Viewpoints

by Armando Simón (June 2021)

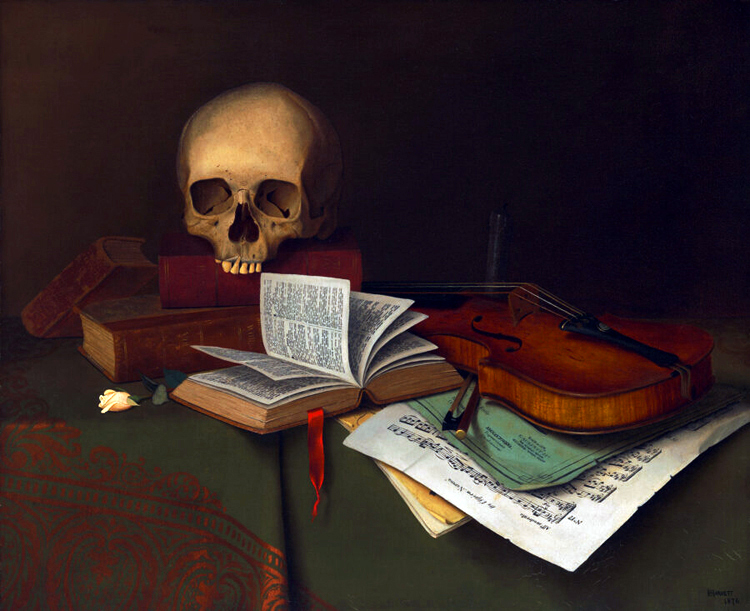

Mortality and Immortality, William Michael Harnett, 1876

Attendance was light, but steady, at the art museum that day. It was good weather outside, which prompted people to go outdoors and some chose the art museum.

One of the visitors to the museum was a young man in his early twenties, idealistic, with his whole life ahead of him. At this moment, he was staring at his favorite painting in rapt admiration. He would look at it, observing the details, take a rest and walk over to look at other paintings or sculpture in other rooms and then come back to worship. He had done this, sporadically visiting the museum, for he was no painter, no artist. He did not study the brush strokes of the canvases and he could not tell you why painting A was superior to painting B, and he could barely distinguish some of the schools of painting and only if they were outstandingly obvious.

As absurd as it may sound, his introduction to art had come through a newspaper article of an interview with the actor Vincent Price, who, aside from being an art collector and connoisseur, was that rarest of Hollywood actor, namely, a good and decent man, and even more unusual, an intelligent one at that, who had praised the Wichita Art Museum as one of the most underrated art museums in the country when he had visited the city. Having read the article, the young man decided to visit the museum, out of sheer curiosity, which he had never done before, figuring there must be something to it to gain such praise (that it reinforced Wichitans’ feelings that their city was highly underrated, if not unknown, by the rest of the country, was not a conscious thought on his part).

Now, whenever you come across a masterpiece—a true masterpiece— you instantly know it. You just know it! The work leaps out at you like a crouching tiger and it just seizes you. You are mesmerized, entranced, and you just stand there—awed. And what’s more, you do not have to be told by someone that it is a magnificent work of art—you know it! You know it, even without knowing who the artist was or when it was created. In fact, the artist’s identity is, in a way, unimportant.

You will be walking down a corridor, mildly interested as you look at some paintings or sculpture when, out of the corner of your eye, you see something that arrests your progress.

So, he had gone, strolling along the halls and was frankly unimpressed.

And then, he saw it.

It was a small painting called Mortality and Immortality. It immediately struck a chord within him, not because of the brushstrokes or the technique or the medium, but because of its theme.

The painting showed, in somber tones, a jawless skull amidst a violin, sheet music and heavy tomes. The overall veneer of yellow-brown for the whole painting was deliberately similar to the brittle pages of old, old books and sheet music and, for that matter, that of aged bones or of violins, thereby enhancing the theme. To him, it seemed to speak volumes, that, yes, we may be mortal, we may die, but our works—our great works—live on. Mozart, Galileo, Finlay, Poe, Beethoven, Chopin, Dickens, Cervantes, Kipling, Edison, Jenner, Unamono, they may all be dead and buried, but their works are very much alive and we will remember those persons because of their works. Often, he drew inspiration from it and had come out of the art museum with a springier step, ready to face the world again.

He came back to the room to view the painting.

He liked to look at the minute details. He was certain that the violin must be a Stradivarius, though he had never seen one and would not recognize one if shown to him and that the notes in the sheet music, barely discernible, were from a master, Vivaldi perhaps. Having absorbed the painting, he moved around the room, wondering how the creator of such a painting could then proceed to paint such other paintings which were insipid and uninspiring.

A couple drifted in and paused in front of Mortality and Immortality. The man was speaking to the woman and, at the first words, which had to do with the particular painting, he drifted over to them the better to hear, eager at having found a kindred soul.

“Ah, here it is! This is one of my favorite paintings in this museum. You see how the light has been handled by the artist, and the exquisite detail given to the objects. The overall somber mood adds to the work.”

The young man behind those words nodded in silent agreement as they then stared at it for a full minute before the man proceeded.

“This work speaks to me. It says that no matter what you may try to do to make yourself appear superior, write a book, or play the violin, the end result is going to be the same, death, and you’re just going to end up as food for worms. All else is vanity.” They contemplated it a few seconds longer and then departed.

The young man stood there, motionless, in shock, as if the man who had spoken had slapped him for no reason whatsoever.

He could not believe what he had just heard.

He actually began to get angry at what he had overheard about “his painting.” It was blasphemy! Sacrilege! How could the man be so stupid as to say that? How dare he! And that bimbo that he was with, why didn’t she speak up? And how could such a dismal interpretation be inspiring to anyone? It was completely contrary to what the artist had intended to portray!

He looked at the canvas and wondered how anybody could be so blind as to what was right in front of their eyes, plain as could be.

He felt indignant and, yes, even personally insulted, though he could not then have told you exactly why. He peered at it to see if the man’s version was anywhere on the canvas, hidden, and finally relaxed, assured that it was not there, yet still feeling incensed.

A new determination seized him. By God, he’d straighten him out! He’d show him what’s what! Politely, but firmly.

He strode out of the hall in search of the couple, proceeding down one hall and looking into rooms, but they were not there, so he retraced his steps and went the opposite way but by then he was too late and they had already left.

__________________________________

Armando Simón is a retired psychologist who has published several fiction books and stage plays.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast