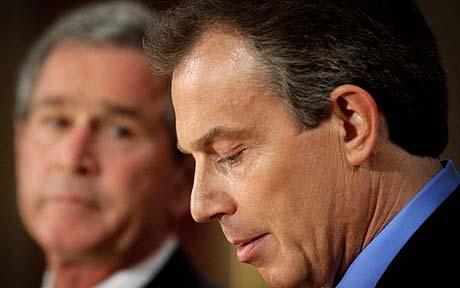

Tony Blair’s Iraq War Confessions

by Paul Austin Murphy (November 2016)

This piece is primarily based on Tony Blair’s own words on the 2003 Iraq War. Most of the quotes come from Blair’s autobiography, My Journey. The title is partly ironic if one bears in mind that Blair did indeed – fairly recently (e.g., October 2015) – confess his culpability in regards to Iraq and what went on to happen there post-2003 (e.g., the rise of the Islamic State, etc.). Nonetheless, these aren’t the confessions I’m referring to.

Much of what follows consist in quotation; with additional commentary and some analysis. Indeed because there are so many quotes by Blair in this piece, I didn’t feel the need to write the clauses ‘Blair said’, ‘Blair wrote’, etc. before every quotation. I expect the reader to realise that the words in quotation marks are almost always Blair’s. In addition, although many quotes provoke commentary or analysis, a few don’t. Thus the reader should know that such quotations don’t necessarily come either with implied agreement or with implied criticism.

As just stated, this piece is neither entirely positive towards Tony Blair nor entirely critical. It is, nonetheless, largely a reaction to the often mindless – and ultimately left-wing – criticisms of the former British Prime Minister and his decision to intervene militarily in Iraq in 2003.

Blame

What is surprising is the amount of people who fall into the trap of blaming others for Arabic violence and Islamic fanaticism – or at least they’ve done so in the case of the Iraq War. Has everyone bought into this “narrative” (a favourite word of Leftists) on Iraq?

So who was – and still is – to blame for the violence in Iraq? Not ISIS, Iraqi Muslims, Shia/Sunni militia and terrorists, Baath party members, etc. Not in the slightest. Muslims, it seems, are never to blame when in comes to the racist Left; which sees all Muslims as children who are incapable of behaving humanely or decently. Instead it’s all the fault of Blair, or Bush, or the “neocons,” or global warming (as The Guardian and Noam Chomsky have it), or whomever.

Yes, it may be absolutely true that Tony Blair shouldn’t have intervened in 2003. It may also be true that he’s power-mad lunatic who wanted (or still wants) to go down in history as a great statesman. Nonetheless, what he did, he did some 14 years ago and the violence is still with us. Sure, we stayed in Iraq until 2009/11; though in 2007 Blair resigned and then more or less disappeared from the political scene.

***********

Tony Blair attempts to legitimise his position on Iraq by using a quote from an Iraqi woman – formerly a victim of Saddam Hussein. According to Blair:

“I still keep in my desk a letter from an Iraqi woman who came to see me before the war began. She told me of the appalling torture and death her family had experienced having fallen foul of Saddam’s son. She begged me to act.”

Blair continues:

“After the fall of Saddam she returned to Iraq. She was murdered by sectarians a few months later. What would she say to me now?” (479)

As I will say a few times in this piece, many haters of Blair will simply say that he’s lying about this. (After all, Blair is “Bliar,” isn’t he?) The basic gist here is that Blair thought he was doing good. Nonetheless, he accepts that his actions had disastrous consequences. Thus are critics of Blair critical because he couldn’t predict the future? Or are people critical because they believe that, in his heart of hearts, Blair knew that mass violence and terrorism would be the result of the Iraq intervention in 2003?

Tony Blair also confronts Saddam’s crimes head-on when he quotes himself speaking in Glasgow in October 2002 (on the same day as the mass protests). He told the audience that “’tens of thousands of political prisoners languish in appalling conditions in Saddam’s jails and are routinely executed’” (426). He also said that “in the past fifteen years over 150,000 Shia Muslims in southern Iraq and Muslim Kurds in northern Iraq have been butchered.” Finally, he said that “up to four million Iraqis in exile round the world including 350,000 now in Britain.”

Following on from that, and in the same speech, he singles out the hypocrisy of the “anti-war” Left. He said:

“There will be no march for the victims of Saddam, no protests about the thousands of children who die needlessly every year under his rule, no righteous anger over the torture chambers which if he is left in power will be left in being.” (426)

Of course the revolutionary – and even moderate – Left didn’t march against Saddam Hussein. Saddam had brown skin and he didn’t rule a “Western capitalist state.” Thus his crimes were of no interest to most – if not all – Leftists. That’s unless links could be found which connected Saddam to the UK, US and the West generally. And, of course, links were made; though they were made primarily after the intervention of 2003.

Tony Blair also argues that, as philosophers put it, there was no necessary connection between removing Saddam Hussein and the mass violence which followed (mainly a couple of years later, according to Blair). As Blair himself puts it:

“The notion that what then happened was somehow the ineluctable consequence of removing Saddam is just not right. There was no popular uprising to defend Saddam. There was no outpouring of anger at the invasion. There was, in the first instance, relief and hope.” (465)

What ruined all this was that “tribal, religious and criminal groups [decided] to abort the nascent democracy and try to seize power” (465). What’s more, Blair believed that “if the terrorists could cause chaos, the resulting fear and security clampdown would become a signal that the mission had failed.” (465)

Again, should Blair have known all this would have happened in a (typical?) Arab country?

Thus not all the blame for the Iraq War can be placed in the hands of Blair and Bush… at least not according to Blair himself. He tells us that “it is instructive to read the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998 passed by President Clinton” (385). In more detail:

“It was then that US policy became regime change, but it did so – as the Act makes clear – because the WMD issue and Saddam’s breach of UN resolutions.” (385)

Of course it can now be said: But Clinton didn’t invade Iraq. Blair and Bush did! We can also ask if Clinton would have intervened in Iraq had he the chance and/or reason to do so. I believe that at some point, had he retained power, Clinton might well have invaded Iraq. (Let’s not forget here that Clinton had already bombed Iraq in 1998).

United Nations Resolutions

I always found it strange when the anti-war Left said, and still say, that the Iraq intervention was “illegal.” Firstly, many people say that without having any idea what they mean by the word “illegal” (in this context at least). Secondly, if the Iraq intervention was illegal, it was illegal according to the United Nations. This is odd: the vast majority of the anti-war Left reject the UN for being, amongst other things, a “cosy capitalist club.” (One should ask, for example, the Stop the War Coalition what it thinks of the UN outside the context of the Iraq intervention and, of course, Israel.)

Another cliché at the time was that both the “international community” (meaning the community of nations) and the people were against the war. This was far truer of the people than it was of the international community. In Tony Blair’s words, when it came to Europe, “thirteen out of the twenty-five members were in favour” (423). (Notably, “Spain and Italy both supported action.”) In addition, “Japan and South Korea also rallied”; as did Australia.

Despite all that, it’s still clear that, right from the start, Blair did indeed see action as necessary. But that shouldn’t have been a surprise to anyone who had listened to his 18th of March 2003 debate in the House of Commons. In that debate Blair said the following:

“To fall back into the lassitude of the past twelve years; to talk, to discuss, to debate but never to act; to declare our will but never to enforce it; and to continue with strong language but with weak intentions – that is the worst course imaginable.” (438)

Blair’s Commitment to UN Resolutions

Despite his grand plans, Tony Blair also often talked about both the US and UK needing to abide by UN resolutions. Or at least to do so in specific cases.

How does “nation-building” and dreams of “global change” fit in with with Blair’s claims that he has “never put the justification for action as regime change” and that “[w]e have to act with the terms set out” by UN resolutions (439)? This quote is a specific reference to Iraq in the pre-2003 period. Nonetheless, how does talk about a lack of commitment to “regime change,” as Blair put it, square with Blair’s “idealism” and his foreign policy generally? In many cases, of course, regime change will bring about immediate and large results; though often negative ones.

Blair himself gives the reasons as to why he went to war with Saddam Hussein in 2003. He asked: “What did I truly believe?” He answered his own question thus:

i) “That Saddam was about to attack Britain or the US? No.

ii) “That he was a bigger WMD threat than Iran or North Korea or Libya? Not really, though he was the only leader to have used them.

iii) “That left alone now…. he would threaten the stability of the region? Very possibly.

iv) “That he would leach WMD material and provide help to terrorists? Yes, I could see him doing that.

v) “Was it better for his people to be rid of him? For sure.

vi) “Could it be done without a long and bloody war? You can never be sure of that…

vii) “Would a new Iraq help build a new Middle East? I thought that possible.

viii) “Did I think that if we drew back now, we would have to deal with him later? That I thought was clear: yes….” (413)

Of course a person who already detests Blair will think that all the above is a big bunch of “Blairite nonsense.” Nonetheless, it is an interesting list of both good and bad reasons to remove Saddam Hussein:

i) In order to accept i), one would have to believe what Blair had to say on the 45-minute document, WMD, etc.

ii) No one can deny that Saddam actually used chemical weapons against the Kurds and the Marsh Arabs (Shia Muslims) in the south of Iraq. There is absolutely no doubt that if he had such weapons, he would have used them again.

iii) There is little doubt that he might have re-invaded Kuwait. In addition, he might have gone to war with Saudi Arabia and possibly resume a state of war with Iran. He would have continued to fund Palestinian terrorists too.

iv) He did fund terrorists, as stated in iii) above.

v) That seems obviously true. However, he did have strong Sunni Muslim support; though not all Sunnis – or even the majority – were his friends. Admittedly, he also – through his dictatorship, torture and imprisonment – put a lid on sectarian violence.

vi) Here Blair is admitting that he knew the invasion could have led to a long war with many casualties.

vii) This is an explicit reference to Blair’s “neoconservative” stance on these matters. Perhaps he genuinely believed that he could help “build a new Middle East” by regime change in Iraq. Although “this was a possibility,” it was highly unlikely if we consider the nature of Arab states and their long history of autocracy and dictatorship; as well as the sectarian (Sunni/Shia) undercurrent which was, I think, bound to have been unleashed by an invasion. Again, should Blair have known all that? Well, as a neoconservative on these matters, he surely mustn’t have been aware of the disastrous consequences of his actions. (The neocon position was that most Muslim Arabs were yearning for a Western-style democracy.)

It’s still crystal clear that Saddam would have remained a vicious thug and a menace to the region. Nonetheless, did that directly concern the UK and US? And even if it didn’t directly concern us (whatever that may mean), should we have invaded Iraq in 2003?

Resolution 1441

Tony Blair’s basic point is that a second UN resolution wasn’t legally necessary. Yet Blair also said that “[f]or me too, the prospect of a second UN resolution was central” (421). Blair goes on to say that it “bestowed more legitimacy, it was true.” Though “whether we got a second resolution or not basically depended on the politics in France and Russia” (433).

Despite all that, Blair also claims that “[w]e had left unresolved the issue of whether a breach of Resolution 1441 was in and of itself a justification for action.” On Resolution 1441, Saddam’s cooperation “fell short of what Resolution 1441 demanded.”

Blair happily admits that Resolution 1441 (in November 2002) “didn’t explicitly state that military action was to follow” (422). Thus, those against the war believed that “any military action required yet another resolution” (422). Though, as already stated, had there been a further resolution, it would have been vetoed by both France and Russia. That must have meant that many people who were against the war would still have been against the war had there been another resolution. They were again intervention/war – full stop!

Despite saying that “the prospect of a second UN resolution was central,” Blair also informs us that “[w]e had acted with UN authority in Kosovo” (433). What’s more, “[i]t would have been highly doubtful if we could ever have got UNSC [UN Security Council] agreement for either Bosnia or Rwanda.” Indeed Blair “never even thought about it for Sierra Leone” (433).

None of that mattered, however, because the “truth [was] that the international community jointly agreed 1441 and then got buyer’s remorse once it became clear Saddam was still not really playing ball” (422). In other words, for many in the “international community” the threat of military action against Saddam was always empty. These people hoped to call Saddam’s bluff. But, of course, they ultimately failed.

The Left – and indeed some on the Right – demanded a second UN resolution. Most of these people, at the time, knew that President Chirac and President Putin would have vetoed the second resolution too! By the 13th of March 2003, the French “were starting to say that they would not support military action in any circumstances, irrespective of what the inspectors found” (431).

Thus, in this respect, talk of a second resolution was a con-trick. Or as Blair himself puts it:

“If people disagreed with war, they tended to think a second UN resolution specifically and expressly authorising military action was legally necessary; if they agreed with removing Saddam, they didn’t.” (421)

If there had been a second resolution, Blair claims that “if France has not threatened to veto any resolution authorising action, we would have probably got a second resolution” (436). (Blair doesn’t mention Russia here: the resolution could have been vetoed by a single UNSC member-state.)

Resolution 678

So what of that previous UN resolution?

According to Blair, the “previous UN resolution in the early 1990s specifically authorised the use of force to make Saddam comply with the UN inspection regime” (421). According to to the UN itself, Resolution 678

“authorised Member States to use all necessary means to uphold and implement its Resolution 660 (1990) of 2 August 1990 and all relevant resolutions subsequent to Resolution 660 (1990) and to restore international peace and security in the area.” (421)

Importantly, Resolution 678 (just quoted) “was still extant” in early 2003 – just before the war. This meant that “from the outset the authority to use force remained in being” (421). Despite that, Blair admits “that because of the passage of time, we should have a fresh UN resolution specifying that Saddam was in breach of the UN resolutions in order for 678 to be the basis of further action” (422).

The “Dodgy Dossier”

Looking back at the “dodgy dossier” when it was first released in September 2002, Tony Blair says that it was considered “dull and not containing anything new” (406). Nonetheless, it was indeed the case that the “infamous forty-five minutes claim was taken up by some of the media on the day but not referred to afterwards” (406). Despite that, it “was not even mentioned by [Blair] at any time in the future” (406). Blair continues:

“Of the 40,000 written parliamentary questions between September 2002 and the end of May 2003 when the BBC made their broadcast about it, only two asked about the forty-five-minutes issue. Of the 5,000 oral questions, none ever mentioned it. It was not discussed by anyone in the entire debate of 18 March 2003.”

In fact the … didn’t hit the fan until the 29th of May 2003 when “the BBC’s Today programme contained as its top story revelations from its defence correspondent Andrew Gilligan.” Gilligan “focussed on the forty-five-minutes claim in the September 2002 dossier” (452). This was some two months after the Iraq invasion. Thus, Blair says, “the idea we went to war because of this claim is truly fanciful” (406).

In any case, Blair happily admits that the “claim turned out to be wrong.”

What about the dossier itself? It was the work of the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC). Tony Blair says that the dossier “was an accurate summary of the material” (406). As for Blair and Alistair Campbell’s contribution to it, Blair states that “[n]either myself nor Alastair wrote any of it” (406). That isn’t entirely true because, according to Blair himself, he “wrote the forward only” (406).

In March 2002, the JIC did indeed say its intelligence on Iraq was “sporadic” and “patchy.” Nonetheless, it said – Blair quotes – that “it is clear that Iraq continues to pursue a policy of acquiring WMD and their delivery means” (406).

Blair admits that “[t]here was evidence given to the Chilcot Inquiry that Saddam might not be able to assemble WMD quickly” (407). Blair says that “[t]his was reported in the media… [and that he] was being warned that the threat was less than supposed” (407). Blair, on the other hand, said that “the intelligence was that Saddam had taken measures to conceal his programme” (407). What’s more, “the overall impact of the intelligence was not that he had given up his programme but that he was hiding it from inspectors” (407).

Dr David Kelly

This is where Dr David Kelly enters the picture.

The “dodgy dossier” was debated by the Ministry of Defence. Blair claims that this was “unknown to [him], or to the Secretary of State, or indeed to the JIC” (453). Dr David Kelly did know about the debate because he was part of it; even “though [he was] not directly responsible for the dossier.” Kelly was invited to the debate because he was regarded as a Ministry of Defence intelligence expert.

According to Blair, it wouldn’t have been a big deal if the BBC broadcast had simply claimed “that the intelligence was wrong on the forty-five minute” (453). Andrew Gilligan went further than this. Blair quotes Gilligan as saying that “the government probably knew that the forty-five-minute figure was wrong even before it decided to put it in” (453). This is where the “sexed up” business came in. Blair goes on to quote Gilligan saying that “Downing Street… a week before publication ordered it to be sexed up to be made more exiting and ordered more facts to be discovered” (453).

Gilligan went even further than that. He went on to say, in an article in the Mail on Sunday, that “Alastair was the author of the whole claim, i.e. invented it” (454). As we’ve seen, Blair claims that the JIC first stated the claim and then it was more or less ignored by everyone else… until the BBC broadcast of the 29th of May 2003.

It was even the case, according to Blair, that Dr Kelly “denied making the allegation”; though he did indeed “[admit] to talking to Gilligan” (458). Indeed in a 15th of July interview, Kelly denied he could have been the source of the Gilligan story since he “disputed it” (456). He also said that “he had never thought or said that Alistair was responsible for inserting stuff into the dossier” (456). On the dossier as a whole, Dr Kelly, in his own words (though quoted by Blair), thought it was a “a fair reflection of the intelligence that was available and presented in a very sober and factual way” (456).

The public didn’t find about Dr Kelly’s role until early July, 2003. That was over a month after the first BBC broadcast on the dossier.

Even years after the dodgy dossier scandal first hit the public at large, Blair says that “allegations that we were a government of ‘spin’ are made”. He added that when “I ask for examples, the dossier is always the one that figures” (463). But, as Blair points out, “there was an inquiry (one of four) lasting six months that found the opposite” (463).

Blair’s Iraq Timeline: 2003 to 2005/6

Tony Blair argues against the position that “what happened was somehow the ineluctable consequence of removing Saddam” (465). That position “is just not right.” Moreover, “[t]here was no popular uprising to defend Saddam” and “[t]here was no outpouring of anger at the invasion.”

It’s seems obvious – though perhaps it needs to be spelt out – that the various terrorist groups in Iraq at that time wanted chaos. Like Leftist revolutionaries, Islamic extremists know that peace and democracy don’t serve their purposes. Chaos does. And, yes, perhaps Blair should have known that.

2003 to 2005

As everyone knew at the time, and many still remember today, “from 19 March [2003] to the effective end of Saddam’s government was less than two months” (447).

In early 2003 (from March to May), Tony Blair says that “the reception accorded to the forces, if not that of garlands of flowers, was certainly more like that extended to a liberating force than an occupying one” (449). Blair goes into more detail. He writes:

“Towards the end of April [2003], a million Shia pilgrims attended the main Shia festival in Karbala, something Saddam had forbidden to them.” (449)

Here again those against Blair can say that he’s lying… again. Either that or he simply misconstrued the reception the forces received from many Iraqis (specifically from Shia Muslims and Kurds).

More generally, even by May of 2003, Blair claims that the “humanitarian disaster had not happened” (450). By that he meant that the “oilfields had been protected” and the “resistance of Saddam elements had crumbled”. Indeed: “The warnings of doom had been wrong.” (450) Blair admits, however, that between March and May 2003, 8,000 Iraqis had died.”

Even after May 2003 Blair claims things were “relatively benign” (464). He admits that there was “looting and some violence; some attacks on coalition forces.” Nonetheless, these things “were containable.”

By July 2003 coalition forces and the UN “convened an Iraqi Governing Council” (464). This Council “had twenty-five members: thirteen Shia, eleven Sunni, one Christian”. Since Shia Muslims outnumbered Sunni Muslims 65% to 32%, it’s not surprising that they had more members than the Sunnis. It also needs to be remembered that Shia had almost zero political power under Saddam. (It will be noted that Kurds weren’t represented in the Iraqi Governing Council at this time.)

Blair goes into more detail about the period May 2003 to July 2003. Here again Blair claims that “things were moving to a new state of rebuilding the country” (464). What Blair meant by this is that “schools [were] reopening, hospitals functioning and police reporting for duty.” What’s more, “in Basra at the end of June, 17,000 students at the universities took their exams normally.”

Moving on to July 2003, in Baghdad “the traffic was busy” and Mosul and Kirkuk “were generally clam” and the “Kurdish areas naturally felt liberated” (465).

Clearly, it can now be said that Blair has cherry-picked the good things; rather than, say, explicitly lied about them.

The Iraq election was, of course, the most important event in of 2005.

At the end of January, 2005, Iraqis elected the Iraqi Transitional Government in order to draft a permanent constitution. There was some violence and a large-scale Sunni boycott. However, most of the eligible Kurds and Shia Muslims voted.

2005 to 2007

Tony Blair challenges the many opponents death-count of the Iraq War. Or at least from its beginning to 2005/6 or 2009. He writes that the usual figure which was banded around was 500,000 or 600,000 between, as I said, 2003 and 2009. The Brookings Institution, which came to a similar figure as the anti-war Iraq Body Count group, says that the figure was “just over 100,000 and 112,000” (380).

It’s here that Blair has a very strong point which is ignored by many (or nearly all) anti-war protestors and commentators. Blair claims that 70,000 Iraqis were the victims of the “sectarian killings” which occurred between 2005 and 2007. More directly, Blair blames al-Qaeda and “Iran-backed militia” for much of this.

This won’t matter to most anti-war protestors because they’ll simply say that Blair and Bush started the war and that these deaths wouldn’t have occurred had Saddam Hussein been left in power. (Actually, the words “had Saddam Hussein been left in power” are often hinted at, rather than explicitly stated.) This is a very poor political and philosophical position. For a start, should Blair have known in advance that Iraqis were so keen on killing each other? (One thought is that had Blair ever said that Iraqis would kill each other en masse he would have been classed as a “racist” by the anti-war Left.)

There’s an added problem with this view that Blair and Bush. were responsible for Iraqis killing Iraqis. That is, that the civil war slaughter was actually an unintended consequence of the intervention. Or, at the least, that it might have been the case that Blair had had no idea what would happen. Perhaps he should have known. Nonetheless, the philosophically inept posit on causation also disregards this early period of relative peace – roughly, from 2003 to 2005. That’s two years’ of relative peace before Shia and Sunni Muslim terrorists and militia started killing each other and killing civilians. Indeed, unsurprisingly, Blair has many other things to say about this early period of the war.

As stated, the Iraq War downturn, at least according to Blair, was 2006. That’s when the body-count began to rise – three or so years after the initial intervention. As Blair puts it:

“By mid-2006… it was clear that the Iraq campaign was not succeeding…. Articles were appearing comparing the situation unfavourably to that under Saddam.”

More relevantly:

“In 2006, according to the Iraq Body Count, almost 28,000 Iraqis died and almost as many were to die in 2007. Most were dying in terror attacks and reprisals, killed not by US or UK soldiers but in sectarian violence. But we, as the coalition forces, got the blame.” (472)

Clearly here again those who are against Blair won’t care that most of these deaths were sectarian in nature. If Blair hadn’t invaded, they’ll say, these things wouldn’t have happened. And, I suppose, that’s true. Nonetheless, there was always the possibility of a Shia insurrection under Saddam, as there had been in 1991 and 1999. In any case, if all the bloodshed was a result of “invasion,” then why did it take three years or so for the worst of it to kick-in?

Blame: Al-Qaeda and Iran

As stated, Tony Blair blames much of the post-2003 Iraq violence on al-Qaeda and Iran. He tells us:

“Suppose we had not had al-Qaeda and Iran as players in the drama would it have been manageable? Without hesitation, the answer is yes.”

The anti-Blairites – even if they accept that – will still see Blair as being the main culprit. After all, if the invasion had never have happened, and Saddam had remained in power, it’s indeed the case that there would have been few – or even no – terrorist bombings in Iraq.

Of course very many commentators have said that the claims that al-Qaeda were in Iraq was false.

Firstly, we have to decipher what Tony Blair knew pre-2003; and then what he knew post-2003.

Blair tells us that “[i]t later emerged that al-Zarqawi, the deputy top bin Laden, had had meetings with senior Iraqis and established a presence there in October 2002” (384). However, Blair also says that “[i]t is also correct that some in the US system thought there was such a link”. Blair continues: “It is also correct that there was strong intelligence that al-Qaeda were allowed into Iraq by Saddam in mid- 2002…” (384)

Clearly, then, the “US system” (as Blair puts it) claimed to have knowledge of al-Qaeda in Iraq before the invasion of March 2003. Blair, on the other hand, uses the past tense when he says “it later emerged” that al-Zarqawi had a presence in Iraq. Two questions arise from this.

i) Did Blair accept the intelligence from the US system and see it as a reason for intervention?

ii) Why was Saddam so keen on having terrorists within his country?

Most Arab states, from Saudi Arabia to Jordan, come down hard on both home-grown terrorists and terrorists within their territory from other countries. In other words, what would Saddam have wanted or gained from al-Qaeda? (At least when he sent money to Palestinian suicide bombers, those bombers did their work a long way from Iraq itself.)

Blair isn’t the only one to partly blame al-Qaeda and Iran for much of the bloodshed. Take the example of Kimberly Kagan, whom Blair refers to in his autobiography. Kagan is a military historian who wrote The Surge. In that book, as quoted by Blair, she “describes how over time al-Qaeda and Iran began to work together to unhinge the fragile democratic structures of Iraq.” More incredibly, “by the middle of 2007, Iran was both funding and training al-Qaeda operatives.” This isn’t a surprise because neither Iran nor al-Qaeda wanted a “Western-style democracy.” Thus collaboration made sense to them. Again, these Sunni-Shia collaborations occurred pretty late in the day – three/four years after the intervention in 2003. (Indeed despite the war between Shia and Sunni Islam, both Sunni and Shia have collaborated into order to “defeat the Zionists” or fight against the West. That’s partly why Iran has funded and supported Sunni Hamas against Israel.)

Blair offers a different set of reasons as to why Iran didn’t want democracy in Iraq. Blair claims that “[i]f Iraq were to settle down as a reasonably well-functioning democracy, Iran would not last long in its present state” (469).

Tony Blair’s Neoconservative War?

Many people will remember the excessive use of term “neocon” in both the lead up to and during the Iraq War. As with the word “neoliberalism” from around 2008/9 onwards (a word popularised by, amongst others, Naomi Klein), it virtually had no content most of the times it was used. This isn’t to say that “neocon” has no content; only that many of those who used this word simply did so as a term of abuse or to implicate what’s often called the “Jewish influence” on such affairs.

Defining the Word “Neocon”

Was Tony Blair a “neocon: before the Iraq war of 2003? Blair doesn’t and didn’t think so.

Firstly, he tells us that he “never quite understood what the term ‘neocon’ really meant” (389). He then tells us what other people mean by the word neocon: “It means the imposition of democracy and freedom…” (388)

So Blair does, after all, know what the term “neocon” means. Despite that, Blair’s problem with the term is that he thinks “the imposition of democracy and freedom” is an “odd characterisation of ‘conservative’” (388). In other words, Blair knows what many other people mean by “neocon”; though he thinks it’s a misuse of the word “conservative.” Indeed! Many conservatives would agree with Blair on this one!

Blair also writes:

“It [Blair’s position on foreign policy] also utterly confused left and right until we ended up in the bizarre position where being in favour of the enforcement of liberal democracy was ‘neoconservative’ view, and non-interference in another nation’s affairs was ‘progressive’.” (225)

Blair elaborated on the imposition of democracy and freedom motive by saying that

“what [neoconservatism] actually was, on analysis, was a view that evolution was impossible, that the region [the Middle East and elsewhere] needed a fundamental reordering.”

We’ve seen that Blair completely endorsed that position.

Thus although Blair has pedantic problems with the word “neocon,” he still knows it represented the position that “evolution was impossible, [and] that the region [the Middle East] needed a fundamental reordering” (388). Importantly, Blair accepted this neocon position – and he did so wholeheartedly. Indeed he repeatedly endorses that position throughout much of his autobiography.

Tony Blair could never have put the neocon foreign-policy position (if that’s what it is) better than when he said the following:

“The categorisation of policy into foreign and domestic has always been somewhat false. Plainly a foreign crisis can have severe domestic implications, and this has always been so.” (223)

And in order to deal with these “foreign crises,” Tony Blair argued for a “new geopolitical framework.” That new geopolitical framework, according to Blair, “requires nation-building.” More relevantly, it

“requires a myriad of interventions deep into the affairs of other nations. It requires above all a willingness to see the battle as existential and to see it through, to take the time, to spend the treasure, to shed the blood….” (349)

As stated, “nation-building” is a vital part of neoconservatism and Blair was very keen on such a thing. He believed/believes that the UK and US were/are in a “position of nation-builders.” That means that the UK and US “must accept that responsibility and acknowledge it and plan for it from the outset.” Though, he believes, none of this really occurred “in respect of Iraq” (474).

So whatever you may say about Tony Blair, he is – and was – honest about his championship of an interventionist foreign policy. Indeed he revelled in it.

Blair traces the birth – or rebirth – of neoconservatism to “George Bush’s State of the Union address in January 2002” (388). That was when Bush made his “famous… ‘axis of evil’ remark, linking Iran, Iraq, Syria and North Korea” together as fellow offenders.

Neoconservatism, of course, pre-dates 2002. Nonetheless, that date – or speech – was an important one in the progression of neocon doctrine.

Part of Blair’s acceptance of the neocon position (even if he didn’t like the term itself) can also be seen in his Chicago Speech of 1999 (i.e., only two years after becoming UK Prime Minister). In that speech

“I had enunciated the new doctrine of a ‘responsibility to protect’, i.e. that a government could not be free to grossly to oppress and brutalise its citizens.” What’s more, Blair had “put [this] into effect in Kosovo and Sierra Leone” (400).

Of course this is an impossible doctrine to adhere to. There are simply too many “oppressed and brutalised” peoples in the world today. That means that neocons, and others, will need to pick and choose which people to protect. It also means that reasons other than oppression and brutalisation will need to be taken into account: such as the UK or US’s own safety and the lives of our own soldiers. And, yes, financial/economic and other less edifying matters will also enter the equation.

Blair himself says that he knew, at the time, that “Saddam could not be removed on the basis of tyranny alone” (400). What gave Blair a stronger reason than resisting tyranny, apparently, was “non-compliance with UN resolutions” (400). Nonetheless, it can be said that those UN resolutions on the subject of Iraq and Hussein existed in part for reasons of his tyrannous rule (which included the his past use of WMD).

Blair, in his autobiography, also comes clean about what can be called extreme neoconservatism. Or, at the very least, he comes clean about Dick Cheney.

Blair tells us that Cheney “was unremittingly hard line.” He was a man who “was not going down the UN route” (408). Then Blair becomes very honest indeed. He writes:

“[Cheney] would have worked through the whole lot, Iraq, Syria, Iran, dealing with all their surrogates in the course of it – Hezbollah, Hamas, etc. In other words, he thought the world had to be made anew, and that after September 11, it had to be done by force and with urgency. So he was for hard, hard power. No ifs, not buts, no maybes.” (408)

Despite Cheney, we can now ask that if neocon foreign policy was right in the case of Sierra Leone, Afghanistan and the Balkans (to cite Blair’s own positive – in his eyes – examples), why shouldn’t the UK and US “work through” Iraq, Syria and Iran – along with Hezbollah and Hamas – too? What’s the important and fundamental difference between Sierra Leone and Iraq, Afghanistan and Iran; or the Balkans and Syria? What’s more, what’s the fundamental difference between, say, Boko Haram/al-Shabaab and Hezbollah? Or, more relevantly, between the Islamic State (IS) and Hamas? After all, they’re all Islamists and terrorists fighting to establish an Islamic state in the lands they control – as well as elsewhere.

Therein lies a fundamental problem with neocon foreign policy: possible intervention overload or overkill.

Afterwords: Blame Again

It can easily be argued that the violence in Iraq is still happening not because of Blair, Bush, the Balfour Declaration or the “neocons.” In my view it’s mainly – though not exclusively – to do to with Islam, Arab tribal culture (which is itself largely a product of Islam) and the fact that violence has always been the first resort in Iraq and in most other Muslim countries. And that was the case well before Blair, Bush or any other Western leader made their mistakes. It ultimately goes back 1,400 years.

Are Muslims children? Do they have free will and conscience? Are they responsible for their own actions? Yes? Good. Then we should stop blaming all that Muslim violence and Islamic fanaticism on Western leaders/states and Western actions. We should stop the (inverted/positive) racism. Adult Muslims are responsible for what they do; just as all adults are.

Despite all that, the Left also conveniently forgets that the “invasion” in 2003 was partly in response to prior Iraqi violence. In other words, there was massive violence in Iraq before 2003. And there has been massive violence in Iraq after 2003.

You see, many Muslims in Iraq didn’t want Western-style democracy. They didn’t want “Western values.” Full stop. Very many Muslims – even the vast majority – in Iraq (as elsewhere) still want one of two things:

i) Either an Islamic Shia/Sunni state.

ii) Or a “strong man” leader to keep sectarian chaos under raps and, therefore, the state in one piece. (Someone like Saddam Hussein, perhaps. Or, maybe, someone like Bashar al–Assad or the Egyptian leaders Hosni Mubarak and now Abdel Fattah el-Sisi.)

So what we have here, it can be said, is an Arab problem – not just an Iraqi problem. What’s more, what nearly all these ethnic groups, militia and terrorists (the ones involved in violence) have in common is, yes, Islam.

_____________________________

Paul Austin Murphy lives in West Yorkshire, England. He’s had articles published by American Thinker, Think-Israel, Liberty GB, Broadside News, Human Events, Faith Freedom, etc.

He also runs the blogs Paul Austin Murphy on Politics and Paul Austin Murphy’s Philosophy.

To comment on this article, please click here.

To help New English Review continue to publish interesting articles such as this, please click here.

If you have enjoyed this article and want to read more by Paul Austin Murphy, please click here.