The Things in the Attic

by Armando Simón (October 2022)

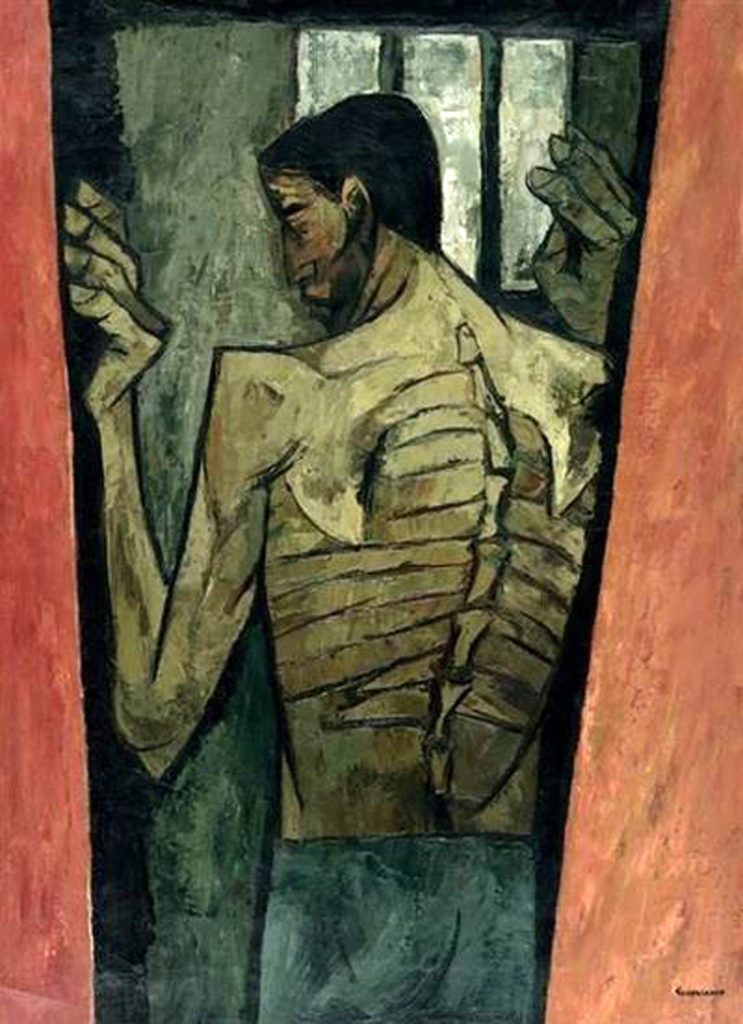

El Prisionero, Oswaldo Guayasamín, 1949

Soon, it would be twilight on a cold, winter day, with grey overcast skies that kept out the blue heavens. The lights on the lampposts had gone out a while back; the incompetent city managers had not fixed the problem, for one reason or another. One of the lights, though, flickered on and off.

Inside one of the two-storied houses, a lean man stood behind an upper story window, looking down at the street, lined on both sides with skeletal brown trees that had lost their leaves. A leaf could still be seen here and there hanging on tight for dear life on one or two trees, although they too would soon probably disappear from sight.

The man, motionless and with mild expectancy, held open the heavy, opaque, curtains of the window with the back of the fingers of one hand and looked down upon the street. Out of habit, he held his other arm rigidly behind him, at a right angle, his hand in a fist. He was tall, held himself erect effortlessly, giving a patrician impression. This impression that one automatically felt was also due to his graying temples and to facial expression rarely revealing what he felt, a good habit to employ now that, more and more, he felt disdain towards people that he came in contact with. Nonetheless, he could adopt small smile to put others at ease in order to minimize possible escalating irritations, or sometimes out of politeness, Yet, few people felt at ease with him when they would first meet him.

And, yet, there was something vague about him that captivated one, something that one could not put a finger on. Rarely talkative, he was standoffish, courteous but not pleasant. One got the definite feeling that he would much rather not be around you. Spending any amount of time around the man, one felt him to be the coldest, uncaring person around while others would think him a warm individual.

Some women would have thought him definitely handsome. Some women would have thought him definitely not handsome. But no one would have thought him ugly.

Only his wife, who had been killed by a drunken illegal alien—make that an “undocumented immigrant”—from El Salvador that received only six month’s jail time, knew that her husband was thinking, thinking, always thinking, that his brain had a broken “off switch.”

Yes, he was always thinking.

As expected, a black car leisurely drove up the street and parked near his house. Two occupants walked slowly towards his home.

He calmly descended downstairs as the doorbell rang. Stopping momentarily to assess himself, he unclenched his fist and brought his arm to the side to let it hang so as to not give the impression to these professionally suspicious officers that he held a weapon behind him. He adjusted his facial expression to one he knew from past experience gave off a slight feeling of unwelcoming arrogance and opened the door. Releasing the doorknob, both arms hung by his side, unmoving.

“Hello. I’m Agent Gerald Bakker with the Federal Bureau of Inclusiveness,” a balding man in his forties introduced himself, “and this is Agent Gladys Bonnet.” He motioned to his partner, obviously a former man who had decided to become transgender and now saw himself as an attractive woman whereas, in reality, it was undeniably grotesque, though no one would say so in this day and age. He looked them over.

“I’ve been expecting you.”

Both agents subconsciously felt a mild uneasiness at the man’s posture. Though they did not consciously voice the reason in their heads why this was so, it was because a person who answers a door always leaves a hand on the door, or the doorknob.

“Are you Derek Trueheart?”

“Yes.”

“Mr. Trueheart—”

“Dr. Trueheart, if you please,” he interrupted.

Bakker glanced at his papers. “Dr. Trueheart. Sorry. Yes, you phoned in a denunciation against your neighbors, the Cirulli family. Ah, may we come in?”

“Certainly. But I must insist that you remove your shoes prior to entering. It’s a rule in my house. No exceptions.” They saw that he was shoeless, walking in socks. “A rule I adopted while in Asia and brought back. You see, I have severe mysophobia—a phobia of germs and dirt.” He decided to put on a slight smile on his face and did so.

“Isn’t that a handicap in your line of work, as a doctor?” Grotesque Gladys asked.

“Not really. Actually, it’s an advantage if you think about it. And it’s the reason that I went into medicine in the first place,” he lied. The agents realized that there was a certain logic to it. “Now, if you care to remove your shoes—” he opened the door wider, deceptively inviting them in.

“That’s OK,” Bakker said.

As expected.

“What we have to say can be done in a few minutes.”

So predictable. The situation now didn’t call for extended pleasantries. Good. He dropped the smile.

“You denounced the Cirulli family to our office,” he continued.

“Have you caught them yet?”

“Not yet, but we will. It’s only a matter of time,” Grotesque Gladys answered in a confident tone.

“I imagine that you’re overworked rounding up all those Republican and Libertarian fascists. The sooner you catch them all, the sooner we can establish a proper democracy,” Trueheart repeated the mantra being broadcast on a daily basis throughout the television and the radio. “We cannot tolerate their divisiveness. It’s detrimental to a democratic society.”

“Well, with few exceptions, like the Cirulli’s, rounding them all up has been easy. After all, during the previous elections, they registered party affiliations. They just stay put in their homes and we pick them up. The trouble now is housing them in the re-education camps. They’re so overcrowded.”

“Serves them right,” Trueheart said. “Those racists don’t deserve to be pitied.”

“Anyway,” Bakker said, trying to conclude, “seeing as to how you denounced them to the authorities, you now have permission to enter their home and confiscate any of their belongings for your personal use.” The agent handed him an official permission of entry.

“Just try to leave something for the new residents, would you?” Gladys smiled wickedly.

“Any idea who they might be?”

“Either a family of immigrant Muslims or Africans,” Bakker said “They should arrive in a few weeks, before the end of the month.”

“Good. This neighborhood needs more Diversity. The more black and brown skinned immigrants from impoverished Third World countries, the better. Oh, and what about the yellow tape wrapped around their door and windows?”

“You can tear them off now. You have official permission to enter the premises.”

“And Cohen?” he inquired.

“Pardon?”

“Cohen, across the way,” he motioned with his head. “He also denounced the Cirullis. Doesn’t he get a piece of the action?”

“Yes, he does. We’ll bring him his own permission tomorrow, same time. Since you were the first to turn them in, you get first choice,” Bakker said.

“We have found that that rule reduces inhibitions for people to report right-wing extremists,” Grotesque Gladys explained. “It’s kind of like it creates competition. People don’t want to be left out of the benefits of turning people in to us. So, you get a head start.”

“Ingenious idea,” Trueheart had to admit. “All right. Thank you.”

“Well, goodbye.” The agents returned to their car and departed. They could see the doctor still at the door watching them leave.

That went smoothly. And since they did not come in, no microphones were planted. Not that they had any reason to do so. But these days …

He went inside, closing the door behind him as he read the document. It was brief and to the point.

Dr. Trueheart stood still for a minute and sighed. It was going to be tedious. He deeply disliked anything that was tedious, regardless of its necessity. Fortunately, he had long ago planned for the looting, had a list of things to get, empty boxes and bags ready to carry the Cirullis’ belongings to his home. The dolly in the garage would help. But it would still be tedious.

Putting on a windbreaker for the chill, he entered the garage and stacked the boxes and bags on the dolly, along with a flashlight, a portable lamp, and a knife, then stepped out into the darkness.

He walked over to his neighbor’s house pulling the dolly behind him, saw the various pots harboring desiccated plants, and lifted the botanical corpse from the third pot, revealing the key to the house. Because of his knife, the tight yellow tape now hung limp.

He entered the Cirullis’ home and turned on both the lamp and the flashlight after ascertaining there was no electricity available.

It was stuffy.

Considering the shortage of food these days, with the many empty shelves in the markets, he made a beeline for the kitchen and the pantry. As expected, they were well-stacked with food and his boxes and bags were quickly filled with canned and other prepared food. Some kitchen utensils, glasses and dishes made their way to the boxes as well. He quickly took the items to his home and dumped them on the floor before returning for the second run for food. On arriving at his house, he did not bother to take off his shoes, though he would do so afterwards, to relax. Although he did regularly take off his shoes inside the home and insisted that any visitors going in do the same, a most excellent Asian custom, the mysophobia story had been a lie in order to make others comply with his rule. And to make the agents ill at ease. Simple manipulation.

Back at the Cirulli home for the third time and, even though he knew he should not, he opened the refrigerator door to see if any food was salvageable, and instantly regretted it.

Next, he went to the master bedroom and put the husband’s and wife’s jewelry in a bag. He dragged the chest of drawers forward, and with one hand, groped the back, finding a manila folder full of money taped to the chest and he put that in the bag.

The doctor then went to their bathroom and with some disgust put the woman’s abundant cosmetics on another bag. He also collected soap, toothpaste, toothbrushes, toilet paper and some towels. The empty shelves at stores were not confined to just lack of food.

Dr. Trueheart found the handgun, along with the ammunition and his hastiness momentarily stopped as he weighed his options. Owning a personal handgun was now highly illegal, and yet … Besides, if he left it in the premises the new residents would find it and there was no way to predict how they would act, what they would be like. In the end, he included it in the items.

He checked his list by flashlight. He collected next the photographs and various education and medical documents.

He gathered some of Cirulli’s clothes, including his underwear and did the same with his wife’s clothes, smirking at a couple of thongs. He even tossed in a few hangers. Blankets, bedspreads, pillows went in.

Returning for another load, he collected the clothes of the teenagers and packed them in the boxes. It occurred to him to get dishwashing and laundry soap.

He had all the items that had been on his list, but he was not finished. Now, he took his time to look over the place, going from room to room at a leisurely pace.

The Cirullis had had good taste and no question about it. There was an Erté painting on the wall that he had long coveted and the same was true of four exquisite, though fragile, Lladró ceramics. He would take them to his home carefully, making sure that they were not damaged.

He found a bottle of amontillado and another of Amaretto di Saronno and for the first time genuinely smiled. He poured amaretto in a brandy snifter, closed his eyes, slowly inhaling the heavenly fumes and just as slowly drank it, savoring it. For the first time that day, a calmness came over him.

Trueheart walked over to a bookcase and nodded. Her taste in literature is almost as good as mine. Almost.

Even though he had duplicates of the volumes, he would nevertheless bring a lot of them: Twain, Vonnegut, Marcus Aurelius, Orwell, Cooper, Maupassant, Dumas, Poe, Shakespeare, Dostoyevsky, Soseki, Asimov, Thomas Wolfe, Dos Passos, Sienkiewicz, Unamono.

There were also books whose possession of them was an automatic prison sentence, works by Solzhenitsyn, Koestler, Ayn Rand, Margaret Mitchell, Edmund Burke, and other than literature, history books: Conquest’s The Great Terror, autobiographies of Ronald Reagan, Theodore Roosevelt, and Margaret Thatcher, Carlyle’s history of the French Revolution, a biography of Lincoln (Lincoln was now officially a racist and a white supremacist) and others.

He was finished with the confiscation, having taken well over an hour. Being organized beforehand had shortened the time that would have been required to cart everything away by more than half. Outside the darkened, abandoned, home, he locked the door behind him and put the key in his pocket.

Halfway back, he stopped in the darkness, listening. It was a nearby owl, giving its melancholy, slow call, its hoo, hoo. Trueheart had been hearing him almost every night now. It always sounded to him like such a sad, lonely voice, and although he rationally knew that for the owl it did not have that meaning. Or, did it? Maybe it did—he wished that he could comfort the poor creature.

He arrived at his home and turned on the lights. Some of the plants that he kept on his porch were the type that bloomed in the fall, such as the lavender asters, whereas others like the blue, white and red petunias flowered practically throughout the year. All were doing well, but at the first sign of frost he would bring them inside so they would not die from the cold.

Now, came the tedious chore of managing the piles of loot. Most of it would fit in the attic, where there was plenty of room. But, first, he made sure that all the curtains were drawn tightly closed.

“Ukulexa, play treble muckn tubyoto.”

“You need to repeat that command,” came the female electronic voice of device that connected him to the internet, including music stations.

“Ukulexa, play michuto makgur pft!”

“You need to repeat that command,” the device repeated.

“Oh, you defective brakrrat!” he faked anger and disconnected his Ulexa from the wall and went to the garage and inserted it inside the trunk of his car. An absurd precaution, possibly, but just to be sure. His knowledge of electronics was not enough to be sure whether it would retain enough power to continue to function.

Trueheart reentered his home, turned on his CD player, adjusting the volume loudly on a Beethoven symphony, the Eroica. He walked up the stairs to where the trapdoor to the attic was located and pulled on the handle, opening the attic door, with the stair automatically descending. He slowly climbed up.

“You can come down, now,” he told the four Cirullis hiding in his attic, expectantly waiting him. “I’ve got all your stuff below. It’s all in piles, I’m afraid,” explaining as he climbed down, followed one by one by the father, mother and their two teenage children. “You’ll have to sort it out, put stuff in the washing machine, and so on. Now you’ll be able to sleep more comfortably. And I can have some of my linen back.”

“Dr. Trueheart, thank you so much for all you’ve done.”

“Derek,” he corrected her. “I told you before, Kendra. Call me Derek.”

“Did you have any trouble?” They all spoke softly to each other, at the request—command, really—of their host. Just in case.

“No. The key was still there and I got everything that was on the list and then some. Preparation was the key in doing it quickly.”

They reached downstairs. “I’ll leave you all to it,” Trueheart said, motioning to their belongings, seeing how eager, how happy, the family became at seeing their things. “You may want to wash some of the clothes,” he called behind him as he walked away.

He returned and reminded them, as he always did, to stay away from the windows so that their shadows from the rooms’ lights would not project onto the windows, even with the heavy curtains as a precaution, since he was the only one supposedly living in the home. Several shadows on a window, or different windows at the same time, would pique the curiosity from busybodies.

As the Cirullis rummaged through their things, Trueheart went to the bathroom to take a shower. After the shower, he dressed and went downstairs to prepare dinner. He could hear the clothes washer doing its job.

He was pleasantly surprised at seeing that the family had quickly cleared out most of the things. He had thought earlier that it would take them hours. They were efficient. That was good.

“Where’s everything, Frank?”

“Kendra stored away the food and she’s cooking now. She’s also washing some clothes now. Kids are upstairs now, arranging the pillows and bedspreads and separating the clothes. They’re using those boxes to store things. I carried the books upstairs, but I don’t know why you brought them. I noted that you have the same books we do.”

“Because I hate lending my books to anyone. Besides, if I left them back there, some of them would have been taken off to be burned.” He paused. “But you all need to read. It’ll help to pass the time when I’m not home. It’ll distract you from the present.”

“Derek, I want to thank you again—”

“Frank—”

“No—let me finish—for taking us in, for sheltering us, feeding us. We know what a burden it is for you, even if you won’t say, and how dangerous it is for you.”

“Frank!” The doctor’s voice sounded irritated. “You’ve said it all before. It’s becoming tedious. And go take a shower. Do it now. You smell bad.”

Trueheart went to the kitchen and found Kendra cooking, happy as could be, as if the menacing world outside did not exist and this was her home. He realized that her demeanor really did lift his own spirits.

“Spaghetti, I see.”

“Is that OK? I’m, sorry. I didn’t think to ask you.”

“It’s good. I was in the mood for spaghetti,” he lied.

“Do you like mushrooms? I was going to add them, but if you—”

“—I like mushrooms.”

He went to where the painting and the Lladró ceramics had been put down and wondered where to place them, so they would be at their best. He chose several spots for the Lladrós and placed them there, further deciding that the living room would be the best place to hang the painting. He would do it later, though, after dinner.

“Kendra said that dinner’s ready,” Derek informed him. He looked refreshed after the shower, wearing a set of fresh clothes that Trueheart had brought over and his hair was moist, though combed.

The five of them sat down at the brightly lit dining table. Kendra had placed her blue and white dinner set on the table. It was a nice change of routine. She went around the table serving the red spaghetti.

“Derek, would you like to—” Kendra asked.

“—You. As always.”

The family closed their eyes and clasped hands with each other and their host.

“Father in Heaven, we thank you for watching over us during this storm, for blessing us with sanctuary and for having such a dear, loyal, friend as Derek. Few people these days would have had the courage and the self-sacrifice as he has. Please bless this home, this family, this friend. And please help our poor country from its satanic enemies. Amen.”

“Amen,” everyone responded. Frank now opened the amontillado and poured it into the glasses.

The couple asked him a constant stream of questions between bites of food, not only about events going on in the country, but especially about the visit.

“Your home will be occupied in a couple of weeks by what I can only anticipate will be the scum of the earth from some pigsty of a country. I only hope that the savages know how to use a toilet. We’ll see. Maybe it won’t be too bad. I hope that they don’t trash your house.”

“You did a good job in collecting everything, Derek,” Kendra changed the topic of conversation to make it less depressing.

“The list you gave me helped. But really, we got lucky. The moment I learned that—that—” here he used an obscenity to refer to Cohen, the only obscenity that they had ever heard him utter since their acquaintance and solely in reference to their fanatic neighbor, “was going to turn you in to the FBI, I knew I had to move quickly. It was sheer luck that I got there first to lodge a complaint against you. I suppose I should have notified you first to give you more time to gather up some more of your stuff, but Frank was at work at the time, anyway.”

“We were lucky we weren’t picked up right away,” Kendra nodded.

“Well, I knew that it would take them some time for them to come arrest you. I have worked in the past in bureaucracies and they are slow to move and like to fill out paperwork. Besides, they have their hands full these days arresting so many people. At least you were able to pack some things to bring over with you. My main worry at the time was that you would not seriously believe the urgency of the danger. It seems that some people just stick their heads in the sand, hoping it will all blow over. Until it’s too late.”

“I never thought, I never dreamed, in my wildest dream, that our FBI would turn into another KGB or Stasi,” exclaimed Frank. “I still have trouble accepting it.”

“It’s a bureaucracy, like any other” Derek shrugged. “The members of bureaucracies are conditioned to carry out any orders from above. The agents that came here did not strike me as the usual ideological hysterics. They were just doing their job, no matter what job they were given. The fanatics, the rabid dogs, were busy elsewhere, I guess.”

“Ve vere jest obeying orders,” Frank said with a dubious accent. “Now … where have we heard that before?”

“Derek, what do you think is going to happen now?” Kendra asked. “And what about the other countries?”

“They’re busy consolidating their power. But about the other countries, I think—”

The doorbell rang, barely heard over the music. The Cirullis instantly stiffened and their eyes widened. Trueheart raised an eyebrow.

“Are you expecting anyone?” she could not help but ask. Trueheart put his finger up to his mouth to his mouth to demand silence.

“No. Never. I hate having visitors. Especially uninvited visitors,” he hissed. The teenage boy got the impression of Trueheart being a coiled rattlesnake.

The doorbell rang again. Frank whipped out his handgun and aimed it upwards ready to use it. Derek looked at him with narrowed eyes and slowly moved his head, side to side.

Frank put away his gun.

I will have a talk with him later about that gun of his.

Their host pointed his finger up in a circular motion, finishing with an upper thrust. The family got up, exited the dining room on the way to the attic. He looked back at the table and became alarmed.

“Wait, stop,” he said in a normal voice and he motioned them back to the table. He pointed to the plate and glasses, then motioned upwards again.

The four of them understood, picked up their plates, utensils and glasses and carried them out.

“Don’t hurry. Don’t spill anything.”

The doorbell rang again as the trapdoor shut closed.

The doctor looked through the peephole into the darkness and hissed softly, chiding himself for doing so, even if there was no one to notice his reaction.

It was Cohen.

He opened the door, arms by his side.

“Hi, guy, I kept ringing the doorbell, I thought you might be out.” He was grinning.

If you thought I might be out, then why did you keep ringing my doorbell?

“I have my music playing loudly. I didn’t hear you at first.”

“That’s Beethoven, isn’t it? You know, Beethoven was really a black man.”

The corner of Trueheart’s mouth barely twitched, but he controlled himself. “So, I’ve heard. What can I do for you?” He spoke in an unwelcomed monotone.

“Well, I noticed a car driving up to your house and wondered if you had received the permission for entry.”

“I did. You will get yours tomorrow, they said.”

“Yeah, I shouldn’t have told you I was going to do it. Oh, well. Anyway, the really important thing was to put those people put away for good. So, when are you going over to their house and grab some goodies?”

“Already done.”

“Boy, you didn’t waste much time! Hope you left something for me.”

“The furniture’s all there. I left a lot of stuff behind. Some of the stuff that I took I’m going to use, the rest I may sell.”

“I hope you left some food behind.”

“I think that there’s some in the refrigerator. You’re welcome to it.”

“Speaking of food, something smells good.”

“My dinner. It’s getting cold.”

“Oh. Sorry. I’ll leave you to it. By the way, did they say whether they caught the Cirullis?”

“No, but I hope they do so soon. I’ll be glad when those types of people are gone.” He forced a smile on his face.

“Yeah, me too. Well, I’ll let you go back to your dinner. See ya.”

Trueheart dropped his smile and closed the door, mentally bringing up the obscenity once more to describe his neighbor, but kept an eye on Cohen by peering through the curtain until his neighbor went back into his home, then the doctor went up and told his guests to return to the table. The food had to be warmed over, of course.

“Killed a perfectly good mood,” he muttered and his guests agreed.

“Frank, do me a favor while she’s microwaving the food. The Third’s almost finished. Would you put it Dvorak’s In the New World in the CD player? Thank you.”

They resumed their dinner and the conversation after it was warmed. Another glass of amontillado helped restore the good mood. During a dessert of canned peaches sprinkled with cinnamon and after further conversation, Trueheart made an observation.

“I have learned in life that nothing is ever permanent. Nothing! Nothing whatsoever. Not in the long run, really. If you look at history, our country, all of mankind in fact, has experienced traumatic events in the past and ultimately survived. We’ll get through this. Somehow, someway, we’ll get through this.”

“We can’t let this happen again, though,” said Frank.

“People don’t pay attention to history, so they keep making the same mistakes,” Kendra observed.

“I think Jefferson said that the tree of liberty needs to be fed with the blood of tyrants. I know whose blood I’d use first,” Frank motioned with his head towards across the street.

“Well!” With a slight smile, Derek playfully slapped the table. “It was a good dinner, Kendra. Thank you. It would have all been better without the interruption from outside, but it was, nevertheless, enjoyable.”

“Kids, help your father sort through the stuff while I clean up. Derek, you go and relax. You’ve done a lot today.”

Everyone got up from the table, feeling good from a full meal.

Dr. Derek Trueheart went out to his backyard for the brisk air. He stood outside, in the darkness, listening for some time to the sorrowful, sad call of the owl until he felt chilly from the cold.

“Yes, we’ll eventually get through this. Sooner or later,” he muttered and went back inside to the warmth.

Armando Simón is the author of When Evolution Stops.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast