by Fred McGavran (September 2022)

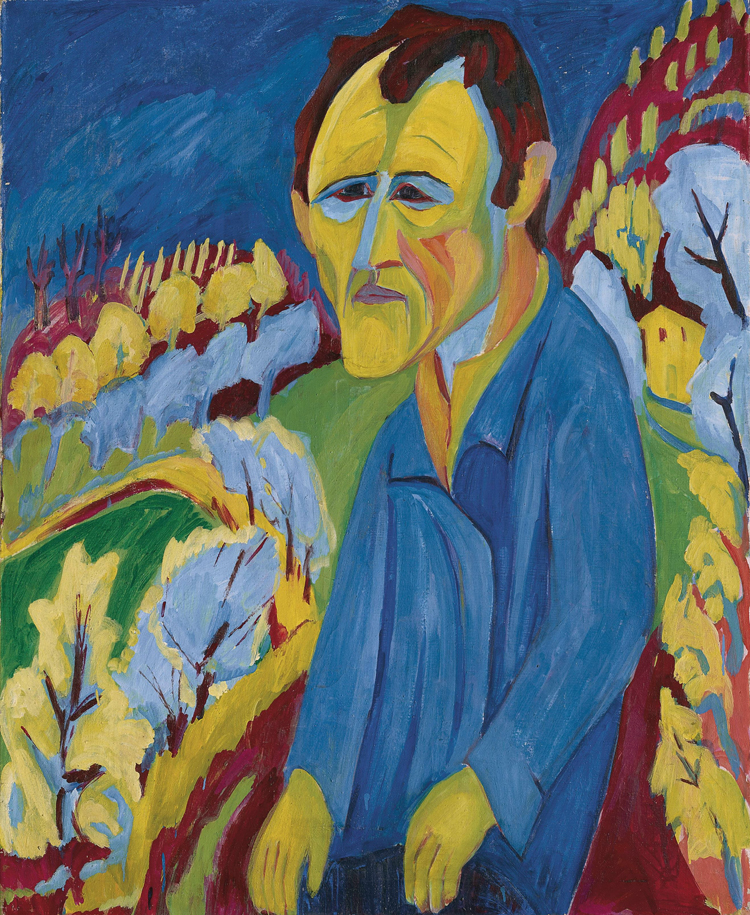

Self portrait in landscape, Hermann Scherer, 1924-26

What’s it going to like being dead, Edward Mowbry wondered the morning after he died. Death itself had come so suddenly and with so much excitement he was still reeling from the experience. Awakened in the middle of the night by terrible chest pains, he had pressed his pendant for help. Suddenly emergency medical technicians burst through the door, pounded on his chest, laid him on the floor and gave him an electric shock that flipped him out of his body. It was odd floating over them as they tried to bring him back. When they finally gave up, they put his body in a plastic bag and wheeled it away.

The continuity between life and death can prevent an easy transition. When Mowbry went out of his apartment, there was a white rose in a glass vase on the table where his newspaper should have been. In the iconic language of his retirement community, a white rose meant the resident had died.

They move quickly, Mowbry thought. I’ll bet people will drop by to commiserate.

No one dropped by.

Uneasy thoughts from long ago Sunday school classes about what to expect after death returned to trouble him. If his teachers had been right, he would have been in a court far grander than the huge mahogany-paneled courtroom where he had once testified to whatever was necessary for his company to win a stock fraud case. In the celestial court, however, he would be the defendant, and God would be the prosecutor, judge and jury. Mowbry shuddered. What could he say to explain his life? At least I’m still here, he thought. No summons yet for me.

I’d better check to see if they’ve notified the kids, he said to snap himself out of it. “The kids” were his older daughter Lisa and younger daughter Carol. Mowbry drifted down the hall to the elevator.

He nodded to another old man who was watching the lights over the door track the elevator’s slow rise. Seeing the other man’s mask, Mowbry remembered he hadn’t worn his, a violation of management’s corona virus protocol. I won’t need those anymore, he laughed.

“Takes forever, doesn’t it?” Mowbry said, but the old man didn’t answer.

When the doors finally opened, Mowbry followed him into the elevator for their slow descent to the first floor.

He stepped out of the elevator ahead of his indifferent companion. Several old women were crowded around the receptionist, talking through their masks in brittle voices about happy events that may never have happened. Not wanting to wait until the group thinned out, Mowbry decided to return to his apartment. The light over the elevator door said it was still on one, but when he pressed the button to open the door, nothing happened. I may as well take the stairs, he thought, although he had never taken the stairs before. So he passed through the door into the stairwell and floated upwards without the stabbing chest pains that usually accompanied exertion.

Maybe dying isn’t so bad after all, he mused. Mowbry had a sardonic sense of humor most people didn’t share.

Styrofoam boxes were on the little tables outside all the apartments but his, still marked by a single white rose. The rose had started to droop. How long have I been gone, he wondered looking at his wrist. His Omega with the time and date wasn’t there. Did I forget to put it on this morning? Was something playing tricks on him with time? What use was time, now that he had transitioned out of the space-time continuum?

I’m not really hungry, he thought continuing down the hall. He hated eating off Styrofoam anyway, but after the virus struck management forbade eating in the dining room. Now everyone had to eat by themselves in their apartments, which for Edward Mowbry nearly made up for the containers and plastic utensils.

The door to his apartment was open. Now what the hell, he thought.

“God, the place stinks!” his older daughter Lisa was saying as he entered. “I thought they were supposed to keep it clean for him.”

She was standing in the kitchen beside a pile of Styrofoam boxes oozing their contents onto the linoleum floor.

“They kept saying he wouldn’t let them,” his younger daughter Carol said. “I don’t know what we were supposed to do.”

Like their father, they weren’t wearing masks.;

“He must have gotten most of his calories from this,” Lisa exclaimed, touching a paper bag full of empty bourbon bottles with her toe. They were both wearing designer jogging suits and bright new athletic shoes as if headed for the gym for a few minutes on the elliptical machines before settling down to diet cokes.

At college, Mowbry had replaced compulsory Sunday services at his parents’ church with hangovers. Finally married and settled down, he devoted Sundays to golf and football. After the girls were born, he let them follow their own religious inclinations, the only aspect of their lives he did not try to control. They did not develop any religious inclinations.;

“It’s my goddam life,” Mowbry yelled at them.

They continued to ignore him and opened the refrigerator with renewed outbursts of shame and horror.

Then it occurred to him that he might be condemned to spend some quality time with his daughters, something that had never much interested him. No, he reasoned. That can’t happen. His Sunday school teachers had preferred an eternal Protestant hell to a temporary Catholic purgatory.

“We’ll have to get the boys in here to clean it out,” Carol continued.

“The boys” were her adult sons Larry and David, both doubtfully employed staring at computers eight hours a day in return for just enough money to drive oversize pickup trucks and live with second wives and blended families in the suburbs. They were the last people Mowbry wanted rummaging through his belongings.

“If Mother was still here, she’d just die,” Lisa said in the same superior tone that his wife Janet had used so often with him. Lisa’s adult children had moved to opposite corners of the country as soon as they could to get away from each other and from her.

“Thank God she’s not still here!” Mowbry cried.

Janet’s death had been one of the great liberating events of his life, like the day he was discharged from the Navy or retired from the company. How naïve he had been thinking four years in college, three in the Navy, or forty at the company were long times. Fifty-six years with Janet, now that was a long time, and their final separation had not come easily, at least for her.

She didn’t make a lot of noise when she had her stroke. She just said “Oh!” and crumpled to the floor beside their bed. Mowbry had trained himself to stay asleep when Janet got up in the morning to go to the bathroom, but the drama of a fall awakened him.

“Janet?” Mowbry called. She had disappeared. He stood up and walked around the bed.

She was lying between the bed and the wall in a slowly spreading pool of urine. Her eyes were open.

“Janet?” Mowbry repeated.

She had an expression of teeth-clenching horror.

The first minutes after a stroke are critical for the patient’s recovery. Mowbry stepped back. She wasn’t looking at him. She was looking at something behind him so frightening that it froze her features. Mowbry went into the bathroom, rinsed out his mouth, and shaved. When he returned to the bedroom, she was in exactly the same place. The horror in her eyes had changed to a desperate plea for help. Mowbry returned to the bathroom, had a bowel movement, showered, and got dressed. He didn’t look at Janet again before he left for breakfast. If he got to the dining room early enough, he could get a reasonably decent omelet before the cook was overwhelmed with other orders.

After breakfast, a second and then a third cup of coffee, and a conversation with an old lawyer friend about municipal politics, he returned to the apartment. Janet’s eyes had rolled up into her head. Mowbry called the nurse and told her he’d just found her collapsed on the floor.

“Do you think it’s a stroke?” he asked trying to contain his excitement.

The nurse called 911. The one thing Mowbry regretted was leaving her Living Will behind when he rode with her to the hospital. The emergency room doctor wouldn’t take his word that she had declined “heroic measures.” After ten touch and go days in the hospital, during which Mowbry had to endure the whining and bawling of his daughters, she was returned to the skilled nursing unit alive but unresponsive to anything other than an occasional bed sore.

Mowbry blamed himself for not waiting until lunch to call the nurse. To spare his nerves, he limited himself to a brief weekly visit “because seeing her is almost too much to bear.” Self-recriminations linger with age. That’s when the bourbon became a constant. Janet died nine months later.

Lowry looked around his apartment, surprised he had not been swept up to answer for those events. They must have gotten it wrong in Sunday school, he thought, relieved to still be there.

Lisa and Carol interrupted his reverie by moving their scene of operations into the living room. Mowbry followed and sat down on Janet’s settee, the one her mother had so loved and he had so detested for decades. Why hadn’t he called Goodwill for it after she died?

“Have you ever seen so many Wall Street Journals?” Lisa exclaimed pointing to the pile beside his reclining chair.

“You’ve never minded asking me for money,” Mowbry snapped back. “If I didn’t follow the market, where would you be?”

“And what about Mother’s jewelry?” Carol said, going into the bedroom and opening the dresser drawers. “My God. Do you think he ever bought new underwear?”

“Maybe he put the jewelry in the safe deposit box,” Lisa called.

“We’ll never find the key in this mess,” Carol said.

“It’s in the desk, but I’m not going to let you have it,” Mowbry snapped. He was ready for a bourbon on the rocks.

They didn’t pay any attention to him.

“And what about the funeral?” Lisa asked, sitting down in the desk chair and starting to rummage through the drawers.

“We can’t have a church funeral because of the virus,” Carol replied.

“Nobody would come anyway,” Lisa said.

“What the hell do you mean by that?” demanded her father.

“Look! I found it!” Lisa said holding up the safe deposit box key. “Wasn’t he buying gold coins in case the economy collapsed?”

“Oh, thank God!” Carol exclaimed, returning to the living room. “It must be a month since he changed the sheets.”

“We have a lot to do,” Lisa said, her usual signal to disengage and deal with the problem another time.

“Do you think we should have him cremated?” Carol wondered, sitting down in her father’s favorite chair in front of the TV.

“It’s cheaper, isn’t it?” her sister responded.

“What’ll we do with the ashes?”

“I suppose we could divvy them up,” Lisa said thinking out loud.

“I don’t want any.”

“Neither do I.”

For a moment the girls were silent, imagining their dead father crackling into cremains in the undertaker’s oven. Growing up with an irascible tyrant had left indelible marks on them.

“You know he’s got all that bourbon,” Lisa began. “Would you like something?”

“It’s gonna be a long day,” her sister replied.

“Now just a minute!” Mowbry exclaimed, getting up from the settee. “That’s my bourbon and my safe deposit key and … ”

She walked past him as if he wasn’t even there. Being dead had its disadvantages, he was beginning to understand.

They left for the bank with the key after talking themselves into a second drink.

It’s like I don’t even exist, Mowbry fumed. Furious with himself for letting them get away with the safe deposit key, he went into the bedroom to see if Carol had taken his gold cuff links or the gold-rimmed Omega watch he had bought in Hong Kong while he was in the Navy. Carol had left the top drawer of his dresser open, but his jewelry box was closed and he couldn’t open it.

Damn it, he thought. All those years of giving them everything they ever wanted and they treat me like this. He was turning to go to the kitchen for a drink when he smelled urine, like the urine when Janet collapsed after her stroke.

Now what the hell, he thought. I had the damn carpet replaced. He looked around to see what was causing the smell and there she was again, crumpled between the bed and the wall, staring up at him with an expression of infinite loathing.

People don’t come back from the dead, he thought. Time can’t just reverse itself and rerun the worst parts of the past.

“Janet!” he cried. “You’re dead. Go away!”

She just lay there staring at him. The urge for a drink was stronger than he had ever experienced, but he couldn’t move. He couldn’t sit down. He was hovering horizontally over her, smelling her, unable to close his eyes, unable to turn away.

What the hell is going on, he kept thinking. How long do I have to endure this?

Voices from the living room interrupted him.

“Do we have to carry this crap out?” Larry said to his mother.

“Just do it!” she snapped.

Thank God, Mowbry thought. They’ll see Janet and take her back to wherever she came from. But they left her there the same as he had the morning of her stroke. Other voices mingled with his daughters’. Representatives from the boys’ blended families had accompanied their putative fathers to share in dividing the spoil. None were wearing masks.

Sometimes they found something they could eagerly quarrel over, like his class ring and the gold cufflinks he had worn at his wedding and the studs for his tuxedo shirt.

“Like wow! This gold shit is awesome!”

Most of the time they were silent in the face of objects too dated for their imaginations, like the Zippo lighter from the Navy with his old ship embossed on it.

They were so excited by the gold case for his Omega that they took it to their fathers.

“It stopped ten days ago,” one of them complained, pointing to the time and date. “How do you make it work?”

“You got to wind it, cretin,” Larry responded taking the watch.

“Who gets it?” another blended son demanded.

“I do,” Larry replied putting it on. “I ought to get something for giving up a weekend to clean out his shit.”

It took them the whole day to empty the kitchen and the living room. All the while Mowbry hovered face down over his stricken wife, as lonely and despairing as a self-conscious proton in an expanding universe with all the galaxies around it receding. When they returned the next day for the bedroom furniture and the oriental carpet in the living room, Lisa and Carol pulled out all the drawers and threw his and Janet’s underwear and stockings and socks into garbage bags before stripping the closets.

“I can’t believe he kept Mother’s dresses,” Lisa said.

“They won’t take his suits at the thrift shop,” Carol said. “All the pants have pleats.”

“For God’s sake, get her out of here!” Mowbry screamed. What kind of daughters would leave their mother lying on the floor with her helpless husband hovering over her?

“It smells like urine in here,” Lisa said, looking at the floor between the bed and the wall where Janet had fallen.

“It probably got into the floorboards,” Carol said. “Dad never had much of a sense of smell.”

“I do too!” their father cried.

In the living room Larry and David were arguing over the oriental carpet.

“I’ll bet I could get a few thousand for it on eBay,” Larry said.

“It was my mother’s,” Carol said. “We have to keep it in the family,”

“I can use it in the rec room,” David volunteered. “The kids need something to lie on when their friends come over.”

David had to scream at his offspring, real and blended, to help him carry the oriental carpet to his truck. Lisa and Janet and the rest followed them out of the stripped apartment, leaving Mowbry alone with Janet.

Her expression was changing from fury to malignant satisfaction, like the spouse of a murder victim settling back to await closure as the executioner injected poison into the killer’s veins. The worst part was he couldn’t look away.

Yes, Janet! he thought. Maybe she can get me out of here.

“Janet,” he began.

Janet stood up and smiled.

“What’s going on? I thought you were dead.”

“We’re both dead, dear.”

Mowbry decided to go along with it to see if she could help him.

“So why are you standing around as if nothing ever happened, and I’m stuck here like a bug on a pin?”

“Things are different now.”

“Isn’t time to go?” he said, hopefully in the same voice he had used at their wedding reception.

Janet kept smiling, and for the first time in his ordeal Mowbry could smile, too. Without speaking she tip-toed around him and went to her closet. Her still-hovering husband was able to turn his head just enough to see her put on her favorite party dress and step into heels.

“I thought the girls took all your things,” he said.

“Oh no, dear. I get to have anything I want now.”

“That’s great,” he said to humor her. “Let’s get out of here and have some fun. Where are we going?”

“I’m going to a party at Mother’s.”

Mowbry tried to straighten up, but he couldn’t move.

“But what about me?” he demanded. “We always went everywhere together.”

“You’re staying here.”

“But that’s not fair.”

She walked to the door, swished her dress behind her to show off her figure like she always did before they went out, and turned around to face him.

“You’re not in charge anymore, Edward,” she said.

“What are you talking about?”

Mowbry heard her heels crossing the bare living room floor.

Impossible, he thought. Ghosts don’t put on party dresses and heels to go to parties at their dead mother’s.

“But what about me?” he repeated. “When can I leave?”

Her heels clicked back to the bedroom door and she looked in. He hadn’t seen her smile like that since the minister had said, “You may kiss the bride” at their wedding.

“You can leave when I’ve forgiven you,” she said.

He heard her heels clicking away and the door close.

Fred McGavran is a graduate of Kenyon College and Harvard Law School, and served as an officer in the US Navy. After retiring from law, he was ordained a deacon in the Diocese of Southern Ohio, where he serves as Assistant Chaplain with Episcopal Retirement Services. Black Lawrence Press published The Butterfly Collector, his award winning collection of short stories in 2009, and Glass Lyre Press published Recycled Glass and Other Stories, his second collection, in April 2017. For more information, please go to www.fredmcgavran.com.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

One Response

this.