The Three-Thousand-Year-Old Treasury of Hebrew, Part 2

Neologisms and Acronyms

by Norman Berdichevsky (August 2023)

Hope against Hope (detail), Renato Guttuso, 1982

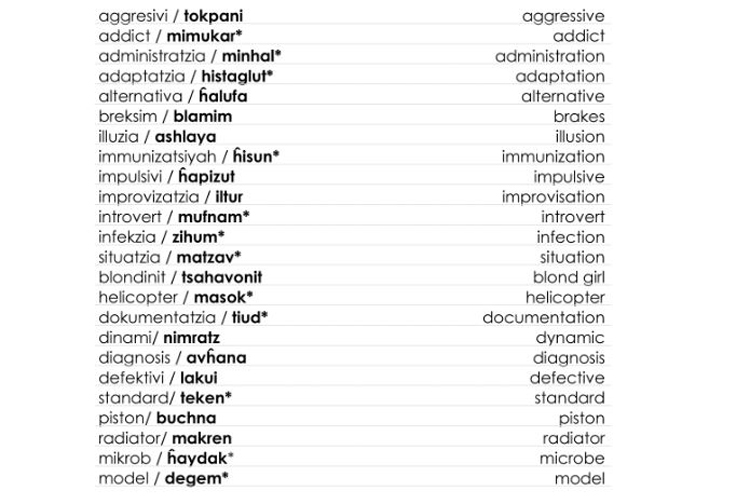

Modern Hebrew has derived much of its contemporary vocabulary from two sources: the one indigenous to the ancient language based on existing recognizable three consonant-letter roots (shown below in bold), and the other, words of foreign origin (called loazi) that resemble English which are easily recognizable by those Israelis who are not intimately familiar with the indigenous sources and have not reached a high level of familiarity with the older classical Hebrew sources.

So, why should anyone need to continue to use “administratzia” in place of minhal, “breksim” instead of blamim, situatzia instead of matzav or “faktim” instead of uvdot?—words that have been in use in journalistic and radio/tv Hebrew for the past 50 years? This way of thinking has led many Israelis to unconsciously prefer the more easily recognisable words with an “international appearance” in everyday speech. For many Israelis of European origin who arrived in the mass post 1948 immigration, installateur comes to mind more readily than sharavrav (the dictionary approved word for a plumber).

This very lenient policy has long term negative consequences as can be seen in the many grotesque street and shop signs that use Hebrew letters to write English or “international words.” The fact that the Academy has more than once issued statements to the effect that while the native Hebrew term based on indigenous sources is “preferable” to words of Loazi origin, it has not tried to combat the many terms which were in common use before campaigns by Hebrew scholars to find more acceptable words using “neologisms” (see list below in bold) which a learned Hebrew speaker could recognize from classical archaic Hebrew words denoting a “root concept.” It was left up to the speaker as a matter of choice. Occasionally one can even see different words, one of which is pure English (such as center) and the Hebrew equivalent (mercaz) as in an ad for ‘Galilee Investment-Mercaz Center” (both mercaz and center refer to the same thing).

The following word pairs of diverse origins are only a few examples of this “dual vocabulary,” and reveal the diverse heritage of Modern Hebrew. The preference of a speaker for one or the other has been a matter ultimately decided by popular opinion regardless of the official judgments of the Academy.

The more sophisticated “indigenous” words marked in bold with an asterisk* appear to have won out in most popular usage since they appear frequently on public signs and are in constant use by the mass media. This is a dynamic situation and Hebrew speakers who return to the country after an absence of a decade or more are sometimes surprised to discover that words they considered as part of everyone’s common vocabulary are no longer regarded as such.

FOREIGN / Neologisms ENGLISH

(LOAZI/indigenous origin)

Many of the words based on original authentic ancient Hebrew roots appear to have won out because they appear so frequently on public signs or instructions, or at government facilities. The use of foreign-origin (loazi) words (immediately apparent in meaning to English speakers, such as situatzia, improvizatzia, defektivi, standard or mikrob) is common among those with little previous knowledge of Modern Hebrew who learned the language after arriving in Israel and the younger generation who are not well-read. This is similar to the decline in literacy due to the preference they have for the popular culture of television, social media and the movies.

This is all the more ironic since the neologisms on the list were in common usage due to the popularity of enthusiastic Hebraists who felt they were carrying on the work begun by the pioneer of developing a modern Hebrew vocabulary, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda. There are thus many such word pairs commonly heard today. Uninformed critics of modern Hebrew often make the mistaken assumption that it sounds like a crude form of English or Esperanto. They do not understand that Modern Hebrew has its own corpus of a polished modern vocabulary that is traceable to indigenous roots, the formula devised by Ben-Yehuda that several generations of linguists have followed to expand the Hebrew vocabulary.

From the 1880s to World War II, new words of Hebrew origin (or Arabic or Persian indigenous to the Middle East) were coined and the public encouraged to use them instead of the internationally recognized words that resemble English or have typical German or Russian suffixes. Today, many readers with a minimal grasp of Hebrew vocabulary and not familiar at all with the written language can much more easily relate to the words of foreign origin. This explains their persistent usage not only in the popular press, comic books and cheap novels but also among politicians who cater to the “lowest common denominator” in their speeches.

Modern Hebrew’s Massive Use of Acronyms

Another novel and growing trend of modern Hebrew is the growing use of acronyms utilizing the consonants of the original classical Hebrew. Due to the absence of vowels in most books and the propensity of Israelis to make up acronyms, this spoken short-hand Hebrew is a characteristic feature of the modern language. Acrnyms are formed from the initial letters of other words and pronounced as if they were a single short word instead of speaking out the individual letters. as when we speak of N-A-T-O, and U-N-E-S-C-O.).

Due to the absence of vowels in most books and the propensity of Israelis to make up acronyms, this tendency is a growing feature of Israeli Hebrew. Most of acronyms are not found in any dictionary and are used only in the spoken language before text-messaging and e-mailing gave birth to these now ubiquitous linguistic shorthand terms. Jews are not just the People of the Book. Israelis speaking Hebrew have become the People of the Acronym.

Observant Jews or those who visited the graves of their ancestors were sure to observe two abbreviations that were nearly universal on tombstones and inscriptions honouring the deceased. These were

Z’’L (Hebrew letters zayin and lamed) that stand for: ZiCHRono l’bracha (for a man] or zichronah for a woman), …l’bracha meaning respectively, His or Her memory; meaning. “May his or her memory be a blessing.” It usually appears in parentheses after the name of a person who is deceased.

P”N (Hebrew letters peh and nun ) which stand for: Po niKBaR represented by the Hebrew root letters, the consonants K-B-R having to do with burial; the peh and nun standing for “here lies” or “here is buried.”

In traditional Hebrew and Aramaic, many abbreviations appear on Jewish gravestones and in correspondence, and books. However, acronyms were not used in earlier forms of Hebrew but have become very common in the modern language. One exception is the acronym traditionally used for Hebrew Bible, known as … TaNaKH which stands for: Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim; known in English as Torah (also the “Five Books of Moses”), Prophets and Writings. Ta-NaKH is the way Jews refer to the Old Testament. In Modern Hebrew, there is a massive and growing vocabulary of acronyms, usually wholly unknown to those who do not reside in Israel and are not fluent speakers. Some new words were formed by creating new words using the first consonant letter from constituent parts of the word. The classic example is the word for cutlery, SaKuM created from joining the first letter of the words for Knife (Sakin), Spoon (Kaf) and Fork (Mazleg).

Thus, in Hebrew we find such acronyms that join fragment syllables from two different words as:

- “Motz-TZash” that stands for MoTZei Shabbat meaning Friday evening after Shabbat officially ends. Stress on second syllable.

- “Sof-Fash” for the weekend; SoF-SHah-VOO-ah, literally the end of the week. Stress on second syllable

- “Tza-Hal” that stands for: Tzava ha-Hagana L’Israel; Pronounced: TZaH-hal; meaning The Israel Defence Forces (IDF). Stress on first syllable.

- “Ĥalat’ in Hebrew—for the terms “Ĥofsha L’lo Tashlum” —or in English—Leave of absence without pay. Stress on second syllable.

Students of Biblical Hebrew are totally unfamiliar with dozen of such acronym expressions commonly in use today. Israel’s major international airport is frequently referred to is the acronym form based on its full official title as Namal haTiufah Ben-Gurion. “NaTBaG, ” with stress on first syllable.

What does NATBAG stand for?

Ben Gurion Airport (Hebrew: Namal haTiufah Ben-Gurion), commonly known by its Hebrew acronym as NTBG Natbag (נתב״ג), is the main international airport of Israel and the busiest one in the country. The road sign below indicates you are on the road to NATBAG. Don’t worry you are on the right road if you are heading to the airport.

If you are travelling to RiSHon-Le-Zion, it is a lot easier to simply say RaSH-LaTZ, with stress on second syllable. Such new “words,” frequent expressions and the names of towns which are pronounced as acronyms number in the hundreds (possibly thousands) and are a lively part of every Israeli’s vocabulary. They are frequently used in short advertisements in the written form and are often used in verbal speech.

The most entertaining one I came across embracing an entire phrase of several words forming a full sentence on my last visit was This is your problem! “Zabashka” for zot ha baiya shelcha. Whatever classical linguists may say and argue, this tendency appears unstoppable. In order to get by in modern conversational and informal written Hebrew, knowledge of dozens of these acronyms is now essential! Why are they such a growing feature of contemporary speech in Israel? They save time in a society which is always in a rush. The country has often depended on rapid mobilization of its military forces to meet immediate threats. They also reduce the need to speak using difficult grammatical constructions, a fact which in part explains why they are so much more popular among the younger generation which regards them as “cool.” Apparently, there is a special satisfaction for a teen to use zabashka as a put-down towards one’s father or friend.

P.S. To New English Review’s Dedicated Editors, Staff, Avid Writers and Readers:

Having “celebrated” my eightieth birthday in May and reviewing my work in submitting monthly articles since March, 2006, I have decided to make this month’s submission my last. I think it is time for new contributors to have their say. I believe that I was given a unique and generous opportunity to express myself on many issues and debates about which I felt passionate and wish to express my appreciation for the dedicated work of Rebecca Bynum and Kendra Mallock for their efforts over so many years to keep New English Review alive and kicking on the internet and defying the many attempts to sabotage the journal’s independent voice. I also owe a debt of gratitude to all my colleagues and the previously unknown unknown readers who sent in reviews commenting on my work encouraging me to continue. It is certainly due to them and the new advertisers they attracted that New English Review must be counted as a great success.

Table of Contents

Norman Berdichevsky is a Contributing Editor to New English Review and is the author of The Left is Seldom Right and Modern Hebrew: The Past and Future of a Revitalized Language.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast