The Strange Death of Theo Van Gogh

by Robert Bruce (July 2017)

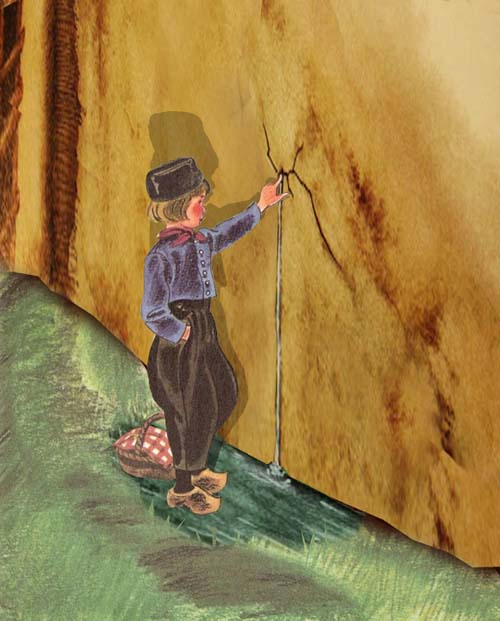

Little Dutch Boy safeguarding the essential. (Artwork built on the work of Marguerite Scott)

Prelude

Surveying the life’s work of Theo Van Gogh it is difficult not to read into it metaphors of civilisational decline. A distant relative of the great Artist, he had built his modest acclaim slumming the lowest reaches of 21st-century Prolefeed and, by his late thirties, he had exhausted even this cheap line of scatological obsessions. If in the ‘80s, a film like Luger, with its leaden script and graphic scenes of torture porn (the film’s piece de la resistance is a gun being fired up the vagina of a disabled girl), had caused a modest stir when it debuted at the Amsterdam film festival, he soon paid the price for peaking so early. Like Andres Serrano after highly controversial “Piss Christ,” any subsequent production could only be an anti-climax and, as a low-rent pornographer, he was well aware of the diminishing returns to be had from pushing obscenity in a sacrilegious age. Playing epater bourgeoisie in a shameless age is hard work and for most of the post-war period the Netherlands flaunted its decadence with an élan that would have appalled any self-respecting bohemian. In such societies, conspicuous morality is the ultimate transgression and, if the Dutch had lost a sense of the sacred generations ago, its first brushes with Islam in the ‘90s were confronting them with challenges they had not grappled with for centuries. Here was a faith which had taboos in droves and, if van Gogh had inherited none of his ancestor’s talents, he had courage enough to play Voltaire. Insults flew, threats multiplied and soon he was acquiring the kind of enemies any civilised man would be proud to acquire.

Following raucous TV encounters with the likes of high profile Islamist Abou Jabah and a stream of publications like “Allah knows Best,” he was attracting enough death threats to prompt an offer of close protection from the Dutch security and intelligence services. Undaunted and doubtless underwhelmed (the AIVD had been watching Pym Fortuyn, hardly a promising portent), van Gogh pressed on and, in September 2004, he teamed up with Dutch Somali feminist Ayaan Hirsi Ali to produce his final daring blasphemy.

Submission, an amateurish piece of agitprop featuring a naked woman with the offending verses of the Koran projected onto her body, was definitely a step up from the usual profanities, but van Gogh, always more concerned with Hirsi Ali’s safety than his own, retained an uncharacteristic modesty around his achievements. He after all was ‘just the village idiot’. She was an infidel—an infinitely weightier offence at least in the abstract—and, when he set off for work on his bike on the 4th November, he was blissfully unaware of his impending martyrdom.

The very public disembowelment by an Islamist petty criminal in central Amsterdam is by now well-known and the warped mens rea scarcely requires more elaboration than Mohamed Boyeri left pinned to van Gogh’s corpse. The response to this declaration of war on the other hand is so suggestive of the Vichy syndrome afflicting European elites that it needs to be revisited constantly.

Canary in the Mine

As a modish trendsetter for enlightened opinion, the Netherlands, with its long-haired soldiers and militarised social workers, is a symbol of the kind of politically correct Utopia British Left wingers salivate over. No country could be more conspicuously tolerant. And its rise, at the expense of pious counter-enlightenment Spain, offers a ready-made morality tale for those proselytising the benefits of open borders and open minds.

Spain got its xenophobic piety and virtuous poverty, the Netherlands got its stock exchange and Spinoza and this blend of pragmatism and principle provided the Netherlands with all the advantages nature denied her. A rebel waterlogged province in the 16th century, she was a global trading superpower by the 17th and anyone harbouring any doubts on the benefits of their broadmindedness is likely to have them silenced by Amsterdam’s skyline, a stunning tribute to the Northern Renaissance in a country which knew it had not become rich by peering too fastidiously into men’s souls.

All the same, tolerance as conviction, forced upon individuals by the fear of impiously pre-empting grace, is a different beast to tolerance as timid indifference and the history of the Netherlands is at least in part a story of personal piety and republican virtue yielding to a less heroic spirit. Much as its Calvinist patriarchs might have feared, abstention bred riches and avarice drove out virtue. After the excesses of a literally burning conviction, enlightened self-interest could do the heavy lifting and, in a country where institutions have been designed above all to prevent the intrusion of strong beliefs into public life, this enfeebling of the collective conscience has been particularly pronounced.

The Netherlands notoriously had a bad war and, when confronted with their second instalment of barbarism, they responded with similar prudence. That anyone should forfeit their life for a film was doubtless a terrible thing but (there is always a “but”), for many, the most important lesson to be learned was the need to choose one’s taboos carefully. The Justice Minister, Piet Hein Donner (of whom more later), had few doubts; his proposed reintroduction of Blasphemy set the tone perfectly.

“If the opinions have a potentially damaging effect on society, the government must act. It is not about religion specifically, but any harmful comments in general.”

Van Gogh had pierced the squeamish sensibilities of this most conscience-stricken of nations and, in a climate where the right not-to-be-offended enjoys parity of esteem with the rights of free expression, many of the respectable liberal outlets were prepared to bend the knee.

Founded to stand sentinel over the liberties of Europe, the ostensibly nonpartisan Index on Censorship had in fact imbibed so much of Marxisant of the counter culture, that its columnist Rohan Jayasekera could openly snigger at anyone who thought its mission was the protection of Mill’s sole dissenting voice. As he told the British journalist Nick Cohen, this may have been its original youthful purpose, but it was now more concerned with combatting hate crime and, having served up the alibi, he did his worst—penning a sordid attack on a ‘free speech fundamentalist’ who had abused his freedom of speech.

What was his death, after all, if not a sensational climax to a lifetime’s public performance? Stabbed and shot by a bearded fundamentalist, a message from the killer pinned by a dagger to his chest, Theo van Gogh became a martyr to free expression. His passing was marked by a magnificent barrage of noise as Amsterdam hit the streets to celebrate him in the way the man himself would have truly appreciated. And what timing! Just as his long-awaited biographical film of Pym Fortuyn’s life was ready to screen. Bravo, Theo! Bravo!

Strong beer—and enough to trigger some noisy disavowals by the editors—but even if few others debased themselves with quite such élan, there were plenty others willing to see van Gogh’s soft-core porn as a greater crime than his public disembowelment. For Geert Mak, the travel writer cum house historian of the Dutch Left liberal establishment, Submission was on a par with Goebbels’ notorious Eternal Jew and, having effectively invoked the Hitler argument, went on to indulge the inner de haut en bas of the Dutch: lumpenintelligentsia. Unlike the dignified response of Spaniards to the Madrid bombings, he says, “we have only one murder, and everybody goes crazy,” a spasm attributable in large part to the growing pains of a new society . A ‘relatively provincial Netherlands’ (where on earth had Mak been looking?) was opening up to the rest of the world, and the Dutch needed to get used to the trade-offs necessary in a multicultural society. Many, needless to say, have taken the hint and the adjustments made to facts on the ground are clear to see. Amsterdam, as even its proudly ‘out’ mayor Jobs Cohen would concede, is becoming markedly less camp with each passing year, and it cannot be very long before the remnants of its Jewish population make a final choice between anonymity and emigration—an insidious dilemma placed on them by a thousand exorcisms of the liberal mind.

Some truths are literally unthinkable and the Dutch liberal establishment has gone to more trouble than most in pedalling the polite urban myths of multiculturalism. Anyone with eyes to see is aware of what lies behind the record number of attacks on gays for example but, even when confronted with the unpalatable facts, liberal opinion formers sought refuge in some unnecessarily complicated plot twists. The attackers, as the University of Amsterdam ‘Offender Study’ concluded, may have been mostly North African Muslims but clearly many were committed by men with ‘conflicted sexual identities’-a hypothesis which if hardly reassuring to the victims at least enabled Cohen to move the issue beyond a clash of civilisations to therapeutic sound bites.

How many are really convinced by this is questionable, to say the least, and one wonders if Muslims are impressed by the transition from homophobes to homosexuals; but here at least they identified the culprits. With the Jews they elided even this detail. When the European Parliament’s Racism and Xenophobia Monitoring Centre published its report on anti-Semitic violence, it was summarising in strangled academic argot what any Dutch policemen knew—not least those running decoy Jews in the salubrious parts of the inner city. But when the commission suddenly discovered methodological errors and realised that the culprits were mostly neo Nazis, few dared raise the elementary questions and no one was more willing to connive in the doublethink than Cohen who, as a gay Jew, perhaps felt discretion was the better part of valour.

All this is boundlessly depressing and smug liberals who sniff at Trump’s war against grammar would do well to remember the kind of doublethink that sophisticated Europeans have been indulging in for decades. Freedom of speech, needless to say, is still a good thing but, like most things, it can be pushed to extremes. It is through sleights of hand like this that the likes of Cohen have debased the substance of these basic values. So much talk of the “golden mean” just masks the underlying lack of conviction: If an idea is not good in the extreme case, it is simply a bad idea and only someone with the most awry of moral compasses and a deaf ear to Barry Goldwater would claim moderation in defence of freedom-is-a-virtue. We once would have called this cowardice and, in this respect, the Dutch are in good company.

If Europeans can agree on anything it is the evil of conflict, an aversion to megalothymia so engraved in the European psyche that pop Marxist philosophers have elevated it to a symbol of national purpose. The following passages by John Stuart Mill and Jurgen Habermas tell you all you need to know about Europe’s spiritual malaise.

War is an ugly thing, but not the ugliest of things. The decayed and degraded state of moral and patriotic feeling which thinks that nothing is worth war is much worse. The person who has nothing for which he is willing to fight, nothing which is more important than his own personal safety, is a miserable creature and has no chance of being free unless made and kept so by the exertions of better men than himself. (J. S. Mill, The Contest in America, 1862)

What forms the common core of the European identity is the character of the painful learning process it has gone through as much as its results. It is the lasting memory of nationalist excess and moral abyss that lends our present commitments the quality of a peculiar achievement. This historical background should ease the transition to a post-national democracy based on the mutual recognition of the differences between strong and proud national cultures. Neither assimilation nor coexistence–in the sense of pale modus vivendi–are appropriate terms for our history of learning how to construct new and ever more sophisticated forms of ‘solidarity amongst strangers.’ Today, moreover, all European nation states are being brought together by the challenges which they all face equally. All are in the process of becoming countries of immigration and multicultural societies. All are exposed to an economic and cultural globalisation that awakes memories of a shared history of conflict and reconciliation–and of a comparatively low threshold of toleration towards exclusion. (Jurgen Habermas, “Why Europe Needs a Constitution,” New Left Review, 2001)

Can anyone read these statements and the embodied sensibilities and not detect a fading grandeur in the sentiments of the 21st century?

Enlightenment Fundamentalists

To judge by the tone of the abuse heaped on Hirsi Ali, one might have thought she was little more than a narcissist with a cause. Geert Mak’s heavily laden nom de guerres of Somali princess and his tasteless diatribes on her Joan of Arc complex typifed the sneering tone of so many progressive commentators who might reasonably have been expected to offer succour. But perhaps the most tasteless attacks related to the question of her bodyguards.

By any stretch of the imagination these were not frivolous accessories and, after van Gogh had paid the price for his modesty, a civilised government might have seen them as a necessary part of the state’s compact with its citizens. Even here, however, freedom of speech was weighed in the balance and, in a particularly shameful act of parsimony, the Justice Ministry announced the withdrawal of funding for her security detail leaving her with few options other than flight to the New World, the first refugee from Western Europe since the holocaust.

It is a sordid episode in the history of post-war Europe and even now it is difficult to credit the witch’s brew of vicious resentments stirred by someone who in saner times would have been hailed as a progressive feminist icon. Much of the explanation inevitably lies in the narcissism of small differences but some of it, too, is clearly driven by the joys of hatred.

To a well-bred ideologue operating in the starched and humourless atmosphere of the Left, with all its aborted thoughts and anxious taboos, is to be in the position of someone permanently hoarding their vengeance. All they need is the necessary cover and Hirsi Ali-like Zionist bogeymen, and vacant railway carriages provide it in spades. Everything she has done in her subsequent incarnation—from nesting in neo-con think tanks to marrying an unfashionably Right-wing historian—has fired this indignation and nowhere have these heights of psychological self-indulgence reached a grimmer frenzy than amongst genteel intellectuals.

As a piece of character assassination, Ian Buruma’s “Death in Amsterdam” has few equals; its distinctively vindictive tone sharpened by a penchant for Soviet-style genealogies designed to paint Hirsi Ali as an emotionally scarred and unsophisticated zealot. Much of it is merely tasteless; readers will draw their own conclusions as to why Buruma felt compelled to linger on the death of Hirsi Ali’s sister or her childhood infatuation with Danielle Steele novels, but the real purpose of these creepy ad hominems is revealed in a relentless deconstruction of western values. Thus, amongst other canards, the suggestion that, Ayaan, “having succumbed to fundamentalist influences in her youth similar traits could be detected in her conversion to a ‘slightly simplistic Enlightenment fundamentalist.’”

“Enlightenment fundamentalist.” Now, there is an arresting oxymoron. It is difficult to credit that Buruma, an accomplished Sovietologist and keen student of the kind of persuasive definitions communists used to debase language and meaning, did not know what he was doing with this sinister neologism but, even if one were inclined to be generous, further passages give enough context to dismiss the idea of a slip of the pen. Thus, at first sight, the class values appear to be straightforward—on the one hand, secularism, science, equality between men and women, Individualism, freedom to criticise without fear of violent retribution and, on the other, divine laws, revealed truth, male domination, tribal honour, and so on. It is indeed hard to see how, in a liberal democracy, these contrasting values can be reconciled. How could one not be on the side of Fritz Bolkstein, Afshin Elian, or Ayaan Hirsi Ali?

Ian Baruma writes in Murder in Amsterdam: The Death of Theo Van Gogh and the Limit of Tolerance:

A closer look reveals fissures that are less straightforward. People come to the struggle for Enlightenment values from very different angles and, even when they find common ground, their aims may be less than enlightened.

. . . struggling against oppressive cultures that force genital mutilation on young girls, and marriage with strangers on young women. The bracing air of universalism is a release from tribal traditions.

and

. . . But the same could be said, in a way, of their greatest enemy: the modern holy warrior, like the killer of Theo van Gogh. The young Moroccan-Dutch youth downloading English translations of Arabic texts from the Internet, is also looking for a universal cause, severed from cultural and tribal specificities.

And for light relief, a personal favourite of Hirsi Ali’s, fellow apostate Afshin Ellian, with comment (via Buruma) that might have graced Private Eye’s “Pseuds Corner” column.

Why should Westerners be the only ones to dissent from their traditions, he wondered. “Why not us? It is racist to think that Muslims are too backward to think for themselves.” He spoke with passion, and more than a hint of fury. I admired his passion, but there was something unnerving about his fury, something that reminded me of Huzinga’s idea that dangerous illusions come from a sense of historical wrong. (Buruma, see above)

This is, to be sure, not quite an endorsement but one wonders at the obsessive even-handedness. The effect of Buruma’s first two paragraphs—when one gets away from all the polite double negatives—is to put the two belief systems on the same moral plane. All this, and Buruma’s obsequies to Ramadan, should have alerted agile minds to the mischief of the phrase “Enlightenment fundamentalist” but, in a review of Murder in Amsterdam, Timothy Garton Ash chose to give it a second tawdry outing and for good measure threw in few calumnies of his own.

Sniffing his way condescendingly through an article, which predictably ended with a warning against simplistic parodies of Islam, Ash took care to point out that Ayaan had won the glamour award adding (in case there was any doubt), “If she had been short, squat, and squinting, her story and views might not be so closely attended to.” Nice. The war of words sparked by Ash’s ungallant column is by now knowledge, courtesy of Paul Berman’s racy polemic The Flight of the Intellectuals: The Controversy Over Islamism and the Press, something of a cause celebre—a series of increasingly ill-tempered exchanges between Pascal Bruckner, Timothy Garton Ash, and Buruma—raging across the pages of German periodical “Sign and Sight.” Bruckner’s point was a simple one: whilst leaving themselves free to savour the bracing freedoms of citizens-of-the-world, both nevertheless looked disapprovingly on Hirsi Ali’s apostasy. She had, as both of them sniffed, left her community, and lost her ability to speak to the people of Brick Lane and, hidden in the purple prose, was the subtext that she should have stuck to her millet. To Bruckner, a quintessentially French republican intellectual-cum-moralist, this was more than the condescension of compassion, it was ‘the racism of anti-racists’ and screamed for vengeance.

Bruckner wrote:

Under the guise of celebrating diversity, veritable ethnic or confessional prisons are established, where one group of citizens is denied the advantages of another. Nothing is missing from the portrait of the young woman painted by Timothy Garton Ash, not even an outmoded machismo. In his eyes, only the beauty and glamour of the Dutch parliamentarian can explain her media success; not the accuracy of what she says. Garton Ash does not ask whether the fundamentalist theologian Tariq Ramadan, to whom he sings enflamed panegyrics, also owes his fame to his Playboy looks. Ayaan Hirsi Ali, it is true, does elude current stereotypes of political correctness. As a Somali, she proclaims the superiority of Europe over Africa. As a woman, she is neither wife nor mother. As a Muslim, she openly denounces the backwardness of the Koran. So many flouted clichés make her a true rebel, unlike the sham insurgents our societies produce by the dozen. It is her wilful, short-fused, enthusiastic, impervious side to which Ian Buruma and Timothy Garton Ash object, in the spirit of the Inquisitors who saw devil-possessed witches in every woman too flamboyant for their tastes.

A mighty sword had flashed in its scabbard and by the time Bruckner’s missive hit the press he was already in good company. The flower of France’s New Intellectuals had piled into the affray with j’accuse outrage and were joined poignantly by the former East German dissident Ulrike Ackermann who hurled well-earned criticism at her fellow travellers and former friends, Buruma and Ash. For someone like Ash, an honourable Cold Warrior whatever his faults, that must have been a wounding reproach, but he fearlessly returned to the fray in an article in the Guardian which for sheer tenacity of purpose is second to none.

Having blundered into a theological minefield, Ash had taken it upon himself to dig deeper into those subtleties of Islam which, in his view, were beyond the reach of an untutored Somali. He had become infatuated with Sheikh Gamal al Banna (elder brother of Hassan al Banna), ‘a man of tranquil clarity’ and the possessor of a library which evidently made quite an impression on the intrepid Don. Al Banna was, on the face of it, just the kind of interlocutor who a liberal would seek out when striving to avoid a “simplistic parody of the real diversity of Islam.” He held progressive views on the stoning of adulterers and apostasy; he prefers to anathematise (it is surely a symptom of how low we have fallen that Garton Ash hails this as a new humanism) rather than kill, “and yet he is something Hirsi Ali can never be: a pious Muslim with the ability to reach millions.” Warming to a familiar theme, he laid out two quotations on hadiths—one that had been provided by Hirsi Ali and one provided by Gamal al Banna—before asking his readers, “Which do you think reveals a deeper historical knowledge of Islam? Which is more likely to encourage thoughtful Muslims in the view that they can be both good Muslims and good citizens of free societies?”

The question evidently only had to be asked to be answered: how could a devourer of Mills and Boon ever hope to compete in the arts of sacred exegis with such a cultivated scholar? One could sense the purring contentment as he penned his lapidary comments. How could one come back from this tour de force?

It was an incautious endorsement and, at the time he offered up his burnt offering to the Guardian, hubris was already beating its wings. The worldly Professor had published his piece on the same day that the Middle East media research unit had published a less flattering summary of the sheikh and the reading was sobering.

About 9/11, for example, Sheikh Gamal Al-Banna was unequivocal several days after the attacks (9/21/01). “It is the criminal and racist American foreign policy against the repressed peoples of the world, and primarily against the Arab and Muslim peoples, that is to blame for the New York and Washington events, whatever the national identity of the perpetrators . . .” And, for added discomfort, there is this:

Martyrdom operations in Palestine, in particular, are justified for two reasons. First, the Palestinians do not have weapons to defend themselves. They have no tanks, artillery, and so on. This is the only means available to them. Therefore, it is justified, especially since it is the Israeli soldiers that are targeted. When I say ‘soldiers’ – the entire Israeli people is recruited. The women are the most vicious of them all. Therefore, this is justified. I consider this to be martyrdom. Even if they harm a woman—all the women serve in the army. All the men serve in the army. Only the small children remain and the fact is that these are only very rarely harmed. I believe that these are martyrdom operations and are necessary. (Memri.org)

We flee a clash of civilisations for this? It seems almost redundant to point out that al Banna was undecided on hand chopping (we should doubtless be reassured the equivocation reflects a utilitarian rather than theological indecision), and one is left to marvel how a man otherwise so faithful to the habits of sceptical British empiricism (Berman’s speculations on hidden blood lusts are entirely wide of the mark—Ash is uncontaminated by postmodern fascinations with violence and fanaticism) could have been taken in by such charlatans.

In part, surely this is the inevitable result of setting a low bar. Compared with cartoonish Bond-like villains such as Anjem Choudhry and Abu Hamza, the likes of Tariq Ramadan and Yusuf Quaradawi do look like effete liberals and one can understand why men of honourable intent grope for the lesser evil but much of it also stems from a basic failure of imagination.

Soviet Marxism, the enemy Ash felt most comfortable with, took itself woefully seriously as the culmination of Enlightenment rationalism and was uniquely vulnerable to the kind of battle of ideas a sharp donnish mind might excel in. But what is one to do with cruder chiliastic ideologies, strewn with violent injunctions against the impiety of cold, calculating, reason while populating feeble minds with virgins and raisins? How do liberals respond when confronted with creeds that think with their blood? It is a question that was never answered satisfactorily in the thirties and Ash seemed no nearer to an answer when he faced Hirsi Ali in a follow up debate at the Royal Society of Arts in London

Gobbledygook

Having experienced a degree of vitriol normally not encountered in academia, Garton Ash was in conciliatory mood, and a big enough man to retract a “misunderstood phrase.” “It had not occurred to him,” he said, “that anyone would be so idiotic as to imagine that I was constructing any similarity between Islamic fundamentalists and Enlightenment fundamentalists,” a testy piece of contrition to be sure, but still, “Enlightenment fundamentalist” had gone and the short-squint-squat remark was also given a decent burial (he had meant it as a complement). Ash moreover made it clear that he had no doubts all the interminable odium theologicum and laborious weighing-in-the-balance of every Hadith and Sura was just much dancing on the end of a pin. “It was,” as he frankly put it, “all gobbledygook,” but, “if it is all gobbledygook, anyway, and I think it is gobbledygook, then we should prefer a version of gobbligook that is more compatible with a liberal society.”

Useful gobbledygook? It is perhaps not such a strange idea for Straussians and reactionaries; the noble lie has been around a long time. Still, it is unusual for a progressive to advertise his prejudices so candidly and Ayaan was left with an easy flank to term—“if you treat people like children, they may act like children.” Quite what is orchestrated gobbledygook but the racism of anti-racists?

Undeterred, Garton Ash ploughed on and drew on all his accumulated reserves of academic prestige to score a mighty blow. As a historian, he gravely remarked, he had started his career studying the anti-Hitler conspirators and, in pondering this noble cause, had been obliged to reflect on the disagreeable characteristics of many of them. The implication was clear—we cannot pick and choose our Muslim dissidents. For a distinguished historian, it was a strange thing to say—even the average viewer of the History Channel could tell you that the allies made no attempt to foment a fifth column, opting to crush the Nazis and drain the rather expansively defined ideological swamp. No compromises with Christian aristocrats, national Bolsheviks or wiley Nazis were entertained and, if he was foolish enough to think this imaginary precedent offered a crisp policy prescription, it is a relief that even the normally supine British establishment now swerves from the temptations of ideological cross-contamination.

After years of cultivating fellow travellers, the Prevent strategy is now as preoccupied with nonviolent extremism as it is with the ancillary instruments of terror and, if such epiphanies can dawn in the dullest of political minds, how much more should we expect from a Professor of European History?

Dialogue can be a dangerous thing when confronting barbarians. When one is expected to confront such questions as the desirability of stoning adulterers and killing apostates on the basis of pearls of wisdom drip-fed by acceptable clerics meditating earnestly on the sayings of a seventh century Holy book, it is a sign that we have set the bar of civilisation too low.

Hirsi Ali, needless to say, has experienced the effects of this debasement of ethical standards before the various Islamist fronts which hold the ear of western governments and it is a mark of the corrosive effect of these dialogues that Islamists now have the confidence to change the terms of the debate. A telling case in point is Ramadan’s assault on a liberal shibboleth; tolerance of Islam is now considered an insult. Ramadan wrote, “When standing on an equal footing, one does not expect to be tolerated or grudgingly accepted.” Self-respecting Muslims now demand unconditional affirmation using justifications which draw on all the moral authority of decadent modern liberalism (Ramadan’s point could have as easily been made by Charles Taylor or Kymlika). Dare-to-know gives way to an altogether soggier therapeutic injunction and it is curious that liberals who prize the virtue of irony imagine that they can compete in this shrill atmosphere with individuals who can arm themselves with a thousand sleights.

Given his second incarnation as a purveyor of weighty book stops, Ash is sticking to the task—even if the effort of stretching bien pensant banalities over 500-pages defeats his considerable literary powers. If Facts are Subversive was heavy going, Ten Principles for a Connected World is just plain tedious. Take the following nonsense on the Muslim reformation from Ash’s Free Speech: Ten Principles for a Connected World:

Olivier Roy, one of the finest analysts of contemporary Islam, makes a subtle observation. Referring to the Islamic ‘neofundamentalism’ that, he argues, appeals especially to second- and third-generation European Muslims of migrant origin, he observes that ‘neofundamentalism is a paradoxical agent of secularisation, as Protestantism was in its time . . . because it individualises and desocialises religious observance.’ Thus, for example, Lamya Kador, who describes herself as a ‘German of Muslim faith with Syrian roots,’ goes on to insist: ‘it’s not up to others to tell me what Islam is or should be: I want to decide for myself how to live my Islam’. This individualised version of Islam has, in a sense, already taken on board that core message of the Enlightenment: think for yourself. She chooses to believe in her own way.

It is a surreal observation and the cachet Roy enjoys as an expert on Islam is in itself an indication of how far we are from getting to grips with the problem; just ponder for a moment the credulity necessary to read into this a reassuring message. This stripped down a la carte Islam, shorn of any mitigating high culture which might temper its cruder maxims and which seeps into uneducated minds at the intellectual level of daytime TV, is the problem not the palliative. To imagine that the elements of doubt that must creep in are in themselves grounds for optimism is to misunderstand the roots of fundamentalism. The latter is, after all, evidence of the weakness of faith and nothing displays this more than the refusal of doubt. A strong faith can take someone all through the tribulations of Job. The creed of the Muslim lumpen proletariat, by contrast, smacks of a triumph of the will.

If a self-styled intellectual like Tariq Ramadan admits that doubt is literally unthinkable, and if we can expect this from someone who quotes Flaubert, how much less can we expect from the unlettered disciples who flock to his Salafist banalities? To talk of engaging in a war of ideas with such people is a basic error; particularly when one considers the cramped immature personalities to which these feeble tautologies appeal. To a burgeoning underclass, pious talk of welfare as a form of jizya is a soothing balm and, in the penal system where taxpayers’ money funds the most virulent Salafist propaganda, we see the ultima ratio of where this ideology leads: a series of lazy syllogisms providing criminals with all the advantages of an honour cult and none of those strenuous exertions of the soul. A typical example (which as an occasional frequenter of prisons I am aware of): by way of courtesy of the imams, many prisoners earnestly believe (or at least have received a pious warrant for a base inclination) that whilst drug dealing is haram, it is nevertheless permissible to steal from those who sell them. What sociopath would not grasp at these lazy Jesuitical formulas and, what wonder the spread of this cult amongst prisoners, who might otherwise have had to labour at a sociology degree to spare themselves a conscience?

The fact that in some profound sense, it embodies a contradiction (Fukuyama in ponderous moments of Hegelian faux profundity makes great hay of this), or that it does not provide a viable ethic for living in a modern post-industrial society is a moot point—they have, for the while, a healthy host and can draw on unlimited reserves of wishful thinking. To judge by the flippant pronouncements of European politicians, one might imagine that the odd murder or queer-bashing were small costs attendant on the greater benefits of a youthful injection to stagnant populations but no semi-literate economist would look at the unemployment rates of the Netherlands and conclude they are the saviours of an ageing population. After decades of confident pronouncements in Holland that Muslims would soon beat a path to the contented semi-prosperity that Surinamese migrants reached in the eighties, the sleights of hand necessary to ignore stubborn facts are becoming ever more desperate. For Mak, the problem is one of peasants and stubborn village habits. One would presumably encounter the same problems if Denmark exported its rural surplus and the larger political questions surrounding multiculturalism remain agonisingly fraught.

Officially, the problem does not exist: Europe is awash with noisy disavowals from its political elites but anyone taking these statements as the opening salvo in a confident restatement of western values would have been sorely disappointed.

Multiculturalism was always more a nihilist sensibility than a policy and, even if it has jettisoned a catchphrase, it is no closer to acquiring a belief. The result—even after a thousand sermons on Britishness or “core cultures”—is that multiculturalism remains as a demographic fact on the ground and its terminus is pretty clear even if most Europeans still refrain from the honesty of the Dutch Justice Minister.

Confronted with demands from opposition CDA parliamentary leader Maxime Verhagen to ban Sharia law from ever reaching the statute books, Justice Minister Piet Hein Donner responded with shrill outrage. “For me it is clear; if two thirds of the Dutch population should want to introduce Sharia tomorrow, then the possibility should exist. It would be a disgrace to say that it is not allowed!”

Here, at least in the postmodern liberal bazaar, we have some iron certainty.

To comment on this article, please click here.

_________________________________

Robert Bruce is a low ranking and over-credentialled functionary of the British welfare state.

To help New English Review continue to publish interesting articles, please click here.

If you enjoyed this article by Robert Bruce and want to read more, please click here.