by Ankur Betageri (May 2018)

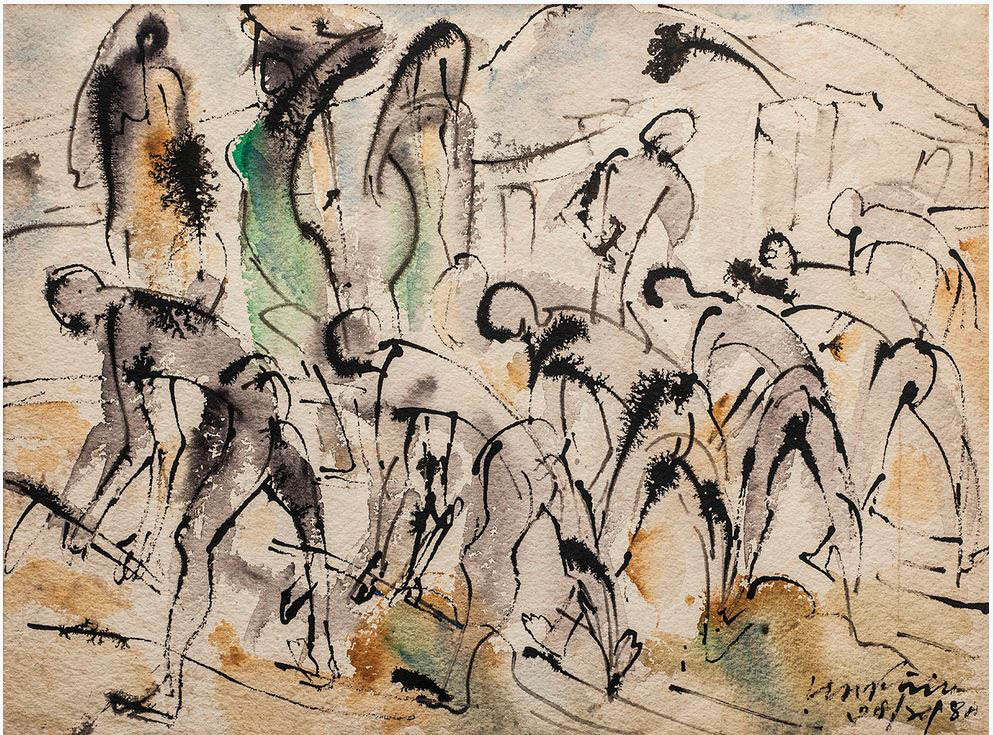

Untitled, Ramkinkar Baij, 1948

The Brown Colonizer

They are foreign to the nation first because of their origin, since they do not owe their powers to the People; and secondly because of their aim, since this consists in defending not the general interest, but the private one.

—Abbé Sieyès, What is the Third Estate?

.jpg) n print the colonizer is always white.

n print the colonizer is always white.

When he struts the streets, stunning everyone

into silence, the brown colonizer is without a name.

Whites and Muslims are marauders, he says.

The British Raj was a ghastly age.

A continual textual rain about its injuries

creates lightning flashes of white man’s menace.

And behind this immaculate screen of whiteness

the brown vampire’s silhouette can be seen

sucking off, quietly, the blood of innocents.

When the attacker becomes the postcolonial victim

the real victim becomes invisible

and the attacker unrecognizable

and thus is the brown empire sustained.

You can tell a brown colonizer by what he says:

He always asks you to take off the ‘western eyeglass’

science and reason, he says, are imperialist tools

the Gita, for him, is the path to liberation

and modernity, he croaks, is a western degeneration

but if reality is also for him an illusion-web

be sure you are dealing with the empire’s very head.

Just smile and smile and get away as quickly as you can

sharpen your knife, wait for the opportune moment.

The Postcolonial Diva Speaks

It is we, the English-knowing men, that have enslaved India. The curse of the nation will rest not upon the English but upon us.

—M.K. Gandhi, Hind-Swaraj

.jpg) plug my ears & scream in their faces:

plug my ears & scream in their faces:

Can the subaltern speak?

Who has the right to speech?

Who has the gift of speech?

Who can with speech mutilate life & decree orders of silence?

The subaltern cannot speak.

Don’t speak to her—you are white

Don’t speak to her—you are black

Don’t speak to her—you are a man

I will speak for her

lean in your microphones, turn your cameras

bring them close to my face, capture my feminine grace

admire my handloom saree, my handicrafts necklace—

Why aren’t you clapping? Didn’t you notice? —I quoted Hegel

in German—corrected a mistranslation of Marx?

And my translation of Derri-da—eta asadhoron na?

Did you get all the allusions in my essay? Of course, I am not defending sati!

What? You read it ten times but couldn’t figure out

“what I am trying to say”? For one thing: I write to play

not to “say” anything—everything there’s to say

has been “said” by Said, I am here to pro-ble-ma-tize—

The speaking for, the power one arrogates to oneself

& the power that one must have to do that—

how no one does that adequately—other than me—

& it isn’t merely because of my skin-tone—You see

caste & race are completely different—But, nevermind—

What is important is that we continue the debates of

the Learned Brahmanas in the new environment &

carry their legacy forward—not cut ourselves off

from that past because of colonial destruction

but the point is subtle—it is not a vulgar binary b/w the oppressor & the oppressed

but the power differential b/w the speaker & the spoken-of

and she is speechless because she is powerless

and because she is powerless she is spoken for, and if she manages to

speak—which she can’t, as I told you—but if she somehow manages to speak

and is heard—then we were wrong about her all the while, she is not a subaltern

coz subalterns don’t have agency by definition, if she is to be subaltern

she must not speak—

The subaltern cannot speak—the discursive structure

I have created will ensure that now, and if she does

it will be called reverse ethnographic nonsense

it will not enter discourse, unless of course

I hear her thoughts and speak for her,

You see, the subaltern

is silence embodied, and my speech is her mind unbodied

and—understand this well—just because I speak does not mean she is

do not presume presence, often it’s from absence

that my speech conjures her image. In short,

it’s all a play of signifiers—there is no one but me

& the text, and nothing is outside the text.

__________________

Ankur Betageri is a poet, short fiction writer and visual artist based in New Delhi. He is the author of The Bliss and Madness of Being Human (poetry, 2013) and Bhog and Other Stories (short fiction, 2010). He teaches English at Bharati College, University of Delhi. His poetry has appeared in Maple Tree Literary Supplement, Mascara Literary Review and London Review of Books..

More by Ankur Betageri here.

Please support New English Review.

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link