by Robert Bruce (January 2020)

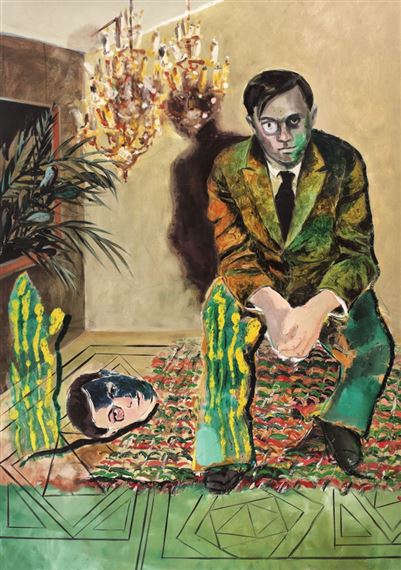

Phenomenon, Florin Petrachi, 2017

The powers of a first-rate man with the creed of a second-rate man. —Walter Bagehot

Most political careers probably do end in tragedy but if Tom Bower had opted for a less-clichéd hook on which to hang his impressive biography, Broken Vows: Tony Blair—The Tragedy of Power, he might—with the full authority of 596 meticulously researched pages—also have noted that they can also descend into venality. The penchant of Blair for the hospitality and gaudy accoutrements of the celebrity millionaires is well known and, with retirement, a shameless disregard for probity and conflict of interest has elevated him into the league of the minor super rich. Always envious of the rich and chastened by his notoriously vulgar wife, Blair has not been shy in his pursuit of reward. By the most reliable estimates, the ex-Prime Minister is worth a cool £60 million—a significant part of it extorted from audiences credulous enough to lap up platitudinous sermons on the Third Way for up to £320,000 a go, and an even larger share earned from offshored philanthropic trusts raking in eye watering commissions from corporations happy to use him as bag man in sensitive markets. These are, in themselves, perhaps no more than the baubles many former chief executives help themselves to, but for someone who traded so heavily on his moral compass this splitting of the difference between philanthropy and insider trading is fair comment, particularly when, as with a cancelled lecture for a charity the price of his much vaunted Christian conscience is a cool £320,000 for twenty minutes. This is quite a high price for virtue to run amok and, in this respect, his charity work is true to form.

In a solemn initiative, almost a billion pounds was committed to combatting truancy. The rates actually increased instead, and much of this was actually fuelled by illiterate secondary school pupils who owed their low achievements to a disastrous reversal of pedagogic standards. Government spending increased by over 78%, but any prospective benefits were more than wiped out by an abandonment of phonics and, when one looks at the flagship Academies, the disconnect between image and substance was dismally apparent. The costs of the new (needlessly overcomplicated) buildings were immense and, once these Corbusian monstrosities sprang up, they proved too clever by half. In one East London school, no one could open the windows after the caretaker unexpectedly died of a heart attack and, for all the investment in their design, they proved no less adept than their rickety state counterparts in mass producing illiterates. The middle class predictably voted with their children. No statistic spells out the failure of his educational fantasies more than the soaring private admissions of that era and, in characteristic de haut en bas fashion, Blair spared his own children from it.

Read more in New English Review:

• Politicizing Language

• The Demise of Jeremy Corbyn

• Iran Involved in 911: The Links Court Case

Governments with a corrupt messianic zeal are rarely content with prudent housekeeping, and New Labour’s pursuit of eternity was accompanied by all the Lilliputian status projects which proliferate incontinently in Third world states. If Thatcher’s enduring architectural legacy, the transformation of Canary Wharf from derelict docklands to financial nerve centre of the world had been a ruthless piece of free market triumphalism erected into glass and stone, Blair’s Millennium Dome, characteristically tasteless, overspun and ruinously overbudget, was an ugly symbolic metaphor for his tenure.

Confronted with the clear evidence of failure and desperate to secure a social legacy in his Third Term, he simply revived—in the shape of Foundation Hospitals and selective education—Tory policies he had so expensively recanted in his first. Why such wasteful and expensive interludes are necessary to arrive at basic first principles are something of a mystery but, here at least, we are not dealing with a novelty. All Left-wing governments move to the Right eventually if only for the reason that, if ideas can soar to Aeropagus, the facts of life are fundamentally conservative, the eye-watering expense of aborted socialist utopias pushing even hardened left wingers in a portentously neo-con direction. The first political figure of any weight to embrace monetarism, let it be remembered, was not Margaret Thatcher but the embattled Labour leader, James Callaghan, whose famous repudiation of the Keynesian settlement in 1976 has an eerily contemporary ring. Speaking at a sullen Labour Party conference at the height of their febrile Marxist delusions, Callaghan set out a dilemma which, for all their hubristic pretensions to have abolished boom-and-bust, New Labour was never able to escape. He said,

We used to think you could spend your way out of recession and increase employment by boosting government spending, that option no longer exists. I tell you, in all candour, that that option no longer exists. And, in so far as it ever did exist, it only worked on each occasion . . . by injecting a bigger dose of inflation into the economy, followed by a higher level of unemployment as the next step . . .

For all the fantasy economics of Britain becoming the creative workshop of the world, its sclerotic economic achievements followed a conventionally dirigiste formula which sought out problems to fit their clever solutions. To any admirer of socialist profligacy, they are no mean achievements (see them below) and Blair’s reputation as a soft Tory owed more to choreography than conviction. Labour had spent 18 years in the wilderness removing its Trotskyite leanings and Blair knew how important it was to court unpopularity on the lunatic fringes of the left. His reputation rested on a heavily and disingenuously choreographed battle to remove clause 4 from the Labour party’s manifesto, which with its romantic pledge to secure common ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange had given Labour activists a piece of nostalgia that no Labour government had ever tried to implement. In winning this pointless battle, he gained ideological cover for a breakneck expansion of the state which should not have disappointed the Left. Gordon Brown, a grim Calvinist moderniser with a Soviet autism for targets, presided over an expansion of the welfare state—which fulfilled all Hilaire Belloc’s fears of the Servile State—and its payroll vote grew exponentially. By 2004, a staggering 54% of the population received more in benefits than they paid in taxes, a material incentive to the Big Tent, and one which was aided by the relentlessly therapeutic cast of New Labour thinking. In his End of Ideology, the American sociologist Daniel Bell noted gloomily that the decline of ideology would lead to a tepid managerialism and descent into lifestyle politics—predictions which were more than fulfilled in the profusion of Orwellian units prising themselves into government and accelerating that descent into the soft enervating despotism which haunted the 19th century imagination. For all the foreboding of de Tocqueville, this parcelling out of the human spirit had not yet run its course in the 20th century if only for the fact that the welfare state did not peer too fastidiously into men’s souls. By the nineties, this reticence had been dropped, and the most insidious manifestation of this turn toward the therapeutic state was the popular notion that governments had an obligation to promote happiness[2].

To the left wing traditionalist hung up on semantics, this substitution of the language of social exclusion for the vernacular of class conflict grated but, for the new class of middle class do gooders raised to oversee these new charges, this frenetic cultivation of pathologies was a gold rush. In the new post-Diana climate of virtuous victimhood, over 60% could stake a claim to it, all of them claiming their dispensations from the bureaucracy of compassion and all hording insatiable grievances. For all the communitarian soundbites, this displacement of moral fibre with therapy drained the vitality of the third space and it was caressed by an ingspeak that fitted perfectly with his personality traits. Blair’s verbless Americanised soundbites were endless and, in time, this laboured New labour Esperanto lost the charm of irony. It is difficult after all to lampoon a vacuum and even the funny bits now seem in earnest. Asked during the ‘97 campaign whether he was English or Scottish, Blair shot back that this was “an interesting question that would have to be reviewed in government.” It doesn’t have the same ring in 2019, and maybe it should have set alarm bells ringing at the time.

The dividend for the poor and the indigent, let it be granted, were real—Blair made welfare a career option—but, for the respectable working class, the benefits, always questionable, were outweighed by the antiseptic middle class obsessions carried into the New Labour project. For all its contrived earthy populism, it was underpinned by a distinctively chattering class sensibility, and no policy highlighted its distance from the visceral anxieties of the working class than the issue of mass immigration.

The demographic re-engineering wrought by New labour is indisputable. Between 1997 and 2010, a colossal 3.6 million migrants were added to the population, and Tony Blair’s speechwriter never spoke a truer word “out of context” when he said it was driven by a desire to “rub the Right’s nose in diversity” and create multicultural facts on the ground. The issue, needless to say, could not be discussed openly—”whilst ministers might have been passionately in favour of a more diverse society, it wasn’t necessarily a debate they wanted to have in working men’s clubs in Sheffield or Sunderland,” and its costs simply compounded the initial delusions about immigration’s economic benefits.

In the postwar period, most European states opted for permanent demographic transformation as a solution for temporary economic problems, and they have been paying a heavy price since for the short-lived reprieve given to nineteenth century industries. Oldham and Lancashire have not produced textiles for fifty years but the flow of illiterates has not dried up and their claims on the welfare state present a strange anomaly for those proselytizing immigration as the saviour of public services. By the most conservative estimates, a staggering 38% of Pakistani and Bangladeshi immigrants are economically inactive and the importation of poverty into a mature welfare state has created a fissure in the social contract which any social democrat should be shying away from. No single development has done more to undermine settled communities and the cohesion of British life than mass immigration.

In overlooking this tension, Blair is no more grievously at fault than any other member of his class. To desire the solidarity and reciprocity which ultimately sustains the welfare state yet savour the lifeline of thrills and feeling of worldliness reveals a characteristically liberal schizophrenia. Not everyone however can live their life on an extended student gap year and the blowback was swift.

Once dismissed as a Tory protest vote, UKIP has (in its more polite incarnation as the Brexit party) destroyed the Labour party as the proletarian spectre—and its success highlights the progressive paradox. The left cleaves simultaneously to the values of diversity and solidarity, but citizens are less likely to be altruistic towards individuals who do not share an essential affinity for culture or values. The caveat “or values” is a critical one, and for all their misleading organic metaphors the bureaucratic imagination of New labour never got beyond clunking formulas (for Gordon Brown the spiritual force of nationhood exhausted itself in the NHS) and, truth be told, the need to define it at all belies that fatal atrophy of those civic instincts that sustain it in the first place.

One needs a big idea to paper over the cracks and meritocracy was as close as Tony Blair came. His earnestness was hardly in doubt and he deployed all the force of New Labour seriousness—a “social mobility commission”—to do the heavy lifting. Inserted into the shambles of his government, it dutifully catalogued the failures. The achievement gap had actually widened. The Sutton Trust were soon reporting that an individual born in 1958 actually had more chance of upward mobility than someone born in 1971, and most of this was attributable to a decline of state education that was, in itself, a bleak testament to the cultural permissiveness unleashed by Blair.

Social commentators often note that the right won the economic arguments and the left the cultural ones—what is less often cited is that this is the optimal outcome for the gaudy and vulgar capitalism to which we have become habituated. It suited Blair handsomely. With his dropped aitches, glotted stops, and fatuous cultural modernity, he was a natural in this low brow environment. By his own admission a self-consciously modern man, his vocabulary displayed all the rootless trendiness of Cool Britannia writ small. No Prime Minister ever had a shallower hinterland and, without the quality of moral realism he might have imbibed from the testing experiences of a hard life, his much-vaunted convictions led him dramatically astray. He hungered for the world stage and it horded its vengeance.

The only nineteenth-century figure that survived in his shallow historical imagination (and then only at the behest of his mentor Roy Jenkins) was William Gladstone whose thundering moral crusades on the international stage would have inspired Blair more than the prosaic realpolitik of Foreign Office mandarins. Frustrated by the eminent domain of Gordon Brown over social policy, Blair fled abroad in search of his legacy, and in the early years a series of cheap and morally upright interventions in Sierra Leone and Kosovo stoked up hubris. This was liberal imperialism on the cheap, and supported by a coterie of neocons, Blair dutifully scanned the globe for crusades. National interests bent the knee to humanitarian fastidiousness and, in the informal courtly atmosphere of Blair’s administration, the tendency for virtue to run amok was conspicuous.

In common with many inexperienced leaders, Blair had a weakness for over-personalising the hard realities of power politics and reducing global flashpoints to the shallowest of ethical conundrums. At the beginning of his regency, when liberal imperialism was frugal, this naiveté carried few costs; in Iraq it was nigh on disastrous. Bush, ever courteous, gave him an out but, once the drumbeats of war were sounded in Washington, the smarmy British ambassador Myer was instructed “to get as far up Washington’s arse as he could.” He stayed there and the chaos of Blair’s administration did the rest. Blair had dismantled all the institutions of cabinet government at a time when they were most needed and hubris soon beat its wings. If all previous British governments had previously marched to war with trembling and awe, Blair did it flippantly, and the costs of fighting on a shoestring were soon apparent when the first shots were fired. The poverty of equipment carried by British soldiers reduced to importuning their more lavishly equipped allies was soon apparent to the Americans. With cruel humour they nicknamed their poor relations the “borrowers,” and the lack of body armour and adequate armoured vehicles was soon to exact an unnecessarily high death toll on brave young men who were thrown into the crucible.

After a false dawn in Basra, its mission had shrunk ignominiously to the strategic nullity of “force protection” (i.e., defending itself); the British army confining itself to base whilst a medley of fanatics and criminals imposed a regime beyond even the most sadistic Baathist imagination. Faced with the end of empire in Iraq, Blair sought vainglory in a country synonymous with British imperial disaster. In Afghanistan, a tiny force was despatched to Helmand with the ludicrously unattainable objectives of opium destruction and nation building. The disasters were quick to unfold. Americans, long condescended to by “counter-insurgency” experts boring them on, Northern Ireland had been savvy enough to simply pay off the drug traffickers. The British were bolder and stirred up a hornet’s nest. It has fared no better since, and it is odd that in retirement Blair should have been further indulged in his delusions of grand strategy by being despatched to pontificate on more of the world’s simmering flashpoints.

Read more in New English Review:

• Toward Brexit: The Duffy Decade

• Tom Wolfe’s Mastery of Postmodern America

• Not Kosher: Bernie Sanders on Jews and Israel

Given the honorific title of envoy to the Quartette, Blair imagined he could bring peace to the Holy Land, and his first meeting with experts on the ground displayed all of his impatience with the earthly failings of primitive men. Recoiling from an unsolicited lecture on the economics of roadblocks, he shot back “I’ve fixed Northern Ireland.” He hadn’t—and the delusion reflected his post tragic sensibility. Peace in Northern Ireland was, literally, hard fought. I have always considered it odd that witless American senators queried whether British soldiers should “shoot to kill.” Most Americans, I expect, would expect nothing less, and the British army was proficient enough in any case. In a democracy, criminals are entitled to the protection of the law but in practice the army rightly gave these heroes of Irish American saloon bars the recognition they craved as soldiers. With all the costs. In 1987, hearing of a planned IRA attack on a deserted police station, they declined to alert the civilian authorities and a nervous police officer was politely asked to do some unscheduled overtime in a sealed bulletproof antechamber. The unsuspecting patriots turned up, let rip, and the SAS, solicitous to the last of the welfare of the policeman did the rest. Even to this day I find it difficult to grieve over it and there was a lot of this kind of armed casuistry throughout the troubles[3]. A certain hypocrisy was always necessary and it took its toll. By the nineties republicans were ready to be indulged by an American senator farmed out for his pre-memoir banalities. Blair must have known this, but he let his vanity soar and soldiered on in Judea.

Two years later, with a creaking infrastructure, more illegal settlements, a reputation for carpet bagging, and a disastrously lachrymose appearance at Ariel Sharon’s funeral to his credit, he was off with not much to boast about. If one wanted to set a very low bar one could at least be grateful that Blair’s pronouncements do not trigger the kind of retrospective horror that Jimmy Carter elicits when he opens his mouth on anything. Still, it is curious to square such an uninterrupted procession of failure with the reputation for wise counsel Mr. Blair has acquired. On December 12th, we at least got some closure on his legacy, and it is fitting that his European obsession has come back to haunt in the most intimate spaces. His old constituency Sedgehill is an ex mining town which, in its grim twilight, has horded all the drug laced poverty Americans can see in Appalachia. The poor nevertheless held their noses and voted Tory. As a working-class party, Labour is no more, and Blair’s metropolitan trendiness was as much to blame as Corbyn’s. One hopes he has no more triumphs left.

[1] Blair managed even to shock the Nigerian government in 2015 with his conflicts of interest

[2] The court influence of pop psychologists like Oliver James who argued the country needed to be drugged and counselled into a state of infantilised euphoria depicted in Huxley’s Brave New World was significant.

[3] The British army’s rule of engagement stipulated terrorists had to be armed, and lives in imminent danger

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

_____________________________________

Robert Bruce is a low ranking and over-credentialled functionary of the British welfare state.

More by Robert Bruce.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link