Think Back Yesterday: The Education of Darryl Pinckney

by Kevin Anthony Brown (November 2023)

Darryl Pinckney, 2018

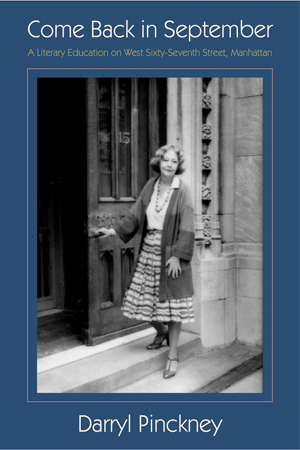

Come Back in September is the oral history of Darryl Pinckney’s literary apprenticeship under Elizabeth Hardwick. A group portrait in eight parts, with Pinckney as participant-observer hovering sometimes about the periphery, sometimes at the center, this book succeeds on many levels: as a portrait of Hardwick and her friendship with New York Review of Books editor Barbara Epstein; as eye-witness account of the cultural history of New York c. 1973-1989; and as self-portrait of Pinckney as he comes of age as author. Come Back in September complements Pinckney’s work in other genres, and chronicles his life in relation to that work.

1. On the Red Couch

Broadway scimitars through Upper and Lower Manhattan, slicing thirteen miles from 220th Street at its northern handle to the Battery at its southern tip. The number 1 train, the Broadway local, stops at 66th Street. Maybe he didn’t have the $0.30 in his pocket a subway token cost. Maybe he needed that money for something else. All we know is that poet and short-story writer Darryl Pinckney walked 50 blocks, that first time, layered in thrift shop sweaters, to visit Elizabeth Hardwick in her home at 33 West 67th Street.

Matisse created a series of Fauvist odalisques reclining on an iconic red couch, Le Canapé rouge. Hardwick’s living room—large, imposing as an opera set—is a stage dominated by the red couch. It forms the mise en scène where recurring characters come and go, where “a topic of strenuous debate” will be dramatically taken up, then dropped. The red couch has heard Flaubertian “quips, puns, double entendres, compliments, and off-color remarks,” overheard scandals long since passed into literary folklore.

Matisse created a series of Fauvist odalisques reclining on an iconic red couch, Le Canapé rouge. Hardwick’s living room—large, imposing as an opera set—is a stage dominated by the red couch. It forms the mise en scène where recurring characters come and go, where “a topic of strenuous debate” will be dramatically taken up, then dropped. The red couch has heard Flaubertian “quips, puns, double entendres, compliments, and off-color remarks,” overheard scandals long since passed into literary folklore.

Members of Hardwick’s circle include Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell, Mary McCarthy, Adrienne Rich, Susan Sontag, Edmund Wilson, among others.

All that riding around Nabokov did on public transit, note cards at the ready, listening, writing down dialogue as if he were George Bernard Shaw—it simply doesn’t work, Wilson sermonizes.

Mary McCarthy advises against young writers’ wasting editors’ time and taxing their patience with short stories and novels. Young writers should learn their craft by reviewing others’ fiction—on the job training. Only solution to the problem “how does this work?” or “why isn’t this working?” is to get under the hood; disassemble and rebuild the engine, bolt by nut. Besides, it’s steadier work, more likely to get published. You might even get paid. Here: go read Edmund Wilson’s New Republic essays. Pinckney says it was Patriotic Gore, quite as much as Notes of a Native Son, that opened his eyes to Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Susan Lee Sontag, brightly wrapped in turtleneck, wreathed in cigarette smoke, has gone days without sleep. Because she’s been up all night smoking, reading, writing. Impairment comes in forms other than alcohol. Sleepless nights can zombify you.

“Kleenex. Where’s the Kleenex?!”

The Kleenex is in her hand.

After breakfast, Sontag walks smack into a wall—the Berlin Wall.

Lowell, shuttling in and out of mental hospitals between bouts of mania, raved that Mein Kampf was his favorite book. But there are traumas of mental illness in Pinckney’s own family. His sister suffers from schizophrenia, her psychotic breaks treated with electroshock therapy. The word “shame” recurs as Lowell describes his feelings about past manic episodes. So, Pinckney’s portraits of Robert (“Lithium Cal”) Lowell are tenderly sympathetic. “I go on typing,” Lowell says, in order “to go on living.”

Presiding over it all was Hardwick herself. The red couch was part literary salon, part writers’ workshop. Hardwick and her friends were sounding boards for doubts each might have about what to write or how to write it. For Pinckney in the 1970s, the red couch became what the Algonquin Round Table had been for actors, critics, writers and wits of the 1920s. Such was Pinckney’s introduction to literary New York.

***

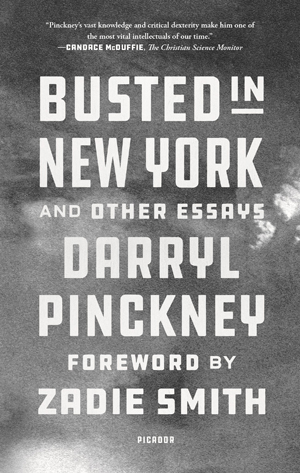

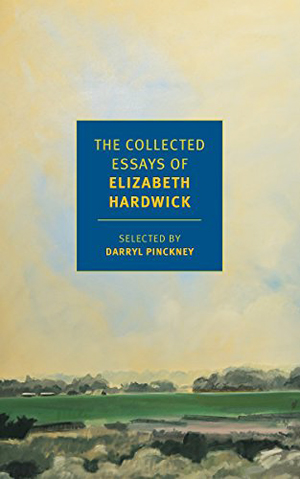

Writing and writers seemed glamorous to Pinckney, the New York Review of Each Other’s Books radically chic. Yet a first impression of him as “observant dilettante” is a false impression. He’s not some hanger-on, a mere “scavenger of anecdote.” One recurring motif in Out There: Mavericks of Black Literature, Busted in New York and Other Essays and Come Back in September is the narrator as “recessive presence in his narrative.” The challenge Come Back in September seems to set itself, one Hardwick gives careful thought in “Memoirs, Conversations and Diaries,” an essay published the year Pinckney was born, is what shall the narrator “do with himself in the reminiscence? Shall he admit his own existence, or is that an unpardonable self-assertion?” In his introduction to The Collected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick, Pinckney talks about “the advance and retreat of the narrative self.” The Goncourt Journals document the literary and artistic milieu of Baudelaire, Degas, Flaubert, Mallarmé, Rodin and many others. As meticulously as the Goncourt brothers documented Paris between 1851-1896, Pinckney attempts to document the literary and cultural history of Manhattan c. 1973-1989.

The final year of the Vietnam War draft preceded Pinckney’s transfer to Columbia from Indiana University. Thick spectacles earned him an A4 exemption. Pinckney didn’t dodge the draft; but he might have dodged a bullet. Back in Bloomington, he’d thumbed his first issue of the Review; had no idea what it was. The red couch supports vast reading. A bound volume, likewise red, contains every issue from the Review’s first 10 years. A slow reader, Pinckney pores over each and every issue, cover to cover, piece by piece. Here was Baldwin’s open letter to Angela Davis. As Pinckney absorbs oral and literary history, he’s also keeping a diary. He crams into these scenes, table talk and character sketches as many recommended readings as he can recall. Sontag suggests a dozen different opera recordings. Hardwick piles on back issues of The New Yorker. Pinckney’s lists can never be exhausted in a single lifetime. That’s the whole point.

“Writing,” Hardwick warns, “will not make you happy.”

She prepares Sunday dinner.

Pinckney clears the plates.

2. The Groups

An individual alone in a room fills that room with conflict. Opinionated individuals entering and exiting through the condo elevator make that room combustible.

Distinct groups overlap in Come Back in September: the haut monde of Upper West Side intellectuals and artists, Pinckney’s predecessors; and Pinckney’s contemporaries, the demi-monde who became the 1970s New Wave scene of Lower East Side/East Village literary, performing and visual artists.

Pinckney more than once mentions Colette. He is, like her, a keen observer of women’s relationships—their rivalries, loyalties, betrayals and seduction—when alpha males like Lowell and Wilson are not around. Pinckney’s presence is either tolerated by the lion pride or, in the case of his future editor Barbara Epstein, simply ignored.

“I was not a peer.”

Many gatherers convened on the red couch have been portrayed in biographies, critical studies and memoirs, most recently by anthologist, critic and short-story writer Robert Boyers in Maestros & Monsters: Days and Nights with Susan Sontag and George Steiner.[1]

In the Bildungsroman or coming-of-age novel, a character “like Werther, [is] a youth forever seeking his conversion experience.” In the Künstlerroman, the narrator portrays an artist’s growth to maturity. Come Back in September recalls both The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge and Conversations with Goethe. Pinckney mentions Red and Black, a kind of bildungsroman. But Stendhal’s work is that of a mature writer nearing his end. Come Back in September is that of a young writer approaching manhood. When Pinckney mentions The Education of Henry Adams or Hardwick’s essay about McCarthy’s Memories of a Catholic Girlhood or Intellectual Memoirs: New York, 1936-1938, you feel Pinckney’s setting forth criteria by which he wants his past and future books judged.

***

By the time Pinckney attended her creative writing class, she was in her late 50s, and every inch Elizabeth Hardwick. She had “redefined, reasserted herself as a writer.” She’d become Mrs. Elizabeth Lowell before Pinckney was born. “He was more experienced at having wives than I was at being one.” She and Robert Lowell separated after two decades, then divorced before Pinckney enrolled in her class. Professor Hardwick has not yet, for Pinckney, become “Lizzie.”

Hardwick did take Pinckney under her wing. But there the Colette comparison ends. Pinckney never portrays Hardwick as a maternal surrogate. A representative of “the first black suburban generation,” Pinckney comes from a solidly middle class family—2.5 children, a sheepdog and a mean-eyed cat named Ming. At Spellman, his mother majored in mathematics. She likes to gamble. A Morehouse man, his dentist father is the only member of the household who doesn’t smoke. Dander’s imbedded so thick into the green pile carpet that asthmatic Dr. Pinckney wears surgical masks even at home.

***

Women on the red couch aren’t “above envy.” They fuss and fight about whether or how to support Feminism. Audrey Anne Rich (as Hardwick calls the absent one) attacks Seduction and Betrayal: Women and Literature. Susie rushes to Hardwick’s defense. “Susan cared very much for Elizabeth’s work.” Pinckney says. “And she wanted Elizabeth to care for [Susan’s], of course, with a needy, insecure, throbbing hope.” Susan phones Lizzie, who doesn’t always return her calls. At first, Epstein resists the idea of even publishing Sontag’s work in the Review. (Sontag’s rough drafts are an editorial nightmare.) Even supporters, to say nothing of her enemies, criticize Sontag as a tin-eared interloper among short-story writers and novelists. Her prose just lumbers along, like her large frame.

Sontag calls Pinckney up on the phone—a first! She hashes out ideas for a novel that will become The Volcano Lover. Pinckney says that between her first novel The Benefactor and her short story “The Dummy,” from I, etcetera, Sontag “identified what she could not do as a fiction writer.” Some might doubt her prose artistry. Others criticize her for failing to take herself, Hardwick says, “with that grain of salt which alone makes clever people bearable.” Whatever your take on Sontag, there’s no denying how hard worked.

Lizzie liked Sue; wrote the introduction to A Susan Sontag Reader. But Barbara, who sometimes feels dropped by Susan the way Susan feels dropped by Lizzie, liked Mary better, despite McCarthy’s occasional high-handedness. Sue could be cold and distant, toward even old friends—especially if she thought she wasn’t earning the kind of money celebrity entitled her to.

Hardwick invites Sontag to summer at her home in Maine.

Sontag begs off.

Hardwick, a chronic insomniac, writes back to say she’s tired anyway. Maybe it’s better if Sontag doesn’t come, after all.

Sontag changes her mind.

“Don’t be silly.”

Sontag’s coming anyway.

Typical!

Don’t even get them started on the subject of Lilly Anne Hellraiser.

***

Pinckney says publishing a book or even submitting a Review essay to Epstein caused Hardwick anxiety. She dreads disapproval. Epstein knows this, but takes her sweet time getting back to Hardwick on the status of a given piece. Hardwick hands in her draft. With no immediate writing project to funnel all that nervous energy into, she frets. Clears her desk. Does household chores like emptying the trash. Straightens out the bed sheets. Takes a trip to the hair salon, which keeps Hardwick looking exactly as she always does in her dust jacket photos.

But Hardwick and Epstein, friends and collaborators at the Review, are also neighbors. They live in the same building, a few doors down from each other, between Columbus Avenue and Central Park West. They might chat on the telephone, on any given day, several times a day, about this or that. Hardwick’s just dying to replace the kitchen wallpaper.

As a critic with a half-century of experience meting out punishment, Pinckney surely anticipated what reviewers would say about Come Back in September. Then again, people say mean things about The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Not an easy thing to balance what Boyers calls “inspired anecdotage” against what Pinckney disparages as “higher tittle-tattle masking as cultural history.” The “plenitude of names” in Come Back in September may seem excessive. The exact opposite is true. New York being New York, everybody you knew knew a Somebody. You were likely to see anybody, anywhere, at any given time of the day or night. In all fairness, Pinckney’s withholding as many names as he could have dropped. Knows damn well Hardwick would be the first to eviscerate “a book full of silly remarks.” If malicious gossip or witty banter were the entire point of Come Back in September, it wouldn’t be nearly as useful as it is.

Don’t misunderstand. Comes to literary politics, Darryl dish dirt with the best. As dramatist and novelist, he knows how to set a stage or light a scene. Some of what Pinckney does is just solid character-building. One character describes another, allowing the reader to form an independent opinion about conflicts Pinckney himself may or may not be partial to. Pinckney and Epstein begin socializing in settings beyond the red couch. During that first luncheon between just the two of them, Pinckney is nervous. Each “knew too much about [the] other, and yet [we] were not [intimately acquainted] ourselves.” Will Pinckney bore Epstein to tears? How much gossip about Lizzie dare he reveal to Barb?

Yeah, sure: there are dinner parties hosted by or for the rich and famous. Some events Professor Hardwick deigns to attend; others she don’t. “[D]rink heightened” Lowell says, the “flow of elocution.” The quantities of alcohol pouring out this memoir are sobering: pre-cocktail-party cocktails; cocktail-party cocktails; and after-party cocktails. Vodka is the juice of choice—gimlets, by the pitcher—sometimes bourbon, couple Heinekens or, if Hardwick has a bottle hoarded away in the fridge, grappa. Too much to drink can make her hard to handle. Filters fade. After “any number of martinis,” she might chew you out. Or get weepy, lisp to Cal that she wants to go home, to mamma. Once, Pinckney brings to class at Barnard a Styrofoam cup full of a suspicious, clear liquid. Turns out to be just what the doctor ordered. Professor Hangover knocks back a swig.

A child of Depression-era Kentucky, the eighth of eleven children, Hardwick had no use for Jazz Age excess. Her group was remarkable for its longevity and productivity in spite of how much they drank. John Berryman’s or Delmore Schwartz’ “steep, drunken decline” seem the exception that proves the rule. Pinckney’s prehab episodes “acted as a brake,” he says, “on [one’s] self-destructiveness.”

***

“In the Wasteland,” Hardwick’s essay about Joan Didion, is an indicator of the overlap between Pinckney’s established predecessors and emerging contemporaries. Howard Brookner and Jim Jarmusch are trying out different guises for their “apprentice selves,” performing “identity experiments” — up to and including, in the case of dysphoric Lucy Earle Sante, gender reassignment.

“I am not a teacher,” Hardwick complains as student papers pile up, ungraded, in obtuse accumulations. Child-rearing, tuition-payments at Upper East Side schools like Spence or Dalton, panel discussions, speeches, lectures—these were among the obligations Hardwick longed to be unburdened of. “I am a writer.”

Down the Lower East Side, at CBGB, the B-52s don’t even go onstage till midnight. Club-kids stay out all night, smoke Thai stick, applaud drag balls at the piers, huff nitrous oxide or tab microdot, argue about Patti Smith’s Vietnam Victory Day concert in Central Park, do cocaine in pancake-mix quantities in order to stay awake, and quaaludes to take the edge off the cocaine. They crash couches, kitchen bathtubs or mattresses spread over undulating floors in tenement walk-ups, and sleep well past noon. When they stop partying long enough to eat a little something, there’s The Kieve, a Ukrainian diner on Second Avenue at Ninth Street. Somehow, they survive six parties a week—three on Saturday, three more on Sunday. How they get home most dawns nobody remembers.

***

As student-writer, Pinckney is doubly “vulnerable to the power of nickels and dimes.” Hardwick wasn’t, he admits, a good cook. To her, it seems like just another chore. But she hates to waste food. Hardwick burns the butter. They eat those bay scallops anyway.

Pinckney scrounges loose change, here and there. Blows on “smoking Black Russians and drinking Black Russians” what little pocket money he makes temping at Harcourt Brace. Ditches that second-hand-bookstore job; goes to work part-time for Professor Hardwick.

This financial arrangement is murky. Hardwick hired and retained two different cleaning ladies (one for the summer home) at the very generous sum of what is still, half a century later, the prevailing minimum wage in DC—$7.50 an hour—for a minimum of two hours. Presumably she paid Pinckney as much if not more to reorganize the bookshelves, assemble furniture, drive her up Connecticut to that teaching gig, tend bar. But the emotional and intellectual fringe benefits of such a relationship, to a former student—gay, gifted and black—and to a doyenne of literary New York, seem clear if hard to quantify.

Lowell, she said, used up all the oxygen in the room. Without him, she breathed easier. Whereas Stanley Crouch theorized the presence of a mad, black queen posed no threat to the ex-husbands or secret lovers of Hardwick’s inner circle. Having a confidante around the house, one she didn’t have the chore of performing sex-acts with, enabled Ms. Lizzie to live her life as a writer and single-mother in New York City, out in the open, unburdened by what she called “coupledom.” Hardwick critiques Pinckney’s poems, short stories and essays. Slips him a $20 bill for cab fare, subways in New York City being then as now dangerous at certain hours. Her nights were free to do with as she pleased: read Anna Karenina, one chapter at a time; drink; gossip with others of her group on the phone.

In the long run, books seem to bond them more than things that irritated each about the other might cause them to fall out.

“You’re not,” he insists, “listening!”

(Hardwick lost her hearing aid.)

“You’re not,” Hardwick screams, “making any sense!”

Hardwick prepares Sunday dinner.

Pinckney loads the dishwasher.

3. The Dolphin

Another bond Hardwick and Pinckney share is poetry. A great deal of verse, much of it unattributed, characterizes Come Back in September, sometimes as a song lyric or a poetry fragment meant to express a mood. After Lowell dies, Hardwick senses his reputation is deteriorating. Just as Pinckney is writing this memoir, FSG publishes The Dolphin Letters, 1970-1979: Elizabeth Hardwick, Robert Lowell, and Their Circle, together with a reissue of Lowell’s sonnet-cycle The Dolphin. Pinckney describes The Dolphin as a story Lowell tells through his poetry of “the end of their marriage and his move to another country in order to be with another woman,” Lady Caroline Blackwood.

Another bond Hardwick and Pinckney share is poetry. A great deal of verse, much of it unattributed, characterizes Come Back in September, sometimes as a song lyric or a poetry fragment meant to express a mood. After Lowell dies, Hardwick senses his reputation is deteriorating. Just as Pinckney is writing this memoir, FSG publishes The Dolphin Letters, 1970-1979: Elizabeth Hardwick, Robert Lowell, and Their Circle, together with a reissue of Lowell’s sonnet-cycle The Dolphin. Pinckney describes The Dolphin as a story Lowell tells through his poetry of “the end of their marriage and his move to another country in order to be with another woman,” Lady Caroline Blackwood.

“we cannot live in one house,

or under a common name.”

Opinion divides sharply about this work. Bishop was Lowell’s close friend, but disapproved of his misappropriation of Hardwick’s letters:

the fiction I colored with first-hand evidence,

letters and talk I marketed as fiction

In a published review, Adrienne Rich called Lowell’s pilferage of Lizzie’s letters “one of the most vindictive and mean-spirited acts in the history of poetry.” Others you might expect to be up in arms say Lizzie “got what she deserved.” The Dolphin rewards close scrutiny as more than a mere confessional melodrama of “stiletto heel/dancing bullet wounds in the parquet.”

Lowell writes that “nothing living wholly disappoints God.” He wrote poems, day by day, from Lord Weary’s Castle till the last of the Selected Poems, as if Poetry still mattered. Keen observation abounds, interior and exterior. “The frowning morning glares by afternoon.” London is instantly recognizable: “Cold the green shadows, iron the seldom sun.”

Hardwick feigns nonchalance. Jean Stafford, Caroline Blackwood — “Robert Lowell,” she said, “never married a bad writer.” But those letters she wrote to Lowell, Pinckney says, “sadly contradict her version of herself” as stoically resigned to their split.

Pinckney unloads the dishwasher.

4. Art of the Essay

The essay of novelistic effect, “neither life exactly,” Hardwick says, “nor fiction,” was “a constant in Hardwick’s writing life,” Pinckney says. It was as high an art form as the short story or novella.

In the mid-1940s Partisan Review, a beacon of what Pinckney calls “that postwar culture thick with earnest literary quarterlies,” published some of Hardwick’s earliest essays. From her very first Review piece, “Grub Street: New York,” until the year before she died Hardwick published essay after essay. In due course, her writings on Virginia Woolf and many others were collected: A View of My Own; Seduction and Betrayal: Women and Literature (with an introduction by Joan Didion); Bartleby in Manhattan; and Sight-Readings. Thirty-five previously unpublished pieces are gathered in The Uncollected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick. All told, we have 1,000 or more pages of her literary journalism.

It isn’t uniformly excellent. Can her harsh words blister paint off literary façades? Yes. Carlos Baker’s biography of Hemingway is the exception that proves the rule. But negative reviews are rare in The Collected Essays. As for Hardwick’s public oppositions, some may seem conservative, even reactionary, depending on your politics. Miz Lizzie knows and loves any number of individual gay men and lesbians, but sees nothing radical about same-sex marriage. Disapproves, in fact, on the grounds that “imitating straight behavior gave it too much credence.” Hardwick’s prose style isn’t overrated, just overemphasized. Because what Pinckney calls her “diagnostic prowess” is what makes Hardwick’s essays formidable.

Pinckney says “there was no other writer like her.” As close a reader as they come, Hardwick was unimpressed by the New Criticism “and its concentration on the text at the expense of the social or historical context,” Pinckney says, “as if language itself could be anything other than social or historical context.” The same went for Structuralism, Post-Structuralism and Deconstruction. Hardwick admired writers of what she considered individual genius like Roland Barthes, but not their imitators. Did Hardwick have a methodology? If by methodology we mean reviewing “what comes before [you] without a fixed theory of value or a hierarchy,” as Boyers puts it, then that was her method: “making a point, making a difference.”

5. The Paper

In Art of the Personal Essay, Phillip Lopate argues that the form dates back to the Romans and to Asia. The English-language essay as we know it presumably begins with Bacon, but flourishes with the rise of journalism in the 18th century and 19th centuries. Today The London Review of Books, launched by The New York Review of Books—Hardwick thought it a terrible idea—has featured literally tens of thousands of contributors. The New York Review, which Robert Silvers liked to call The Paper, was a global “theater,” Pinckney says, of “intellectual history.”

In Art of the Personal Essay, Phillip Lopate argues that the form dates back to the Romans and to Asia. The English-language essay as we know it presumably begins with Bacon, but flourishes with the rise of journalism in the 18th century and 19th centuries. Today The London Review of Books, launched by The New York Review of Books—Hardwick thought it a terrible idea—has featured literally tens of thousands of contributors. The New York Review, which Robert Silvers liked to call The Paper, was a global “theater,” Pinckney says, of “intellectual history.”

The Review embraced intellectual rigor of the kind associated with core curriculum schools like the University of Chicago, where Sontag earned her undergraduate degree. But the Review was never intended as an academic publication. One of the things Hardwick liked best about writing Review essays was she didn’t have to explain the obvious.

Readers of Balzac’s Lost Illusions will get the picture. The Review’s pages were a who’s who of established writers. Stephen Spender stops by the office one day, Bruce Chatwin the next. The Review was also an incubator of emerging talent. Prudence Crowther typesets in the production room. Pinckney and Sante platoon the mailroom, which Pinckney says was “out of control.” Sometimes, Pinckney covers reception.

Silvers, the Big Idea guy, thinks specialization is for other people. Barbara Epstein, the “editor with a poet’s sensibility,” had shaped Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl. Her house style sets the tone for this establishment. Nothing could be printed unless both agreed to it.

“They were like a married couple,” Hardwick says, “only worse.”

“Don’t talk to me,” Epstein stands up for herself, “like that.”

“I will talk to you like that.”

Silvers, seated at a desk as large as his overreactions, has three assistants he can bark dictation and verbal abuse at.

“Where’re those galleys I asked for?!”

The galleys were on his desk.

“What does he mean, he won’t write about Kissinger? Get me Balliol on the phone!”

Barbara’s office is smaller. She has only one assistant. Sometimes Pinckney fills in. After a call with Lizzie, Barbara might instruct Pinckney she is not to be disturbed. He is to take messages.

“Barbara was complicated, but she cohered into a magnificence of concentration as audience, reader, she who left so little trace of her importance to American letters.”

Ruby’s Rectangle[2] is a schematic describing symbiosis in the literary ecosystem. Inside this rectangle, critics occupy the upper lefthand corner, venues occupy the upper righthand corner, publishers occupy the lower lefthand corner, with readers occupying the lower righthand corner. “There is a degree of overlap,” Ruby says, “between the personnel of each of the points of the rectangle: editors sometimes produce criticism; critics form a part of the audience for criticism.” There are critic-practitioners like Updike: novelists, poets or playwrights who review occasionally in conjunction with their work in other genres. “Public intellectuals” or scholar-critics are another type of practitioner. There are staff writers or freelancers, who may or may not be tenured professors or graduate students, contributing to quarterlies, monthlies, weeklies or daily publications intended for a non-academic audience. From the time Virginia Woolf reviewed for the Times Literary Supplement until Pinckney left New York for Berlin, it used to work like this: “publishing houses send advance review copies or galleys to critics who pitch articles to editors who publish them in their venues which are read by audiences.” The game remained the same. Only the players differed.

Then Internet Service Providers emerged in Australia and the US. The agora went virtual, “levelling out certain geographical disparities in industries which are still largely centered out of New York and London, diminishing the value of in-person networking, and opening the available talent pool to critics based elsewhere.” Personal computers and email have fundamentally changed the way pieces and books get published—not always for the better. Out there in the virtual slush piles, an ever-increasing amount of printed matter and online content leaves ever-diminishing amounts of time and space in which to achieve what R.P. Blackmur calls “internal intimacy” with it, one text at a time. As for the canon—Matthew Arnold’s “best which has been thought and said”—the canon is a Montgomery firehose all the critics from all the literature-producing countries put together can’t possibly drink from. For now, reviewers like Pinckney remain relevant. The Review, that first draft of 20th century cultural, literary and intellectual history gets put to bed, over the course of a 50-year argument, one essay at a time, issue after issue.

***

Pinckney babysits the Epsteins’ young children. Is entrusted with the keys to 33 West 67th Street. At Castine, an hour’s flight to and another hour’s drive from Bangor, Hardwick lives from Memorial to Labor Day at her summer home in Maine, reading, writing, relaxing with Mary McCarthy.

Pinckney fetches the mail.

6. The Making of a Critic

What would or wouldn’t run in the Review was strictly confidential. Epstein leaks the court’s deliberations. Pinckney gets the nod. His first Review essay, on the class system in black America, appears 4 August 1977. Come Back in September describes Pinckney’s maturation from protégé to literary critic and regular contributor “to one of the leading intellectual journals in English.”

In back issues of the Review, Pinckney discovered some of the great postwar essayists anthologized in John Gross’ The Oxford Book of Essays. As a young critic, Pinckney starts out publishing unsigned reviews in Kirkus. Even then, he showed a knack for taking on important titles like Robert Hemenway’s biography of Zora Neale Hurston. But Kirkus reviews are short-form notices of 250 words or so. Your hands are cuffed. Ruby explains the formula: “a little background on the author, followed by a synopsis of the content of the book under review, a comparison to existing titles, and finally a cursory one or two sentence whose purpose is to recommend or dis-recommend the book to potential buyers.” It’s essentially a Consumer Reports rating system.

The New York Times Book Review or Wall Street Journal typically publish more or less straight reviews running 750 to 1500 words. “Writers of imaginative, longer-form review-essays,” Ruby says, “take more time and space—2,500 words and sometimes [up] to 10,000 words—to make aesthetic judgments and provide literary/historical context, space enough to allow for more sophisticated interpretations and formal play. These reviewers are sometimes as well-regarded, if not more so, than the artists they are reviewing.”

Pinckney borrows books from Hardwick’s vast library, like V.S. Pritchett’s The Living Novel. “I liked his idea that nineteenth-century Russian literature was about the isolated, lonely man or woman in his room.” Pinckney continues, “I was on the right track. It was the kind of book that added to my list of names to reckon with.” Pinckney reads Dead Souls, will later journey to St. Petersburg, write about Pushkin. Pinckney comes to the conclusion, and Hardwick agrees, that great Russian writers are antecedent to Wright and Ellison in a way great 19th century Americans novelist are not. One might add that Dorothy West’s “Elephant’s Dance: A Memoir of Wallace Thurman” —the muscular kind of writing Hardwick admires in other women—reminds you of Gorky’s Reminiscences of Tolstoy, Chekhov & Andreyev.

Literary, performing or visual artists can never really speak for; they can only speak as. To Pinckney’s credit, Come Back in September limits itself to one African-American’s life story. It never strains after a unified theory of black identity. Pinckney’s body of work isn’t binary, politically engaged or disengaged. He does acknowledge the psychological “conflict between national history and racial identity.” He also self-identifies as a black man of “the gay subculture,” experiencing the avant-garde at a time when he was discovering the sexual freedom brought about by gay liberation post Stonewall. Pinckney’s reading is wide, his polemics varied. It isn’t possible or even necessary to agree with him all the time, especially on subjects you yourself have thought long and hard about. Pinckney tight-ropes between cosmopolitan aesthete and public intellectual. Sometimes—he teeters—and you glance away, afraid to watch him fall.

Busted in New York makes clear the extent to which Pinckney’s leveraging his Review platform. As Obama administration 1 blurred into administration # 2, Pinckney weighs in on the rise of “anti-immigration populism” and many other controversies. Pinckney and the Review continue relevant even in an era of burgeoning hybrid online/print outlets. But opportunity, what Pinckney calls “[t]he reinvigoration of the marketplace of discussion about race” at CNN, Fox News, MSNBC and PBS came at a cost. Busted—more so than other works under discussion here—strains under the burden of mere reaction to a 24-hour news cycle. A given periodical’s frequency of publication isn’t really at issue here. The New Yorker is a weekly. Poetry editor Howard Moss (Moss don’t do dirty dishes; he just throws ‘em out) published Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art” in The New Yorker. That villanelle took Bishop six months to write. Still, one concedes Boyers’ point: [i]t “is notoriously difficult,” he says in his introduction to George Steiner at the New Yorker, to make imaginative literature of lasting quality, critical or otherwise, under tight deadlines and skimpy word-counts “written for a weekly or monthly magazine.”

Hardwick paid him a compliment by saying Pinckney’s essays sound nothing like hers. True. He was finding his own voice. “You’re not,” says the Old Campaigner, “as radical as I am.” Also true. Hardwick is the more daring essayist of the two.

Pinckney tidies up, purges old files, rearranges bookshelves.

7. Grub Street: Berlin

The winter Baldwin died, Pinckney attended the St. John the Divine memorial service. Hardwick, eyes bloodshot from crying, squeezes his hand. In his mid-20s, Baldwin had used his $1,500 Rosenwald fellowship to escape New York for Paris. Pinckney says Baldwin paid “for the airline ticket and stayed broke for the next nine years.” Did Pinckney in his mid-30s use a Whiting Award to move to Berlin?

The winter Baldwin died, Pinckney attended the St. John the Divine memorial service. Hardwick, eyes bloodshot from crying, squeezes his hand. In his mid-20s, Baldwin had used his $1,500 Rosenwald fellowship to escape New York for Paris. Pinckney says Baldwin paid “for the airline ticket and stayed broke for the next nine years.” Did Pinckney in his mid-30s use a Whiting Award to move to Berlin?

Before 1989, the Berlin Wall stood at the heart of the once and future German capital, still then a backwater. Pinckney squats in a Turkish neighborhood, eating Turkish food, sleeping in his clothes. When he speaks of “the expatriate’s improvised, precarious, lonely existence” he’s speaking from experience. Sometimes antecedents of “the history of the black American expatriate writer in Europe” are known quantities. Not long after World War II, first Wright then Baldwin went into exile. Ralph Ellison and Chester Himes followed, “writing in the same Europe” but had very different experience of exile. Ellison returned “home.” Wright stayed on in Paris. Other antecedents remain less well known. Out There: Mavericks of Black Literature is Pinckney’s reading of three expatriates: J.A. Rogers; Vincent O. Carter; and Caryl Phillips. Pinckney’s critique of Carter’s The Bern Book consciously recalls Baldwin’s essay “Stranger in the Village.”

By now, Baldwin’s differences with Wright are common knowledge. “Wright went to Europe to unmake himself as an activist,” Pinckney says, while “Baldwin had to go to Europe to become one.” Readers may miss the connection between Wright’s Eight Men, its “use of white characters” to explore “some of the themes that gripped him as a black man” and Giovanni’s Room, about which Pinckney says suggestive things. On the centrality of Henry James (“a non-practicing queer”) Hardwick and Pinckney agree. “Giovanni’s Room was the one Baldwin novel that to me showed most directly James’s influence on him, because it followed the seasons, like The Ambassadors, and David’s being American was as much an impediment to him as it was to Lambert.”

The kind of long-form essays Sontag compiled in Against Interpretation can take six months to craft. It can take years or even decades to compile a curated collection of such essays in book form. Pinckney works on pieces for what seems like forever. Silvers or Epstein might insist on further revisions. The money’s running out. Pinckney no longer composes on a typewriter, but his computer is on the blink. Badly needed payment is withheld until satisfactory edits are approved. Living “without proper papers or regular employment,” he’s reduced to munching bagged carrots and apples. Pinckney soon realizes that “scrounging around was the opposite of liberating.”

Pinckney does rehab; finally finishes that first novel, High Cotton.

8. Art of the Diary

Readers approaching Come Back in September, even those who know Pinckney as a playwright, novelist and critic, may be unaware he started out, like Baldwin, writing poems and short stories. Early consumer reports complained that Come Back in September seemed fragmentary, careless. Out There makes clear Pinckney is grandmaster of a formally elevated style which, though “high-minded and arch,” is also laudable for its absence of the overheated rhetoric he calls “the fabric of false eloquence in American Prose.” If Out There is its polar opposite, if Busted in New York is the middle ground, then Come Back in September is an outlier experiment Pinckney seems willing to push to its limits.

Which does give Come Back in September a jaggedness very different from the luxury-vehicle-smooth ride of Out There. Expurgated diary entries and personal correspondence from Part 8 confirm that Parts 1 through 7 are much less fragmentary than they seem. Pinckney’s rapid shifts in point of view (like Stendhal’s), his sly allusions, his convincing portrayal of characters’ complex motivations and inner lives, his precise evocations of physical environments by means of sensory detail, his black comedy—all these attest to a formal design.

Pinckney’s reviewed enough bad books to know. Certain elements of creative nonfiction must be troweled sparingly—description, for instance. For this reason, the dramatic cityscapes we do encounter stand out. “Shadows vanished from the hot September pavement. First a few drops. They hit me as I walked next door. It was going to be a relief from the humidity. As soon as I stepped from the bookshop, the sky broke … wind swept the rain down West Ninety-fifth Street in Boxer Rebellion waves, hundreds of thousands of drops attacking my shoes. I [made] a run for the subway.”

E.M. Forster might agree: as characters go, the one irradiating the whole of Come Back in September, the one lingering in the mind as or more insistently than Bishop, Lowell, McCarthy, Rich, Sontag, Wilson or so many others do is New York itself. So much of the city one knew between 1964 and 2014, so many things one took for granted over the course of 20 years living there, over the course of 20 years’ absence—so many entries in “the great table of contents that was Manhattan” are vanished—gone: cast iron radiators in Pinckney’s apartments clang like poltergeists, hiss or rattle, even when they give off no usable heat; the “odors of incarceration”; typewriter repair shops; that black-beans-and-yellow-rice Cuban-Chinese joint on Broadway, La Caridad; the holy hush, at the other end of the culinary spectrum, of luncheon at Lutêce, where on any given weekday no more than a dozen of the world’s powerful women and men whispered among themselves, and you were not to gawk when the Chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank was seated one table over from the conductor of the Metropolitan Opera.

“February was so cold I thought my face would break.”

Here was New York.

Come Back in September conjures it back to life.

***

“I sometimes wonder what a later time will call this era.” Whatchamacallit came to an end. Hardwick, who didn’t always trust editors, did trust Epstein. Notices the Review wearing Epstein down. Hardwick’s last piece appeared in the Review the year before Epstein died. Elizabeth Hardwick died aged 91.

Cal and Lizzie were gone. For Pinckney and his contemporaries there was morning in their hearts. Some got discovered, became practitioners in their own right. Doors opened. Sante publishes her first Review essay, on Elvis Presley, and goes on to publish Low Life. Howard Brookner directs a documentary, Burroughs: the Movie. Jim Jarmusch directs Stranger than Paradise, Down by Law, Mystery Train, Night on Earth and Slingblade. A fixture at the Review for almost half a century now, Pinckney has become what Hardwick once was: Establishment.

Table of Contents

Kevin Anthony Brown is author of the forthcoming essay collection Countée Cullen’s Harlem Renaissance: A Personal History (Parlor Press, expected fall 2023) and translated Ocosingo War Diary: Voices from Chiapas, by Efraín Bartolomé (Calypso Editions). At the City University of New York, Kevin double-majored in Spanish and literary translation & technical interpreting (T&I), studying with Gregory Rabassa and other faculty from Spain and Latin America. His articles, essays, interviews and reviews on the art of translation have appeared in Asymptote, The Brooklyn Rail, The Delaware Review of Latin American Studies, eXchanges, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Mayday, Metamorphoses, Rain Taxi, The Threepenny Review and Two Lines, among others.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast