by Geoffrey Clarfield (June 2023)

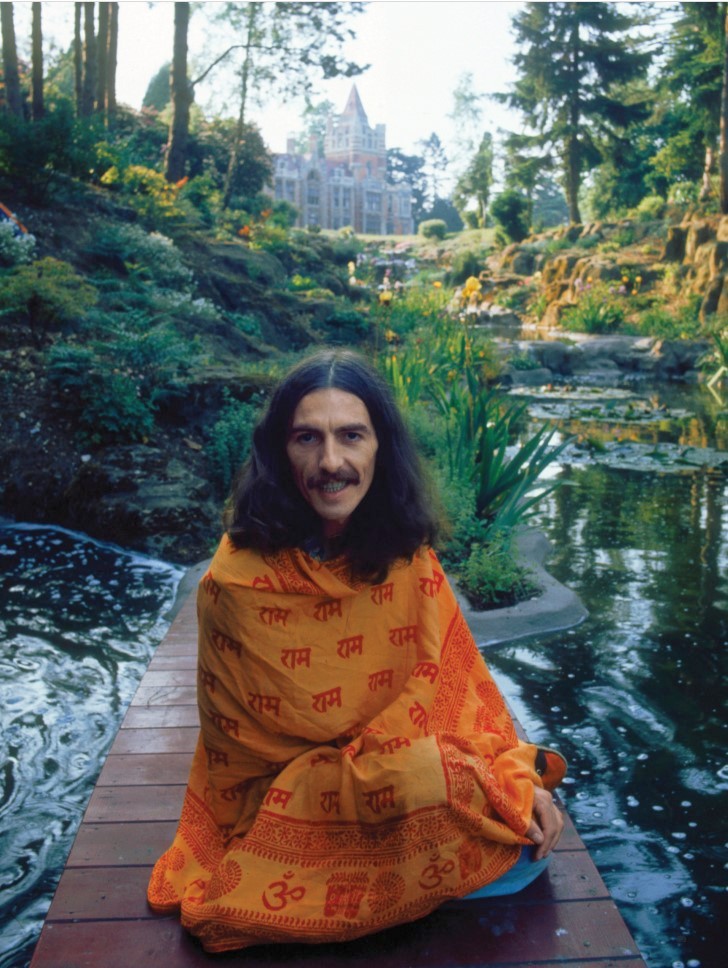

George at Friar Park, 1975

Here comes the sun, doo doo doo doo, here comes the sun

And I say it’s all right —George Harrison, 1969

I was on loan. John had sent me back to London for the winter. He was hanging out in New York more and more and the Beatles were not touring. Yes, I was the guy who was the Beatles and then John’s roadie until his murder. The Beatles were having “problems.” They had not split up, but they were spending more time apart.

John had worked out an amicable arrangement with George that I help him in his garden one winter. George welcomed me because I still did 20 minutes of daily transcendental meditation at the start of each working day, from the time we were in India together with the Maharishi. My salary would stay the same and my wife and kids were a half hour commute with a car which George had lent me for the winter.

The boys (I called them that as I was at least five years older than all of them) had soured on the Maharishi after he had put his hand on the thighs of a couple of their girlfriends, or perhaps a little more than that, during a closed eyed, group meditation session. John had famously called it the “group grope that sent the group back to London,” and he had told me that, in the end, it was all for the better.

George was living in a rented house on the outskirts of London. When I arrived, he gave me a tour of the garden—an Alice in Wonderland Victorian fantasy in rock, tree, and flower designed by a wealthy Brit in the mid-1850s, beside a massive farm house where George now lived and worked on his own music. The Beatles were still together but barely so.

I had to learn the all and everything about peachleaf, bellflower, cottage pinks, delphinium, hardy geranium, holly hock, Japanese anemone, lady’s mantle, lavender, peony, phlox, primrose and roses. Eventually George bought an even bigger house and garden at Friar Park many years later, when he was no longer a Beatle.

I had to take care of the garden during that winter. It was many hours of work and took me outdoors for a good six hours a day. I did not mind it as it was a good break from logistics and making sure amps and mikes were working in a studio or sound stage. At the end of the day, I would sit outside with George. I would sip a warm glass of Ethiopian mead, Tej, as they call it, and he would enjoy a slow puff on a joint.

I told George that as a lad I used to spend the summers in rural Northern Island. I came to love the dialect. I know it is not the popular Irish one, but it is unique and beautiful in its own way. As I never went to university and am a bit of an autodidact, I always imagined what Shakespeare would have sounded like recited in a Northern Irish lilt. Then I found out about OP or original pronunciation. Linguistic scholars had finally figured out what Shakespeare sounded like, that is the dialect he spoke and it was a lot like Northern Irish as spoken in a pub.

I had been working on reciting some of the sonnets in OP and one afternoon I recited one for George.

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date;

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm’d;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm’d;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st;

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st:

—So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

—So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

If you hear OP, it is as if the voice comes from the stomach, not the throat. It is manly and sandy, if I can use the term, and it does not have that effeminate Royal Shakespearian feel where the actors seem to be speaking from their throat. Instead, it is earthy and sexy. The kind of language the Beatles speak.

Every time we met at the end of the day, George asked me to recite it and then we would do it together. Afterwards he would get quiet and once he said, “People think we’re as good as Shakespeare. I sincerely doubt it. I feel like a street poet after I read anything he wrote. You know, like one of those Broadside Balladeers from 18th century London. I am not sure I am even on that level. It is both inspiring and demoralizing. But this Sonnet 18 should really be the gardeners’ credo!”

We turned it in to a kind of mantra and repeated it together in the thick Irish like brogue of Old Pronunciation at the end of each day under the gazebo, rain or shine, sun or clouds.

I didn’t see George for a while and, instead of Sonnet 18, I began to recite a different poem by Shakespeare at the end of my grey winter working days. I was lamenting winter and longed for the sun.

When icicles hang by the wall

And Dick the shepherd blows his nail

And Tom bears logs into the hall,

And milk comes frozen home in pail,

When Blood is nipped and ways be foul,

Then nightly sings the staring owl,

Tu-who;

Tu-whit, tu-who: a merry note,

While greasy Joan doth keel the pot.

When all aloud the wind doth blow,

And coughing drowns the parson’s saw,

And birds sit brooding in the snow,

And Marian’s nose looks red and raw

When roasted crabs hiss in the bowl,

Then nightly sings the staring owl,

Tu-who;

Tu-whit, tu-who: a merry note,

While greasy Joan doth keel the pot

It was a better reflection of my own mood at the time. I was having difficulties with my wife. We were not on a collision course but she spent more time taking care of her sick parents than with our own children. I did not fault her for that but it was hard for all of us. So my kids would sometimes join me for a day of gardening. And they liked meeting George. He took an interest in them, especially in what they listened to. They told him they liked the Beach Boys and dreamed of living one day in California, surfing USA. I was writing my own songs at the time but felt that I could not hold a candle to the Beatles who were my generous employers.

It has been an amazing run so far. Starting off by teaching a young John Lennon early rock classics, becoming their roadie, riding the tide of Beatlemania, getting a salary better than anything I could imagine for being around these fabulously creative young men, taking my wife and kids to their UK concerts. Having them sign my kids’ albums. All of this made me quite happy and the fact that their songs inspired my own. I had never shared my own with any of the four. And so, there I was alone each day at George’s house tending the garden during the winter of 69.

I had time to read about gardening and came upon this remarkable passage written by Francis Bacon centuries earlier. It became my inspiration and I copied out this section and kept it with me at all times:

God Almighty planted a garden. And indeed it is the purest of human pleasures. It is the greatest refreshment to the spirits of man; without which, buildings and palaces are but gross handiworks; and a man shall ever see, that when ages grow to civility and elegancy, men come to build stately sooner than to garden finely; as if gardening were the greater perfection. I do hold it, in the royal ordering of gardens, there ought to be gardens, for all the months in the year; in which severally things of beauty may be then in season. For December, and January, and the latter part of November, you must take such things as are green all winter: holly; ivy; bays; juniper; cypress-trees; yew; pine-apple-trees; fir-trees; rosemary; lavender; periwinkle, the white, the purple, and the blue; germander; flags; orange-trees; lemon-trees; and myrtles, if they be stoved; and sweet marjoram, warm set. There followeth, for the latter part of January and February, the mezereon-tree, which then blossoms; crocus vernus, both the yellow and the grey; primroses; anemones; the early tulippa; hyacinthus orientalis; chamairis; fritellaria. For March, there come violets, specially the single blue, which are the earliest; the yellow daffodil; the daisy; the almond-tree in blossom; the peach-tree in blossom; the cornelian-tree in blossom; sweet-briar. In April follow the double white violet; the wallflower; the stock-gilliflower; the cowslip; flower-delices, and lilies of all natures; rosemary-flowers; the tulippa; the double peony; the pale daffodil; the French honeysuckle; the cherry-tree in blossom; the damson and plum-trees in blossom; the white thorn in leaf; the lilac-tree. In May and June come pinks of all sorts, specially the blushpink; roses of all kinds, except the musk, which comes later; honeysuckles; strawberries; bugloss; columbine; the French marigold, flos Africanus; cherry-tree in fruit; ribes; figs in fruit; rasps; vineflowers; lavender in flowers; the sweet satyrian, with the white flower; herba muscaria; lilium convallium; the apple-tree in blossom. In July come gilliflowers of all varieties; musk-roses; the lime-tree in blossom; early pears and plums in fruit; jennetings, codlins. In August come plums of all sorts in fruit; pears; apricocks; berberries; filberds; musk-melons; monks-hoods, of all colors. In September come grapes; apples; poppies of all colors; peaches; melocotones; nectarines; cornelians; wardens; quinces. In October and the beginning of November come services; medlars; bullaces; roses cut or removed to come late; hollyhocks; and such like. These particulars are for the climate of London; but my meaning is perceived, that you may have ver perpetuum, as the place affords.

One day I brought my guitar to work, an old vintage Martin D-28 from the sixties with a Brazilian rosewood back, whose strings sound like church bells. At the end of the day, I was seated under the covered and heated rock garden gazebo singing Paul’s classic A World Without Love that had been made a hit by Peter and Gordon. All of a sudden a new melody came into my head. I had never heard it before and it took me a while to realize it was my own.

I tried to picture what George’s life in London had become for I was on the edge of it and not the center.

I remembered what the Beatles experienced when they came to New York and wrote the following verse.

Well they said the fair was everywhere

When the crowds were at your feet

I called a horse and cabby to Times Square

And you came and took a seat.

Then it became instantly clear to me that what made the Beatles different than, let us say the Rolling Stones, was their sincere search for love. This did not mean that they ignored the attractions of every woman who threw herself their way but, I had noticed that they were searching for happiness, each one in his own way and so I wrote this:

To be the one who loved the best

And be more certain than the rest

If in winter you were sore

Then in spring I love you more.

Thinking of Shakespeare’s sonnet it hit me that one day we will all be dead. The Beatles will be a memory. I will be gone. They will be gone and a wave of sadness came over me. And so I wrote:

When my grave is broken up again

It will be a shocking sight

Take my clothes and make the best of it

Take me out to dance at night

I varied the chorus with this verse:

For all the girls who made me smart

There’s still a place inside my heart

If in winter you were sore

Then in spring I love you more

Finally, being fed up with winter and hoping for the spring, I penned the following two verses.

Feeble ashes feeble breath

Is to think of love and death

Feeble hearts that do not grieve

Stand as still as autumn leaves.

Winter comes and winter goes

The mark of Cain in flash of snow

Woe is great and woe is mean

Give me your heart, don’t make a scene.

I sang it a few times and then recited it as a poem in Old Pronunciation at the end of the day.

When George came back from Scotland and we got back into our old routine, I recited my new lyric to him in OP as a poem. He really liked it but said, “It cannot be the bard. There were no Times Square in Elizabethan times.” I told him I had written it and that it has a melody. I sang it to him and the next day he brought his guitar to the Gazebo. He was playing a Gibson Humming Bird and its many colours blended splendidly with the flowers in the garden. One almost flowed into the other visually. Together we worked out an arrangement and he was open to most, if not all, of my musical suggestions. He said the song had “potential.”

I am not sure what he meant by that but that was a pretty fine compliment from one of the fab four. George was always the most tolerant member of the band, being the youngest and all and open to a Hindu world view. He hated negativity and that is one of the reasons he finally split from Paul, John and Ringo.

A week later he was gone again. When he came back he was in a spectacular mood. He told me, “I thought about the Bard and your sad and wistful song about winter. It possessed my soul for a while. I really liked it and could not get it out of my head. When I went up to visit Eric Clapton at his house, I played it for him and he liked it. I told him I was depressed and told him that it had been a long, cold winter. He laughed and together we went out into the garden and chanted, “Sun Sun Sun Here We Come” in original pronunciation, like Shakespeare. Eric nearly died laughing. “

George paused and took a drag out of his joint and then said, “I then took out my guitar and wrote the song. Eric wanted me to call it Winter Sun but I call it Here Comes the Sun. If John or Paul ask me to change the title, or even George Martin, I am going on a hunger strike. I wanted to thank you for the inspiration. It was somehow triggered by your piece and all our eccentric Shakespearian chanting. Now let’s go in the studio and record your song.”

That was back in the winter of 1969. George is no longer alive and I often miss him. It is now 2009 and I keep a digital copy of the recording on my web site. Anyone can listen to it. George played guitar and I sang. We did not sing it in old pronunciation.

For all the girls who made me smart

There’s still a place inside my heart

If in winter you were sore

Then in spring I love you more.

Table of Contents

Geoffrey Clarfield is an anthropologist at large. For twenty years he lived in, worked among and explored the cultures and societies of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. As a development anthropologist he has worked for the following clients: the UN, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Norwegian, Canadian, Italian, Swiss and Kenyan governments as well international NGOs. His essays largely focus on the translation of cultures.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link