by Geoffrey Clarfield (April 2023)

By the Water, Jane Peterson, 1930

A Brief Introduction

I was admiring the enormous thorn tree spread out in front of me, when a man stopped me and asked, “What kind of tree is that?” I am the most amateur of naturalists but surprised myself and answered, “It’s an East African thorn tree. I don’t know the species name. But there is one just like it in Nairobi, Kenya at the Thorn Tree Café. It was planted there during colonial times when Hemingway visited Africa. It remains in place to this day.”

I looked at the man a little more carefully. He was in his seventies, in good shape. He had a northeastern American accent, perhaps from New England. He wore a straw hat with a black band, a blue shirt and khaki brown pants. He had a white beard and bluish eyes. Then it hit me, I asked him, “Have you ever competed in the Hemingway look alike contest held each year in Florida?”

“No” he said. “But I have been told by someone who knew Hemingway well that, had he allowed himself to live, I would be his spitting image at this age.” I answered, “I believe that.”

The man in question spends six months in Rhode Island and six months in sunny Sarasota. He is not the first nor will he be the last northeastern to relocate here. He volunteers part time as a guide at the Ringling Museum and tropical gardens. He is a book seller, a man who likes to read and talk.

Thinking of Florida during Hemingway’s day and today (March 2023) I marveled at how much has changed here and how little of Hemingway’s Florida remains. I asked myself, “What would be the story of today’s Florida?

Certainly not that of bohemian Northerners in search of big game fishing and hunting in the Everglades, although that can still be done.” There must be something else. And I am afraid I have the answer. Everyone and their mother’s son want a piece of Florida. So do I.

But I was not the first.

The People Who Came Before Him

Let us start at the beginning, at least at the human beginnings of Florida as people were here thousands of years before Hemingway’s ancestors crossed the Atlantic, centuries ago.

Let us start at the beginning, at least at the human beginnings of Florida as people were here thousands of years before Hemingway’s ancestors crossed the Atlantic, centuries ago.

America’s first peoples, the peoples that Columbus mistakenly named Indians because he thought that in coming to the Caribbean he had arrived in East Asia, arrived in Florida thousands of years ago. They were the myriad descendants of the migrating people who had crossed the Bering Strait when there was a land or ice bridge between Asia and the Americas during the last Ice Age, 12000 or more years ago.

Some prehistorians believe that they hunted their way across the continent and ended up in Florida after having killed off the “megafauna,” those marvelous dinosaur-like beasts, like the giant sloth, the ancient horse and camel and other huge animals whose renditions by modern painters grace the halls of so many of America’s Natural History Museums.

Even so, today’s archaeologists and the priests of the Conquistadores many of whom kept good records about the Indians that they encountered, described them as tall, robust, well fed and healthy.

Today’s archaeologists tell us that tribes such as the Calusa who lived south of Tampa and across the shores and estuaries of southwest Florida were a typical bunch, leaving behind massive shell middens, evidence of their ability to live off the land, something the later incoming Spaniards never managed to get right. Perhaps their religious hostility towards the “natives” prevented them from seeing what was in front of their eyes, strong and well-fed people who in some cases did not need to farm.

Much of the physical remains of these people have disappeared under the golf courses and condos that now dot the coast at either end of the ten thousand islands, part of which thankfully are now a national preserve (although a few hold outs have kept homes on the islands, previous property rights behind still being strong in the land of the free). And so, I took an afternoon boat tour among the islands.

The water constantly changes colour, from blue to green to purple. The birds are abundant, and I saw eagles, ospreys, pelicans and ibis. Dolphins frolicked in front of our boat and although the area is relatively well protected there were many other boaters and fisherfolk on the face of the waters. Still, when passing a mangrove studded island with a small sand bar, one can imagine the tall robust Calusa poking about in the shallows and harvesting the clams and mussels that gave so much depth to their “paleo diet” of water-based protein and gathered fruits.

We get a glimpse of the creativity of these peoples in a rare exhibit of tribal masks that are stored at the University of Pennsylvania’s ethnographic museum. Apparently, the Calusa people carved and painted elaborate masks that one assumes were used during ritual dances. They were saved from the mud which had miraculously preserved them by Frank Hamilton Cushing, a 19th American ethnographer who had done participant observation and ethnographic studies of the Zuni Indians of the southwest, long before an immigrant German ethnographer “reinvented” and labelled participant observation as the bedrock method of modern anthropology.

Masks

Anthropologists are not supposed to do this but when I look at just four of these marvelous masks I recognize the origins of visual and plastic art in them, as well as my guess that these masks were danced and represented departed human spirits, animal spirits and had something to do with Shamanism and the myths of creation of the people in question, ritual practices that made the otherwise ecological and practical remains discovered and inventoried by archaeologists filled with the numinous, making every place or special places within these people’s territory sacred, and which perhaps during these rituals brought them back to the time of creation.

Anthropologists are not supposed to do this but when I look at just four of these marvelous masks I recognize the origins of visual and plastic art in them, as well as my guess that these masks were danced and represented departed human spirits, animal spirits and had something to do with Shamanism and the myths of creation of the people in question, ritual practices that made the otherwise ecological and practical remains discovered and inventoried by archaeologists filled with the numinous, making every place or special places within these people’s territory sacred, and which perhaps during these rituals brought them back to the time of creation.

Perhaps like the Yanomamo, one of Amazon South America’s most researched and previously uncontacted tribe, they believed the following:

The Yanomamo conceive of the cosmos as comprising at least four parallel layers, each lying horizontally and separated by a vague but relatively small space. The layers are like inverted dinner platters; gently curved, round thin, rigid and having a top and a bottom surface…A good deal of magical stuff happens, a kind of netherland dominated by spirits, a place that is somewhat mysterious and dangerous…

The Calusa may have believed in a similar or even a related cosmos.

Archaeologist William A. Marquardt has written the following about the Calusa after they had encountered the Spanish:

…In post contact times, people continued to be buried individually in sand mounds, sometimes with European goods. These mounds are the contexts most likely to have been disturbed over the past century by explorers and looters, and so the contextual evidence that might help bridge the gap between precontact Safety Harbor-related patterns and those of the post contact period is lacking. Among the sixteenth-century Tocobaga, when a principal chief died, his body was dismembered and boiled until the flesh separated from the bones. In a temple the bones were joined together and following this ritual the people fasted for four days. Finally, “all the Indian town,” “making much reverence,” joined in a procession honoring the bones (Worth 1995: 344). Sixteenth-century records say that when a Tequesta chief died, his larger bones were separated out and kept in a box in the chief’s house, to be venerated by the whole village, whereas the smaller bones and flesh were buried. In the same box were placed bones obtained from the heads of whales captured communally in the winter (Worth 1995: 344-345). The Calusa greatly feared the dead (Hann 1991: 329, 423-424). Further, they believed that a person’s soul could become separated from the living body. When this happened, a shaman was summoned to locate and reinstall it. A fire was built outside the hut to discourage the soul from venturing out again (Hann 1991: 238). Another recorded belief is that each person had three souls: one in his shadow, another in his reflection, and a third in the pupil of the eye. The last of the three lived on after death. Offerings to the departed were placed on mats at grave sites…

And yet, when the Spanish and Calusa interacted over the next two centuries, the Spaniards did not hesitate to kill to kill one of their greatest chiefs in 1556 for refusing to convert to the Catholic faith.

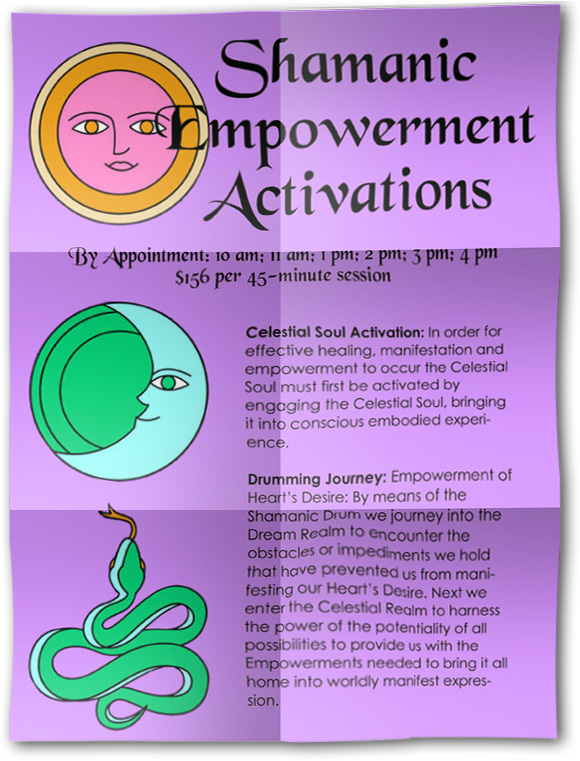

The Spanish, the French, the British and the Americans did everything they could to destroy the Shamanistic religion that held people like the Calusa together, as later newcomer Indian Americans like the Seminole. All of these Europeans tried to convert the natives to Christianity but in the early 21st century Christianity in these regions is fading and Shamanism has returned, although in an updated manner, geared to 21st century needs. Here is just one posting from Florida.

The Spanish, the French, the British and the Americans did everything they could to destroy the Shamanistic religion that held people like the Calusa together, as later newcomer Indian Americans like the Seminole. All of these Europeans tried to convert the natives to Christianity but in the early 21st century Christianity in these regions is fading and Shamanism has returned, although in an updated manner, geared to 21st century needs. Here is just one posting from Florida.

Of Airports and Iguanas

There is an airport in Tampa. There is an airport in Sarasota. There is an airport in Venice, Florida. There is an airport near Fort Meyers. And there is an airport in tiny Naples.

Those who are foolish enough (or who do not mind the constant noise) to rent a holiday property in downtown Naples are serenaded by close encounters with incoming and outgoing jets. The noise usually dies down in the evening and it is not reflected in the beautiful photos that adorn the tourist magazines with their gorgeous depictions of Naples Italianate downtown architecture and spectacular beaches.

These airports have brought a steady stream of immigrants and visitors to Florida during the last seventy years and these humans have often directly or indirectly brought new species of animals to the State, invasive species as they are called by biologists, which if allowed to run riot, would and will destroy the Everglades as we have come to know it.

If there is one book that anyone and everyone who comes to Florida must read, it is Rivers of Grass, by Marjorie Stoneman Douglas. Marjorie was a northerner and had an upscale liberal arts education from Wellesley College in Massachusetts. She had poetic and literary inclinations and, when her father relocated to Miami in the early days of the 20th century, founding the Miami Herald, she came on board as a writer. She looked at all and every aspect of developing Florida and fell in love with the Everglades.

She realized, long before most people, that it was a unique biome, a river of grass, worthy of preservation in the spirit of Teddy Roosevelt who started the first national park of the USA in Yellowstone.

In 1947 she wrote a conservation classic The Everglades: River of Grass that made her nationally famous. It became a best seller and catapulted her to nationwide fame as women writers and the environmental movement were in their early days (decades earlier, women had been at the forefront of the Audubon conservation movement).

Marjorie was divorced and childless, so the Everglades took on the role of her children. She campaigned endlessly for its preservation and conservation, lobbied ceaselessly and succeeded to a great degree. When you visit parks and conservation areas in Florida, you will come across this famous passage from her book:

There are no other Everglades in the world. They are, they have always been, one of the unique regions of the earth; remote, never wholly known. Nothing anywhere else is like them.”

Years later, my late mother bought me the book as a gift. Whenever I think about Douglas I also think about my mom.

Through attention to the scientific literature and her poetic way of describing the Everglades, she nearly single-handedly created the legal framework that preserved this watery wilderness for coming generations. You can go on YouTube and see her interviewed. She is confident, feisty, no nonsense and exudes a good-natured enthusiasm tempered by political know how. She died at the ripe old age of 108. It is now up to the younger generation to deal with the latest threat to the Everglades, which one could sarcastically call, “runaway pets.”

Florida’s semi tropics are ideal places for tropical animals from Africa and Asia. People with exotic tastes for Burmese Pythons or Asian Monitor lizards appeared to have brought in these animals as pets and then let them enter the wilderness.

Today the state of Florida has a growing list of these invasive species and sometimes allows bounty hunters to go out and kill as many of them as possible. National Geographic is chock full of documentaries that track night time hunters of these Burmese pythons, trying to reduce their population as they outcompete the birds and alligators in the swamp. If Hemingway were alive today this would be the kind of news from which he would derive a chilling short story:

Florida Teen Wins $10,000 for Hunting Invasive Pythons

The annual Florida Python Challenge combats the destructive snakes, which have taken over the Everglades.

Participants of the 2022 Florida Python Challenge captured a total of 231 invasive pythons during the ten-day competition.

Nineteen-year-old Matthew Concepcion killed 28 invasive snakes this year during the annual Burmese python hunt in Florida, earning him the $10,000 Ultimate Grand Prize, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission announced.

“Still on cloud nine,” Concepcion tells Jessica Vallejo of NBC 6 South Florida. “Couldn’t believe it.”

The ten-day competition was created in 2013 to help rid the Everglades of the invasive snakes, which have few natural predators and are decimating native species.

Burmese pythons were introduced into the U.S. from Asia as part of the exotic pet trade. Between 1996 and 2006, about 99,000 pythons were brought over. Experts believe that owners released the snakes after they grew too large to handle, and the reptiles began breeding in the wild. In 1992, Hurricane Andrew destroyed a python breeding facility, and subsequent storms have likely continued to let snakes escape their enclosures and get loose in the Everglades.

The pythons have since gobbled up mammals, birds and reptiles, even preying on animals as large as deer and alligators. Between 1997 and 2012, raccoon populations dropped 99.3 percent, opossums plummeted 98.9 percent and bobcats declined 87.5 percent in the southern region of the Everglades. Marsh rabbits, cottontail rabbits and foxes virtually disappeared.

To make matters worse, the voracious snakes breed quickly: Females can lay 50 to 100 eggs at a time, per the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

If you think that it is only pythons and lizards that are invading Florida, think again. Invasive species include feral hogs, cane toads, lion fish, Cuban tree frogs, giant African land snails, green mussels, cats and tegu lizards.

A colleague who lives in Sarasota told me the following:

Iguanas are everywhere. If you are an outdoors person you will eventually run into them. They are mean creatures. They bite and can whip you with their tails, like miniature dinosaurs. They do not do well in the cold. Once or twice a year when Sarasota hits freezing point the lizards go into a deep hibernation, and they look as if they are motionless and frozen. If the cold snap comes when the lizards are still on low hanging branches of trees, after a while, they can fall to the ground. They will look dead, but they’re not. Like vampires, they will rise again when things heat up. People on bicycles have been known to be hit by the occasional falling “frozen iguana.” It seems like science fiction.

If he were alive today Hemingway would no doubt support the bounty hunters of invasive species but only after he had submitted himself to a lecture by Marjorie. The two of them might have bonded, writer to writer. It could be the basis of a fine short story, for Margaret also wrote fiction.

Can We All Live Like Hemingway?

Hemingway once caustically wrote that, “The game of golf would lose a great deal if croquet mallets and billiard cues were allowed on the putting green.” Nevertheless, it has been written that the author liked to play a round or two now and again. He even had his own set of golf clubs.

Hemingway once caustically wrote that, “The game of golf would lose a great deal if croquet mallets and billiard cues were allowed on the putting green.” Nevertheless, it has been written that the author liked to play a round or two now and again. He even had his own set of golf clubs.

Before WWII, Hemingway lived, fished, drank, and caroused in a Florida that was practically empty, especially south of the peninsula. With few people around, he could live a larger-than-life Anglo American, heroic existence.

Today it would be easy to accuse him of supposed “toxic masculinity” but what these radical feminist critiques of old school virtue miss is old school virtues. Before parting, my Hemingway lookalike friend and I exchanged tales. I told him about a Hemingway in Africa story related to me by the late David Read, an author and big game hunter who had met Hemingway in what is now Tanzania.

He told me a true tale of Hemingway during the Cuban revolution. It is said that a group of young American athletes were stranded in Havana as Fidel Castro’s troops were taking over the city. They witnessed Fidel’s guerrillas entering the Museums and houses of the wealthy, despoiling paintings and antiques, those “fetishes of bourgeois civilization.”

Realizing that chaos was upon the land, the athletes entered a deserted Museum carefully sliced some old pictures off their frames, rolled them up and hid them in their dormitories in the hope of retrieving them at some future date. Hemingway meanwhile helped them leave the island, making many runs with his boat to get them safely back to the Key West. It is not known what happened to the paintings.

Before the war, golf was a rich man’s sport but, after the war, it became the sport of WWII war veterans—people like my father who had grown up reading about Hemingway’s’ adventures during the Spanish Civil War, in the Key West of Florida, in Cuba and colonial East Africa. After the war, with the rise of consumer culture and the new post war prosperity, every man and his wife could live like Hemingway and initially it did not cost much to do so.

There is something calming about living on a golf course. My wife Mira and I are renting a condo on the second floor of a gracious and well-manicured golf course, a few kilometers outside of Naples, Florida to escape winter in Canada. We overlook the fourth hole and every morning, as we rise early here, we drink our coffee and watch the first group of golfers trying to sink their puts. It is our own live version of televised golf, without the commentary, without the commercials but you do get the oohs and ahs from the other players when someone sinks a good put.

My late parents, Morry and Ida, bought a condo on this golf course in the late nineteen seventies. They were not yet sixty at the time. They came here every winter for more than three decades. And so, each year sometime in December, they would pack their car, hire a driver to drive it down to Florida with their belongings and fly down for about four months of golf, tennis, going to the beach (to sit, not to swim) and socialize with their in laws and other Toronto acquaintances who had bought condos nearby.

In those days, there was no internet and long-distance calls were expensive and so my parents disappeared from sight for a third of the year. They lived to golf and golfed to live. And they did not suffer from the cold, the snow, ice, slippery streets or seemingly eternal grey skies of Canada.

A golf course is the perfect expression of what Sigmund Freud once called Civilization and its Discontents. His theory was that modern civilization demands that we give up a certain amount of libido and aggression in order to live peaceably in civil society. A golf club is the perfect example of this.

One gives up a lot of independence but in return for accepting a lot of behavioral restraints one gets beautiful landscapes, quiet evenings, splendid moon rises, perfect greens, a pro shop and a club house, plus tennis courts and numerous swimming pools as well as an onsite restaurant/dining hall.

Even if you own your condo, you pay a monthly HOA fee, homeowners association cost, to maintain the premises and provide services such as gardening and trash collection. There are rules for everything, and you are vetted. It is unlikely that anyone with a police record is allowed to join. People do not yell in public and there is rarely loud music coming from residences. It is golf and it has its own culture of quiet.

Most people rise early and go early to bed. Golf starts at 7:30 am each day, every day. Then, there are various leagues, and people compete for different kinds of championships and honors. While in her eighties, my mom sunk a hole in one that was witnessed. Her small trophy attesting to this feat lies on the mantle piece of our house.

We first visited the condo in 1984. I played golf with my dad. He took us out for dinner with my mom. Mira and I took our then four-year-old first-born son on a boat trip out into the Gulf for an afternoon. We went to the beach and collected “sand dollars.” We spent hours swimming in the various pools. We took a boat ride into the Everglades and got a taste and glimpse of the now preserved and protected Old Florida with its jaguar infested swamps crawling with alligators, snakes and deeper inland crocodiles. It was like entering Jurassic Park. We loved it.

On the golf course I marveled at the wildlife and vegetation and was warned about the “water traps” on the golf course where you may meet up with alligators. During this most recent trip I heard of two people pulled down and killed by alligators, both women, one out walking her dog and one weeding her garden.

In 1984, I could not believe that Floridians had imported the Banyan tree from India and almost half expected to see Buddhist monks meditating in its shade, as they are ubiquitous and sometimes even adorn the gardens of posh hotels and restaurants in the area. While driving, we would see who could get a direct signal from Radio Havana that allowed the rhythm and melodies of salsa and son to provide the soundtrack for our drives around the area.

In the decades to come we visited Florida a number of times. The routine was always the same and it grew on me. In those days Naples was a sleepy town of a number of multi-millionaires with their seaside mansions and the rest of the middle-class residents of Naples and owners of condos and houses on the golf courses.

Then I had no idea that the golf course is a kind of human created invasive species that like the new animals introduced into the Everglades such as Lion fish, Iguanas and Burmese pythons are altering what was once wilderness and farm land at an alarming rate.

Just the chemicals that keep the golf courses green, add hundreds of thousands of tons of fertilizer to the land in addition to those of the inland farmers. This pollution then enters the rivers and flows to the sea, exaggerating and amplifying the infectious red tides which kill millions of fish and that often make the coastal air dangerous to breathe and close beaches for days at a time. There are now 92 golf courses in and around Naples town and the number is growing.

Recently Jen Staletovich of the Miami Herald wrote the following:

Over the next 50 years, Florida’s swelling population is expected to gobble up another 15 percent—or 5 million acres—of the state’s disappearing farms, forests and unprotected green space, according to a new study released Thursday … With the population expected to reach nearly 34 million by 2070, University of Florida researchers partnered with 1000 Friends of Florida and the State Department of Agriculture to look at growth trends and urban sprawl in a state powered by land booms. What they found was startling: In Central Florida, where the population is expected to surge along the I-4 corridor, half the region will be developed if no more land is protected. Agriculture and other green spaces shrink by nearly 2.4 million acres. That could dramatically increase the flow of urban pollution into Lake Okeechobee.

So, the answer to the unstated question, “Can we all still live and play like Hemingway in Florida’s swamps, coasts and open sea?” The answer is yes, if you are willing to go to crowded beaches, make your golf reservations online and accept that the traffic on the I-75 and Route 41 will only get worse in the years to come.

As one activist environmental organization titled their report on overpopulation and runaway development in beautiful Florida there is indeed, “Trouble in Paradise” and time is running out.

In the late 1930s Hemingway sensed that the future of Florida would soon change dramatically. In his novel To Have and Have Not set in southern Florida he wrote:

…What they’re trying to do is starve you Conchs out of here so they can burn down the shacks and put-up apartments and make this a tourist town. That’s what I hear. I hear they’re buying up lots, and then after the poor people are starved out and gone somewhere else to starve some more, they’re going to come in and make it into a beauty spot for tourists.”

Prescient.

Table of Contents

Geoffrey Clarfield is an anthropologist at large. For twenty years he lived in, worked among and explored the cultures and societies of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. As a development anthropologist he has worked for the following clients: the UN, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Norwegian, Canadian, Italian, Swiss and Kenyan governments as well international NGOs. His essays largely focus on the translation of cultures.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link