by Kenneth Francis (January 2020)

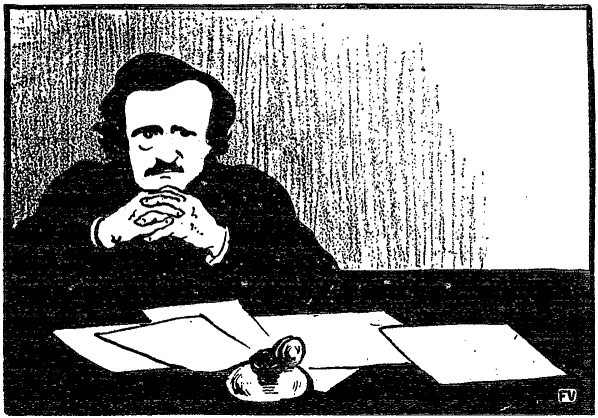

Edgar Allan Poe, Felix Vallotton, 1895

The 19th day of this month celebrates the birthday of one of America’s greatest short-story writers, Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849). When his name is mentioned amongst the literati or the average bookworm, images of madness, death and the macabre spring to mind. Poe is almost synonymous with everything eerie, from psychopaths killing black cats to grisly murders in a morgue. It is worth briefly looking at a few of Poe’s best-loved works.

In the classic short story, Tell-Tale Heart, the killer hears all things in Heaven, Earth, and many things in Hell. But was Poe, who was raised Catholic, religious? And did he believe in Heaven and Hell? One thing is for sure: Everyone who reflects on life, including Poe, has a theology of sorts.

Read more in New English Review:

• A Story-Telling Decalogue

• The Demise of Jeremy Corbyn

• Remembering Don Emilio

Some of the themes in the Tell-Tale Heart seem theologically inspired, whether consciously or unconsciously, while others are true-to-form Poe at his psychological best. The story was first published in January 1842 in the Boston ‘Pioneer’. The dramatic monologue begins with a narrator talking about nerves, madness, Heaven and Hell:

TRUE! —nervous—very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses—not destroyed—not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How, then, am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily—how calmly I can tell you the whole story.

We see the Bible reference here from Philippians 2:10: “That at the name of Jesus, every knee should bow, of things in heaven, and things in earth, and things under the earth”. We can also see that the narrator’s personality is leaning toward evil. And what can be more dangerous than the cunning of a lucid evil person?

Poe never mentions the sex of the protagonist, but there is something quite masculine about this character. Assuming he’s male, he could be either a lodger or carer for the old man, but it’s doubtful that he’s his son, as he doesn’t refer to the old man as ‘father’ or ‘pop’ but ‘old man’.

Another great short story by Poe is The Black Cat. Here, the mad narrator talks of the killing of his favourite feline pet:

. . . And a brute beast—whose fellow I had contemptuously destroyed—a brute beast to work out for me—for me a man, fashioned in the image of the High God—so much of insufferable woe! Alas! neither by day nor by night knew I the blessing of rest any more! During the former the creature left me no moment alone; and in the latter I started hourly from dreams of unutterable fear, to find the hot breath of the thing upon my face, and its vast weight—an incarnate nightmare that I had no power to shake off—incumbent eternally upon my heart!

The narrator acknowledges his wretchedness. And he recognizes the existence of God, whose amazing grace could only save a wretch like him. But both theologically and psychologically his actions and frame of mind are profoundly complex and beyond theism, atheism and nihilism.

Has there ever been a more complex character in the history of literature? A murderer who speaks well of his soon-to-be slain wife but is more concerned with the death of his cat? Does such a madman exist biographically somewhere in the depts of Poe’s id? After all, Poe was a sinister, dark alcoholic who owned a cat.

In his poem, The Raven, Poe writes about the nights plutonian shore, referring to Hell the underworld; and he adds, “By that Heaven that bends above us, by that God we both adore . . . ” and “Get thee back into the tempest and the Night’s Plutonian shore! Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken! Leave my loneliness unbroken! —quit the bust above my door! Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!’ Quoth the raven, ‘Nevermore.’”

But Poe never makes it clear whether or not he is atheist or theist. His adopted father, John Allan, had in 1812 his boy, Edgar, baptized in the Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia. Edgar and his foster mother, Frances, were later regular attendees at the newly built Monumental Episcopal Church after 1814. And the young Poe was taught the catechism while living in England, but his later attendance at church is unknown.

Writing in the New York Times, Jonathan Wolfe states when Poe lived in a cottage in the Bronx, “he visited the Jesuits at a nearby college, now part of Fordham University. He was fond of the order, he told an acquaintance, because they ‘smoked, drank and played cards like gentlemen, and never said a word about religion.’” However, some of Poe’s writings seem to show a pro-religious leaning.

According to C. Alphonso Smith, Poe and the Bible: “There is abundant evidence that, from early childhood when Poe went regularly to church with Mrs. Allan in Richmond, to that last hour when he asked Mrs. Moran from his death bed whether there was any hope for him hereafter, God and the Bible were fundamental and central in his thinking.”

Alphonso Smith goes on to say that it is equally evident that, though living in a sceptical age, an age in which science seemed to be weakening the foundations of long-cherished beliefs, and being himself an adept in scientific hypothesis and speculative forecast, Poe remained untouched by current forms of unbelief.

More than this, he was a positive force in the overthrow of scepticism and in the establishment or reestablishment of faith and hope. It is hard to understand what Mr. Woodberry means when he records the fact that Mrs. Moran read to the dying poet the fourteenth chapter of St. John’s Gospel and adds: ‘It is the only mention of religion in his entire life.’

If the mere reading of the Bible to Poe, not by him, be construed as a ‘mention of religion’ in his life, what shall be said of his own familiarity with the Bible, of his keen interest in Biblical research, of his oft-expressed belief in the truth of the Bible or of his final and impassioned defence, in Eureka, of the sovereignty of the God of the Bible? (C. Alphonso Smith, Poe and the Bible, Biblical Review, vol. V, no. 3, July 1920, pp. 354-365)

As for Poe’s contribution to literature: every line and paragraph in Poe’s works are written with such elegant turn of phrase and style, that the reader is instantly seduced by his brilliant storytelling skills, including his poems.

Read more in New English Review:

• Tom Wolfe’s Mastery of Postmodern America

• Cuisine for the New Inquisition

• Two Literary Sermons

Annabel Lee shows a romantic side to the dark genius of Poe. Anyone who is not saddened by the poignancy of the last verse where the narrator laments the death of his loved one, would have to have a heart of stone: When a ‘wind came out of a cloud by night, chilling and killing my Annabel Lee.’ Poe concludes:

. . . For the moon never beams without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And the stars never rise but I feel the bright eyes

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride,

In the sepulchre there by the sea,

In her tomb by the sounding sea.

Poe died on October 7, 1849. The case of his death and the circumstances leading up to his demise remain a mystery. On October 3, four days before his death, he was found very distressed in Baltimore, Maryland, when he was taken to Washington College Hospital, where he later died, on the 7th, at the relatively young age of 40. To this day, no one knows what happened to him.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Kenneth Francis is a Contributing Editor at New English Review. For the past 20 years, he has worked as an editor in various publications, as well as a university lecturer in journalism. He also holds an MA in Theology and is the author of The Little Book of God, Mind, Cosmos and Truth (St Pauls Publishing) and, most recently, The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Theodore Dalrymple).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast