Waiting for the Son

by Armando Simón (November 2023)

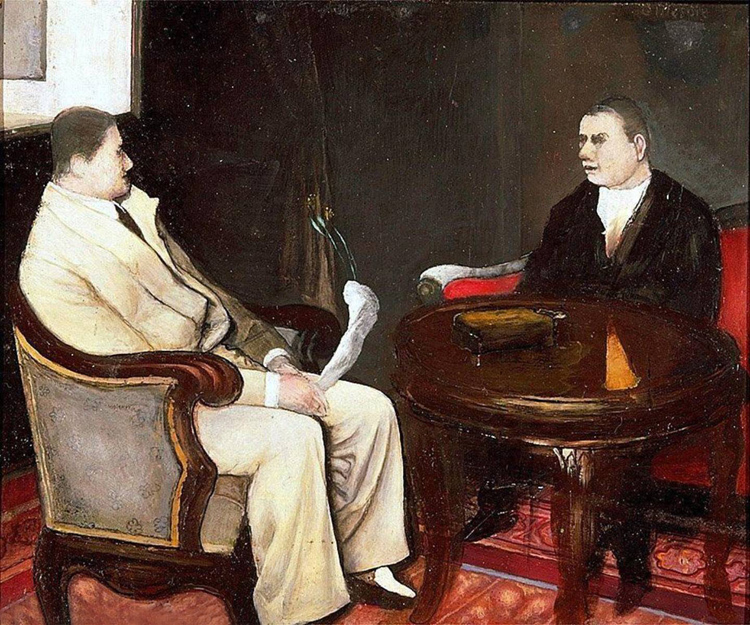

Two Men Seated, Gregory Gillespie, 1962

Mister Pertinax hung up the telephone after having left a third message that day on his son’s voicemail. The way he was feeling he wanted to scream, to plead, to chastise. Instead, he had made an effort to keep his voice on a level tone, asking him to call back, knowing instinctively that if he spoke to him in any of the above tones his son would be annoyed and would further avoid him.

Mister Pertinax had a real hunger to see his son. That was the word, hunger. If too many days passed without him seeing his son, or worse, not hearing his voice, he became increasingly unsettled the more the number of days passed until (he acknowledged this to himself) he became irrational, alternating between worry for Charly’s well-being, or anger and bitterness over his son’s unfilial attitude towards his father. In short, even though his only son was in his early twenties, Mister Pertinax still loved his son, madly so, as if he were still five. Or ten. Or eighteen. He was one of those fathers whose sun rises and sets around his son (yet, contrary to what one would have expected, Charly had purposively not been spoiled). Mister Pertinax found it incomprehensible how some of his masculine acquaintances were uninterested in their own adult children.

Charly was presently going to the university to get his degree in chemistry while holding down a part-time job. His father was helping him financially. He had moved out of his parents’ home at age twenty, silencing their objections—his father’s strong objections—with the one argument that would stop his father dead in his tracks.

“Dad, I want to have a place where I can bring my girlfriends to,” he had said.

What could you say to that?

At the same time that he felt bad that Charly had demolished his arguments, he also felt a paternal and masculine pride in his son at the prospect of his future conquests.

“I guess the back seat of your car has pretty much worn out,” his father had finally responded.

There was one other factor that neither of them was conscious of. It was the concept that, in America, it is considered shameful for a son to continue living with his parents, particularly his mother, past an (indeterminate) age. This contrasts with families in Italy, Spain, Japan, China and Latin America where it is considered normal and where the sense of family is that much stronger.

Initially, during the first couple of years, Charly and his parents visited each other frequently on an almost daily basis. He would come over for dinner and to do his laundry in his parents’ washing machine. Neither parent thought he was taking advantage of them. To his parents, washing his clothes was not a chore, it was a pleasure.

Lately, though, he had become more distant. He spent most of his free time with his friends and his girlfriends. Mister Pertinax knew this to be a natural stage of life. He understood it. Nevertheless, his son’s absence pained him, and the pain increased as the intervals between visits got longer and longer.

Mister Pertinax could appreciate the irony. He was reliving the very same scenario that had transpired with his own father, decades ago, when the old man would look at him with such longing as his visits grew less and less frequent. The more that his old man had clutched at him the more exasperated he felt and wanted to escape while, paradoxically, wanting to stay and spend time with him. Worse, the father-son aphasia that was present when they did spend time together did not help one bit. These days, Mister Pertinax was trying hard not to sound like his old man. He did not want to drive Charly away.

The phone rang and it was his son.

“Well, it’s about time,” he tried to joke.

“Sorry, Dad. Been busy.”

“Come on over for supper.”

“Ah, naw, I’m tired. I’ll just make me a sandwich.”

“Forget the sandwich,” his father said, trying to mask the desperation in his voice with a lighthearted tone. “Come over. We haven’t seen you in a while.”

“No, thanks, Dad. I just want to lie down.”

“So lie down here! Charly, your mother hasn’t seen you in days,” he heard himself beg. Saying this, he grabbed his wife and put her on the phone. Whether it was the combination of both parents that wore him out, or Charly being partial to his mother, the boy agreed to come over.

The father was going to give him a tongue lashing when he came over, but his anger disappeared the moment that he set eyes on his son. Mister Pertinax was conscious that he was partial to his son, but he nonetheless thought him a very handsome lad, even with his blonde hair dyed purple, something that Charly had done some days ago, mostly because of a girlfriend whom he was dating.

Charly, predictably, brought over his dirty laundry, which he began to wash. Ordinarily, his mother would take care of it, but she was busy in the kitchen, preparing one of her son’s favorite dishes and he wanted to take the clothes back with him.

“So, what’s new?” Mister Pertinax asked him. Charly told him a few things going on in his life but was sparse with the details. The father recognized the symptoms of early father-son aphasia. Trying to get information out of him was like pulling teeth, his father thought. The son steered the conversation onto less personal, more abstract topics and, hence, safer ones. Politics. The news. Sports. Movies. Even so, a closeness was felt by both in discussing these subjects, something that would probably not have been the case between females when discussing these impersonal matters.

“My new girlfriend’s into British comedy,” he finally volunteered something personal. “She’ll be laughing over something on the ‘telly’ and I’ll just be sitting there scratching my head, trying to figure out what’s so funny.” After this, the personal comments disappeared.

No matter. To his father, any conversation with his son was better than none at all. Unfortunately, before too long. Charly wanted to watch a show on television, so even that conversation dried up. No matter. To his father, his son being physically present was better than no presence at all.

Dinner was pleasant enough. Charly’s appetite had not diminished one bit and he cleaned out his plate.

“I made extra for you to take to your apartment,” his mother said. “It’s in the blue Tupperware container, by the stove.”

“Great. Thanks, Mom.”

“Charly. The symphony’s having an all-Beethoven program. I’m going to go. You wanna come?” Actually, he was not going to go unless his son accompanied him. He had asked casually, eliminating any sound of eagerness in his voice.

“Beethoven? Oh, yeah! Great! When?” Beethoven was both their favorite composer.

“How about tomorrow night? Otherwise, it’ll be on the weekend and I know that you want to keep your weekends free for your girlfriends.”

“Yeah, tomorrow’s good. What time?”

“Eight. Come over at six tomorrow for supper and we’ll leave from here. OK?”

“OK.”

Mrs. Pertinax was not interested in classical music one bit, so he would have his son all to himself. His father chuckled at imagining his son with his purple-dyed hair sitting in the symphony audience.

Eventually, Charly headed on back to his apartment, taking his washed and dried clothes as well as the food in the Tupperware. After he left, the parents talked about the pleasant visit. His mother thought that he looked thin and probably was not eating well or regularly.

That night, feeling very, very happy, Charly’s father went to bed with the contented knowledge that he would see his son two days in a row. On about two in the morning, he passed away in his sleep.

Table of Contents

Armando Simón is the author of This That and the Other.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast