What We Do

by Theodore Dalrymple (March 2021)

Cricket (from British Sports and Games), circa 1880

As a child I went, or was taken, several times to London Zoo. In those days, the fact that lions and tigers spent their lives pacing up and down in their cages did not strike us as odd or wrong, but rather as natural: that was just how lions and tigers behaved, presumably in the wild as well as when caged. Circuses in those days also trained lions to jump through burning hoops and elephants, holding each other’s tails by their trunks, to form revolving circles. Achondroplastic dwarfs ran dementedly round the circus ring to the great amusement of the audience, though this caused me, in contrast to the way animals were treated which I accepted without demur, some inchoate uneasiness.

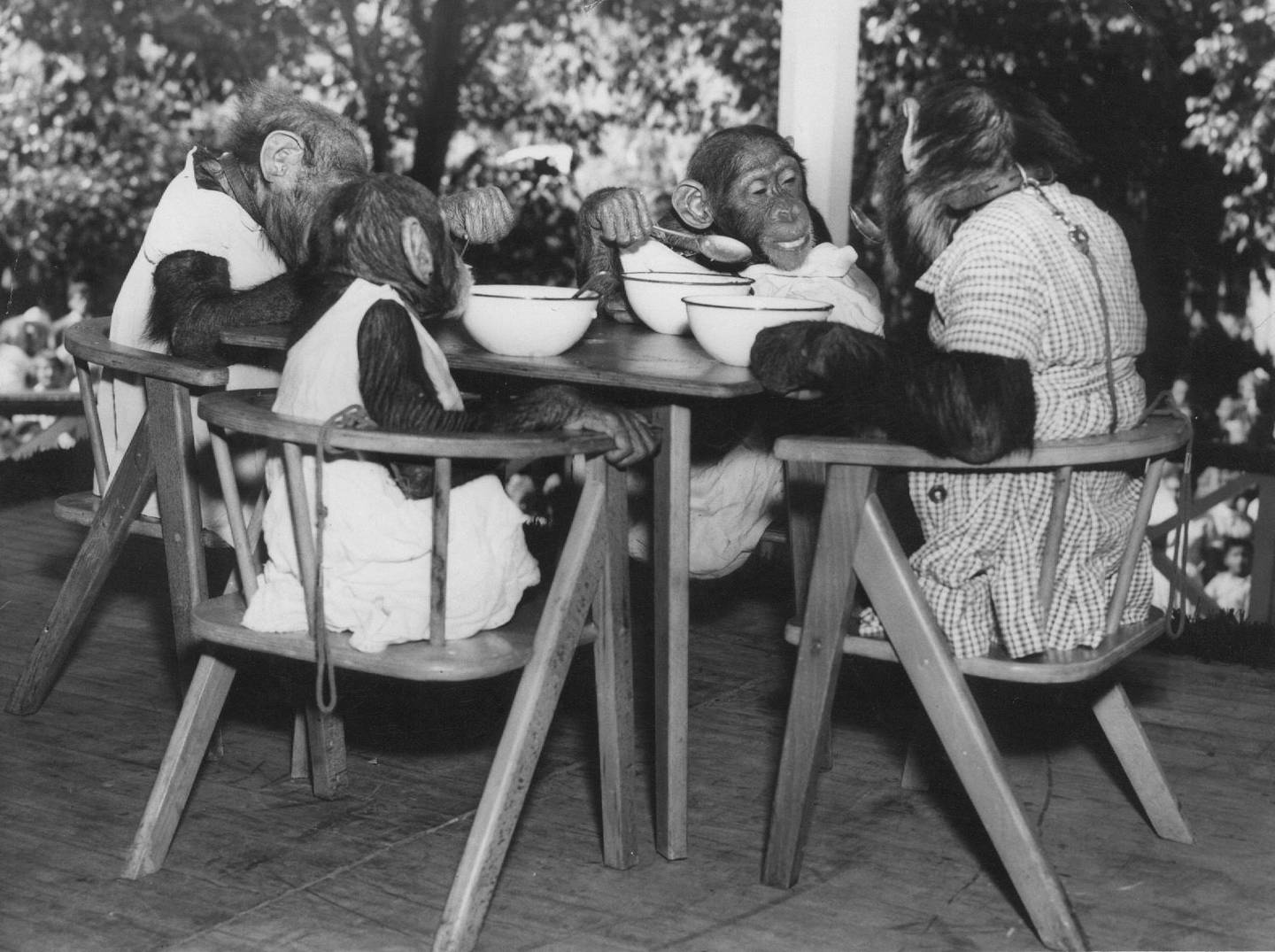

In those days, the hippopotamus house, which smelled awful, had a notice saying Please excuse the smell, but we like it. I haven’t been to the zoo for a long time, but I doubt that this kind of facetiousness would be permitted any longer. And in those days also, one of the chief attractions was the chimpanzees’ tea party, that took place daily (if I remember correctly) at four o’clock every afternoon. Chimpanzees were dressed up in ridiculous costumes, including flowered dresses for the females, and trained to sit around a table, pouring tea, eating cake and so forth. Everyone found this hilarious, but now we should find it appalling. Sensibilities change, sometimes for the better, though in the process of betterment we become, perhaps, more solemn. Did the chimpanzees really suffer from being exhibited and laughed at in this fashion? I don’t know: but we have since adopted a deontological principle that animals do not exist, and should not be exhibited, only for our amusement, but have an inherent dignity which ought to be respected. I am not sure this applies to wasps or termites or fleas, or many other creatures which I could name, but nevertheless I think as a general principle, albeit with or exceptions, it is not a bad one.

Curiously enough, I felt that the penguins were more human, and also amusing, than the chimpanzees and therefore I had more sympathy for them when their keeper, who wore a uniform with peaked cap, fed them with small fish from his bucket. I thought that he was trying to get a cheap laugh from them, though of course the way they dived into the water after the fish was a good deal closer to nature than the chimpanzees’ tea party.

Whenever I was taken to the zoo, I expressed a wish to go to the reptile and the insect houses, but this was regarded by my accompanying adults as aberrant, and it was only because of my persistence that I was allowed a brief excursion at the very end of our visit. I was left to walk through them quickly, with strict instructions not to linger. No one else wanted to view these errors of nature.

I remember in particular the giant African millipedes, Archispirostreptus gigas. They were indeed disgusting from the aesthetic point of view. They could be a foot long and their legs (two a segment) moved in waves. Their progress across the ground had something insidious about it, something that sent shivers down my spine, something appalling but also fascinating. I don’t think that I could have picked one up or let it run over me for the sake of any reward whatever.

Even worse, but also horribly fascinating, was that they had tiny white mites running over their jet-black surface. Why did not the zoo keepers clean them up, I wondered? Because of their black shiny surface, it would have been easy enough to wipe them down. I had no conception at that age of symbiosis, that the mites derived their sustenance from cleaning up the outer surface of the millipedes to the latter’s benefit; I merely projected on to the millipede what I would have felt if I had had white mites running all over me. I was appalled, disgusted, riveted.

My visits to the insect house probably immunised for ever me against the uncritical worship of Nature. Not all the phenomena of Nature are beautiful, certainly not at first appearance, though they may be remarkable, if not to those who intimately familiar with them or who grow up with them. I suppose that those who have been acquainted with the giant millipedes since childhood, who live in or near their natural habitat, see nothing remarkable in them: it is unfamiliarity that breeds initial amazement. (Deeper amazement is another thing: there is nothing more remarkable about a giant millipede than there is nothing more remarkable about a giant millipede than there is about a housefly, whose existence we take for granted because we encountered houseflies soon after we were born and have never been completely without them. Education should, at least in part, be the installation of amazement and the undermining of taken-for-grantedness.)

Millipedes are disgusting—at least to me—but centipedes are frightening, vicious little creatures. How have I come to this judgment? Is it the result of some information absorbed early in life—for example, that centipedes can inflict a painful bites while the worst that millipedes can do is secrete unpleasant chemicals when under attack—or is it because of the inherent appearance of the creatures themselves? Millipedes look herbivore, more brontosaurid than tyrannosaurid, while centipedes look more tyrannosaurid than brontosaurid.

I was surprised, however, to learn recently that millipedes are not entirely harmless. In Japan there is are species known as train millipedes because, when they swarm in enormous numbers, which they do every eight years, they can hold up trains. In Britain, we are used to delays to trains because of leaves on the track, or rain or snow (said to be of the wring type), suicides or drunks, but not because of an invasion of millipedes. I have been unable to find out whether the millipedes hold up trains because they threaten to derail them, or because of the solicitude for their welfare by the railway company. Maybe it is the fact that, when attacked, these particular millipedes emit cyanide, very little individually of course, but presumably a significant quantity if tens of thousands of them are attacked at the same time.

The fact that they have cyanide secreting glands protects them from being preyed upon when they swarm. Other swarming creatures such as certain types of cicadas are preyed upon when they swarm, but not train millipedes.

I should think it is very frustrating to have one’s train postponed or cancelled because of millipedes on the track. I can just imagine the reaction of the passengers when they hear the passenger announcement in the station: what will they come up with next as a fatuous excuse? I suppose a few of them must be intrigued, however, and want to see the millipedes for themselves. Certainly, when I have been in an underground train held up when someone has thrown himself in front of the train, I have noticed that humanity divides into two: those who strain to look and see what has happened, and those who grumble at their luck that it had to be their train that the suicide chose to jump in front of.

Swarming caterpillars, known as the African army worm, once had a minor effect on my life. I was playing a game of cricket between English expatriates on a rough and ready pitch in East Africa when the game had to be abandoned by the approach of a vast column of African army worm. These caterpillars devour everything in their path, and will not deviate from that path, however it has been decided upon. Numbers are on their side: it is as if they are led by some lepidopteran Mao Tse-Tung, who wouldn’t mind the loss of half the population so long as the end is achieved. We, representatives of the highest product of evolution, were forced to cede to a marching column of mere insect pupae.

My cricketing career has been an odd and inglorious one, at least in the sense that I never managed to perform any sporting feats. I did once, however, play at the Oval, a huge stadium in London, with a crowd capacity of tens of thousands, though no one came to watch me—or my fellows. I was part of a team representing the Spectator that was playing a team representing the Coach and Horses, a pub in London’s Soho patronised by journalists and other deplorables, including (in his time) the great poet of undoubted genius, Dylan Thomas.

Of the patrons, the most deplorable or notorious was a man called Jeffrey Bernard, who actually umpired the cricket match, at least for a time. He could be relied upon to be neutral because he wrote for the Spectator but drank (and how!) at the Coach and Horses. Indeed, his drinking, and the problems it occasioned, was the subject of his weekly column called Low Life which sometimes failed to appear, it absence that week being explained to disappointed readers by the lapidary statement that ‘Jeffrey Bernard is unwell.’

His column was once described as ‘a long suicide note’ and he did indeed die at what now seems to me the comparatively early age of sixty-five, of the natural consequences of smoking sixty cigarettes a day and taking vodka for breakfast, as well as for luncheon, dinner and tea. He had that way of insinuating, as many old roués do, that anyone who thought that his way of life was, perhaps, less than wholly admirable, was an unsophisticated and censorious prig. But he managed, at least, to turn his proudly dissolute existence into literary form.

Cricket is a long game and, especially in hot weather, as it was on this occasion, refreshments must be taken during it. Refreshments were particularly needed by Jeffrey Bernard, and were brought to him constantly while he was umpiring. They consisted of gins and tonic and before long he had had so many of them that first he swayed and then he passed out and had to be carried off the pitch. I thought he had died, though he in fact survived a few more years, albeit after the amputation of one leg. His end was tragic and in a way heroic: dying of kidney failure, he refused the offer of renal dialysis, thus accepting that the continuation of life at all costs could not be the aim of the good life.

Trivial as our game of cricket was, being of not the slightest importance as a contest even in the unimportant realm of sport, I unexpectedly conceived while standing in the middle of this vast stadium, albeit with no greater crowd present than the odd wife or girlfriend, a respect (which I never had before) for the sportsmen who performed professionally in such stadiums in front of thousands of their fellow beings. The vastness and the openness make one feel small and vulnerable even in the absence of a huge crowd—a crowd which might, if present, be wishing you to fail if you are not playing for the home team. On the other hand, if you are playing for that team, you know that the hopes of the crowd are resting on you and that failure in performance will disappoint it bitterly, and that its support or adulation might quickly turn to derision or even hostility. And all the while you have to perform, having honed your skills but not having rehearsed the performance which must remain spontaneous and unrehearsed, at the highest level against people who can never be much below your own level of accomplishment and may well be above it. Your only hope is to lose yourself and so absorb yourself in the match itself that you dissociate yourself entirely from the rest of the universe. I presume that sportsmen must perform almost in a state of dissociation.

It is much easier, really, to be a train millipede or African army worm, to have no ambition, not to try to stand out from the crowd, not to try to achieve excellence in any endeavour whatever, however trivial (such as sport), but to go in the same direction as everyone about you. Happily for us, if not for the world, that is what we mostly do.

__________________________________

The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Kenneth Francis) and Grief and Other Stories from New English Review Press.