Working Class Heroes—Populism Finis

by Robert Bruce (August 2020)

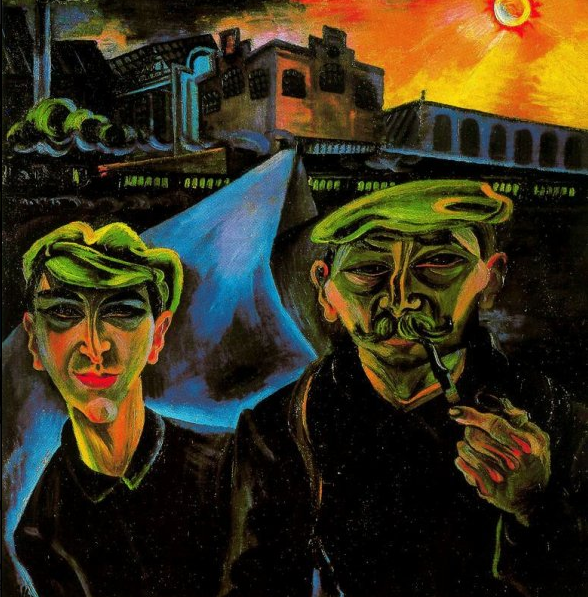

Leaving the Factory, Conrad Felixmüller, 1920s

Modern society wants all men to be free and equal, not only before the law, but in every respect. This is nonsensical, and primarily a tool used by those who want to become a new ruling class by toppling the established ruling class. It defies logic and common sense, creates envy and suspicion, and negates trust and loyalty. —Richard Weaver

To lie like this—telling stupid, boastful whoppers which can be definitively exposed for what they are—is a travesty of effective politics. Labour must save its big lies for when it really needs them. —Sion Simon

Having lived in neighbouring Whitley Bay as a youth, I know Blythe pretty well, and even the locals would be honest enough to admit it has seen better days. After the mine closed in the eighties, it lived off respectable working-class capital for a while but, by the nineties, it was already attracting notoriety as the drugs capital of the north east with rates of mental illness and heroin overdoses usually only encountered in the bleakest of Glasgow council estates. The cause was not difficult to locate. Bates Colliery had employed almost 2000 men at the height of the coal boom and, like most, towns built on 19th century industrial sinews, it was ill-prepared to embrace the brave new dawn of the service industry. Outside of tele sales, and a shrinking military industrial complex most of the jobs in the 90s were in the security industry and, when I did my stint as a guard on the Silverlink industrial estate, most of my co-workers were ex-miners from Blythe and Ashington, kitted out to a man in ill-fitting navy blue V necks and sporting cringeworthy logos which were in themselves potent symbols of their fall from grace. Carlyle was right to see all true labour as sacred and the Victorian ethic of hard work traded heavily on it, particularly when it ascended to the dignity of a craft. Miners could be buried alive right up until the sixties and take pride in their work in the industrial age. After the curtain fell on the workshop of the world the sleights to a proletarian’s worth came thick and fast, and Carlyle for one had never worked for Delta One Security. There are few better ways of humiliating a man for an honest day’s work than sewing the motto ‘You’ve tried the Rest, now try the Best’ onto a jumper tailored for a child, but anyone who had seen his father broken by the miners’ strike would have already seen worse, and these, let it be remembered, were the lucky ones. Working 70 or 80 hours a week in the dark at least put a decent veil on your lowly station and, with houses going for 12k a pop, you could at least get a mortgage and pray for better times. For my own part, a leisured half man with and I had no such worries and I at least entered the University of Life.

Pre-minimum wage, it nevertheless wasn’t that onerous as far as the toil went. My jumper fit and, in between bouts of half-hearted study, I spent most of the time standing sentinel for the feared mobile patrol supervisor ‘Hard Knuckles,’ a thuggish man on steroids who plotted tirelessly to catch men sleeping, and an ex-enforcer for one of the north-east’s pullulating horde of hard men. They got their sleep and, after inspecting me cautiously, spread wild rumours about an indigent sociologist from Durham University conducting ground-breaking social research on the underclass. It’s a common enough form of outdoor relief for third-rate academics these days and I took no offence at their cautious reserve, even after I found out they were speculating on scant evidence I was a ‘hucklebuck’ (I must revert to my sanitised middle class prejudices here and state for the record some of my best friends are gay, and I would be ‘proud’ if I had reason to be), and their comical attempts to keep a fitting decorum still provides a mental storehouse of comedy moments. I probably did sound posh and, in my stilted social interactions, even the ill reputed ‘hard knuckles’ felt pressured to play the part. Gasping for some small talk to break the tension during an unannounced visit (a kulak had informed on me for leaving the site early each morning), I quipped wittily that it was a bit chilly outside. He mulled his response and after a lengthy mental rehearsal confirmed that ‘the temperature had indeed dropped dramatically.’ All the air left the room, and the deafening silence lasted the whole hour it took him to gravely administer the written warning. As he exited into the night in search of other slackers, he solemnly warned me that ‘disattention and ignorance to company protocols would lead to severe disciplinary calamities’[1]. To this day, it is the most searing HR transgression I have committed and I’ve kept hold of the words lest fate should find them serviceable. Amidst the lethargic sleep-deprived guards on this nocturnal gulag, I was reborn a middle-class hero and, as for the treacherous stool pigeon who ratted, vengeance was swift. We collected the phone numbers in his salubrious office block and rang them on the hour with cruel intent. A prolific consumer of cheap white cider, the potbellied and sleep-deprived class traitor stumbled out in the morning to find his tyres slashed and (somewhat later, when he broke down in the Tyne tunnel) sugar in his tank. It was spiteful retribution but any remorse was wiped out by the legend we concocted that he was a convicted paedophile2] Justice was served and the conspiracy theories died down. I wouldn’t have got far anyway with the research.

As someone who lived his formative adolescence in the mean streets of Woking, my fieldwork skills were piss poor and I couldn’t get too far with the accents. Even to the earthy inhabitants of Newcastle the more remote Northumbrian dialects can be well-nigh incomprehensible and the losses in translation was a testament to how isolated these towns were. Blythe is the kind of picturesquely poor place progress tends to leave behind, and when the northern post-industrial renaissance came—a succession of out of town retail parks with minimum wage jobs and designer leisure wear that sucked the life out of shitholes like Gateshead and left the unemployed clad in barbarous Adidas technicolour—it didn’t even get a metro station. It is unusual historic destinies are entrusted to such unassuming towns, still less that they rise to the occasion and earn their place in history. On December 12, 2019, they did just that and voted in a Tory, even if they chose the Brexit Party as their murder weapon. It was big news, and when the shock descended on the metropolitan bubble the knives were soon out. Blythe is not working class in the way that, say Basildon is, and the instinctive response of the bohemian class was even more vicious than that they turned on the Tory lumpenproletariat of the eighties. The latter might at least be credited with the low virtue of self-interest, the poor had no such excuse and Paul Mason, the bewilderingly feted ex BBC economics correspondent wheeled out as the oracle on Labour’s proletarian deficit, was ready with his own dog whistles.

I’m done with people saying, ‘we can’t lose the working class.’ A Lithuanian nurse is working class, an Afghan taxi driver is working class. An ex-miner sitting in the pub calling migrants cockroaches has not only no added human capital above the people I just mentioned, but it’s also not the person we are interested in.

It was a bizarrely overstrung reaction and Mason’s favourite bogeymen must have been short in short supply in Blyth in any case. Its migrant population is barely big enough for even an obsessive to notice and in a part of the country where most people live streets away from where they were born, and a visit to an Asian newsagent is as close as they’ll get to a connection with the global village, it could only have made sense to someone festering in the polite bigotry of the metropole left. In the BBC, where most depictions of working-class voters could easily have been plucked from the ramblings of Gustav le Bon, these lazy caricatures come as easy as breathing and, after hopes of a Red Dawn crashed, the liberal broadsheets were pullulating with outrage.

A stampede of journalists soon descended upon this small Northumbrian market town to see the evil up close but, to their disappointment, their cornered prey struck an unexpectedly solemn and dignified note. Far from throwing up cockroach anecdotes these random samplings of vox populi produced thoughtful and troubled interviews, with even the most laconic of responses striking a more profound tone than their social betters usually do when wheeled out for their edifying soundbites on global warming. This is doubtless as it should be, all the locutionary advantages an expensive education can bring will not compete with the kind of eloquence you can summon when talking about a community you have deep ties in and, when you have to throw off deep ancestral habits to make a statement, the oratory is always likely to sound more impressive. They had skin in the game and, compared with the gormless Pavlovian soundbites of yuppies in Brighton or Clapham rolling off the usual roll call of racists taking their cue from bus logos, they all sounded like Pericles. Their votes took effort and they found the weight of words. As a vindication of the muscle tone of a coarsened plebiscitary democracy, it was priceless. They got little credit for it all the same, and more than their fair share of calumnies.

Blyth’s sin was not an original one. Essex car workers and racist dockers had disgraced themselves during the Thatcher years and New Labour were sanguine enough about the reliability of their workers credentials to hedge against this vanishing block vote. The first sign of changing fashion registered with the new found affection for the judiciary. The Labour Party had traditionally been distrustful of the courts, cutting them down to size after the infamous Osborn judgement provided its raison d’etre but after they absorbed all the modish trendiness of the counterculture, judges soon acquired new found respectability as a guarantor of genteel prejudices. All that was needed was a cult of the mob to mask the underlying condescension. A certain insincerity was the necessary price. Blair, lest it be forgotten, was once the supreme exponent of the populism he affects to despise and it fed off his own haughty class consciousness. Like most of the Labour-establishment, he was obsessed with the influence of the tabloids and needed no persuading that the Tories fed off the ignorance of teeming solitudes ready to leap on the agitated sensations of the moment. His solution was new and ever more vulgar instruments to keep the masses in their place and Alistair Campbell, the editor of Labour’s only friendly red top, was ever fertile in ideas for corrupting the public discourse. Lying was certainly one of them and during the wilderness years many Labour supporting journalists were willing to defend it. As Polly Toynbee noted during the 97 election:

Labour is taking no more risks. After four defeats, they have abandoned their view of the voter as a decent sort and adopted the Tory model of the voter as a selfish lying bastard. Soon after the last (1992) election, I talked to a deeply depressed shadow cabinet member who cursed voters bitterly and concluded; ‘the only way we can win is to lie and cheat about the taxes the way the Tories do’ Let us hope that is their secret strategy.

She needn’t have worried and they came in spades. Peter Oborne’s The Rise of Political Lying remains the best primer on the sheer scale of a dishonesty that was wretched in itself but its effects on the body politic were aggravated by that paranoid sensitivity to the public mood that all authoritarian regimes share[3]. This is what ‘choosing your lies wisely’ entails and they employed all the dismal science of public relations to pull it off. The penchant of New Labour for focus groups is by now legendary but it implied no slavish commitment to democratic principle. A desire to connect with voters is not the same thing as seeking a mandate from them and the sheer passivity of the experience was more appropriate to advertising than politics. Rousseau would have recognised their servile nature—however misinterpreted it has been, his distinction between the will of all (the sum of atomised preference) and the general will (a voice formed by communal deliberation), is a valuable distinction and it is worth bearing in mind when confronted by the evidence of Tony Blair’s views on them. Coming across findings that groups were not warming to the idea of John Prescott as his deputy leader, he instructed the messenger to ‘refocus his focus groups.’

As a commentary on the cynicism of it all it is priceless and anyone familiar with the Hawthorne effect, studied so diligently by industrial relations students in the seventies, will be familiar with the underlying logic. Give people the verisimilitude of ownership through conspicuous displays of empathy, and their identification with the institution is enhanced, irrespective of whether any substantive power was conceded. The methods are rarely savoury. Orwell tapped into it with his five minutes of Hate in 1984, and New Labour’s absurd moral panics over asylum seekers,[4] and paedophiles drip fed to the cartoonishly right wing Sun to stir up neutered rage was of a piece with this degenerate psychic masturbation. Blair only invoked the demos as a subliterate cypher he could attack his opponent with, and it is striking how feeble Boris Johnson’s transgressions look when compared with the orchestrated attack on judges that his press advisers unleashed during his time in office. Before 1997 this breach with convention was almost unthinkable but after his cloyingly infantile ode to the common man it was routine, and it found a vulgar mouthpiece in the yellow Murdoch press. As a template for soft fascism it was perfect, but it relied on the kind of docile minds that might overlook the fact that they had raised the spectre in the first place. In the final analysis, there weren’t enough of them and the old verities are out of fashion.

What is so sniffly derided as populism now is, for all the spilt milk of left wing journalists, nothing more than democracy and it is to the eternal credit of unenlightened working class voters that they saw through the circus of new Labour’s soiled version and decided to live dangerously. No one engineered Brexit or a Conservative landslide—whatever the wisdom of the choice, it was made against the grain of conventional wisdom and the weight of government propaganda bearing down on it. Nothing could be further removed from the Blairite populism that the likes of Polly Toynbee lauded in 97 and it was delivered with the mass turnouts political scientists thought were a thing of the past. All of this tells its own story. Democratisation and embourgeoisement used to be synonyms—today the middle classes, it should be noted, now have less favourable views on democracy than the working class and, to judge by the hysterical behaviour of today’s younger bohemians, this is something that will only deepen as the toxic masculinity runs dry. All this doubtless runs the risk of sounding like a Jeremiad on moral corruption but, when one understands the underlying sociology, it is easier to understand as a social phenomenon rooted in real social changes.

Amongst the manicured Europhiles of west Kensington, Theresa May’s dismissive rejection of citizens of the world went down as the shortest suicide note in history and it doubtless had an unfortunate historical resonance. But, in age where the rich have detached themselves from the most elemental obligations of citizenship, rootless cosmopolitans are a real problem nevertheless. The yelps of pain that drove the Tories out of affluent London emanated from streets where houses are left fallow half the year whilst people sleep on the street and, lest anyone be impressed by the affected vulgarity and demotic tastes of the new rich, it is worth noting it is precisely this coarsening of manners that has made this double standard easier. In modern times, slobbery is a bigger danger than snobbery and herein ultimately lies the importance of Blair’s modern man credentials. John Major wore a tie on a Sunday and exuded a stuffy old fogginess that made him never less than fifty years behind his times. Latching onto such unimposing targets particularly when you have privilege to hide (Major, it should be remembered, was the son of a circus performer and went to a bog standard Comprehensive. Blair, by contrast had a gilded youth and acquired all his contrived earthiness from Fettes, the Eton of the north) was easier than discarding your own silver spoon. Dress down like Zuckerberg and you can just be an ordinary millionaire. Spread the doublethink far enough and you have the lazy cult of New Labour with all its tawdry egalitarian icons.

The cult of Diana, coveting her self-indulgent martyrdom without letting go of her titles is an abject example of where this theatre of the meek went and in the worship of these little rich heroines we end up with the most dulling afflictions of false consciousness. She was, as George Walden noted, a pretty unaccomplished individual: minus her privilege, her academic achievements would have fitted her for a career on a supermarket check-out but to a certain brand of sickly spirited individual this canonized mediocrity and self-indulgence was the attraction.[5] She held no airs. She kept her money all the same and never needed to pay penance for her good fortune. She had unearned wealth in spades and even more unearned emotion. More than a few feeble minds bought the charade but a greater number realised it’s healthier in these situations to hold on to the class hatred than numb yourself to an insult. Working class people know the ‘compassion that wounds’ up close and personal and this is what real populism feels like. For a while it provided the perfect double standard for the low brow oligarchy he turned Britain into, but the reserves of cynicism required to keep it up are now gone and it is an impressive thing to see sanity restored by people who don’t have the luxury of getting it from a media studies degree.

[1] The English actually isn’t that bad. Anyone who has listened to the well fed public sector nomenklatura drivelling on about ‘impactive policies’ going forward, and starting sentences with so will know what I mean.

[2] I struggled myself to give a convincing justification, but my colleagues informed me that as he lived south of the Tyne, he was a Macam and hence indisputably a homosexual or, (there was to them at least ,evidently a continuum) a child molester.

[3] One of the counter-intuitive ironies of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union’s post war satellites was the sheer weight of effort devoted to finding out what people were thinking.

[4] With asylum seekers the distance between substance and reality is jarring. The emphasis on bogus asylum seekers was pointed but the solution was easy. They granted asylum at record rates. Thus, the bogus asylum seekers disappeared.

[5] They cannot pretend to be unfamiliar with the logic as it is rolled out often enough against Trump and his appeal to the down at heel.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

_____________________________________

Robert Bruce is a low ranking and over-credentialled functionary of the British welfare state.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast