Three Stories by Anne Dublin

by Norman Simms (March 2018)

Written on the Wind, Hodgepog Books, 2001. 82pp.

The Orphan Rescue, Second Story Press, 2010. 125pp.

44 Hours or Strike! Second Story Books, 2015. 136pp.

.jpg) y a happy chance, I recently made contact with a Jewish writer of children’s books in Toronto, Canada. She is currently writing about the Jewish children sent as slaves from Portugal in the late fifteenth century to the small island of São Tomé off the western coast of Africa. I had written a series of essays on the topic many years ago, and she asked a few questions. Because I have not kept up-to-date on the subject of children as slaves and Jews as forced colonists in the Spanish and Portuguese Empires, I couldn’t give her much new insight. Another point of contact in our lives was the interest in the ILGWU (International Ladies Garment Workers Union), as I had written short stories about one of the founders of the union and am proud of the fact that my great-uncle Abraham Rosenberg’s portrait was painted on banners in the Labour day parades in New York City, and even had a warship named after him in World War Two. Yet we did begin to exchange comments on our lives which, surprisingly, had a number of interesting cross-overs and almost being in the same place at the same time, and then about writing short stories. These connections led to sending each other some of our little books.

y a happy chance, I recently made contact with a Jewish writer of children’s books in Toronto, Canada. She is currently writing about the Jewish children sent as slaves from Portugal in the late fifteenth century to the small island of São Tomé off the western coast of Africa. I had written a series of essays on the topic many years ago, and she asked a few questions. Because I have not kept up-to-date on the subject of children as slaves and Jews as forced colonists in the Spanish and Portuguese Empires, I couldn’t give her much new insight. Another point of contact in our lives was the interest in the ILGWU (International Ladies Garment Workers Union), as I had written short stories about one of the founders of the union and am proud of the fact that my great-uncle Abraham Rosenberg’s portrait was painted on banners in the Labour day parades in New York City, and even had a warship named after him in World War Two. Yet we did begin to exchange comments on our lives which, surprisingly, had a number of interesting cross-overs and almost being in the same place at the same time, and then about writing short stories. These connections led to sending each other some of our little books.

Her books are written for small children and adolescents. This is not a field that I have kept up with. It has been a long time since my son and daughter were children and our one grandchild has grown and moved across the Tasman Sea, completed her university studies and married a likable young man. With no little ones at home to read to or adolescents to encourage to read, I have had no opportunity to look at these kinds of books for a very long time. My wife and I, however, have kept or purchased some in second-hand bookshops (for infrequent visitation by former students who have new families) and these are those titles we recall from those days of yore, including few books we recognized from our own childhood. These are what we consider “the classics” in the genre, most dating from the early half of the twentieth century. A cursory browsing of more modern little books over the past twenty or so years did not rouse any interest or enthusiasm.

So, it was with some trepidation that I received the packet of short books by Anne Dublin. Would these be namby-pamby and soppy stories that condescended to the supposedly dumbed-down new generations? My old man’s grumpiness in retirement was built on disappointment and frustration in the last years of university lecturing. The literate good students seemed to have disappeared in a cloud of politically-correct laziness and blank stares when any of the “older” authors were mentioned in class. It looked like civilization as we knew it was over. Could this proffered set of Canadian titles for young readers break through my curmudgeonly defences?

I am pleased to say that Anne Dublin’s books are anything but simplistic or namby-pamby, and that, while she does not stretch the limits of vocabulary or sentence-structure of what young people can be expected to handle, she doesn’t pull any punches in regard to her themes and characters. That is, each book is age specific without condescending to her readers, and indeed she introduced situations where the children will have to ask themselves questions or be involved in discussions with parents and teachers about real moral problems in these stories. The world they depict is not just or fair and, in fact, is often harsh and cruel. Children are told that it is not true that if you really want something and wish for it to happen, it will. Instead, they are shown that at best you have to be strong, grit your teeth, and try to survive, something not always guaranteed. Parents or other adults cannot—or will not—give children all they want and need. Authority figures can be weak, foolish or mean. Therefore, compromise, patience and resignation may be one’s best options. No matter how hard you try or think you can stand up to bullies and persecutors, it doesn’t always work. Children, Jews, females and minorities in general have a hard time in life. This will not go over very well in Hollywood or Disneyland.

Though Written in the Wind is supposed to be about one of the most the terrible storms to strike Toronto on 15 October 1954 (Hurricane Hazel), cursorily described in a historical note on page 77, the .jpg) focus of the book is on the narrator Sarah. Sarah and her twin brother Michael are the twin eight-year-old children of Jewish immigrants from Poland who managed to survive the Holocaust. That European catastrophe remains an almost never-spoken-of-event throughout the story, the son and daughter barely understanding what made their parents different from the Canadian families of the schoolmates and playfellows around them. Sarah and Michael are aware that their parents cannot speak English well, are having a hard time settling into Toronto life, and seem squeamish about the games and adventures their offspring enjoy.

focus of the book is on the narrator Sarah. Sarah and her twin brother Michael are the twin eight-year-old children of Jewish immigrants from Poland who managed to survive the Holocaust. That European catastrophe remains an almost never-spoken-of-event throughout the story, the son and daughter barely understanding what made their parents different from the Canadian families of the schoolmates and playfellows around them. Sarah and Michael are aware that their parents cannot speak English well, are having a hard time settling into Toronto life, and seem squeamish about the games and adventures their offspring enjoy.

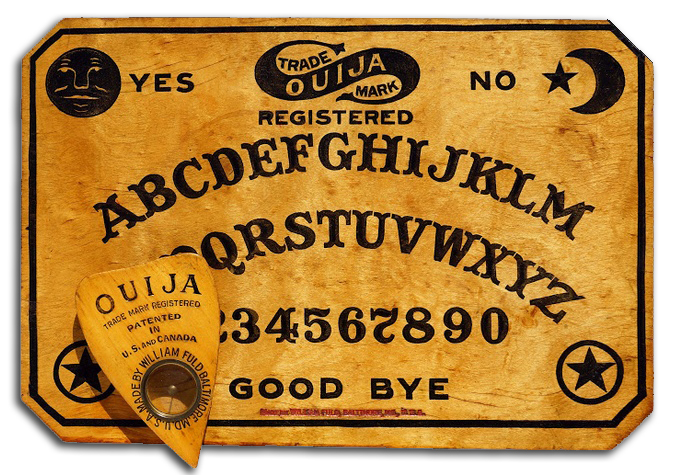

While Michael has a tendency to run off and play dangerously close to the railway tracks, Sarah seems obsessively to visit with Evelyn, the owner of a nearby grocery shop and, against her mother’s direct instructions, to stay late and help out in the store. There are many unanswered questions about Evelyn, such as why she is unmarried, why she comes to depend on an eight-year-old helper and, most significantly, why she is constantly consulting a Ouija board. Sarah’s mother senses something unhealthy in the relationship between her daughter and shopkeeper, a woman of her own age (forty), and the peculiarity of her need to ask the magical board to tell her about her immediate future, such as the financial status of her grocery. The child is, to be sure, too young to understand what might be bothering her own mother and why there is a fascinating attraction between herself and shopkeeper.

In some sort of a way, there are all sorts of things in Dublin’s little book that don’t quite match up and yet call for juxtaposition, comparison, and discussion. Just as Sarah and Michael are twins and yet not identical, their gender, height, personalities and sense of responsibility bounce off one another, enough so that the teachers in school decide it wisest to put them each in separate classes. What makes Evelyn different from Sarah’s mother is barely hinted at, one married, one not; one grown up safe from the European persecution of Jews, the other a survivor barely able to articulate herself in English or to speak of what happened to her; one insecure in her business and unsure of how to develop it, the other hopeful that her husband will be able to create better conditions for the family. The hurricane indicated in the title to the book which leads to eighty-three deaths and leaves five thousand homeless is strangely virtually absent from Sarah’s story until a few vague references in the final pages, so that it stands in some sort of perhaps symbolic relationship to the Shoah that caused her parents’ suffering and leaves them psychologically wounded in ways the little girl barely senses.

In some sort of a way, there are all sorts of things in Dublin’s little book that don’t quite match up and yet call for juxtaposition, comparison, and discussion. Just as Sarah and Michael are twins and yet not identical, their gender, height, personalities and sense of responsibility bounce off one another, enough so that the teachers in school decide it wisest to put them each in separate classes. What makes Evelyn different from Sarah’s mother is barely hinted at, one married, one not; one grown up safe from the European persecution of Jews, the other a survivor barely able to articulate herself in English or to speak of what happened to her; one insecure in her business and unsure of how to develop it, the other hopeful that her husband will be able to create better conditions for the family. The hurricane indicated in the title to the book which leads to eighty-three deaths and leaves five thousand homeless is strangely virtually absent from Sarah’s story until a few vague references in the final pages, so that it stands in some sort of perhaps symbolic relationship to the Shoah that caused her parents’ suffering and leaves them psychologically wounded in ways the little girl barely senses.

The back cover of this Hodgepog Book proclaims that it is meant for a reading level of Grades 5-6, that is, pupils about the age of Sarah and Michael. There seems an attempt on the final page of the narrative to soothe the fears and anxieties of the twins following the storm and in the aftermath of their parents’ extreme panic over the safety and health of the children occasioned by the storm, but to any adult reading the story there is far more to worry about, all of it at best implied in the words and mind of the eight-year-old narrator. A wise teacher might be able to guide classes into a discussion of why normal people who seem to have come through one of the most terrible experiences in human history looking happy and strong but are nevertheless profoundly wounded in their souls and extremely frightened by the world. The concerned parents who supervise their children’s readings might be able also to help their boys and girls see what is so troubling about Evelyn’s introduction of the Ouija board to Sarah, its grasping after irrational and mystical guidance in a world that has just come through the madness of Nazi madness and rage and which needs, above all, rationality and common sense. Other questions concerning sexual improprieties hinted at in Evelyn’s loneliness and need for a vulnerable and naïve child’s friendship could also be tactfully breached.

The Orphan Rescue also implies more than it tells in its narrative, though perhaps with less hiding of problematical issues than in the previous book, perhaps because it seems aimed at readers three or four years older than the twins Sarah and Michael. It is also told from a non-intrusive narrative voice, a voice that describes people, places and events, but leaves the themes implied in the speeches of the characters and some of their transcribed thoughts. Set in Sosnowiek, Poland in 1937, on the eve of World War Two and the Holocaust, its focus is on the painful conditions of poverty in which twelve year-old Miriam and her seven year-old brother David are caught. Both of their parents have died. They are taken in by their grandparents whose own age and inadequate incomes make life extremely difficult. When the grandfather injures his hand and is unable to carry on as a locksmith, the breaking point comes. Miriam, who dreams of becoming a teacher, is forced to leave school and work in a butcher shop, while little David has to be entered into a Jewish orphanage, thus separating him from his remaining family.

Nothing is spoken of concerning anti-Semitism or of the impending disasters of war and genocide. The bad things in the world appear as part of a world-wide Depression and are embodied in selfish, weak-minded and greedy adults, mainly Jews. The Director of the Jewish Orphanage of Sosnowiek, Mr. Reznitsky, first seems a bumbling and mildly incompetent figure, but turns out to be corrupt and mean, when he sells David as a virtual slave to a factory at the other end of town. The owner and overseers at the factory have no compassion for the children and are willing to set them to the most dangerous positions, tossing them out on the street if they injure themselves or become too big to crawl under the machinery to sweep up remnants and dust. Miriam finds out that her brother has been taken away as a virtual slave and, along with Ben—a boy two years older than herself from the orphanage—in a childish way plan to rescue the seven year-old but have no idea about what to do afterwards, knowing that Miriam’s grandparents cannot afford to take him back. Only by a lucky chance, when she sneaks into Reznitsky’s office, does Miriam come across some incriminating documents which, again by sheer luck, she is able to pass on to the directors of the orphanage, thus bringing about the director’s dismissal and a reformation of the institution. The factory owners are also arrested for breaking child-labour laws. These fairy-tale-like rescues ring hollow as the German Blitzkrieg approaches and the unstated Final Solution gradually begins to crystallize.

What this little story for twelve- to fourteen-year-olds leaves the readers to grapple with are the social facts of poverty and the meanness of adults who try to exploit the children around them, and the helplessness of most of the poor to find justice against corruption and greed. In the end, Miriam has to go back to work for the butcher, David to return to the orphanage albeit with a promise to see his relatives once a week, and Ben to enroll as an apprentice locksmith with the grandfather. These are very small remedies in an extremely painful world, and the future spells at best greater suffering and death in the near future.

The back-cover blurb tries to make Miriam and Ben heroes in the rescue of David from the clutches of men like Mr. Reznitsky and the factory owner, but what is narrated shows their efforts to be nugatory, with the temporary relief, such as it is, dependent on luck—as with the dependence on the Ouija board in the previous book. Good teachers and wise parents will have to help young readers see this and not allow children to come away thinking that determined children shielded by their innocence can go out and challenge the evils of the world. Considering the massive destruction of the world war and the millions murdered in the Holocaust, this is a minor incident—partly fictionalized, the author tells us, from oral reports she received among Jewish friends and relatives in Canada—and no model for action in the real world. It is frightening, perhaps too frightening, for children to contemplate, and yet, perhaps, given the mild cushioning of Dublin’s telling of the story, a small opening to mature acceptance of how dangerous the world is and has always been.

The third book by Anne Dublin, 44 Hours or Strike!, seems addressed to adolescents and young adults and takes an important event in the history of organized labour in North America. A little more than a .jpg) decade past the more famous Triangle Building Fire in New York City that was followed by a major strike by the ILGWU in which, as I mentioned, my grandmother’s brother Abraham Rosenberg played a part and was subsequently shot in the stomach by Pinkerton Men who called at his home in Brooklyn, the stop-work in Toronto in 1931 led to some important reforms. This was, for me, in my childhood, a formative tale, a piece of real family history. From it I trace a nagging suspicion of all vested authority, including teachers in school, politicians and supposedly important celebrities. When any is held up as a hero, especially when the roles they actually play in society has nothing to do with the expertise they claim to have or are imagined to inhere in their recognizable faces, I step back and sometimes walk away. It’s not just those people famous for being famous, but all those actors or singers who confuse themselves with the characters they play or the themes they sing about. I doubt that they are acting at all in any artistic way: their real life persona is equally shallow as the publicity photos and sound bites.

decade past the more famous Triangle Building Fire in New York City that was followed by a major strike by the ILGWU in which, as I mentioned, my grandmother’s brother Abraham Rosenberg played a part and was subsequently shot in the stomach by Pinkerton Men who called at his home in Brooklyn, the stop-work in Toronto in 1931 led to some important reforms. This was, for me, in my childhood, a formative tale, a piece of real family history. From it I trace a nagging suspicion of all vested authority, including teachers in school, politicians and supposedly important celebrities. When any is held up as a hero, especially when the roles they actually play in society has nothing to do with the expertise they claim to have or are imagined to inhere in their recognizable faces, I step back and sometimes walk away. It’s not just those people famous for being famous, but all those actors or singers who confuse themselves with the characters they play or the themes they sing about. I doubt that they are acting at all in any artistic way: their real life persona is equally shallow as the publicity photos and sound bites.

Accompanied by contemporary photographs related to the strike, Dublin’s book sets before its young readers some major issues concerning the exploitation of workers in still-existing sweat-shops, the difficulty of maintaining solidarity among workers in the several factories involved, the bias and cruelty shown by police and prison officials against the strikers. Most of all, by focusing on two sisters, Sophie and Rose, the short historical novel deals with the personal impact of the struggle by organized labour for recognition and for decent wages and safe workplaces.

Both sisters have moreover recently lost their father and have to do their best to help at home with a sickly mother. During the Depression they neither have the luxury of enjoying their adolescent years. They must learn to grow up quickly, and young persons’ novel follows each of them in this period of personal and public crisis.

Rose, the older sister who helps as an organizer in the strike and is manhandled by the police trying to control the picket line and then sent unfairly to a woman’s reformatory for disorderly conduct, a place where she encounters for the first time in her life the darker side of life and meets the women who exist on the other side of the law. Rose also has to confront sexual groping by one of the female guards, although this form of abuse is more suggested than described. Sophie, the younger sister, tries to mediate between her mother and the facts of what is happening at the factory and to Rose and then has to look after the older woman who falls down on the steps while leaving the police station. If Rose’s experiences bring up the issues of why workers strike and how the civil and judicial institutions serve the vested interests of middle-class society, certainly matters young readers need to study and discuss in school with teachers and at home with their parents; Sophie’s abrupt passage from innocence to a recognition of how harsh and unjust the real world can be provides its own questions for classroom debates and at home conversations.

Each of the books discussed so far have been written to introduce young people to topics they need to investigate further on their own and discussions must be such as neither to frighten the readers into pat answers, even as they do not hide their sympathy for the oppressed and the victims of social inequalities.

As the two sisters join the strikers on the picket line, they see other people, as poor and as desperate as they, walk into the factory to take their jobs. Merely dismissing them as scabs, however, does not explain why those strike-breakers feel they must put aside class solidarity to feed their families. Similarly, when Rose meets fellow inmates at the reformatory, thieves, prostitutes and vagabonds, she and they at first feel no empathy for one another. Gradually the confrontation leads to some understanding and friendship, at least with some of the more hardened criminals. These facts in the fiction raise different kinds of questions about people from dissimilar backgrounds, religions and domestic experiences. In one way, these matters are secondary to Dublin’s main concerns in the book; in another, as in the previous books, they are perhaps the most important learning aspects to the stories. Everything does not fall plop! into goodies and baddies, fixed categories of social difference, and ready-made responses to the complex world we all have to live in. The narratives are exemplary tales, but not simplistic allegories.

These three books are novels for young people and so, while based on historical events, they simplify the complicated matters of politics, economics and social relations. Similarly, by filtering the thoughts and young people, through the words and silent speech of children at various ages, they perforce avoid an abstruse vocabulary, a complicated syntax, and an elaborate grammar. Yet, at the same time, the prose is a bit awkward as the little girls who represent the historical moment fumble for words and seem to slip past thoughts too advanced for them to grapple with. Nevertheless, these short novels are pleasant to read. By not reducing moral problems to simplicities, they imply more than they say—and for adults to understand. For this all three titles deserve praise.

What the author has not attempted to do, however, is to shift focus away from two factors which may make these books not easy to sell outside of Canada in the rest of North America or even elsewhere in the world. The usual setting is specific, in Toronto, Ontario, or historically set in pre-war Poland, and the main characters are Jewish. It seems that on occasion other writers, their editors, or publishers, ask for the details of the narratives be made more American, as it assumed that young people in America are not comfortable with people, places and things that are not familiar to them. This is something we see in commercial movies quite often, where such things as the police uniforms, street signs, accents of main characters and references to history are shifted the typical types of the USA (that is, a Hollywood version of normality, most annoyingly in the cloying sentimentality and precociousness of school-age boys and girls).

In the second matter, the Canadian Jewish identity and background of the people, events and ideas, they also avoid the Americanized sugar-coating of liberal families or Woody Allen stereotypes of religiosity. Questions of honesty, fairness, respect for elders and ideals of education are not watered .jpg) down. In addition, rationality and logic are not washed away by dreamy ideals. There is no question of privileging Judaism over Catholicism or Protestantism or even the secularism of contemporary Canadian society, but in each of these stories—about a strike in the 1930s, about poverty in Poland on the brink of World War Two, about a terrible storm to hit Toronto in the 1950s—there is an implicit sense that a Jewish child will be on the side of justice, will identify with the underdog, and that life is something to be endured with dignity and loyalty to the family. It is not about competition for limited wealth and material goods, trying to succeed whatever the obstacles, which may include other people’s well-being, and holding true to one’s dreams no matter how preposterous they seem to others. Absent the American dream, everything does not end up with a pink bow and shared smile. Let us advise children to be realistic, to have common sense, and to be sceptical about magical cures and impossible dreams. I thank my lucky stars I was born before refrigerator magnets were invented!

down. In addition, rationality and logic are not washed away by dreamy ideals. There is no question of privileging Judaism over Catholicism or Protestantism or even the secularism of contemporary Canadian society, but in each of these stories—about a strike in the 1930s, about poverty in Poland on the brink of World War Two, about a terrible storm to hit Toronto in the 1950s—there is an implicit sense that a Jewish child will be on the side of justice, will identify with the underdog, and that life is something to be endured with dignity and loyalty to the family. It is not about competition for limited wealth and material goods, trying to succeed whatever the obstacles, which may include other people’s well-being, and holding true to one’s dreams no matter how preposterous they seem to others. Absent the American dream, everything does not end up with a pink bow and shared smile. Let us advise children to be realistic, to have common sense, and to be sceptical about magical cures and impossible dreams. I thank my lucky stars I was born before refrigerator magnets were invented!

__________________________________

Norman Simms taught in New Zealand for more than forty years at the University of Waikato, with stints at the Nouvelle Sorbonne in Paris and Ben-Gurion University in Israel. He founded the interdisciplinary journal Mentalities/Mentalités in the early 1970s and saw it through nearly thirty years. Since retirement, he has published three books on Alfred and Lucie Dreyfus and a two-volume study of Jewish intellectuals and artists in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Western Europe, Jews in an Illusion of Paradise; Dust and Ashes, Comedians and Catastrophes, Volume I, and his newest book, Jews in an Illusion of Paradise: Dust and Ashes, Falling Out of Place and Into History, Volume II. Several further manuscripts in the same vein are currently being completed. Along with Nancy Hartvelt Kobrin, he is preparing a psychohistorical examination of why children terrorists kill other children.

More by Norman Simms here.

Please help support New English Review.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link