Book Review – Inside Tucker’s World

by Bruce Bawer

During the last few years, the term TDS, meaning “Trump Derangement Syndrome,” has acquired a secondary meaning: “Tucker Derangement Syndrome.” Or, at least, it should have, because the leftist hostility directed at the longtime TV host comes close to rivaling that directed at the ex-president with whom he, more than anyone else on cable news, is so strongly identified.

If Trump is the man who challenged the Beltway uniparty in the name of American liberty and government by the people, leading millions of voters to realize that a great many Republicans were as fully a part of the swamp as Democrats, Tucker Carlson is the man who took on the cable news media consensus, demonstrating that Fox News is, in many ways, less a real alternative to CNN and MSNBC than a controlled opposition, on whose airways only a certain degree of dissent from mainstream orthodoxy is permitted. If Trump’s betrayal by many GOP leaders – from Bob Barr to Mike Pence – opened the eyes of a great many of his supporters, Tucker’s expulsion from Fox News illuminated the grim reality that pretty much all of America’s corporate news organizations are, in the end, tainted tools of the cultural elite.

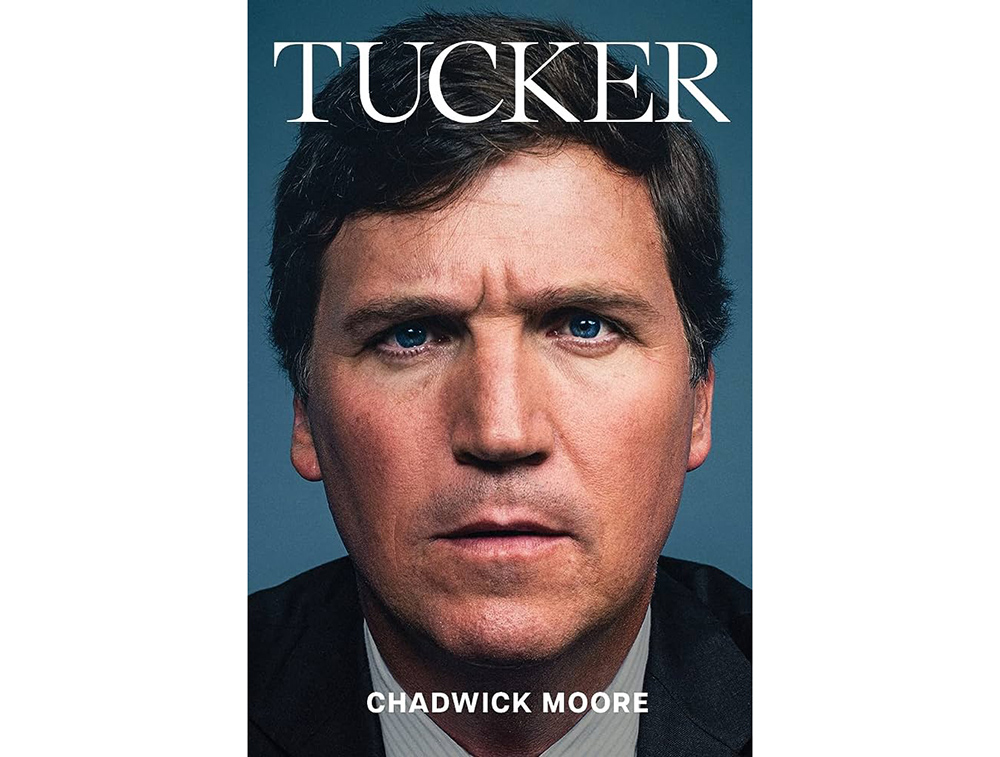

Tucker’s unexpected transformation from jewel in the Fox News crown to fully independent voice on Twitter – sorry, X – is the latest twist in a life story that Chadwick Moore, a former guest on Tucker’s show as well as on other Fox News programs (notably The Five), tells with verve and admiration in his estimable new biography, Tucker. If there were nothing else to praise about it, I would give Moore props for writing the first non-fiction book I’ve read in quite a while that doesn’t have a long, unnecessary subtitle. But, in fact, there’s a lot more to like here. Moore has figured out how to cover the bullet points about Tucker’s childhood and youth without loading us down, in the opening chapters, with details that we don’t really want or need to know.

The bottom line, which Moore conveys vividly, is that Tucker, who I’ve always vaguely gathered was a scion of wealth, was in reality the son of Lisa, a spoiled rich San Francisco girl turned hippie (now deceased) who abandoned her husband and her two sons when the boys were little, and Dick, who began his life in a Massachusetts orphanage, raised his boys on his own, went on to be a TV news anchor in San Diego and a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, and is still going strong in his eighties.

Moore tells us enough about Tucker’s parents to enable us to see just how strikingly different they were – the unholy mess of a mother who stiffed her sons in her will, and the dutiful, down-to-earth father who couldn’t be prouder of his sons. (Dick, Moore informs us, is the kind of man who, “forty years after two of his own dogs died…still carries their pictures in his wallet.” What more do you need to know?) This knotty family background, Moore shows, played a huge role in shaping Tucker both personally and professionally. Having such an irresponsible mother and devoted father made him appreciate the profound importance of family love and loyalty.

And having a dad who was not just a journalist but an inquisitive, impartial journalist made him want to go into the same line of work. Moore quotes from something Tucker wrote in 2001: “My father was a reporter, and he embodied everything I associated with journalism. He was smart, curious, and relentlessly skeptical. It was impossible to bullshit my father. No one told journalists what to say. Reporters were free men, and they lived like it. If they could prove it, they could write it. Period.” Those were the days.

Never getting bogged down too long in any chapter of Tucker’s career, Moore leads us nimbly through it all: first, an entry-level job at Policy Review in Washington, then a year at the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, followed by a staff job at the just-founded Weekly Standard. In 2000 he made the move to TV, spending five years at CNN (The Spin Room, Crossfire) and three years at MSNBC (The Situation with Tucker Carlson) before moving on to Fox News. While there, he also co-founded the Daily Caller website.

I must admit that during most of these TV years I was only vaguely aware of the dapper guy with the bowtie: living in Europe, I never tuned in to MSNBC, couldn’t get Fox News, and only put CNN on when a major international news story broke. Nor was the Daily Caller on my list of regularly consulted websites. I’ve gathered from others that during most of his TV career, like many of those who later jumped onto the Trump train, Tucker was a more or less conventional Republican, accepting, perhaps without reflecting on it terribly much, the proposition that, practically speaking, American voters who hoped to make even the slightest difference in charting the nation’s course were obliged to support one of the two major party establishments over the other – to choose, that is, the lesser of two inside-the-Beltway evils.

Speaking of evil, among the highlights of Tucker’s career that Moore recounts is a 2012 article that I’d never heard of before. Co-written by Tucker and Daily Caller colleague Vince Coglianese, it reported on newly uncovered – and truly explosive – footage of a 2007 speech by then-Senator Barack Obama in which, addressing an audience of black ministers, he described America as (in Carlson and Coglianese’s paraphrase) “a racist, zero-sum society in which the white majority profits by exploiting black America.”

As the article demonstrated, Obama based this claim on what he had to have known was disinformation about the relative sums allocated by the federal government to the largely black area affected by Hurricane Katrina (which in fact received over $110 billion) and the largely white area affected by the 9/11 attack on the Twin Towers (to which the Bush Administration pledged only $20 billion). In other words, Obama was using blatant untruths to stir up racial hatred and resentment – presaging exactly what he would do, to such disastrous and lasting effect, once in office. He also delivered “a full-throated defense of Jeremiah Wright,” the anti-Semitic pastor whom he’d later throw under the bus (along with his white grandma).

The 2007 speech gave the lie to Obama’s meticulous attempt, throughout his first presidential campaign, to cultivate an image of himself as a benign racial healer and bridge-builder; had it made the national news at the time, it might well have ended Obama’s White House run before it began. But of course that’s why the speech didn’t make the national news at the time.

Among the more entertaining parts of Moore’s book are Tucker’s candid comments about the politicians and media figures he’s known – and, in a couple of cases, their comments about him. One surprise: Tucker was once a close friend of Hunter Biden, whose addiction problems he (a former alcoholic) sympathized with. But he never liked Jill Biden (“a nasty person…small-minded and dumb”) or Joe (“famously stupid…skin-deep, fake, and shallow, and the hair plugs, and face lifts, and the pat-you-on-the-back stuff”). Tucker also knew Mike Pence when the latter was “a young, obscure Indiana congressman,” and found him “creepy as hell…a totally sinister figure, craven and dishonest.” Don Lemon? He’s “the stupidest person who ever had a TV show.”

Yet Tucker likes Rachel Maddow, whom he worked with at MSNBC and whom he regards, despite their political differences – and, presumably, despite her chronic duplicity – as intelligent. (Maddow, Moore tells us, “was the only liberal media personality to so much as respond to an interview request for this book, and though she declined, it was very politely.”) Another Carlson friend was the late P.J. O’Rourke, whose own carefully crafted image as a gadfly was belied, at least in his later years, by his supremely cozy inside-the-Beltway connections, and who broke off his friendship with Tucker over – yes – the latter’s support of Trump.

Then there’s Bill Kristol, Tucker’s old boss at the Weekly Standard and now one of the most ardent of never-Trumpers. In 1999, Kristol oozed praise for Tucker, calling him, among much else, “a witty writer and storyteller”; nowadays, however, notes Moore, Kristol’s “obsessive” tweeting about his former employee “regularly veers into lunatic territory.” (In one tweet, Kristol even compared Tucker to Leni Riefenstahl.)

And what of Trump? Tucker’s thoughts on the former president fill several extremely interesting pages. “I love Trump,” he avers, but is quick to add that he views him as a lousy manager and inept “political tactician” with a poor understanding of politics, and hence an “ineffectual president.” But Trump the person? “To have dinner with Trump is one of the great joys in the world. If you were to assemble a list of people to have dinner with, Trump would be in the top spot”; he’s “a wonderful host” and an “incredibly amusing, charming, dynamic” dining companion. And he’s more: in 2018, after Antifa radicals attacked Tucker’s home, Trump – who, needless to say, was president at the time – phoned Tucker’s wife, Susie, and offered to “come stand at [her] front door.”

She thanked him but turned down the offer, whereupon, before hanging up, he offered one closing thought: “I just want you to know, Susie, there’s a lot of love in this world.” As Susie tells Moore, that last line from Trump has “become kind of a mantra” for her: yes, there is a lot of love in the world, and “that’s what you have to focus on.”

To be sure, if you want to keep believing that the world is full of love, it helps not to watch TV (Tucker doesn’t own one) or use social media (he doesn’t); it also helps to live, as he does, far from the seats of government and media power, broadcasting from rural Maine in the summertime and from the Gulf Coast of Florida in the winter.

Perhaps Moore’s most effective accomplishment in this fine book is that he paints a thoroughly convincing three-dimensional portrait of a man who, deep down, is far less preoccupied with politics per se than with family, faith, and the enduring moral and aesthetic questions – which, by the way, he considers intimately intertwined with one another. (Moore quotes Tucker not only enthusing over great architecture but also pointing out that it doesn’t happen in a vacuum: “Noble ideologies produce beautiful results. Poisonous ideologies produce ugliness. There’s a reason the architecture in Bulgaria in 1975 was hideous – because Sofia in 1975 was controlled by the Soviet Union.”)

Climate hysterics and lovers of environmental overregulation view Tucker as an enemy, but while their purported concern for the planet tends to be ideologically driven, Tucker is the real thing, a genuine tree-hugger; moreover, while for the ideologues fretting about the environment means despising homo sapiens as a blight on the planet, for Tucker it means recognizing that living with, taking care of, and drawing sustenance from nature is a vital, soul-enriching part of human life. “Why would someone ever plant an oak tree?” he asks. “It’s because someday it will be this majestic thing that people they never knew will love and enjoy.”

What else? He believes in silence. He loves looking at the stars. Laugh, if you wish. Your loss. I buy every bit of it. While other top-earning journalists spend their lives in an elite urban bubble, Tucker prefers interacting with ordinary Americans from whom, as we discover, he routinely learns a lot. Briefly put, the Tucker we meet in this book is a highly impressive, utterly simpático, and all-around charming fellow indeed. This won’t surprise most of his fans, who are also Trump fans, and who – unlike the clueless clowns on the left who grossly misread both men – can sense, with him as with Trump, what kind of heart beats in his chest.

Yes, like Trump, Tucker has a lot more dough in the bank than most of them, but, far from dismissing them as deplorables or thinking of them as members of some alien, exotic, uneducated underclass (cf. David Brooks), he likes them, cares about them, respects their values, and is genuinely curious about their lives. Those qualities are a big part of what makes Trump a national hero, and they also play a major role in making Tucker a trusted, even cherished, voice of truth, decency, and unashamed patriotism on an otherwise exceedingly debased and dishonest media landscape.

First published in the Jewish Voice.