Whisper Louder Please

by Samuel Hux (September 2019)

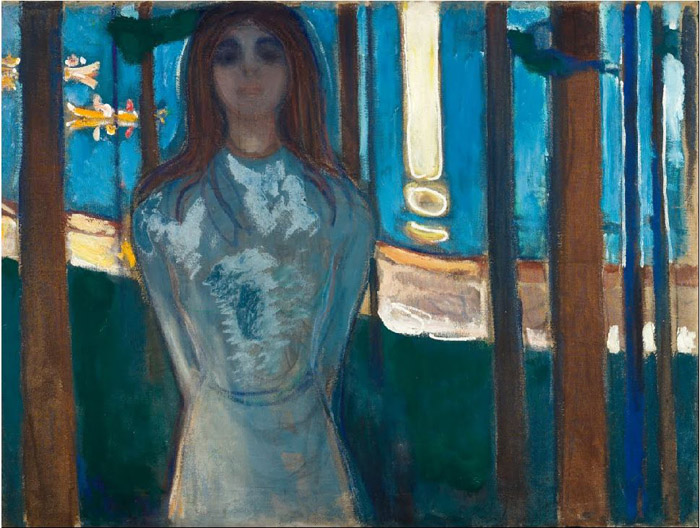

The Voice, Edvard Munch, 1896

Brief digression: not exactly in the theatre, but related to. A few years later, a well-heeled friend and colleague, a theatre historian, who lived in the fabled Hotel Chelsea in lower Manhattan, threw a cocktail party for the cast of Peter Brook’s Royal Shakespeare Company production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, temporarily residing in the Chelsea. I was honored and flattered to be her only faculty colleague to be invited to the bash. I wasn’t totally surprised since I had long sensed an affinity, a distant kinship as it were resting in the fact that we were both Southerners living in the big city, although she black and I white. When I arrived, I discovered that she wanted me to tend bar. “Yes, ma’am,” I yielded. Thus, this minor footnote to theatre history. Now back to Marat/Sade . . .

Or actually The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat As Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of The Marquis de Sade. I saw it twice, as I’ve said, as well as the film of the production countless times. I required its viewing as a slightly off-kilter offering along with classic dramas such as Oedipus Rex, Hamlet, Lear and philosophic classics by Aristotle, Hegel, Nietzsche, and Unamuno in a course called “The Tragic Vision.” I’m inclined to divide the human race into two categories: those who’ve seen Brook’s production and those who haven’t. And I advise you to join, through the miracle of film, the right group.

Read more in New English Review:

• Days and Work (Part 3)

• Jorges Luis Borges: Out of Sync with Argentina’s Other Iconic Figures

• Piped Music in Public Spaces: Pollution Unchecked

Brook was a genius, evinced as well by A Midsummer Night’s Dream and his film of King Lear with Paul Schofield. But back once more to Marat/Sade—which was transcendently excellent not only because of the internal brilliance of Peter Weiss’s play but as well because whether it was Marat (Ian Richardson) declaiming his revolutionary calls or Sade (Patrick Magee) deriding with slight compassion Marat’s delusions or Charlotte Corday (Glenda Jackson) seductively singing of her murderous plans for Marat or any other actor doing his or her roles . . . every single word or verbal gesture rang clear as a bell. Even a mad patient through his insane slobberings: “A mad animal / I’m a mad animal / Prisons don’t help / Chains don’t help / I escape through all the walls / through all the shit and splintered bones / You’ll see it all one day / I’m not through yet / I have plans.” Every single word impossible to miss. Brook, I’m sure, would have agreed with the great Judi Dench, who advises young actors to learn from the recordings of Frank Sinatra, whose every word—no, every syllable—is pronouncedly clear. Kenneth Branagh, when directing, tells his younger actors that if they don’t understand fully their lines simply say them very clearly. I might say this is an English, British theatrical tradition (from which the American theatre unfortunately has learned little) were it not for— but here I get slightly ahead of myself.

Anyway, given the pleasure I had experienced of Peter Brook’s directorial hand, I was looking forward to November, 2018 for Brook’s direction of his own drama at the Yale Rep in New Haven, The Prisoner.

In an unidentified land, a young man has murdered his own father because of his father’s incestuous affair with his daughter, the sister of the young man (who was the young man’s own sexual mistress). As punishment for his patricide, young man is condemned to sit for years and years and years facing a prison—outside the prison, that is—the prison located somewhere to the rear of us the audience, until young man has internalized the prison, at which time he will be released . . . along with the audience, I might add.

I know some of this because afterwards I read the playbill . . . which I normally avoid reading before the play begins, preferring not to be assaulted by some dramaturge’s ramblings. But nothing of this was clear while the play was in progress, because . . .

. . . well, because, you see, the dialogue between the young “prisoner” and various visitors to his “imprisonment” spoke (out of, I expect, respect for his terrible predicament) sotto voce (as one would of course in actual life). So, sotto voce the dialogue and lonely soliloquies were—with the result being that a person with anything close to normal hearing and sitting in good seats, as we were, could not follow a goddamned thing. At one point, my much-better-half, who can hear dropping pins, is graced with exquisite manners, and a dramatist herself respectful of all theatrical proprieties, shocked even me by declaring clearly and audibly “We can’t hear you”—to no avail.

In consequence of all this, Peter Brook, who was present that evening by the way, provided me with one of the most miserable evenings I have ever spent in the theatre. And I don’t feel forgiving because of his age. If one is 94, one should know better than this.

Of course, it’s not only a matter of whispering. More importantly it’s a matter of clarity of speech, instead of the verbal stumbling and word slurring and mumbling that are natural in everyday conversation or out-loud thinking. But professional actors traditionally have known how to convey a pretense—if you will—of verbal imperfection approaching inarticulateness in such a way that the dialogue or monologue is thoroughly comprehendible. Think of Marlon Brando for instance, whether as Stanley Kowalski in Streetcar Named Desire or Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront. Recall Terry in the back seat with his brother (Rod Steiger): the heart-breaking “I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender.” I don’t think John Wayne, naturalistic to the core, was ever credited adequately for his acting skill (“merely a movie star”) but he was unconvincing in only one role (as a German naval officer, for God’s sake!), and in every film he made there was never any doubt about what you heard him say. (His masterpiece by the way was The Searchers. But I’ve already shared my enthusiasm for it in this journal before: “Cowboys and Indians,” NER, May 2016.)

I don’t want to turn these speculations into a mere listing-with-comments of my favorite movies, but I do have my pleasant memories. Another artist never incomprehensible was Montgomery Clift, who played a German victim of Nazi medical brutality in Judgment at Nuremberg. When asked during testimony the merely incidental question of his father’s politics, Clift doesn’t pronounce Communist in the American or English style “KAHM-yu-nist” but bothers to say with German appropriateness “Koh-mu-NEEST.” A small point, but telling.

Most of the recent films I have thoroughly enjoyed have been in a foreign language. I know some Spanish, I know some German, etc.—but I know no Danish, for instance, so I cannot swear that the verbal clarity of these films (one reason I prefer them to recent American or British) is because the actors know how to speak. No. In spite of some Spanish and some German I am relying primarily of course on reading the English subtitles below. That’s O.K. But what am I to think of the habit I have developed of calling up on my TV monitor English subtitles for movies in English? A damned shame is what I call it!

Something culturally significant is going on, something which includes acting styles, but more than that. Call it, ironically, an “artistic” distrust of art. The way I think about it is perhaps conditioned by the fact that for years I professed the philosophical discipline of Aesthetics, and Aesthetics was understood both as the philosophy of art and the study of beauty: the assumption being that the beautiful and the artistic are twin concepts. But philosophers—whatever Plato wished—don’t rule the world, and certainly do not rule the art world. There the practitioners of art and the critics who want to be “with it” rule. And, now, beauty is not a requisite. Think, for example, of the celebrated crap of Jean-Michel Basquiat (whose visual drivel I most recently saw displayed in the Yale University Art Gallery). In the artistic world of “withitry” (a word invented by Joseph Epstein) not only does art not have to be beautiful, it doesn’t even have to be particularly artistic. One extreme example is “erasure poetry” (you can find it occasionally in the magazine Poetry) in which the “poet” has found a piece of writing, erased part of it, and published the rest as a poem. So, my locution “an ‘artistic’ distrust of art” is not as absurd as it sounds.

My own view of aesthetics is strongly influenced by George Santayana’s The Sense of Beauty, a wonderful book in which Santayana likens Aesthetics to Ethics, twin disciplines, as it were. I extrapolate: In Ethics, the philosophy of proper moral/ethical behavior, you don’t (or you should not) say that any behavior, any choice, is as good as any other—that it “just depends” on whatever). In Aesthetics, the philosophy of art and beauty, you don’t or shouldn’t say that any work of art is just as beautiful or not as any other—it just depends, etc. And just as there are vile unethical choices and actions, there are creative works which are devoid of beauty, ugly in fact. Which means to my mind—as the twin disciplines are yoked—just as you would not want to call a vile action beautiful, you cannot call the intentional creation of a work of art devoid of beauty ethical. So not only is the stuff Basquiat paints trash, the creation of it is itself an unethical and immoral act. Perhaps I am being too extreme? I don’t care.

Now, maybe I ought not be so harsh when speaking of the actor who avoids the kind of beauty that is clarity for the sake of the “new theatrical aesthetic” as I have dubbed it, or the director who instructs the actor. Okay, maybe I shouldn’t be so harsh, but I call his or her or their theatrical choice unethical. To hell with them! I hope it is understood, appreciated, that my anger, as it were—rather than being a mere response to Brook giving me the worst evening in the theatre of my life—is founded on philosophical grounds.

Now, if there’s something culturally significant going on—as I’ve put it—there’s something significant missing as well. What? Poetry, that’s what. I beg the reader’s indulgence as I continue with these aesthetic speculations.

Among my favorite films is Wim Wenders’ 1987 Wings of Desire (German title Der Himmel úber Berlin). An angel, Bruno Ganz, longs to become human, in part because he has fallen in love with a French trapeze artist, Solveig Dommartin. Such a transformation can happen on occasion: note the American actor in Berlin making a movie, Peter Falk (playing Peter Falk) who senses the presence of an angel about to do what Falk himself has done. In a kind of subplot, an elderly gentleman Wenders calls “Homer” wanders, silently declaiming, through libraries and vacant industrial lots. Much of the earlier moments of the plot involve Ganz and a fellow angel, Otto Sander, wandering about doing what angels do, observing, occasionally intervening in human events unbeknownst to the human. In the “theology” of the film, angels are not people who have passed into an afterlife, but heavenly beings who have been here eternally. Already the film is “poetic” in concept, if you will. But in language as well:

First, whether Falk in English, or Dommartin’s French soliloquies, or Homer’s (Curt Bois) speculations, or Ganz’s and Sander’s recollections, the language is so clear (I mean you hear every single word even if your understanding of them depends to varying degrees upon subtitles). Second, much of the film—as when Ganz and Sander are remembering what things were like aeons ago, as in “Do you remember when the bee-swarm came?”—sounds like poems being declaimed. And in fact some of the film is poetry! As when the narrative voice-over is a poem by Peter Handke.

Als das Kind Kind war,

ging es mit hängenden Arme,

wollte de Bach sei ein Fluss

der Fluss sei en Strom,

und diese Pfütze das Meer.

So, the viewer perhaps does not know German? It doesn’t matter. The words sound stunning and the recitation is lovely. If you haven’t seen Wings of Desire, see it!—you’ll know what I mean. Poetry in my meaning is rhythmically distinctive language, of necessity heard and not simply lying visually on the page.

If I may make a grand aesthetic/philosophical proclamation, all great literature aspires to poetry! Perhaps, then, one problem is that under some new cultural dispensation drama, whether on stage or in film, no longer aspires in the first place even to literature, only to some visual spectacle?

The conversation reaches its peak and a kind of unexpected but nonetheless inevitable poetic moment when, after the tide has receded around the mount, Heard recites—after so many intellectual questions—Pablo Neruda’s poem of odd queries and striking metaphors “Los Enigmas,’ which begins with

You’ve asked me what the lobster is weaving there with his golden feet?

I reply, the ocean knows this.

You say, what is the ascidia waiting for in its transparent bell?

What is it waiting for?

I tell you it is waiting for time. Like you . . .

and concludes stanzas later with

I am nothing but the empty net which has gone on ahead

of human eyes, dead in those darknesses,

of fingers accustomed to the triangle, longitude

on the timid globe of an orange.

Heard’s reading is sensational, and can be found, in fact, on you-tube. If I am right—or, rather, since I’m right—that great literature aspires to poetry . . . I don’t need to finish that sentence. In any case, Mindwalk contains one of the great moments in film: comparable in my mind on its walk with the moment in Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994) when the lover of the deceased recites at funeral W.H. Auden’s “Funeral Blues.”

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.

Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead

Scribbling on the sky the message “He is dead.”

Put crepe bows round the white necks of the public doves,

Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves.

He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest,

I thought that love would last forever: I was wrong.

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun,

For nothing now can ever come to any good.

No, of course I don’t mean to suggest that a great movie needs to contain an actual poem. Although it’s a bonus. Twelve or so years ago Christopher Plummer gave a poetry reading at the Westport (CT) Playhouse: Lord Byron and other beloved chestnuts. It was my impression that the audience, transfixed, was resistant to leave the theatre after the reading was over: of a certain age, with a smattering of younger people, they seemed especially moved to be reminded how poetry had worked upon them when they were younger and in school. They may have attended just to hear Plummer in person, but had received a bonus. A year or so later I heard Sam Waterston reading classic poems in a church in Cornwall, Connecticut. A similar effect—which Broadway and Hollywood producers probably cannot imagine.

Read more in New English Review:

• Surviving the Journalism Bug

• The Analog Imperative

• Sally Rooney’s Palpable Designs

I’m not sure how these experiences square with the fact that stage and screen audiences don’t seem to be in rebellion against in- or barely-audible dramatic productions. Perhaps the transition from traditional clarity of dialogue to realistic approximations of casual carelessness has been so gradual that most haven’t noticed it or have simply forgotten how professionals like, say, Bogart used to speak, or perhaps there are sufficient numbers of audience young enough never to have known anything else so can’t notice. In any case, when we saw Peter Brook’s production of Peter Brook’s creation, The Prisoner, the only complaints I heard from the audience afterwards were that, as the actor stares at an imaginary prison for an hour, nothing much was happening (and it truly was boring!) Or perhaps some of the audience were cowed by reports of lavish praise in reviews which celebrated nonogenarian Brook’s turn as playwright after so distinguished a career as director. Maybe, now, if tone, mood, atmosphere can be conveyed by gesture, words no longer matter. In which case, drama, whether staged or filmed, is no longer literature.

Odd, a couple of days before I began this essay I read the great Dutch actor Rutger Hauer’s obituary in the Times, July something. Odd because recalling Hauer some time before was a catalyst for my thoughts.

My film tastes are not particularly outré. I adore Bergman, Fellini, several Shakespeare films (among which Branagh seems ubiquitous), classics like The Best Years of Our Lives and Gone With the Wind (a film now not judged “safe” for Ivy League undergrads). I hate to go on for fear of leaving something out by memory lapse. When I play “Your Favorite Movie” I may run up to thirty or so, but when I get it down to a handful, two are always there revealing my eclectic taste: The Searchers and Blade Runner, Ridley Scott’s 1982 masterpiece.

I don’t have to know why a blade runner is called such (I don’t) to know that Deckard (Harrison Ford) is right for the job—which job is to seek our “replicants” and “retire” them. In futuristic LA, four bio-engineered cyborgs, physically not distinguishable from humans, have escaped from outer space (“off-world”) where they are supposed to perform their tasks and have gotten back to earth. Physically stronger than humans and just as smart or more, they are judged to be potentially dangerous (and are!). Knowing that replicants only get more dangerous with age their makers have made them safer with a four-year life span. Deckard’s job is to wipe them out now, and as the film approaches its close (after a remarkable plot I hope enough readers already know) three are dead, but not the leader Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer of course). There are several “cuts” made over the years. Some critics in the “industry” (ugly word for what should be an art world) evidently objected to Ford’s voice-over narration—after all, it was made of words. But I’m satisfied with the film as released in ’82.

We can thank the Lord—or just Ridley Scott himself—that the director did not say to Hauer something like this: “Rutger, dying people don’t speak too clearly, so adjust your speech to that fact.” Instead: In one of the greatest scenes in cinematic history—at the end of which, the story goes, the film crew was in tears—Hauer, with apparent difficulty catching his breath after each clause or sentence, says lines which evidently were his own creation, with deliberate clarity:

I’ve seen things

you people wouldn’t believe.

Attack ships on fire

off the shoulder of Orion.

I watched C-beams

Glitter in the dark

near the Tannhäuser Gate.

All these moments will be

lost in time,

like tears in rain.

Time . . . to die.

If, indeed, drama is literature, and all great literature aspires to poetry, Blade Runner, thanks to Rutger Hauer, is, metaphorically, a perfect manifestation of this aesthetic truth.

There is a sequel to Blade Runner produced 35 years later, Blade Runner 2049. I have not seen it. And, frankly, for reasons probably obvious, I am afraid to.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Samuel Hux is Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at York College of the City University of New York. He has published in Dissent, The New Republic, Saturday Review, Moment, Antioch Review, Commonweal, New Oxford Review, Midstream, Commentary, Modern Age, Worldview, The New Criterion and many others.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast