Two Aspects of Jorge Luis Borges

Translated from the Spanish by

Evelyn Hooven (July 2019)

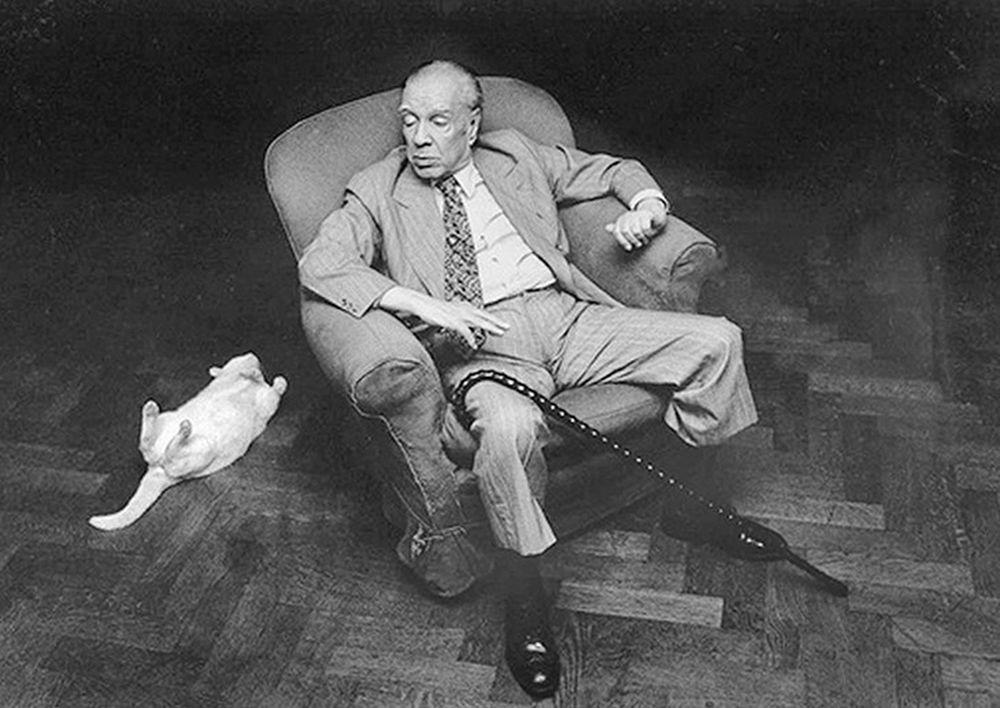

Jorge Luis Borges and Kitty (photographer unknown)

The poet, so frequently, of quest and affirming praise becomes

in “Remorse” the voice of assertive, extravagant self-dismissal

and accusation, meriting grandiose punishment. The perspective

goes far beyond any more traditional art-life dichotomy or regret

for paths untrodden. Such vehemence of culpability remains

disquieting even if one truthfully receives it as an aspect of Borges’

willingness to entertain all possibilities, even rejection of his own

(mighty) poetic faculties for not serving, as intended by his forbears,

worldly daring and valor.

Trying, in “End,” to define his physical locale quickly becomes

a total quest to contain the burden of memories and to locate his

own voice. We inevitably recognize familiar Borges terrain in the

entreaty against oblivion.

Remorse

I have committed the worst of sins

that a man can commit. I have not been

happy. Let glaciers of oblivion

encircle and drop me, merciless.

My parents begot me for the game—

daring and lovely—of life itself,

for earth and water, for the air and fire.

I cheated them. I wasn’t happy.

I didn’t carry out their youthful will.

My mind applied itself to the obstinate

symmetries of art, that can interweave nothingness.

Valor was my legacy. I wasn’t valiant.

Always it’s at my side. It never leaves me,

the shade of having been a desolate man.

El Remordimiento

He cometido el peor de los pecados

que un hombre puede cometer. No he sido

feliz. Que los glaciares del olvido

me arrastren y me pierdan, despiadados.

Mis padres engendraron para el juego

arriesgado y hermoso de la vida,

para la tierra, el agua, el aire, el fuego.

Los defraudé. No fui feliz. Cumplida

no fue su joven voluntad. Mi mente

se aplicó a las simétricas porfías

del arte, que entreteje naderías.

Me legaron valor. No fui valiente

No me abandona. Siempre está a mi lado

la sombra de haber sido un desdichado.

End

The ancient boy, a man without history,

an orphan who might have been someone dead

makes use in vain of the deserted homestead.

(It was for two, today it’s for memory.

It is for two.) Under the harsh fate,

nearly lost, the man in pain looks for

the voice that was his voice. The miraculous

would be no more irregular than death.

They weigh him down interminably

the trivial and the sacred he recalls,

and they’re our destiny, these mortal

memories vast as a continent.

Make me, I ask of God, No One or Maybe,

boundaryless, not some oblivion.

El Fin

El hijo viejo, el hombre sin historia,

el huérfano que pudo ser el muerto,

agota en vano el caserón desierto.

(Fue de los dos y es hoy de la memoria.

Es de los dos.) Bajo la dura suerte

busca perdido el hombre doloroso

la voz que fue su voz. Lo milagroso

no sería más raro que la muerte.

Lo acosarón interminablemente

los recuerdos sagrados y triviales

que son nuestro destino, esas mortales

memorias vastas como un continente.

Dios o Tal Vez o Nadie, yo le pido

su inagotable imagen, no el olvido.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

____________________________

Evelyn Hooven graduated from Mount Holyoke College and received her M.A. from Yale University, where she also studied at The Yale School of Drama. A member of the Dramatists’ Guild, she has had presentations of her verse dramas at several theatrical venues, including The Maxwell Anderson Playwrights Series in Greenwich, CT (after a state-wide competition) and The Poet’s Theatre in Cambridge, MA (result of a national competition). Her poems and translations from the French have appeared in ART TIMES, Chelsea, The Literary Review, THE SHOp: A Magazine of Poetry (in Ireland), The Tribeca Poetry Review, Vallum (in Montreal), and other journals, and her literary criticism in Oxford University’s Essays in Criticism.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast