Wonder Bread

by Larry Gaffney (June 2023)

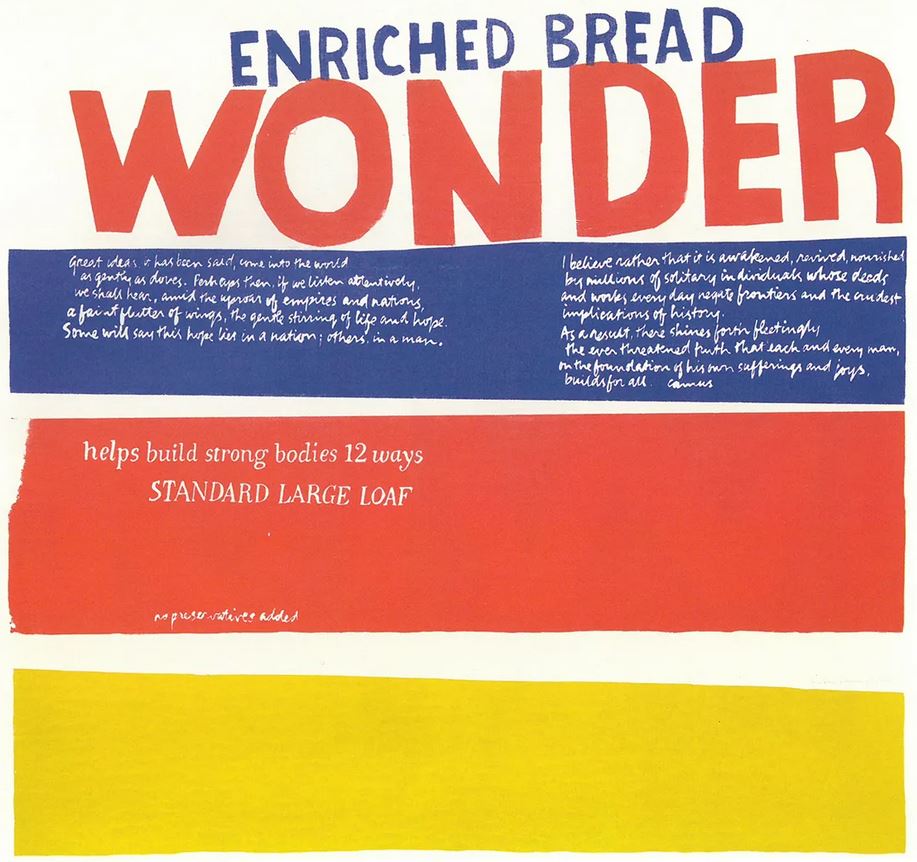

Enriched Bread, Corita Kent, 1965

If you seek a fitting symbol for Boomer childhoods, look no further than a loaf of Wonder Bread. Geezers will recall the packaging—white with red lettering, and a splatter of colored balloon-like circles. Why balloons? The baking company’s branding executive, stuck for a name, chanced to attend a hot air balloon race at the Indianapolis Speedway, was filled with wonder by the sight, and came up with the name and the packaging design on the spot. Also printed on the plastic wrapper was the dubious slogan, “Builds Strong Bodies 12 Ways,” 12 being the number of vitamins and minerals supposedly jam-packed into every loaf. Seriously? For a snack, my friends and I would grab a slice, tear off the crusts, stuff it into our mouths, and chew until the bread became a lump of semi-hard paste. No twelvefold surge of strength and vigor ensued from the process. I imagine that kids today have a rather different experience with quinoa bread.

I grew up in a white bread world, in a mostly Slavic section of Binghamton, NY, and we had no neighbors of color. There were seldom any African Americans on the TV shows I watched. There was one black student in the elementary school I attended, and only a handful in my high school. I had no meaningful relationships with black people until 1968, during the summer of my freshman year in college, when I found a temporary job in a factory. On the first day of work I ate my sack lunch seated at a cafeteria table next to Michael, a black guy my own age. We were both outcasts: Michael because of his skin color, me because my long hair and tie-dyed T-shirt marked me as a hippie among a redneck workforce. We hit it off immediately. Michael offered me one of the homemade brownies his mother had packed in his lunch. His copy of On the Road lay flat on the table. I pulled The Dharma Bums out of my backpack and held it aloft, and our friendship was off to a good start.

Michael Phillips was tall and slender, wore gold wire-rimmed glasses, and had a neatly trimmed afro. He was an English major at Harpur College, and although soft-spoken and wry of humor, attended most of the sit-ins and be-ins and other revolutionary events on the campus. He was not one to raise his fist in the air and yell “Power to the people!” but he was committed in his own quiet way to societal change.

We worked together only for the months of May and June. In July I was slated to start a job as a counselor at a sports camp in Pennsylvania. I asked Michael if he might consider joining me there, but he explained that he had no interest in sports, and was planning to hitch-hike across the country in August. It wouldn’t have worked out in any case. When I arrived at the camp I learned that the only black people there worked in the kitchen. In fact, the entire kitchen staff was black. Their specialty was fried chicken. This was an uncomfortable situation for me and a few other counselors who looked forward to the revolution and hated being served like massahs by black folk. Fortunately that was the final year of this plantation set-up. The staff, all of whom came from a small town in Georgia, grew socially enlightened during the winter and did not return, forcing the camp to hire poor whites from the nearby hills and dales. I worked there for the following two years, and will affirm that the quality of the fried chicken declined significantly.

Michael invited me to his house for dinner once, and I was stunned by the beauty of his sweet-natured sister. That she was only sixteen struck me as irrelevant. At the table I kept my feelings hidden while imagining unlikely scenarios of illicit romance. Michael’s parents were amiable enough, but Mr. Phillips, who was not slender like his son but had the build of a pro wrestler, gave me a hard look while I was in the middle of some flirtatious banter with young Evelyn, and I shifted my full attention to the roast beef on my plate.

This mountain of a man showed up at the factory one memorable day as our crew gathered in the locker room after work. Michael—and the two other young black men employed there—had been put in some dicey situations with heavy machinery, and their complaints were laughed at by the racist foreman and his cohorts. Tom Phillips stood for a moment in the doorway while the much smaller white fellows gaped at him. Then he casually took hold of the nearest locker—a massive unit almost seven-feet tall—dragged it across the floor, and blocked the doorway with it. Nobody was leaving. In a quiet but firm voice, he said, “If my son has any more trouble here I will come back, and we will sort this out man-to-man.” He glanced at the other two boys and continued. “And remember, I have three sons.” He pushed the locker back to its original location, allowed his baleful stare to make a circuit of the room, and left without another word.

There was some snorting and dismissive low talk among the crew. But the three workers of color were not further abused. Once in a while they were spoken of as “my three sons,” but with a tone of grudging respect.

Before leaving for camp I returned the favor and invited Michael to my home. My parents appreciated his good manners and obvious intelligence and said he was welcome any time. But sour-faced looks by a couple of our neighbors who saw him come and go on that day caused him discomfort, and he chose not to return.

Once my father asked me if Michael had a girlfriend. I thought it over for a moment and said, “Not that I know of. Why?”

“No reason,” said my father, changing the subject.

On a weekend during the fall semester, Harpur College had a festival to celebrate the intersection of student life with culture and the arts. There were rock bands, and poetry readings, and a couple of minor celebrities who spoke of their adventures in the psychedelic realm. There was also a screening of King Kong that Michael and I attended with some friends. We looked forward to the film—projected on the big screen of the campus theater—as sheer entertainment. But it soon became clear that this event would have sociological implications as well. The front rows were occupied by members of the college’s black power movement. A lively and raucous group, they shouted insults at the white men who subjugated the giant gorilla for capitalist exploitation. Since we in the audience were anti-colonialist hippies and activists, none of us minded that these shouts interrupted the dialogue, and in fact we added our own outraged voices to the tumult. At the film’s end, as Kong clutched his bullet-ridden chest, gently placed Fay Wray at the top of the Empire State Building, and fell to his death, a black kid bolted from his seat in the front row and rushed up the aisle. His face stricken with grief, he cried, “They got my man!” Several people who heard him broke into applause.

King Kong deserves its reputation as a classic. Yes, the acting and the dialogue are dated, but the story is dramatic and moving, with the mythic power of interlaced themes that pulse with cultural and anthropological verities. As we stood around afterwards discussing the film, an acquaintance emerged from the theater, saw Michael, and said, “It’s true! They got your man!”

For an awkward moment none of us spoke. The grinning interloper waited for an appreciative reply. But he didn’t know Michael well, didn’t understand that he was a rather private person who never would have drawn attention to himself like the kid who charged up the aisle.

In a manner not unkindly, Michael said, “Contrary to your expectations, I do not identify with apes.”

Eventually Michael took the cross-country trip, but not as a hitch-hiker. His parents bought him a car so he could safely make the journey that they were unable to prevent.

One morning he packed his few possessions and drove away without telling anyone. I never heard from him—not even a postcard. He did not return to Harpur College. I saw his mother at the grocery store and asked what had become of him. She was evasive, said he had met some people and settled into a new life in Los Angeles. He was going to college there. At that moment Tom Phillips came around the corner of the aisle with a jumbo bag of pretzels. He seemed displeased by my presence. I muttered a goodbye and moved on.

Years later I ran into someone Michael and I had hung out with during the revolution, and was told what I should have been able to figure out on my own. “Didn’t you know?” she asked. “He was totally gay. His parents found out and were crushed. I don’t think they ever forgave him. Last I heard he was teaching at a junior college in California.”

I asked about Evelyn.

The woman shrugged. “No idea. I was never close with her. I think she left town, too.”

More years went by. One day, brooding over nostalgia, I suddenly thought of Michael and looked him up on Facebook. He had a bare-bones profile without a photo or much identifying information. I sent him an instant message. Do you remember me? I asked.

Of course I remember you! he typed. He gave me a number to call.

His voice was unchanged—dry, and gently mocking. I said I was sorry we’d lost touch all these years.

“So am I,” he said, “but it had nothing to do with you. I cut myself off from everybody. It was a hard time. Especially for my parents. We didn’t communicate for years.”

“And now?” I asked.

“Hang on a sec,” he said. “I’m sending you a photo.”

I clicked it open. “Wow,” I said. “Look at those smiles.”

“Crazy, isn’t it? They got over the adoption thing right away. Nothing better than having a grandkid to bounce on your knee. They’ve even accepted Franklin as my husband. That’s him standing next to the couch.”

“A good man?”

“The best.”

“So what’s your sister up to?” I asked.

He laughed. “Forget it. She’s still in Binghamton, but with a husband, and a daughter in high school.”

“Husband black?”

“As the ace of spades,” he said.

When I told this story to a much younger friend, she bristled at hearing “the ace of spades.”

“That’s racist,” she said.

“What are you talking about? Michael said it, not me.”

“That’s not the issue,” she said. “Those are hurtful words no matter who says them.”

Maybe she’s right, maybe she isn’t. What do I know? I was raised on Wonder Bread.

Table of Contents

Larry Gaffney is a tennis coach in Williamsport, PA. His book, Finding Nabokov: A Literary Companion, is forthcoming from McFarland.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast