The Thrill of the Chase: Philately

by John Henry (June 2020)

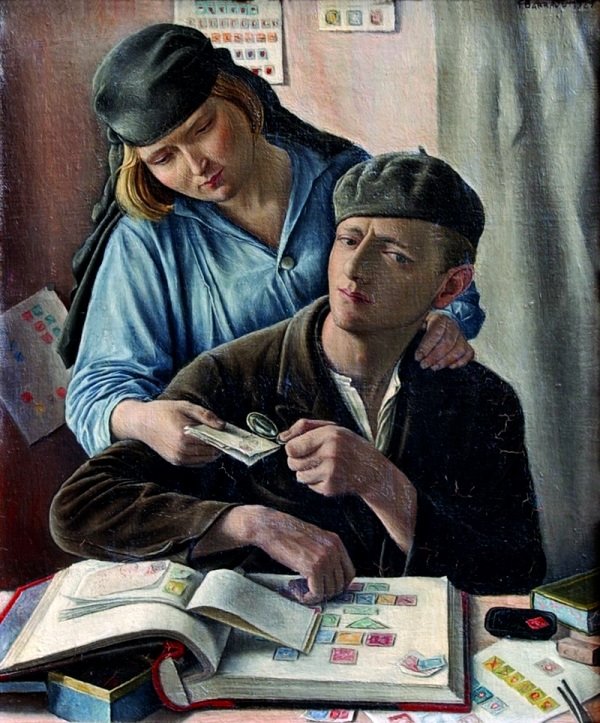

Le Philatéliste, François Barraud, 1929

It started as a cache of stamps carefully torn or cut from family correspondence and from friends who thought I’d be interested one day. Mom had held many for years hoping one day I would want to collect them. She would show me a few every now and then.

It seemed like the medium on which the stamps were affixed was just as interesting as the size, color, and graphic of the stamp itself. I liked the feel and look of the envelope. In those days in Greece and Turkey they used a light blue colored paper stock that barely obscured the writing stuffed inside. The envelopes seemed compact and unlike our modern standard.

The penmanship was also of great interest, mostly using ink pens in either blue or black. They were always neat and easy to read. There was a painstaking aspect about that, with a few globs quickly blotted off. Americans tended to use ball point pens. Some were even addressed using a typewriter. There was a postal impression as well which indicated at what time it was posted and from which city.

I started reading a little on how to keep, handle, and store stamps.

First, one had to wet the stamp and envelope and then gingerly peel back the stamp, then dry it very well between cotton or paper towels. It was like a medical procedure. If you were too anxious you would tear the stamp.

The first stamp book I had was bought at a local store that offered notebooks, pencils, pens, watercolors, cut paper, and formatted writing books for the schools. It was fascinating to see what was available.

This particular stamp book had a clear strip of plastic glued at the bottom that ran horizontally across cardboard pages front and back. You simply decided where to arrange stamps of different countries or by subject and start placing them delicately into these rows. They were well protected and easy to maneuver.

There was a sort of special tweezers implement with rounded ends so that your fingers would not stain the stamp with perspiration or grease.

The Americans had a different method: you would buy huge albums that had nearly every stamp minted by hundreds of countries. Each page illustrated the stamps per year. You merely had to spend the rest of your life collecting every stamp illustrated and then when you had finished you won. I didn’t care for the little glued strip that was used to affix the stamp to the album.

.jpg)

I was an avid comic book reader in the mid-60s and had a paper route even in Izmir. I noticed adverts in the back of the comics and wrote off for a ‘free’ group of stamps that arrived within about two weeks from somewhere in the United States.

It was like having a birthday. Here I had in my possession dozens of stamps from countries I had not even heard of. Different shapes, colors, currencies, subjects, etc. This was how the stamp companies got a hold of you. Free stamps led to stamps paid on approval. Every month a stash of stamps would show up in the mail and one had to decide what to keep and what to buy.

This was probably how I first learned how to negotiate with my parents. You had about a two-week period in which to make your selection and keep/buy what you wanted or send back what you did not. This went on for a few months and finally it was overwhelming. I had bought two or three more stamp books and they were getting filled with wonderful stamps.

There were stamps about famous people, inventions, memorials, butterflies, fruit, and animals. For a youngster, this opened up one’s mind to the world. You would wonder what Magyar meant and then go to a dictionary and then to an atlas to find the country. The entire endeavor was educational and that is probably why my parents obliged for so many months.

There were a few levels of sophistication involved. You could buy blocks, first covers, specialize in a few countries, and within a country a particular subject. Some people dealt only with stamps in a range of years, etc. I just wanted anything I could lay my hands on.

One day an older friend and the son of our landlord who was studying architecture in Paris took me to the main bazaar in town which meandered endlessly it seemed through a series of crooked, ancient roads from the port stop of Konak in Izmir, a trading hub for hundreds of years. After about 20 minutes we darted left into a small alley and in the shadows was a small shop. Inside, an elderly man with glasses smiled and shook our hands and proceeded to show us stamps he had for sale in glass showcases. I bought a few and we thanked him and returned home.

A couple of weeks later, I decided I wanted to find this shop and asked to go by myself. I was about 13 or 14 and we had been living in the country for about six or seven years. I knew a few words and felt somewhat confident I could find this small hidden shop again.

Mom handed me a few coins and instructed me to behave, not get involved with anyone, to be safe and to come back immediately.

The first step was to get to Konak, about five miles away from our apartment. I flagged down a jitney and said ‘Konak’, and after about 8 stops I paid the driver and walked out into the bright square. There were buses, taxis, and it seemed a thousand people walking around on a Saturday morning. The Konak clock tower was a sort of visual landmark and that comforted me. Just across the plaza was the entrance to Kemeralti Bazaar.

I remember watching Charade when it came out in 1963 (a couple of years earlier) and I was astonished that the entire drama concerned a couple of stamps that were worth millions. The child in that movie was coached to find the seller of that envelope and stamps and, like him, I was now going to enter a no-man’s land trying to find the proverbial needle. The time was about 11:30 and the crowd was pressing. I was of average height for my age and didn’t look too out of place until I opened my mouth.

I think my friend had given me the address but that wasn’t a big help. There was no GPS, no map, just an American kid milling through hundreds of people who knew exactly what they wanted and where to get it. And who didn’t care a whit about me.

It was getting hot now and people were pressed on each other, but things were quite civilized. There was no hawking of goods. Well, just a bit. There were shops selling children’s clothing, women’s personals, headkerchiefs, rugs, coats, shirts, shoes, slacks, socks, a few gold shops, plastic wear, beads, some toys, chairs and tables, flowers, seasonal nuts, fish, fruit, soap, cutlery, embroidery, plates and glassware, all mixed together with no apparent logic. The logic was that they were there exactly every day at the same location for years. And everyone knew where to go to find anything.

My head was swimming with colors, odors, shapes, people, tarps stretched over the street, the sound of backgammon down an alley, the smell of cai tea, and herbs, the call to prayer from a mosque. I was bumping, twirling, dashing, looking here and there, looking for telltale signs of the stamp shop and feeling lost. The sun was casting sharp shadows and brilliant light against shade and darkness. I was dizzy but invigorated. I was almost hallucinating.

It was a fabulous notion. Lost. I was possibly lost in a strange land with only a feeble chance of returning home. I was drunk with the notion that I was in the best adventure I had ever undertaken. I didn’t want the moment to pass. Part of me was shaken, the other engaged this peripatetic pleasure and wanted to hold onto it.

Who knew what would happen to me? Did I have enough money for food or a soda pop? Would I be able to explain to police who I was and what I was doing, where I was going, from whence I came? Would they find me alive or exhausted? Was I going to be robbed or stolen? My heart was pounding, my mouth parched.

And then I saw it. The dark narrow street to the left. It had to be on the left. It could only be on the left. And I darted into the alley looking feverishly for that small wooden faced shop with a window offering up a glimpse of something so esoteric as a collection of stamps. Lazy ferns and an olive tree were outside. I could see men smoking hookahs across the way in a small coffee shop.

The word for stamp is ‘pul’ in Turkish. I went inside and there was a small bell over the door. The proprietor met me as before and directed me to his latest group of stamps. It was quiet and still. The din of the bazaar was out of my mind and I concentrated very hard. I had about three dollars’ worth to spend and I did my best.

Smiling, I paid the man and he put the stamps carefully into a sort of waxy envelope. I said ‘tesekkur ederim’, meaning thank you, and walked back into the din of the market.

I immediately traced my way back to Konak, flagged down another jitney and made my way home.

Dad treated us to great vacations starting from Izmir and Ankara and driving in our 190 Benz through Bulgaria, then Yugoslavia, Austria, Switzerland and Germany. We went on either to Italy, France, or Belgium and back. We drove through Liechtenstein once or twice. At every stop in a major city, Mom or Dad would give me some of the local currency to buy groups of stamps at the city center post office. I had something to examine for hours and with which to get lost mesmerized by the colors and shapes as we drove through the lovely country sides and cities.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Commercial Web Residential Web 7491 Conroy Road, Orlando, Florida 32835 407.421.6647

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast