by Daniel Mallock (November 2018)

There are many who know little or nothing about the recent and distant past. They are often disinterested about such things and when pressed can find no value in its study.

Because our lives are linear we can’t escape an essential truth: that an event follows a previous event and that, quite often, new things and ideas are built upon those that preceded them. What came before informs and influences the present and possibly the future, too. Knowledge of those things, people, and events of the past can’t help but shine a sort of light on life and events of today, and what might be tomorrow. This is a simple calculus but all too often ignored. The great challenge is not finding historical things, events, and people to study, but interpreting their meaning—particularly as they might relate to the present.

After the election victory of Donald J. Trump, the country appears to have descended into upheaval. President Trump’s election success was directly due to the functions of the checks and balances system (as represented in this case by the Electoral College) constructed by the founders; the losing candidate soon called for its abolition. Such an essentially revolutionary response to an election defeat is readily understood if the times themselves are seen as revolutionary, too.

When attempting to understand political leaders and mass movements, it is necessary to know what the leadership believes and the followers think they believe—even if they do not clearly articulate those beliefs. Unarticulated, but assumed universal truths that are thought to be understood and accepted by all in a given movement, in this case the American left—around identity politics, rigidity of thought, utopianism, globalism, intolerance to opposition, for example—unite the movement and separate it from the wider world and most certainly from the opposition. Understanding the complexities and hot emotionalism of the current political environment is not difficult if we wade back a little into history.

When former President Obama was a “community organizer” in Chicago, he taught and used the methods of another Chicagoan, Saul Alinsky. When Hillary Clinton was a student at Wellesley College in 1969, she wrote her senior thesis on Saul Alinsky, his organization, methods, and political philosophy. She considered Alinsky a personal friend and he personally offered her a job in his organization. She refused the offer so that she could pursue a “legit” legal/political career as opposed to working within Alinsky’s organization that was dedicated to radical change from outside the system.

“She ‘agreed with some of Alinsky’s ideas,’ Clinton wrote in her first memoir, but the two had a ‘fundamental disagreement’ over his anti-establishment tactics. She described how this disagreement led to her parting ways with Alinsky in the summer before law school in 1969. ‘He offered me the chance to work with him when I graduated from college, and he was disappointed that I decided instead to go to law school,’ she wrote. ‘Alinsky said I would be wasting my time, but my decision was an expression of my belief that the system could be changed from within.’” (Washington Free Beacon, 9.21.2014)

The question, then, is what does a person who is dedicated to radical change do when he/she becomes the president of the United States (Obama)? How far can he really go within the constraints of a constitutional republic built on laws and institutions—which themselves are the agents and means of change (though not as rapidly as he would prefer)? For issues of the present moment, what does the heir apparent of this ideology, and the profoundly disappointed expected holder of the passed torch of presidential leadership (Mrs. Clinton) do when the presidential torch goes instead to the opposition candidate, someone entirely opposed to these Alinsky-oriented concepts of perpetual radical change? To understand these questions and come to some conclusion about them we’re obliged to turn to history for the answers, which are readily available but not necessarily easily understood.

Saul Alinsky is widely known as the rabble rouser defender-of-the-poor and radical change agent from the ’60s and ’70s whose unusual tactics of mass mobilization were often successful, occasionally grotesquely humorous, and sometimes revolting. His books are now considered quasi- “classic” in their genre of political radicalism. The rhetorical elements of the Alinsky approach (demonization of the opponent) have been used successfully by those on the left for decades with some on the opposing side now deploying them to equal profit against those on the left. Ironically, tactical elements have recently been resurrected by Sanders’ supporters in opposition to other democrats.

Alinsky’s biography includes several years “working” among the top echelons in the Chicago mafia underworld. It is difficult to separate the nihilist criminal worldview that negates establishment and law/order from his later approach as a leftist radical activist and theorist who directly challenged the legitimacy of any institution or establishment.

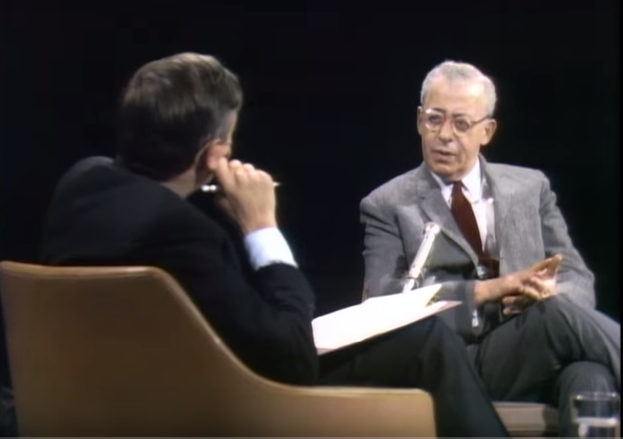

Alinsky’s experience with the Chicago mob seems indelibly etched in his heavy-handed approach to change, and in his confrontational, self-assured, yet off-handedly dismissive manner toward interlocutors and critics in the referenced interview with William F. Buckley. Alinsky’s view of the world and of humanity is not one that most would consider positive or uplifting. It is not a view that empowers peace, cooperation, tolerance, compassion, or consideration of the challenges faced by all parties to any given disagreement. His thoughts about change and ‘power’ are inimical to fundamental ideas of American law, politics, and institutions.

The ideas of ‘60s anti-institution and anti-establishment radicalism are now at play once again, this time fostered not by a fringe radical activist author but rather by a former President of the United States and a former secretary of state and failed presidential candidate and their millions of blinkered followers.

The irony of the situation is only offset by the danger it presents to the open society of ideas and reverence for the constitution and institutions as well as societal cohesion that are the foundations of American political life and national existence. If the ‘60s and early ‘70s were significantly shaped by Mr. Alinsky and his followers, the present moment is the consequence of the ascendancy of his philosophical children.

It is difficult to know if Mrs. Clinton and former President Obama share Mr. Alinsky’s view of human development as described below. The Alinsky method for all its claims of aiding the poor is really a cover for something else entirely—the destruction of institutions and the undermining of societal stability. In a 1972 interview published in Playboy magazine, Mr. Alinsky articulated his worldview quite clearly.

“All life is warfare, and it’s the continuing fight against the status quo that revitalizes society, stimulates new values and gives man renewed hope of eventual progress. The struggle itself is the victory. History is like a relay race of revolutions; the torch of idealism is carried by one group of revolutionaries until it too becomes an establishment, and then the torch is snatched up and carried on the next leg of the race by a new generation of revolutionaries.”

For such an antithetical philosophy to be the moral and ethical guidance of an American President (Barack Obama) and the recently defeated former presidential candidate of the Democrat party (Hillary Clinton) is difficult to conceive.

Early in 2017, a video of William F. Buckley, Jr., a leading conservative, noted intellectual, and founder and editor of National Review magazine interviewing Alinsky on his, at the time, well-known television program Firing Line (Episode 079, recorded on December 11, 1967) was posted to the internet. It is an hour length interview well worth watching as Alinsky illuminates his beliefs and approach quite clearly in reply to Mr. Buckley’s insightful queries, and presents a short period of a sort of entertainment that is intellectually, historically, and politically important while simultaneously enervating and profoundly disturbing.

Alinsky is accused by Mr. Buckley of having a cynical view of life, an accusation that Mr. Alinsky is hard pressed to evade. Mr. Alinsky appears to see the world in Hegelian terms (as identified by Mr. Buckley), in which advancement is made only through conflict and that motivations based on anything other than self-interest are denied. Alinsky explains that “all progress comes as a result of a threat and that the reaction to the threat is where you get progress” (36:35). Not only does progress result only as the consequence of threat, but the acquisition of power also fits the same mold, in his view. “You only get power as a reaction to a threat” (11:10). Perhaps Buckley’s reference to Hegel is improved these long years on with a linkage to Hobbes and that philosopher’s dark view of the perpetual conflict and ugliness of human life.

Saul Alinsky’s concepts of progress and power and their direct relation to threat is contrary to American views of how progress within the constitutional democratic experiment occurs. We have parties, and debate, discourse, discussions, and an open society that is meant to provide the environment in which people operating within the constraints of the constitution and the institutions that support it, and often motivated by ethical and moral concepts that were formerly universally held, can improve the experiment, improve the lives of themselves and their fellow citizens, and solve problems and challenges.

Such an experiment, built upon stability and reverence for institutions, is not as speedily reactive as those who agitate for rapid shifts and changes generally prefer. This seemingly ponderous nature of the institutions is seen by many today as a failure of the institutions. Thus, there is always a conflict, built in to the system itself, between desires for change and improvement all while sustaining the sometimes-slow moving institutions themselves that provide an environment of freedom and safety in which those changes can occur. This sort of American systemic change, essential to American democracy, too time consuming and complex for many, is rejected by Alinsky.

The denial of decent, charitable, ethical motivations is neatly summed up by Alinsky in this way: “people only do the right things for the wrong reasons” (at 22:38). This suggests that no change is motivated by care or charity or ethically/morally-driven concepts of right and wrong, and that the only changes that can occur are those that are forced upon people.

Alinsky believes that history and human development is a “relay race of revolutions” but the end point, the conclusion of all of these revolutionary races, is never quite identified. While Alinsky’s hyperbolic language suggests that this cycle of nightmares is supposed to be both beneficial and perpetual, some have postulated about what an end might be to such a grotesque cycle. Some have suggested that some form of socialism or communism is the desired end result for Alinsky, although he denied being a Communist; but it is the difficulties and challenges of a free political life, a free and open society, and open markets and competition that are at the heart of his complaints. The implication is that some uber-entity, in this case “the government,” would mandate solutions thus working swiftly and avoiding the delay and ugliness of debate and compromise.

It is the inequities of existence, a universal truth, against which the pragmatic decent and the fallen utopian always rebel. The great difference of course is that the utopians will not wait, and justify whatever means are required to reach the end point, while the decent retain their moral and ethical core and are prevented from excess by those same moral and ethical codes. In this upside-down worldview of Alinsky, the end point is never to be reached apparently, and the goal is simply conflict, revolution, upheaval, and pressure in perpetuity. Such are the foundations of dystopia built with a façade of advancement and benefit by utopians of the left.

Socialism, communism, and all sorts of utopian schemes are so popular, then as now, because they purport to solve these seemingly impossible problems. It is in the idea of the perfectibility of humanity that the utopian operates most vigorously; humanity is perfectible, impossible problems of existence are solvable, systems of great power yet benevolent central control can be constructed to facilitate these things, too. All of these challenges can be met and all solutions are within our reach if we should but act and brook no delay!

Concomitantly, those who oppose resolving the central problems of humanity can only be seen as “evil.” In this way, the opposition is properly demonized, all functional discourse and the flow of ideas are halted, and the utopian program, in this case perpetual conflict (at every level), is pressed forward by well-meaning followers who are deluded into believing that through the breaking of institutions and the fall of cities, states, and countries, the vexing problems of human existence can be resolved.

Open societies and open markets always mean that some will be more successful than others, that some will have more than others, and that some, unfortunately, will have to struggle harder than most to attain what they desire or need. Such things exist within every political system and every society that has ever existed as these are truths of humanity despite the fantasies of utopians—we are not all equal in ability, desire, capability, discipline, wisdom, wealth, etc. Any society constructed on such falsehoods will fall.

Relieving the inequities of life and of any political system are at the heart of most desires for positive change. That Americans would be motivated to reduce poverty as much as is possible, for example, is a laudable goal motivated entirely by concern for one’s fellow citizen in addition to the health and welfare of the entire body politic. Such a combination of prudence and compassion is inherent in the American national character—entirely denied in the Alinsky worldview.

What is a person who believes that any establishment is inherently an obstruction to the advancement of humanity and must be eliminated and replaced by some new establishment (whatever it might be) so that humanity can advance? And that such creation and destruction of institutions should continue ad infinitum? This is a philosophy of endless revolution and change (for its own sake) and the embodiment of the opposition to stability and government of laws and institutions. Where in chaos then do the people find comfort, resolutions to problems, equity, equality, fairness, safety, and compassion? The answer is clear: they do not.

What other than institutions and laws are at the center of an “establishment?” There is a corollary foundational pillar to this American edifice now under constant pressure and assault from the confused left—that is the support and respect for these institutions in the hearts and minds of the people. Fellow leftist travelers in the government, entertainment, education, and the media carry on this assault against the hearts of the people every day and night. These are the soldiers of perpetual destruction thinking all the while that they are the true patriots. It is a world turned upside down, and compliant with Mr. Alinsky’s stated purposes, but on a much grander scale: “The despair is there; now it’s up to us to go in and rub raw the sores of discontent, galvanize them for radical social change.”

There’s a saying that the devil’s great accomplishment was that he convinced people that he didn’t exist. A similar situation is at work on the American left, whereby revolutionary leaders convinced themselves and their followers that they aren’t revolutionists at all, but rather patriots who wish to uphold the institutions and the stability of the country by undermining those very things. There could not be a more confused and destructive political platform for an American political party as this one. The irrationality of these views—imbued by often thoughtful motivations of the desire to “help people”—is self-evident.

At the center of the Alinsky worldview is a rejection of the spiritual elements of humanity in favor of a strictly materialist perspective; this is a communist viewpoint that is out of line with American values and standards. Around the Marxist elements at the center is a rejection of the constitutional and institutional foundations of the republic in favor of perpetual conflict and thus, in their view, human advancement. That this endless pressure on the open society and the institutions that support it undermines the very system for which those on the American left claim to patriotically revere is an idea that appears not to have been given much consideration.

That this issue of constant pressure against any and all institutions and “establishments”—whatever they might be—is a matter of humanity-wide concern and not limited only to American considerations makes the Alinsky view and the current American leftist approach a utopian one. That is, they believe that their struggles are for the benefit of humanity, and not just the Democrat party or the American people.

The United States is no utopia and the pragmatists of the founding generation accepted, as do all reasonable people ever since, that there is no utopia. They accepted that the life of a man or woman does not necessarily have to be mean, brutish, and short and that a way other than monarchy and tyranny could take us there. They created a structure and a government, based on ancient models, that elevated the individual above the state. Sustaining such a world view and a government constructed upon it is a never-ending challenge from opposition mainly from without, but also from within. The elevation of the individual is the foundation of the country; it is a system wisely constructed on pragmatism and realism, and is not at all utopian.

Such it is that Saul Alinsky opposed then and his current acolytes in the American left and beyond now oppose in the same confused tradition of the reverence of conflict, strife, and deconstructionist, absurd perpetual revolution instead of the challenging, difficult, and laudable elevation of the individual over the state protected and supported by constitution and institutions.

In matters of utopian solutions in which there are those who stand in opposition to them, it is easy to see why the supporters of utopianism would view those who do not share their beliefs with derision and hatred. What kind of person could possibly oppose the advancement of humanity other than an evil person, a misanthrope? This was an essential lesson of the French Revolution—where decent people with decent motivations went off the rails, pressured and corrupted by the mob, then finally themselves becoming the mob, and committed wholesale barbarisms to ensure the success of their purported revolution for freedom and equality. Barbarism is no element of democratic freedoms (as noted by John Adams and Edmund Burke) neither is it but an unfortunate marker on the path to such goals of political freedom and individual rights (as suggested by Jefferson at the time). When the freedom revolution turns to barbarism, it is no longer a freedom revolution at all, but something quite the opposite.

What of those who believe that they are patriots while they undermine the institutions and the state that protects them and their freedoms? The #walkaway movement is a perfect illustration of what happens when those in such a movement see the truth—they walk away. As thousands have already professed to walking away from the Democrat party they aren’t all walking toward the Republican party. As of June, 2018, the #walkaway movement had over 100,000 members on their Facebook page. They tend to sustain a general classic form of American liberalism, uncorrupted by utopianism, globalism, and bizarre theories of human evolution. Such a massive shift is how old political parties die, and new ones are born.

In a televised interview on October 9th, Mrs. Clinton, the defeated Democrat candidate for president in the 2016 election declared that “You cannot be civil with a political party that wants to destroy what you stand for. That’s why I believe, if we are fortunate enough to win back the House and/or the Senate, that’s when civility can start again. But until then, the only thing Republicans seem to recognize and respect is strength.” Such a statement from one of the leading politicians in an American political party, made in an environment of political discord and almost unprecedented divisions and in which Representative Steve Scalise was recently shot and almost murdered by a radical leftist seems the height of irresponsibility. Such calls for incivility challenge the foundations of American political life and degrade the legitimacy and operations of the institutions and the government. Its potential for catastrophic consequences in our American political and cultural life need not be described.

Similar calls for incivility and worse came months before from Maxine Waters, a Democrat member of Congress, and went widely noticed but unpunished by the Congress itself. Such rhetoric that suggests harassment and violence are acceptable in American political life should result in at least a Congressional censure if not expulsion. That nothing was done at all by the Congress in response to Miss Waters’ outrageous and dangerous rhetoric is a catastrophic failure on the part of Congress to sustain American norms and censure and remove those who will not uphold them. Such a failure by the Congress to protect itself and the officials of the government cannot stand and sets a dangerous precedent of ignoring direct threats to institutions and individuals. The Congress must act in such situations, as protecting itself and our democracy are essential elements of its mandate.

What then does a follower of Alinsky do when she is denied the ability to “take power?” Mr. Alinsky put it like this, “I’m defining power as the ability to act . . . people do not get power except when they take it, or when they’re strong enough so that the other side gives it up” (10:06). The followers of Mrs. Clinton, of Mr. Obama, and of Mr. Alinsky were denied their opportunity to “take” power when Mrs. Clinton was defeated essentially by the mechanisms of the democracy to protect itself from the mob (checks and balances via the Electoral College).

Mrs. Clinton’s recent extraordinary call for incivility is an assertion that, in her view, the opposition is a hated, disrespected entity/group/thing and that, now out of power, the liberal/revolutionists will use “other means” to get what they want, whatever it might be. After all, according to Alinsky, the only power that can be had is the power that is “taken.”

These are not times of political strife and disagreements about policies and elections. Rather, these are times of deep philosophical disagreement. Mr. Alinsky asserted to Mr. Buckley that “in the field of action you’re compelled to polarize” (at 24:30). Could there be anything more polarizing than Mrs. Clinton calling for incivility instead of its opposite? Civility is the foundation of the courtroom, as it is a pillar of the American open society with groups of differing views all unified under shared beliefs about the constitution, and concepts of citizen and citizenship. Such is no longer the case.

There are those who consider American politics to be about political parties working within an accepted system/framework that is both of great value and that functions (though not as fast as some might prefer). There are unstated assumptions and assertions on both sides that drive belief and heartfelt action and that keep these political tribes/communities/movements/parties intact. After the defeat of Mrs. Clinton and this recent call for incivility from the apparent leader of the American left, the true nature of American politics is now clear.

Lincoln’s 1858 warning is most appropriate here: a house divided against itself cannot stand. Only by exposing the origins and philosophical foundations of leftist agitation, bitterness, and intolerance, and understanding the current political environment as a philosophical conflict instead of a standard matter of Democrat and Republican can we then take steps to improve things. If we don’t understand our open society and what happens within it and also work to uphold it, then we cannot find solutions. Only with the study of history can the path to a resolution be found.

__________________________________

Daniel Mallock is a historian of the Founding generation and of the Civil War and is the author of The New York Times Bestseller, Agony and Eloquence: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and a World of Revolution. He is a Contributing Editor at New English Review.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast