What Would Shakespeare Do?

by Theodore Dalrymple (March 2024)

It is a brave man who claims to know what Shakespeare himself thought. Shakespeare was a man of such protean sympathies, such ability to work himself into the minds of others (allowing us to follow him there), that it sometimes seems as if had he could have had no thoughts of his own, like an actor who has played so many parts, and for so long, that he no longer has a fixed personality, any more than a chameleon has a fixed colour.

Still, I think we can advance some negatives about what Shakespeare thought. No puritan could have written Measure for Measure, for example. I think it safe to say that Shakespeare did not like mobs. I doubt that he would have been impressed by any theory of human conduct that claimed to explain all of it by a single principle. It follows from this that he would never have believed in a categorical imperative that could guide men to moral conduct in all situations.

Shakespeare’s religious beliefs have long been a matter of speculation (as has everything else about him). Some have claimed him as a closet Catholic. His father, after all, was, or had been, a Catholic, and multisecular beliefs, customs and ceremonies are not to be laid aside like a cloak. But one of the great pleasures of Shakespearean speculation is that no conclusion is ever definitive. The heat between disputants may rise, but nothing catches fire as a result.

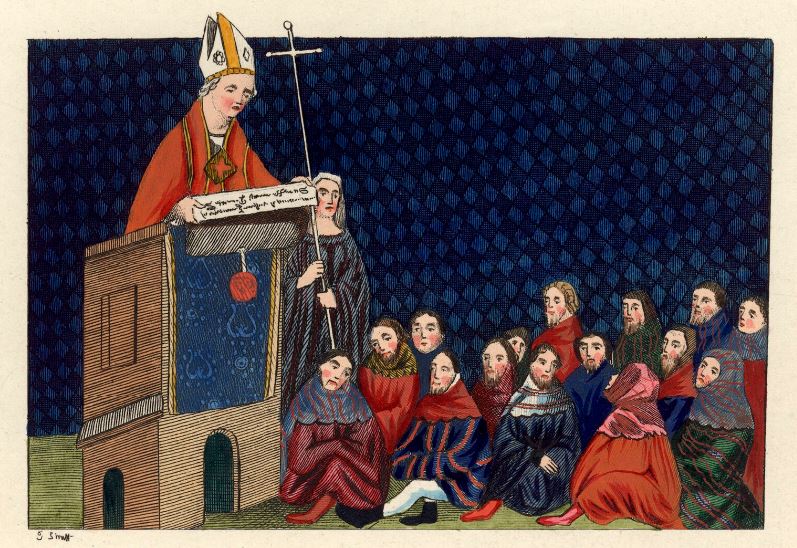

Henry V is not complimentary about organised religion. The opening scene, after the Chorus that invites us to suspend our disbelief in the verisimilitude of what is to follow, is between the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Ely (at the time of the action, both Catholic prelates, as the audience would have understood). There is not much spiritual about them; of the world, they are worldly.

The Archbishop is deeply concerned by a bill before Parliament, first put forward in Henry IV’s day but not promulgated because of the civil disturbances with which that monarch had first to deal, to confiscate the better half of the Church’s lands, and therefore its income. This confiscation would be much to the secular power’s advantage; in Holinshed, the proposed act was justified by the clergy’s alleged mismanagement of the lands and income, and by the assumption that they would be much better used by the secular power (a justification of expropriation ever since). The Archbishop and the Bishop are most anxious to head off the bill that, says the Bishop, ‘would drink deep’: to which the Archbishop adds that it would ‘drink the cup and all.’

When the Bishop asks the Archbishop ‘How, my lord, may we resist it [the passage of the bill] now?’ the Archbishop replies, ‘It must be thought on.’ At no time, however, does he resort to the kind of utilitarian arguments that one might expect, at least today for example, that society as a whole will suffer from the confiscation if it were to be carried out, that it is the religious who keep learning alive, who educate youth, who provide medical care for the poor, and so forth. He does not attempt to refute the allegations of mismanagement, corruption, luxurious living, etc. The question is for him is a purely practical one, that of preservation of the Church’s material interests.

The Bishop alludes to Henry’s profound change of character on his ascent to the throne, and how he has since become pious, ‘a true lover of the holy Church.’ The Archbishop somewhat sententiously praises the king:

Hear him but reason in divinity

And all-admiring, with an inward wish

You would desire the King were made a prelate.

But if the king is now eager to dress his policy in the tissue of principle, he is clearly not unsusceptible to material inducements – in essence bribes. When the Bishop asks the Archbishop whether the king supports the bill, the latter replies:

————————He seems indifferent,

Or rather swaying more upon our part

Than cherishing th’exhibitors against us.

The reasons the Archbishop then gives for this inclination towards the Church’s side would have delighted Karl Marx himself, for whom religion was but an ideological cover or disguise for material self-interest.

For I have made an offer to his majesty,

Upon our spiritual convocation,

And in regard to causes now in hand

Which I have opened to his grace at large,

As touching France, to give a greater sum

Than ever at one time the clergy yet

Did to his predecessors part withal.

In other words, the Archbishop encouraged Henry to push his claims in France, inevitably by mean of war, and then offered to help pay him to do so, all in the effort to avert the bill. Into this, we are to assume that he mixed flattery: for would he have forborne to mention then to Henry, as in fact he does later, that he was being given more money by the Church than any of his predecessors had been given?

Knowing that Henry was anxious to justify his policy by moral and legal argument, the Archbishop then rationalises Henry’s claim to the throne of France, without so much as a glance at his dubious claim to the throne upon which he already sits, and having done so, encourages Henry to take up arms:

Stand for your own, unwind your blood flag…

Forage in blood of French nobility.

I am not myself a theologian, but this seems hardly consonant with my no doubt naïve reading of the Gospels.

The Archbishop then repeats the offer of subvention. The nobles should:

With blood and sword and fire to win your right,

In aid whereof we of the spirituality

Will raise your highness such a mighty sum

As never did the clergy at one time

Bring in to any of your ancestors.

The prelate then analogises human and honeybee society, in which different groups in each have different functions. Enumerating the different kinds of bees, the Archbishop says:

Others, like soldiers, armed in their stings,

Make boot upon the summer’s velvet buds,

Which pillage they with merry march bring home

To the tent-royal of their emperor…

The message could hardly be clearer: pillage is justified, indeed almost a duty. The analogy with bees is preposterous and obviously wicked: loot is not pollen and no bee was ever encouraged to gather pollen by means of a comparison with looting soldiers.

This is almost the last word of the Primate of England in the play, in which the Church appears to be about as spiritual an institution as Wall Street. No thought of God makes itself manifest in the Archbishop’s discourse; no prince of Machiavelli could be more solicitous of his own position or power, or ruthlessly determined to preserve it. Let thousands die, so long as the Church’s revenues are healthy.

Whether any playgoer noticed this, as the lines sped by, is another question: but the figure of the Archbishop could hardly have promoted respect for the Church, whether Catholic or Anglican. How far Shakespeare himself subscribed to this deeply subversive quasi-Marxist depiction of organised religion and the upper clergy is also another question; it depends on how far he intended the Archbishop to be regarded as an individual, and how far as emblematic of the Church as a whole: but either way, the Archbishop is as scheming as any usurping king.

Henry believes in God, but also that God believes in him. God is distinctly useful to him. The most famous speech in the play, ends

Follow your spirit, and upon this charge

Cry ‘God for Harry! England and Saint George!’

In the previous thirty-two lines, however, there is not a sentiment that a pagan or a complete non-believer could not have uttered. God is brought in as an auxiliary, not for the first or last time in literary history. What the breach is to English dead of Henry V the corner of some foreign field that is forever England is to Rupert Brooke, who also manages to invoke God, rather weakly, as an auxiliary. His heart is a pulse ‘in the eternal mind’, which bespeaks no very fervent orthodox belief.

When Henry has won his great victory, he attributes it to God:

===========O God, thy arm was here;

And not to us but to thy arm alone

Ascribe we all…

===========Take it God, for it is none but thine.

This is, of course, a common enough conceit in history, that of military victory being ordained by God and hence as a sign of God’s approval (in Marxism, a religion without God, History, with a capital H, plays the part of God). This ought to have the corollary that defeat is also by God’s intervention alone, for the other, victorious side can always, and with equal justice, claim it as God’s. Perhaps only some victories are ascribable to God, then; but if so, how are they to be distinguished from those victories that are not God’s alone? Shakespeare was vastly too intelligent for this puzzle to have escaped his notice, and I doubt that he would himself have attributed the victory at the Battle of Agincourt to divine providence.

At the beginning of the fifth act, the Chorus asks the audience to imagine Henry’s entrance to Blackheath:

Where that his lords desire him to have borne

His bruised helmet and his bended sword

Before him through the city. He forbids it,

Being free from vainest and self-glorious pride,

Giving full trophy, signal and ostent

Quite from himself to God.

This, to me, has all the ring of Richard III’s bogus piety. Richard, in order to appeal to the gullible populace, feigns religious modesty, and when he appears between two clergymen before the crowd, his soon to be betrayed éminence grise, Buckingham, says:

Two props of virtue of a Christian prince,

To stay him from the fall of vanity;

And, see, a book of prayer in his hand.

True ornament to know a holy man…

We feel that Henry is managing his image, like any modern politician.

The only true religious feeling in the play is that of Falstaff, the roguish fat knight, and that of Mistress Quickly. Falstaff does not appear in the play, though many people remember him as having done so, the description of his demise by Mistress Quickly (now Pistol’s wife) being so vivid. The passage is very familiar:

‘How now, Sir John?’ quoth I, ‘what, man! be o’ good cheer.’ So

’a cried out ‘God, God, God!’ three or four times. Now I, to

comfort him, bid him ’should not think of God; I hoped there was

no need to trouble himself with any such thoughts yet.

Clearly, Mistress Quickly tries to comfort Sir John by telling him that he is not dying. Her belief in God is not orthodox, perhaps, for she thinks that one need not think of him until one is close to death, or in the midst of some other crisis, which I doubt that any theologian would concede; but her belief is genuine, more genuine than the King’s because less calculating. Shakespeare does not laugh at her theological naivety; on the contrary, we love her for the simple good heartedness of it. It is beside the point whether God exists or not.

As for Sir John—the old roué, the toper, the fantasist and fabricator of outrageous stories—he turns out to have a genuine belief in God, again much more genuine than the King’s. A man’s testimony on his deathbed used to be the only testimony that could be entered in a court of law without cross-examination, because it was believed that such a man would not lie, having no reason to. When Sir John calls out, ‘God, God, God!’ we do not know whether it is in hope or despair, whether he has seen his life pass before him in an instant, as it is said to do to the dying, and repented of it, or whether he has seen the glory of God.

But Mistress Quickly has, in the charity of her soul, seen Falstaff’s essential innocence, his real lack of malice or evil. She says, to Bardolph’s suggestion that he might have gone to hell:

Nay, sure, he’s not in hell, he’s in Arthur’s bosom (she means

Abraham’s, but again we do not laugh at her ignorance, we love

her for it), if ever a man went to Arthur’s bosom. ’A made a finer

end, and went away an [as if] it had been any christom child.

A christom child was a christened child who died within one month of its birth and was supposed completely innocent. The term also has the connotation of good Christian, so that Mistress Quickly, who knows all about his jackanapery, sees in Falstaff a good man. She is tolerant, generous-minded and forgiving, and comes far nearer to the precepts of the Sermon on the Mount does Henry—who, in fact, is a million miles from them. Ignorant and bawdy as she might be, she is more truly religious than Henry.

Shakespeare doesn’t put all his cards on the table and tell us that any particular religious doctrine is true (and therefore that others must be false). But he does make one kind of religiosity, naïve and instinctive, attractive, while another kind is somewhat repellent, which is to say instrumental, hypocritical and self-interested. He favours common humanity over ambition and the lust for power.

Table of Contents

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest books are Neither Trumpets nor Violins (with Kenneth Francis and Samuel Hux) and Ramses: A Memoir from New English Review Press.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast