by James Stevens Curl (June 2022)

Belfast Landscape: St Anne’s from River House, Colin Davidson

A shortened version of this article was originally published in The Critic xxvii (May 2022) 54-7.

The growth of Belfast during the 19th century was phenomenal: in 1801 the town contained around 20,000 inhabitants, but by 1901, by which time it had achieved city status, it had around 349,000. The Georgian town benefited greatly from the trade in linen rather than its manufacture (which came later), and the influence of those interested in learning and literature was much stronger than would be the case in the following century, earning the place the accolade of ‘Athens of the North’. Cultural life was strongly influenced by the close links with Scotland, for young men from Ulster were obliged to study at Scots universities, notably Edinburgh and Glasgow, because Oxford and Cambridge were closed to non-Anglicans. Belfast had printing-presses in the 1690s, and a newspaper, the Belfast News-Letter, was established in 1737. In 1788 the Belfast Society for Promoting Knowledge founded a library, which morphed into the Linen Hall Library, still in existence today. After the Union of Ireland with Great Britain following the Act of 1800, and the end of the French Wars, Belfast’s port was improved, and shipbuilding began to assume a position of great importance. Foundries, banks, educational establishments, a museum, a chamber of commerce, and much else were set up. Soon, the town was to be called Linenopolis on account of its great number of linen-mills and warehouses, and by the 1880s it was the chief manufacturing and trading centre for linen in the world. Shipbuilding expanded enormously (notably the great yards of Harland & Wolff), as did marine engineering, machine-making, rope manufacture, distilling, tobacco-works, and many associated industries, so by the end of the Victorian age the then city was well-endowed with fine public buildings, banks, public-houses, churches, hospitals, schools, banks, and large mansions for the prosperous classes, nothing of which was suggested in the appallingly biased images of the city portrayed in the media from the late-1960s onwards. There were also a great many small terrace-houses for the working classes, and a fine new cemetery, brilliantly landscaped, with winding paths and numerous splendid monuments to prosperous local families.

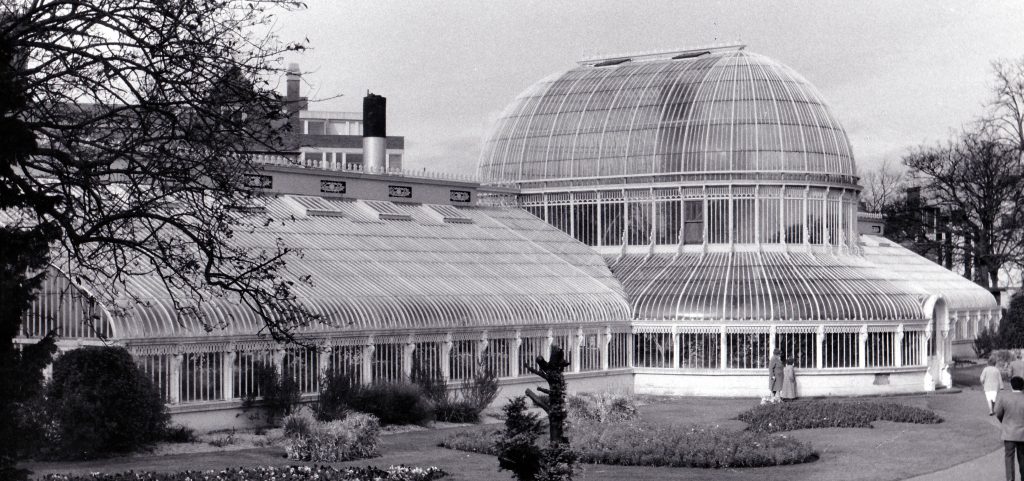

Now impressive buildings need not only money, prosperity, and building skills to be made possible, but architects to design them, and several gifted men rose to the occasion with considerable success. One of the first was English-born Charles Lanyon (1813-89), who designed the Crumlin Road Gaol (1841-4—influenced by Pentonville in London) and the noble Italianate Court House (1848-50—now derelict) opposite. His Palm House, Botanic Gardens, Belfast (1839-40 and 1852) (see Figure 1), is an early and elegant example of curvilinear iron-and glass construction, built with Richard Turner (c.1798-1881) of Dublin, predating Turner’s London collaborations with Decimus Burton (1800-81) at Regent’s Park and Kew Gardens. Lanyon was the architect for the Tudor Gothic Queen’s College (1846-9—now the Lanyon Building of The Queen’s University of Belfast). In 1854 Lanyon took his pupil, William Henry Lynn (1829-1915), into partnership: the firm was responsible for such splendid buildings as the very grand Italian palazzo that is the Custom House (1854-7) (Figure 2), and Lynn was the architect of several distinguished works of architecture both as a partner in the firm and later on his own account.

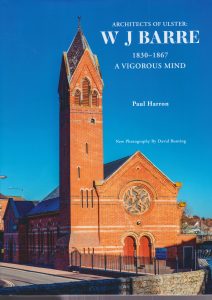

But there was another, whose work is now celebrated in W.J. Barre 1830-1867: A Vigorous Mind by Paul Harron (Figure 3), published (2021) by the excellent Ulster Architectural Heritage Society (and beautifully printed by the old-established firm of W.&G. Baird of Antrim) as part of the series Architects of Ulster. Barre was one of the most prolific of Ulster architects, and certainly left his mark on the Province, and especially on Belfast, having been responsible for several splendid buildings. These include The Ulster Hall, which he won in competition in 1859, at a time when Belfast was being described as ‘the commercial metropolis of Ireland … appropriately as at once the Liverpool and Manchester of this portion of the United Kingdom.’ The Hall (Figure 4) was opened in 1862, and remained Belfast’s principal musical venue (its fine acoustic makes it admirable for concerts by the acclaimed Ulster Orchestra). Among other important works by Barre in Belfast are the former Methodist Church, University Road (1863-5), a polychrome Lombardic-Romanesque brick job with an Italianate campanile featuring spectacular machicolations (Figure 5); the Albert Memorial Clock (1865-9), a Gothic design embellished with a statue of the Prince (d.1861) by Samuel Ferris Lynn (1834-76), brother of W.H. Lynn (Figure 6); and the robustly detailed polychrome Italian palazzo of the former linen warehouse (now Bryson House), Bedford Street (1865) (Figure 7).

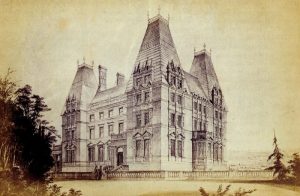

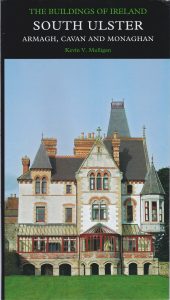

Barre’s grandest mansion was Clanwilliam (now Danesfort) House, erected for the magnate, Samuel Barbour (1830-78), whose linen-thread manufactory was the largest in the world. Danesfort is now the US Consulate, and there is no doubt it is a real showstopper: Mark Bence-Jones (1930-2010) called it ‘one of the finest High-Victorian mansions in Ireland’ (though I query this terminology as it poses the question as to what might be ‘Low-Victorian’), and it is a thumpingly over-emphasised corker of a house, with vigorously-carved details, pierced parapets, and no bashfulness in its eclectic invention (Figure 8). What a shame Barre’s Frenchified Roxborough Castle (from 1865), outside Moy, County Tyrone, designed for James Molyneux Caulfeild (1820-92), 3rd Earl of Charlemont from 1863, was destroyed in 1922 (Figure 9), like so many Irish houses of the landed gentry and aristocracy! Harron suggests that a very fine house, Bessmount, Tyholland, County Monaghan, might be by Barre, even though it was built in 1868: certainly the polychrome brickwork is handled with great assurance, as is the massing of the various disparate elements, and indeed the whole building is of very high quality. Especially delightful is the naturalistic carving of capitals, etc., featuring gluttonous herons, bullrushes, a pike, frogs, a trtout, water-hens, squirrels, a spreadeagled bat, an owl, oak-leaves, and a curiously out-of-place monkey. Kevin V. Mulligan, though, in South Ulster (2013) in The Buildings of Ireland Series, proposes that John McCurdy (1824-85) might be a strong possibility as architect (Figure 9a).

Barre was responsible for several churches, houses, commercial buildings, and other building-types, but he also designed some memorials, including the very peculiar concoction (1861-2) to Captain Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier (1796-1848), who perished in the ill-fated expedition commanded by Sir John Franklin (1786-1847) to the Arctic to find the North-West Passage. Crozier was a native of Banbridge, County Down, and it is in that town where his memorial stands today, a Gothic confection topped with a statue of the intrepid officer. Also featured are carvings showing the ships Erebus and Terror stuck in the ice, scallop-shells, anchors, an Arctic otter with a salmon in its mouth, and a convolvulus to emphasise Crozier’s scientific interests. Four flying buttresses support the central octagonal structure carrying the statue: on those buttresses are what are supposed to be polar bears, but the sculptor, Dublin-based Joseph Robinson Kirk (1821-94), seems to have had an imperfect understanding of what such creatures actually looked like, for they resemble the improbable offspring of shaggy overgrown ferrets crossed with unattractive dogs, and furthermore they ludicrously present their rear ends to Captain Crozier high above them, in poses which have reduced me to helpless laughter every time I have paused to inspect the monument (Figure 10). Barre was on much surer ground with his handsome obelisk (completed 1857) in Monaghan town in memory of Lieutenant-Colonel the Honourable Thomas Vesey Dawson (1819-54), of the Coldstream Guards, who fell at the Battle of Inkerman in the Crimean War (Figure 11).

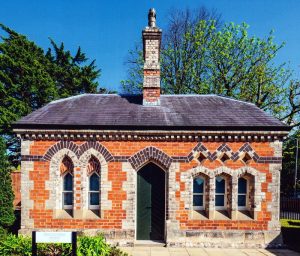

Barre was a versatile designer, who worked in several styles. His Classical work is convincing, as in the handsome Methodist Church in Darling Street, Enniskillen, County Fermanagh (1863-5), with its noble Roman Corinthian pedimented front (Figure 12): its galleried interior is a smaller and less ornate version of the Ulster Hall in Belfast. But if his grander, more showy buildings were often highly competent works of architecture, so were his exquisite miniatures, of which the most perfect is the former gatelodge to Belmont Presbyterian Church, Belfast, with its beautiful polychrome brickwork (red, yellow, and blue-black) and central chimney (Figure 13).

Harron has done the short-lived Barre justice in this well-researched volume, with many fine photographs taken specially for it by David Bunting, and the book is remarkably good value for money, given its quality.

His His admirable and very handsome book* celebrates one of the most important architects who made a massive contribution to the built fabric of Victorian Ulster.

*Paul Harron: W.J. Barre 1830-1867: A Vigorous Mind (Belfast: Ulster Architectural Heritage Society, 2021), ISBN: 978-0-900457-84-5, £28.

**Figures 3-13 are from Harron’s book.

Professor James Stevens Curl, a Member of the Royal Irish Academy, was awarded The President’s Medal of the British Academy in 2017 for ‘outstanding service to the cause of the humanities’ in recognition of his ‘contribution to the wider study of the History of Architecture.’ He has published much on the architecture of Ulster over the years. His latest tome, entitled English Victorian Churches: Architecture, Faith, & Revival, is to be published in London by John Hudson in the Fall of 2022.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

2 Responses

I found this totally fascinating.

Architecture is not really my thing (the only writings on architecture I ever read were accidental pieces by a Soviet writer, Viktor Nekrasov who happened to be an architect by professional training — but I’d read anything by him!) — but this piece opened my eyes on what should have been obvious to me all along — we see most building only from the outside since we walk into very few ones, so insofar as the mass of people is concerned, only the exterior matters. I was always surprised that people talk about external embellishments and forms where seemingly, only the floor plans matter, and how well they fit the stated purpose of the building. But, in 99.99% of cases this is a wrong perspective. I don’t know why I did not realize it before, but it came across loud and clear when I read this. So, many thanks for making me think!