Whom the Muses Choose

by Justin Wong (August 2020)

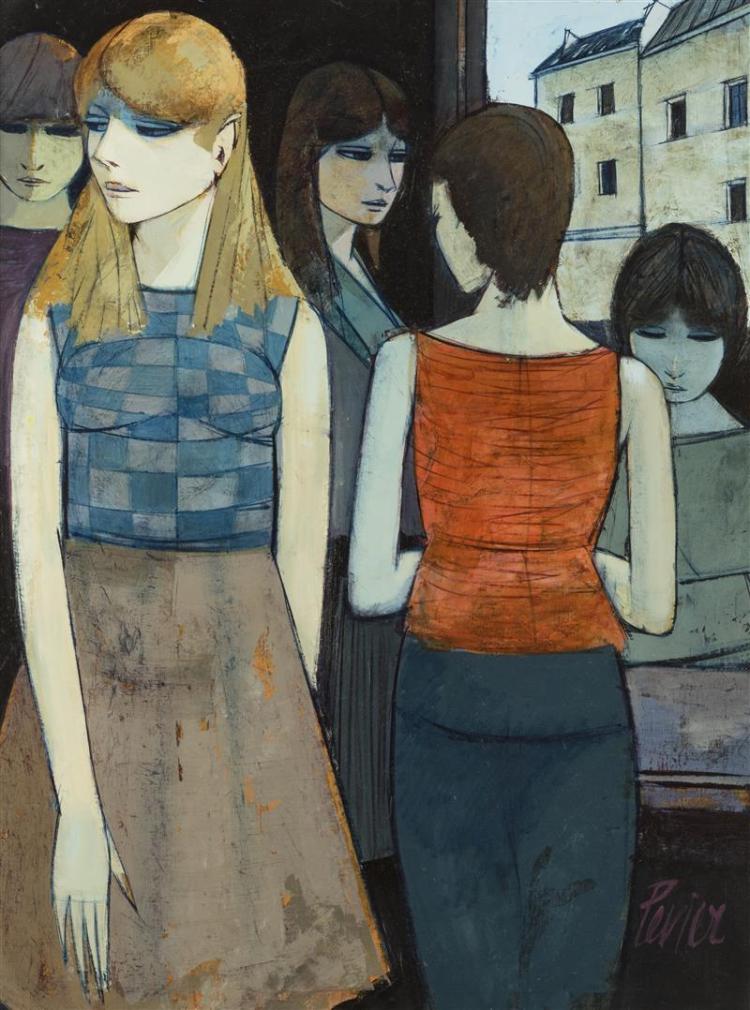

Femmes, Charles Levier, 1960s

In my eighteenth year, in the period of my life when I was entering into higher education, my sister had it in her mind that she wanted to be an artist—a writer, someone who composes tales and poems.

This was a shock to me, to our parents, who were encouraging of all that we did or chose in life. Perhaps the reason we found this so, was because that she showed little interest in these things in the years leading up. No one could say she was in the least bit artistic, or destined to live such a life, or possessed such talents, a soul that had vision, insight, what the Greeks called memory, who communed frequently with the daughters of Mnemosyne, the muses.

I had my reservations about my sister’s sudden transformation, thinking it a fad, something she would grow out of when it was clear she showed little or no aptitude for such a calling.

As it was, I was not impartial, for one thing I was wildly envious of her, her looks, her brain, her accomplishments. She was perfect in almost every aspect of her being. She got As in class, she was amongst the most beautiful in her year group at school, and managed to drive all of the boys crazy with desire, dozens pursued her, wishing to have her on their arm, and consequently, to win her heart.

With this being so, she had a full social life, and outside of study, there was often plenty for her to do. When weekends came around there was always a party that she was invited to, that took place in an empty house of a student whose parents escaped town for the weekend, or in the park under the cover of starlight, where those of her age—which was under the legal age of drinking—could get drunk so their faculties were dulled, and inhibitions lowered. This was away from prying policeman and parents, guardians and elders who found it disappointing that there was nothing to do aside from this base and debauched act.

On weekends I partook in none of this, the drinking, the partying, the having fun. Instead choosing to spend my time engrossed in a project that needed to be completed for the coming week, or would watch sitcoms with my parents, joyfully indulging in old favourites, ‘Everybody Loves Raymond,’ ‘Steptoe and Son,’ and ‘Hancock’s Half Hour.’

Besides, I did a fair bit of partying in my younger years, when I was still in high school, when I was as old as Sophie my sister. Now I was in sixth form, and getting ready for University, and would soon evade the lives of all those near and dear to me, moving into a freer existence. I was applying to Universities in disparate parts of the country, with the hopes to train as a nurse. My job would be a nine to five that would pay adequately. This happened to be the extent of my ambitions, not wishing for stardom, nor artistic fame, nor any other undue, spurious accolades such as my sister craved overnight.

I think that what possessed her to do this was an English teacher she had, Mr. Eliot, who inflamed her of a love of literature, and encouraged those that he taught, to write, to show him their work. I think there was a creative component to the course which he taught, though the writing that the students handed him, – in which my sister was one, was extra-curricular. At the dinner table, she did nothing but talk about this man, with his passion, his teaching style, his infectious love of language and literature clearly rubbed off on those around him.

One day fresh from handing this Mr. Eliot one of her poems, she proudly told us-the rest of the family that he loved the thing she wrote, that she showed great promise. I wondered even then, if what he said was true, or if he was just humouring her in her sophomoric attempts, the emotional ramblings of an adolescent, with undeveloped sensibilities, a limited worldview. From then on, her life changed drastically, from the studious beauty she had been, to something all the more bohemian. She bought second-hand classics, bringing home, The Complete Poems of Tennyson, The Selected Poems of Yeats, Stories of Henry James, and the novels of Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, and Gustave Flaubert. Material of this weight went against the grain of the kind of books we had in our house, our meagre bookshelf in the dining room, filled mainly with manuals and third-rate thrillers. Ours evidently wasn’t an artistic house, one that engaged in more sophisticated cultural pursuits.

Maybe it was because our parents had little in the way of a formal education, they both left school at sixteen, waltzing into the commercial world of work from the moment they were capable. Both my parents wanted my sister and me to go to University, to have the kind of experiences that were closed off to them, as they were told to leave school in mid-adolescence.

Perhaps in regards to my sister’s ambitions, that of artistic renown, her worldview seemed limited even for her paltry years, in a way mine wasn’t. No one could say she didn’t have something of a charmed existence, a joyful and full social life, where she commanded the attentions of those who were popular, the attentions of those who were beautiful. This Mr. Eliot, the man she spoke of, was someone who she was smitten by, and developed something of a crush on, was incredibly different than the men she usually hung out with, members of the football team, or other such meatheads. He was evidently artistic, cultured and sensitive, and encouraged her to explore a side of life that was near impossible to see in our miniscule and inconsequential town. I wondered why she liked him, why it was him of all people to enflame her rather than those of a similar age, the boys of her year group, who would devotedly do anything she asked of them, as if she was a deity in her own cult. Perhaps she possessed something that is common to all or most who have ever lived, desiring that which was closed off from her.

When the following September came, I made my way out of the town, during Autumn’s first flush, with the skies leaden and the streets leaf strewn, where the heat of the previous months had waned, like a radiated house, whose boiler had been turned off. The previous humidity cooled down to its natural temperature over time. I personally preferred the coolness to the heat in unbearable measures I was condemned through summer to endure, the wind and the rain. The coldness reflected something of myself.

Escaping off to University was something that gave me a great deal of relief, seeing as the life that I was born in to, that of being confined to live in a town with the populous of a few thousand, was soon to end, and I could live my life out as I wished.

This was frightful and liberating at once, I had to adjust to the life where I had none telling me what to do, as well as make friends and boyfriends. The first few weeks in the halls of residence, the new campus, was exciting, there was always a plentiful array of activities to indulge in, with parties, with clubs, and above all, with drinking.

This hysteria, the general sense of excitement of our first weeks seemed to die down, where everyone seemed to find themselves in the rhythms of scholarly life, attending classes, preparing for exams, beavering away at coursework.

There was some who I grew close to, a girl who lived in the same halls, we seemed to have the same dour demeanour, personalities attuned to pessimism. The more I got to know her, the more I thought that she was troubled and, although the troubles I faced were due to my sister and the ease in which she floated through life, Bonny, my newfound friend, seemed to have experiences that were horrific. Whilst growing up, she moved around a lot, going from town to town as if she was a gypsy. This incessant travelling where, as a result she felt most at home on the road, was due to her mother who seemed unable to hold down a relationship. She went from boyfriend to boyfriend, from married to divorced. She enlightened me on her situation, the more we grew closer, telling me of her strange experiences, the abuse she suffered, both physical and sexual, at the hands of the transients, her would-be stepfathers.

Up until now, those like Bonny, were often talked about but never intimately known. The stories, as horrific as they were, were read about in papers, or seen on the screen. There was a chance I met people like Bonny in high school and sixth form, those whose lives consisted of equal experiences, but they never let anyone know they were suffering. Rather they hid these displays by acting out, excessively drinking, doing drugs, by sleeping around.

When Bonny and I grew closer, well-closer than we had been on our initial meeting, I thought that she would be the sort of person who was dangerous, disastrous to know, that she would drag me down so that my psyche would be of a similar state as hers. Nothing was further from the truth. She was nothing if not kind, if not pleasant to be around. The experiences that she had, where her life was lived: here, then there, gave her character, sweetness, and a vulnerability that the others, who came from wealth and privilege, seemed to lack.

I spoke frequently to my parents and my sister. They checked in on me to see if I was enjoying myself, making friends, going to classes and doing everything that needed to be done to earn a good degree. I let them know that I was doing fine, and I was settling into my new life, the carefree one of being a scholar. Sophie emailed me frequently, which was nice for her to do. In this juncture in her life she was still writing, and she made it her duty to send me her poems and stories. Things such as this held my interest only so much, not that I was an expert, or a professor, though I enjoyed to read.

Some of the lines of poetry were good, others not so, so that what she wrote failed to come into something of a cohesive whole, and that which wasn’t above all things, sentimental. I tried to convey these thoughts and feelings to her, that she would hopefully grow better in time, when she was educated, and possessed the maturity that comes from experience.

Meanwhile, Bonny and I often spent weekends together, she had friends in the city who went to this dive bar that played hard rock and sold hard liquor. This music was not the kind of thing that I cared for if I was being entirely honest, though Bonny’s friends were most accommodating and easy to talk to.

It was in this period I was introduced to her boyfriend Ian. He happened to be someone who she met recently through her friends, at a house party, so she told me. I had my reservations about him, he was bad news, rough around the edges, drank worrying amounts, and took pills. Having him as her lover was destined to sadden her greatly, and I was concerned that her life would become a mirror to her mother’s. I chose not to make these reservations known and kept these thoughts to myself. There was the possibility that their relationship wasn’t serious, that she would be able to slither like a worm out of the wet sod from underneath him.

I still liked her. Being in her presence was uplifting in a way that being in my sister’s wasn’t. Perhaps because she wasn’t so spectacularly better than me, which wasn’t to say that she was worse, but that we were social equals.

I didn’t know her mother—her history was relayed to me through hearsay, where the tales of her horrific choices and sorrowful existence were told to me by Bonny. I was willing to bet that this boy she met, the one who to be seemed eerie to no end, was the kind of man her mother went for: disreputable, disappointing, someone who was destined to upend her life in time.

This gave me a divided conscience about my sister Sophie, and the kind of chap she was enthralled by. He was at opposite ends of the spectrum of masculinity than the piece of work that Bonny had affections for. There were perhaps those who were of a similar stripe to Mr. Eliot on the campus, who if I introduced Bonny to, would dismiss as being unworthy of love. Perhaps men like Mr. Eliot—the man who transformed my sister’s life, that now she wrote poetry—are men to be admired at a distance, they are forbidden loves, who for Sophie, was out of his league and age bracket. Maybe if she was a similar age to him, and easy to attain, she would eschew his advances along with the others, the football captain; the Rugby Player; the guitarist; and the star student.

The more I got to know Bonny, the more we hung out in our free time, the more I could see that there was something troubled about her and that these problems that she had weren’t limited to just her family life, but that she contained an unnerving darkness. When I checked in on her, knocking on the door of her room, I could see that she was drunk, or getting drunk, oft by herself. It must be noted that I was in no position to moralise, to tell her how to live and, though I never got this spectacularly drunk when alone and studying, I still indulged in alcohol and consumed copious amounts. I enjoyed her company in this context. When we weren’t out on the town, wearing makeup or struggling to walk in high heels, we would listen to jazz and pop from a previous time, the 50s, the 60s, and the 70s. She had a diverse taste when it came to the music she played, and such that we danced to in her room, from the blare of her slight though voluminous system. She introduced me to the sullen sounds of Billie Holiday, the more uplifting though equally serious Nina Simone. If she was in a more joyous mood, she would play Cher, Roberta Flack, or Carole King, music I never really heard before, but seemed to be superior to the music of the day, the songs others played.

“Do you know I play music?” she said to me one day.

“Really, what do you play?” I asked her as if I couldn’t quite believe this was so.

“Well, I sing and I play a bit of piano,” she said relaying this to me, “One day I would like to be a professional.”

I didn’t know what else to say to this, I had to suffer my sister’s delusions, reading her writing. I personally had enough of artists, creative types, those chasing after acclaim, the love of a crowd. Bonny was studying design; she evidently didn’t think much of her ambitions as a singer to pursue them in education. People like this, those with dreams of stardom seemed to be legion in the place I found myself, higher education. The faculties seemed to humour those naïve enough to swallow their lies, to give up three years to study music, fine art, and creative writing. The truth of all of this was that only a blessed few could make it so as to justify its existence. The rest would doubtless end up debt-ridden and bitter after they had grown privy to the deceit.

Regardless of these reservations, we went out together to places we were known to frequent, in dive bars and student socials, from time to time her boyfriend went along with us, seeing as he hated Bonny going out by herself, without her by his side.

“So, he’s jealous!” I said to this, as if seizing on whatever fault I find in him, which I must admit, were plentiful.

“Well, you know, he said that he is just uncomfortable with the thought of me going out to clubs with a load of horny teenagers around.” She told me.

“Well, if you don’t trust each other, is it really much of a relationship?”

“Yes. I mean, you know he just wants to spend time around me, and make sure that I’m safe.”

“Really, thousands of girls go out all of the time, they don’t need a guy around them every time they go to the town centre,” I tried saying to her, though I was really aware of how I came across. But it was never my intention to create a rift for the sake of creating a rift, as I couldn’t really imagine her life being one of joy with this creep hovering around.

“Anyway, why don’t you have a bloke?” she asked me, “You know some of the guys I know, that are friends of Ian, think your quite cute. We’ll have to double-date some time.”

“Yes, perhaps,” I said thinking this was an empty promise, which it turned out to be.

During the first term there were a few exams, and I managed to work hard, also preparing diligently for my placement in a hospital affiliated with the school, where I would put all that I had learnt thus far to practice, attending to patients, checking blood pressure, doing tests, absorbing all from my environment, like someone deprived of oxygen gasping for air.

I had weeks off to myself at Christmas and I went home, the place I had been away from for three months. There was something in my return to the hearth of my home that filled me with a comfort and joy, such as I hadn’t experience as a student, or found in the drab and dreary room in the halls, that I left in the morning, and returned to when the blackness of evening arrived. Perhaps it was because it was filled with family, with those who I loved.

I enjoyed seeing my sister again, and witnessed a change in her appearance. She seemed altogether more mature. She was still reading, spending her evenings engrossed in this most solitary act, and told me of all of the wonders discovered, the literary gems she had the pleasure of experiencing. The works of Shelley and Byron, Sylvie and Bruno by Lewis Carroll, The Tales of Edgar Allan Poe. She even seemed more bohemian, and took on aspects of that sensibility, in her previous appearance that was coated in make-up, making way to her natural beauty, the clothes she wore were those from a different era, the dresses, the shoes, the jumpers. Things bought along with her books from charity shops, places she spent hours lost in, during her free and itinerant weekends.

When she wasn’t doing homework, keeping up her sparkling academic record, she was writing stories, things she passed my way. Such things had one or other favourable aspect, there was a nice turn of phrase, or her use of language showed a modicum of sophistication. But they contained no deeper meaning beyond being words on a page. She was still young, and there was still hope, she had her life in front of her, and experience to gain.

We spoke, and I enlightened her about my life as a student. This new aspect of my life thrilled her greatly, as she knew no one who ventured off into the world of further education, who escaped home so as to study. I told her that I was having a good time, I made friends, that there was always plenty to do, particularly in the city that was my home. But she seemed to have what might be characterised as a dead archaic view about what the life of the student consisted of.

“So, what you guys talk about? Do you discuss philosophy, plays, and ideas?” she asked as if she couldn’t wait to go, to see if the reality lived up to its promise.

“Well, there’s more talk of fellatio than philosophy, more talk of foreplay than stage plays.” I said wishing her to know the truth of the kind of things that went on in academia.

“Really?” she asked, sounding somewhat surprised, “So it’s not that much different than school.”

“Yeah, except you don’t leave school £30000 in debt.” I said.

These things saddened her deeply, and perhaps my little sister was filled with the thoughts that on leaving this town for higher education, she would meet people that were high-minded, who would talk till the morning’s early hours on the existence of God and epistemology, on classical economics and classical Greece. This wasn’t to say that it couldn’t happen, seeing as there were plentiful societies, people who met around things they showed interest in. The culture may be different in more reputable establishments, that you need a flawless academic record to attend.

During my time back home, during the heart of winter, I spoke to Bonny. She was doing great, and spending time with some family; a sister, or so I am told. She was rather vague as to the particulars, about where she was going, who the people she was spending it with were. Every time I brought up family to her, she seemed to speak fleetingly about them, as if this was painful for her to do.

I made my way back to school, after the carol services, the visiting of our extended family, Christmas day, Boxing Day, New Year’s Eve, and New Year’s Day. Me leaving my hearth, the people who were related to me by blood was saddening in itself, though I loved my life as a scholar, my flourish into self-sufficiency.

In the new year and term, I once again met Bonny, though she was down and deeply depressed.

“What has happened?” I asked, wondering what happened to transform her state of mind.

“It’s Ian, he cheated on me, with that cow Cara.” It took me a while to remember who she was referring to, a girl who I briefly met, who seemed to be a part of the same circle of friends.

“Well, I tried to warn you about him,” I said trying my best not to gloat, as it did nothing to alleviate her pain.

“Yes, maybe I should have listened to you.” she said, which was nice for me to know, that she valued my wisdom and insight.

I stayed with her a few days, being by her side, trying to support her through this ordeal, and in this period, she did seem to pick up. At least picking up from someone who looked as if she could have easily hurled herself from on top of a roof, to the mild pessimist I knew when first we met.

It didn’t take a long time for her to pick herself back up, where she once again attended her lectures, handed in coursework, and prepped for exams. The campus where she studied was relatively close to the halls of residence, so it didn’t take much effort for her to walk there and back, staying for two or so hours a day so as to attend lectures. Sometimes, she stayed on campus and went to the library so as to study, past the period when the sky had been covered in a cloak of black, which in the winter months, wasn’t too far into evening. At times I returned back, and when knocking on her door, there was no answer. I thought she might be out, on the town or in the student bar, getting over her broken heart, with booze and boys. Her life went the opposite direction in the wake of her misfortune, her previous circle of friends depleted, so I was the only person she had left. Her life of here today gone tomorrow affections and deadbeat boyfriends dried up. So that now she resembled someone who had a balance to their life.

Things went back to how they had been, Bonny and I going out about town, or spending the evenings indoors, watching a film, listening to music. In time, she was unrecognisable from the wreck she was in the aftermath of her deceit. Time, the greatest of healers, restored her to the person I once upon a time knew, before her boyfriend lived up to my worst suspicions.

She talked more of the aspect of her that I was slightly sceptical about, her wish to perform, wanting to get a group of musicians together—a task that wouldn’t be so arduous in this city of a million souls, its thriving music scene, with clubs and bars dotted about the place. I must admit that she picked up whenever the possibility of singing, or music in general was mentioned. In such instances one wouldn’t have noticed that she just suffered greatly, that her life was one of dashed hopes.

She texted me one evening and asked me if I wanted to get a drink in this bar that she would be singing in. I said that I would be able to make it. I never heard her sing, but she was obviously musical, and blared music out in her room, having a sophisticated sonic palate for her years. I had to wade through the plethora of pages my sister produced, watching her sing could be as dreary as that, where all that was concluded that she showed no gift for musicality. But perhaps this was my cynicism talking.

The bar was moderately packed for a mid-week evening, there were numerous folks dotted around the place, drinking pints of beer, glasses of whiskey and of rum. I saw her there, we hugged, and she told me to sit down. I went to the bar to get a drink, with the room blackened, its candles in jars provided the mildest of illuminations. I knew not what to expect, looking over to her, she was being accompanied by a guitarist, someone sat on stage to the righthand side of her.

She began to sing, a few pop tunes—tin pan alley numbers, and I thought sang them in a way that was previously unrecognizable to me. I noticed some of them, her playing them to me in the evenings, when we hung out and relaxed in her bedroom, with song being played softly in the backdrop whilst we chatted amongst ourselves. They sounded different, elevated even. It wasn’t so much as she sung the words, though they seemed to come alive, to move me in a way that I had never been moved before by art, by music. I stood there dumbfounded, having something of an otherworldly experience. The dimness of the room was needed, for I happened to see colours, bright and vivid as tropical fruits, and the sweet-sung melodies wove to me tales of agony, fables of a love forbidden. Through this seemingly strange, insignificant experience, I was transported into worlds I never knew existed, lived lives that weren’t my own, and recollected memories that were not of my experience. Seeing her stood up there under the bright glare of spotlight, she seemed as if not uttering words, nor making sound, but as in love, she was giving away a piece of her soul, that had been trod and trampled on numerous occasions in the brief moment of her life thus far. Hearing this performance, she was someone for whom the muses congregated around, that blessed her with vision, insight, the ability to see that which wasn’t visible.

I told her my truthful feelings about her performance, that I was haunted, and deeply affected by her talent, as were the attendant audience, if the cheers were anything to go upon. I thought back to that moment in the ensuing years of my life, me traipsing there on my lonesome in the black of evening; my meeting her there in that darkened, indistinct place; her captivating performance, in lines that were subtly articulated and embellished; and our returning back to our residence around midnight, when the world in its commotion died down to near non-existence. For a moment I saw only that which has suffered can see, things such my sister never had known nor ever will know.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Justin Wong is originally from Wembley, though at the moment is based in the West Midlands. He has been passionate about the English language and Literature since a young age. Previously, he lived in China working as an English teacher. His novel Millie’s Dream is available here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast