom. Claire looked at him with scepticism.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I didn’t mean to do it.” Words, words, words! He realized how ineffectual they were in this and any other instance of real feeling.

In the morning the stain was gone, just as the product’s label said it would be. Donald waited for Claire to smile and curl herself against him, like a cat making up after a sulk. But nothing happened. She was waiting for something from him and him for something from her. Neither was forthcoming. As she went about, preparing herself for the day, Donald made up his mind. He had enough. It was time for himself to hit the road. He didn’t where he would go or what he would do. He had barely enough money to go and stay in an hotel. He hadn’t any friends close enough to ask them to put him up. He didn’t care. He would go out and found what he would.

When Claire came home that evening, the stain was gone. So was Donald.

__________________________________

David Platzer is a belated Twenties Dandy-Aesthete with a strong satirical turn, a disciple of Harold Acton and the Sitwells whose writing has appeared in the New Criterion, the British Art Journal, the Catholic Herald, Apollo, and more.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast