Why I No Longer Self-Tape

by Wyntner Woody (July 2023)

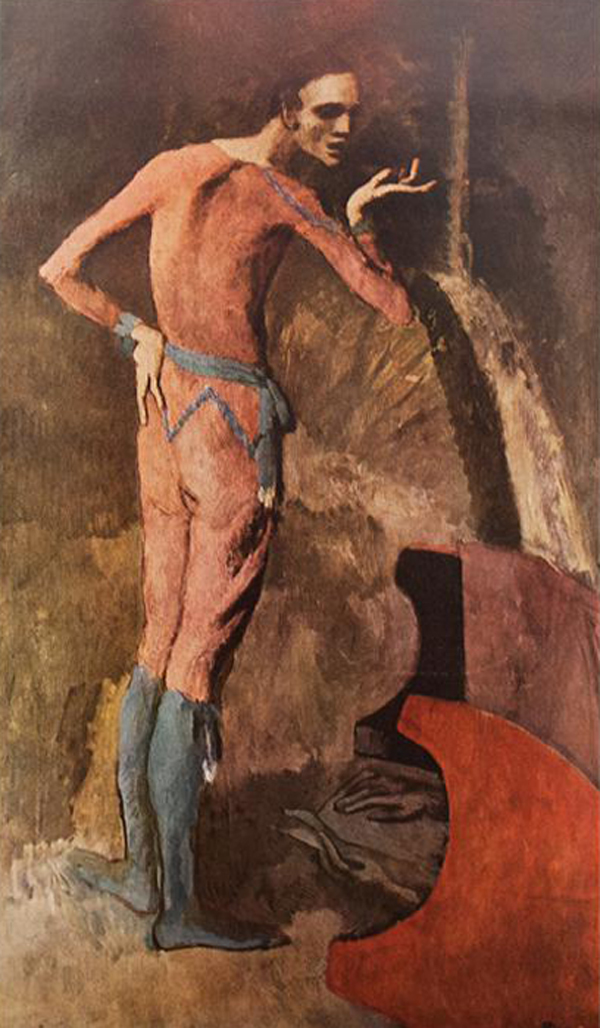

The Actor, Pablo Picasso, 1904-5

In a class for SAG-AFTRA actors I attended, Richard Robichaux elucidated a premise of acting: a joyful giving. He reminded me of how I once approached character acting. But playfulness and gratitude elude me now; rather, burden and disenchantment become my salient sentiments, especially when self-taping video auditions. Several years ago, I’d had enough, deleted my Actor’s Access, Casting Networks and Backstage accounts; I haven’t self-taped video auditions since. I attended Richard’s class to see actor friends I haven’t seen for a long while. But my attendance was providential because it catalyzed a realization stewing within me. I now know what I have given up or forsaken; and what I have gained thereby.

In a stage audition, one knows one has landed (or not) by sensing the audience, even if only one casting director may sit before you, to read the room and adjust, to play to response, enlivening the performance. Live theater is dangerous, like tight-rope walking, enlivened by the anticipation that an ephemeral performance is never the exactly same twice, for both audience and performer. But in a self-taping at home without a reading partner—the lonesome result of an inhuman technology now unfortunately well-established—not only must one imagine the character himself, but the line-readings of ghost-actors, before an audience of furniture. One must fill in all the blanks oneself. As Richard Robichaux said in class, well, that’s just the way it is.

Orson Welles once quipped that even Rin-Tin-Tin can act in a close-up. We seem to be awash in them. They are easy, thoughtless things. They do not show the body. Alexander technique, an essential part of theatrical training neglected now for many decades in the US, demonstrates that the entire body is the instrument: Whole humane meaning—what we express in every personal interaction with another person in real life—can not be conveyed theatrically solely by the human head. In these close-up, two-dimensional self-tapes, three-quarters of the actor’s instrument—casting directors ask for shoulders up—is unused and unviewed. The meaning of the whole human being is expressed selectively and only partially. When wielded in this way, the camera is the enemy of the actor. After several hundred self-taping sessions, this is how I’ve come to see the camera—rather than friend and colleague as I see the theatrical stage. I agree with Welles: The long shot—the staple of live theater, in which there are no close-ups—proves the actor.

Monologues in front of a black scrim on camera can succeed, such as Damian Lewis’s brilliant recital of Antony’s funeral speech. But, for me, they are rare. At its heart, the close-up is an invasion of the character’s privacy, the penumbra of which ought to be stolen (intentionally) by the camera only as rarely as we might catch a glimpse of in life. A handful of self-tape auditions I did were monologues. My final self-taping was yet another multi-character scene. I literally threw up my hands and said, “Basta!”

Perhaps I would have found a way to somehow address and endure these obstacles had the roles and the language used to convey them been worth the while.

A role well-played is often the result of an internal debate—the character arrives after a tortured labor and a breech birth into the consciousness of the actor. Several years ago, at the Unity Theatre in Brenham, Texas, I played Jack Jerome in Brighton Beach Memoirs. Even two weeks into rehearsals, I struggled to discover a reason to enact the role.

Neil Simon never gets at the root of the matter. What passes for humor in his writing is a nervous avoidance of what he ought to be getting at in seriousness. This theatrical cowardice is evident in the play: the boy, Eugene, whose story the play tells, and his father. Jack, never have dialogue together. Simon decided that theatrical neglect was somehow the best demonstration of aduIt Eugene’s imagined recollection of the decades-past distance between them. It does not matter that some fathers and sons speak little or never; the imagined world of the stage follows its own laws. In fact, Simon wrote several pages of dialog between Jack and his older son, Stanley, which I mined for meaning. But he foreclosed an inquiry into Jack which that dialog with Eugene would have readily exposed, more meaningfully and memorably to the characters themselves and thus to the audience. Instead, he delimited interpretation to the stitching up into a patchwork of partial clues scattered throughout the lines. When a writer refuses to delve into an essential aspect of character—or when the limitation of his ability precludes it—what can the actor do?

As a young man, I would have simply affected the accent of a Brooklyn Jewish man of the 1930s, trod the stage in period costume and passed myself off as a cardboard cut-out. But that is not an option at my age of 60. Is a man’s life only the mouthing of empty words or is every breath pregnant with meaning within us? If I am to fake something, it must be true at its heart. This is the role of theater: knowing falsehood in the service of Truth, absolute, objective and unopposed. An actor who does not discover the core of Truth deep within himself, externalized into the character, is simply enacting a fraud and faking it in a way the audience senses at some level is untrue. The spell is spoiled. There is no benefit to the world in that kind of a performance. For the brief moments this serious world of play is enacted, it must really live and by its living Truth, a precious diamond is given to the watcher in the audience.

To portray him from the inside out, the actor who wishes to accomplish this must discover the inner life of the character. Costume and affect may be aids to the delivery of meaningfulness, but they are by-products. More importantly—it has taken me decades to to learn this—that there must be something in the character I am asked to play which is worthy of portrayal. I considered myself fortunate in this case, because, despite the critical weakness in the play, I liked, even admired Jack, a hard-working, ordinary family man. I wanted to treat him fairly. But how was I to play him?

My bolt-out-of-bed intuition came at 3:00 am. The thread of his being appeared to me, complete. The Jack in Act I, overworked, underpaid and unappreciated, had concluded that God had abandoned him; the Jack in Act II had come to the sadder-but-wiser calming balm of conclusion—after a fainting spell at work that may have involved his heart (again, which Simon failed to clarify) —that all rested in the hands of God and that, in fact, God is good. Aha! Playing him thusly, I could demonstrate a transition in consciousness, meaningfully separated by an intermission, that had, in fact, occurred to me in a similar fashion in real life around the time I was Jack’s age.

A well-known acting coach (not Richard Robichaux) once said to me several years ago that ideas cannot be acted. Nothing could be more wrong: ideas are the only things that can be acted! It’s all about meaningfulness: The idea GENERATES the emotion that is acted so that the actor has an intellectual grounding for the emotional demonstration. With excitement, I realized that I had discovered an interpretation of the Simon playscript which fit both character and action, grounded in my own knowledge and experience. I had found ideas that I could willingly, enthusiastically enact in the form of the character, Jack Jerome, with respect and compassion.

I have not found this to be the case in the auditions I have self-taped. Dickens loved his characters and filled them with a scintillation of life that could be felt even when the reader selects dialogue at random (try it!). But the characters in these sides were sock puppets crudely manipulated into relentless cock-fighting with one another. Even Ibsen would be preferable to read (but only barely). The meaningless Sturm und Drang of an ugly material existence is no reason for joyfulness and gratitude in the enactment thereof.

The language employed was common, unmusical and apoetic, barely functionally literate at times and shockingly peppered with profanity—the crutch of the weak-minded and unworthy of being read aloud. When the imagination is paltry and a writer has found no way to overcome with his vision of the Ideal the broken nature of human existence, he wallows in its ugliness and then regurgitates it.

Who needs that? I do not wish to bring it into the range of view of any human being, that is, without resolving it for the audience before the curtain falls by offering something better. That is the point of Theater: the entertainment and edification of an audience who dearly need it and can enjoy it. Scripts are anti-theatrical when their goals are antithetical to the purpose of Theater: To deliver the best ideas of humanity, rather than its worst, to an audience who can benefit thereby.

The imagined worlds of the virtually all films and television, however, are ugly, base, unredeemed. I have never understood the fetish for Mafia programming. The glorification of the drug dealer is anathema to me, as is the blasphemy of the zombie. The relentless cruelties portrayed in police and prison dramas bring the criminal perversions of the few—imagined, it must be said, by writers who must perversely revel in them—into the homes of the innocent. I wish to never play a role in these nihilistic fantasies, not even for money, and it is a point of pride that I have never done so, nor been asked to. A Falstaff, wholeheartedly yes; a Walter White, never.

This is why I no longer self-tape.

Richard sent us sides for class. I knew immediately upon reviewing it what I had in my hands: yet another exemplar of a scene I now viscerally rebel against playing. In it, an obvious alpha (an overbearing “capitalist”) and an obvious beta (an exploited “worker”) confront one another. The alpha has aggressively “stolen” the work of the people he has paid, getting rich off of it; the beta, lusting for a Park Avenue residence and a private jet, threatens to stab him with a poisonous syringe. The alpha dares him, the beta backs off.

Here, in one tidy little package, were two simplistic dichotomies: the one, ideological, the other. a pocket psychologizing, both of which neglect a spectrum of individuation into the convenience of readily digested coded classifications. The scene was about those most boring of subjects when treated in this way: the animal desire for power over others and the riches with which to satisfy one’s lust for overweening material supply. Uh-oh, I thought, here we go again.

For some reason, I jumped into it, making sure to prepare it as best I could. Maybe I could learn something. Would there be any value, I asked myself, were I to expose my beta character’s venality and weakness? Perhaps not, but since I could find nothing else in this character worth playing, I adopted this as my approach. Let it fail, if it might. I was, in any case, eager to enact it in class to see what appeared and whether my attitude might be somehow improved.

Owing to time constraints, I did not receive notes and due to a camera snafu, my minute went unrecorded. That spared me (and classmates) what was likely to have been an unpleasant viewing of an unpleasant character, unpleasantly played. Certainly, there was no joy in my portrayal, and rather than enacting this character with any kind of gratitude, I am pretty sure it must have come across as grudging. But that is all I had to give. I could not deliver what my teacher had rightly deemed essential to acting, at least, not in this role, much as I had not been able to deliver in hundreds of other self-taped auditions.

Robichaux is an insightful watcher of talent and a spirited teacher. I’m sure he would have made helpful and instructive comments to me, regardless, just as he did for others in class. But, even so, I know what the class meant for me. I was right to stop self-taping video auditions. I was my own proof of the wisdom in so doing.

Donne wrote:

T’were madness now to impart

The skill of specular stone

When he which can have learned the art

To cut it can find none.

I can find none, at present. That’s why I stopped.

And if this love, though placed so,

From profane men ye hide,

Which will no faith on this bestow,

Or, if they do, deride:

Then you have done a braver thing

Than all the Worthies did,

And a braver thence will spring

Which is, to keep that hid.

I have kept it hid. But I think—and this is what Richard’s class taught me—that there is yet a braver thing: to endeavor to find like-minded actors, writers, directors, producers with whom to collaborate on aesthetic, creative projects. Surely, there must be others like me. Let us make our own theatrical worlds. That, to me, would be a joyful giving. That is why I have written this essay. I have begun to search.

Table of Contents

Wynt Woody is an audiobook narrator and stage actor. www.theateroftheear.com