British Museum:Inspired by the east – how the Islamic world influenced western art

A friend asked me to accompany her to this exhibition at the British Museum recently. The Museum website says

Artistic exchange between East and West has a long and intertwined history, and the exhibition picks these stories up from the 15th century, following cultural interactions that can still be felt today. Objects from Europe, North America, the Middle East and North Africa highlight a centuries-old tradition of influence and exchange from East to West.

Artistic exchange between East and West has a long and intertwined history, and the exhibition picks these stories up from the 15th century, following cultural interactions that can still be felt today. Objects from Europe, North America, the Middle East and North Africa highlight a centuries-old tradition of influence and exchange from East to West.

Conceived and developed in collaboration with the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia, Inspired by the East: how the Islamic world influenced Western art includes generous loans from their extensive collection of Islamic and Orientalist art.

But as explained above, the exhibition omits any influence from Islam as expressed in Asia or the Indian sub continent or beyond to Malaysia and Indonesia. That definition of the Orient is the one of North Africa, the Middle East and Asia Minor, not as I was brought up to include, the Far East as far as Japan. But never mind.

When it opened the Guardian review said of the exhibition that it

…attempts to present orientalist art as not only one where western artists traded in cliche, but also to show how portrayals of the east in the west were more than just racist pastiches. It attempts to present orientalist art as a sort of cultural exchange, rather than plunder, more of a long-term interaction between east and west that influenced not just paintings but also ceramics, travel books and watercolour illustrations of Ottoman fashion. It also presents orientalism as an effort to understand other cultures at a time when there was not much travel,

Prayer is a common theme in orientalist art, as common as the trope of the harem. The exhibition’s selections also tease out another element of prayer that perhaps appealed to a certain nostalgia among western artists – the exclusively male nature of it.

Whether it is in individual or group prayer, men are portrayed in a sort of windswept nobility . . . This is the most striking aspect of the exhibition – that there was a time when images of Muslims and Islam were not toxic, when Islam was seen as exotic and religious observance something to long for. It is a sad observation that the west has gone backwards in its respect for and appreciation of Muslim culture and faith. If the orientalism of the past was patronising fetishisation, it is still a far more respectful perspective than the fearful one that predominates today.

Overall – and this is made clear in the introductory notes to the exhibition – this is an attempt to reclaim orientalist art from its sinister connotations and strip it back to what the exhibition nudges you towards thinking it was: curiosity and interest in a different culture when the west was beginning to pass from one era to the next.

In the current political climate, where prejudice against and suspicion of Muslims is commonplace, this is a refreshing initiative. But should we really be grateful to the orientalists for depicting Muslims as just a little bit more human than how they are often portrayed today?

One of the most recurring subjects in Orientalism was the harem. These were private, women-only spaces which no male could ever access, but that didn’t stop European artists letting their imaginations run wild. They now had the perfect excuse to paint women in various states of undress, in scenes that might otherwise have been deemed pornographic in London or Paris.

Strangely, there’s barely a harem scene included at the British Museum. Nor, for that matter, is there a single painting by Eugène Delacroix, who – with work such as The Fanatics of Tangiers in the 1820s and 1830s – was the godfather of Orientalist art. There’s no look either at 20th-Century artists such as Matisse who, though not out-and-out Orientalists, were undoubtedly influenced by the movement.

These omissions can be put down to the fact almost all the exhibits are from the BM’s own collection or that of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia (IAMM), where this show tours next year. In other words, the pool of works from which Inspired by the East is drawn is disappointingly small.

I think that last sentence is very fair comment.

It started uncontroversially enough with beautiful Turkish and Persian ceramics, mostly in mouthwatering shades of blue, turquoise and green and the European ceramics that almost copied them.

Bottom left a 17th century tile from Damascus Right Made in England by Minton 1870.

Bottom left a 17th century tile from Damascus Right Made in England by Minton 1870.

As I browsed further my not very submissive mind spotted shedloads of taqiyya and dissembling.

I rather liked this exhibit.

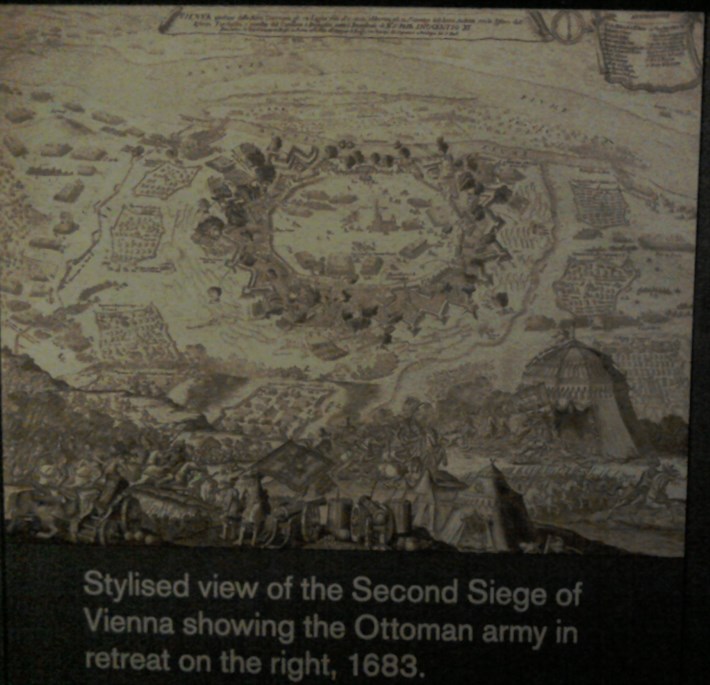

It’s a helmet given to Polish King Jan Sobiesski III in 1683 after the Ottoman Empire was defeated at the Gates of Vienna, or as it is described in the exhibition The Second Siege of Vienna. The Ottoman Empire is described as “Europe’s most powerful neighbour, twice advancing as far west as Vienna’. We know that this was jihad – yet another chapter in this 1400 year long attempt to conquer and subdue Western Europe under Islam. Apparently King Jan Sobiesski III stored this in his treasury as booty, not just a symbol of his victory but because he admired the Ottomans so much. Admiration or not I’m heartily glad he and the armies under his command saved Western Christian Europe then. I don’t know how the Islamic Arts Museum of Malaysia got hold of it from Poland but over the last 300 years everything has a price.

It’s a helmet given to Polish King Jan Sobiesski III in 1683 after the Ottoman Empire was defeated at the Gates of Vienna, or as it is described in the exhibition The Second Siege of Vienna. The Ottoman Empire is described as “Europe’s most powerful neighbour, twice advancing as far west as Vienna’. We know that this was jihad – yet another chapter in this 1400 year long attempt to conquer and subdue Western Europe under Islam. Apparently King Jan Sobiesski III stored this in his treasury as booty, not just a symbol of his victory but because he admired the Ottomans so much. Admiration or not I’m heartily glad he and the armies under his command saved Western Christian Europe then. I don’t know how the Islamic Arts Museum of Malaysia got hold of it from Poland but over the last 300 years everything has a price.

There was a series of illustrations to the book One Thousand and One Nights aka Arabian Nights or Tales of the Arabian Nights. I rather liked this short film made in 1923 by Lotte Reiniger of the Tale of Prince Achmed. It reminded me of a Balinese puppet theatre show, or some of the work of Jan Pienkowski.

There were plenty of scenes of everyday life in North Africa or Egypt. No artist could fail to want to capture the colours of desert, sky, architecture and people. Even then the notes censure the artists.

“Local people were often depicted as living idle and responsibility free lives, reinforcing a misleading stereotype”.

Even the frames made for some paintings reflected their Islamic background. This is The Prayer by Etienne (Nasreddin) Dinet, a French painter who eventually converted to Islam. The calligraphy round the frame is, if I recollect the notes correctly, a version of the motto of the Moorish dynasty of Granada which translates as “There is no victor but Allah”

What the exhibition failed to mention is that many of the scenes and people shown in art were not necessarily Islamic, just because they lived under Islamic domination.

For example these two pictures, left the Custodian to the Entrance of the Temple Mount (a place of enormous important to Jews, and also to Christians) and right classic camels against the (ancient and pre-islamic by about 3000 years) pyramids.

And the women of the Harem, when a western artist was allowed access to sketch them, were Circassians. Described in the notes as ‘much prized in the harems for their beauty’ the notes omit to mention that these beautiful young women, often fair and blue eyed, were Christian slaves. We were told that lacking access to the harems the French painter Delacroix painted Jewish women until an Algiers merchant allowed him into his harem, when he was able to paint Women of Algiers in their Apartment.

This is one such Circassian woman painted by David Wilkie in 1840. She was part of the harem of an exiled Persian prince living at the time in Constantinople.

He described her as having “a little colour, full eye and lip, very long hair and rich dress; she had no expression and was perfectly silent”. I expect she didn’t dare say a word.

The paintings of harem women in a titillating state of undress were shown only in a couple of small prints attached to the notes under some drawings by Picasso, by which he had himself been inspired. I’m not sure (unless his diaries say so specifically) that there isn’t also a classical bath house background to that sketch. Picasso wasn’t short of 20th century contemporary inspiration around him either when sketching a nude.

The number of portraits (paintings, enamels and photographs) commissioned of themselves of Turkish Sultans, generals and statesmen shows that the Islamic prohibition of the living form is not, and was not, absolute across the Islamic world. There was a series of pictures by Muslim artists like Osman Hamedi Bey showing the influence of western Europe on them.

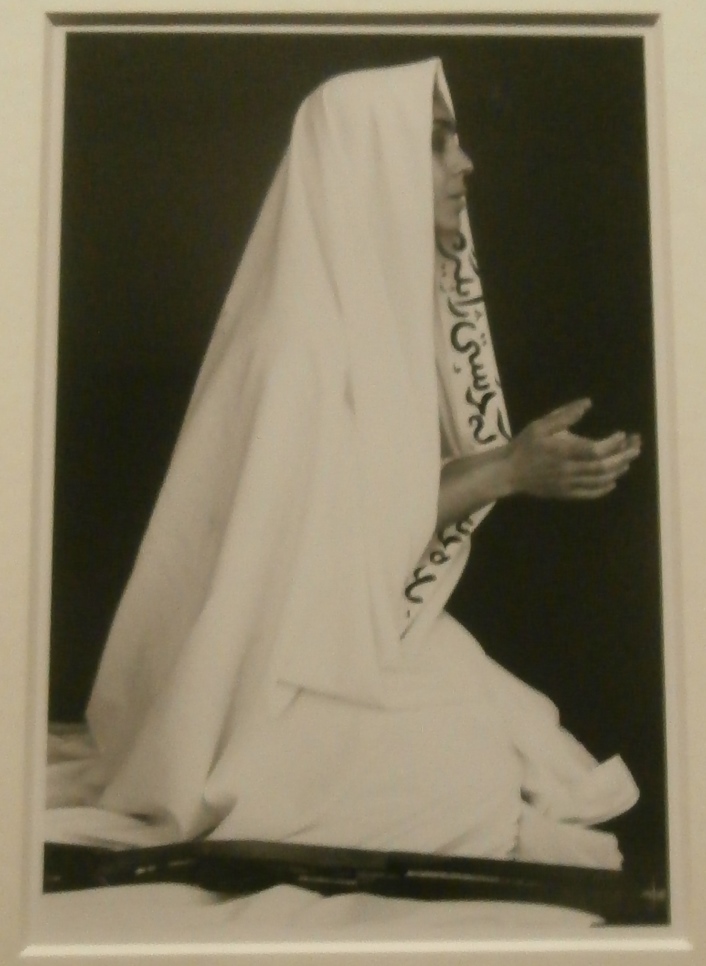

The final section was a series of modern artwork by Muslim and North African women who, as the British Museum website explained “continue to question and subvert the idea of Orientalism in their work and explore the subject of Muslim female identity.”

A photograph of the artist Sharin Neshat from her Women of Allah series. She wears a chador and while appearing to be at prayer she also has a gun by her side. She intends to symbolise female agency and subvert the passive portrayal of the women of the Orientalists. I’m not sure that actually works. A gun isn’t a toy, it’s a real threat.

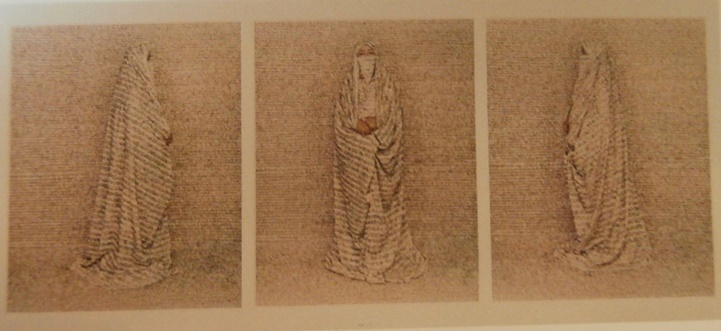

Then there was Women of Morocco by Lalla Essaydi. To quote the notes “Essaydi reimagines the harem paintings of 19th century Orientalism. She replaces the bright colours, nudity and luxury of such painting with monochrome settings, fully clothed women and strings of Arabic letters. Here women are active agents rather than passive objects subjected to the voyeuristic imaginings of European artists.”

I couldn’t see that three views of a woman behind a beige burka was somehow “active” while a lively girl in a cheerful frock playing music was a “passive” object. The beige burka reminded me more of Ayann Hirsi Ali and the late Theo Van Gogh’s Submisson. Except she had submitted.

I couldn’t see that three views of a woman behind a beige burka was somehow “active” while a lively girl in a cheerful frock playing music was a “passive” object. The beige burka reminded me more of Ayann Hirsi Ali and the late Theo Van Gogh’s Submisson. Except she had submitted.

One of a series of Persian costume 1842 by an unknown Qajar artist

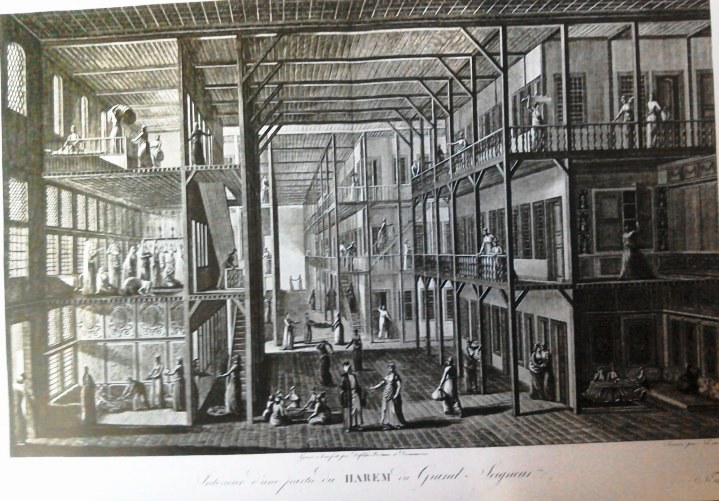

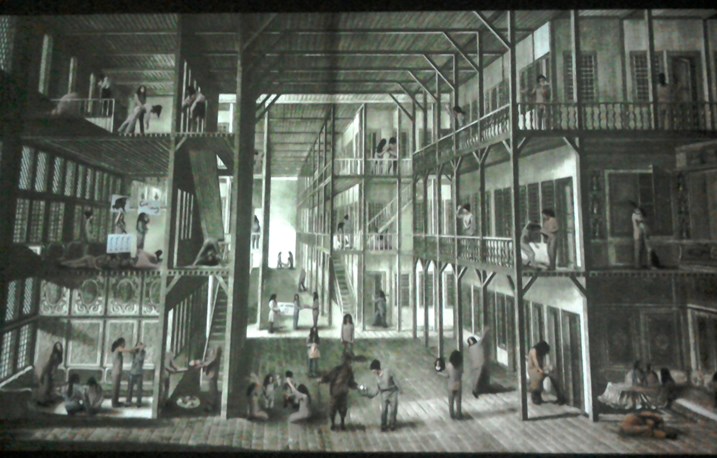

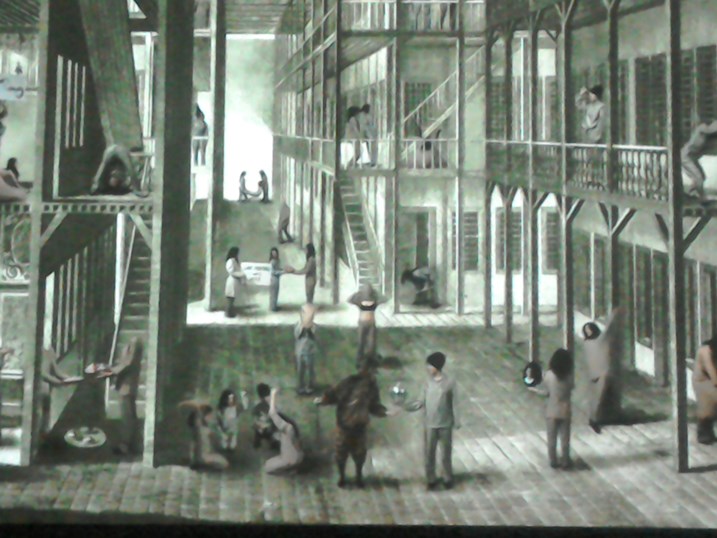

The final installation was the weirdest. It was an animation by Inci Eviner which took another harem picture, the black and white drawing by Antoine Melling, Interior of part of the harem of the Grand Seigneur and updated it to her ideas.

Melling had to imagine what was going on in the harem. And he imagined women in clothing much like the women he knew wore, doing things he knew women did. Some are at a table eating, some carrying parcels from one floor to another. Some seem to be praying, others chatting, hanging up or folding laundry. One pair of women are in an affectionate embrace, which may well be a hint towards a same sex attraction, or may not. It may be a hint of fantasy at ‘what women do when access to men is limited – oooh’. Or it may just be two women who are friends. The activities so far as I could see, and can see from the photograph I took and the postcard I bought, would not look out of place in a Jane Austen novel, with which it is (1819) contemporary.

Inci Eviner thinks differently. She says she ‘wanted to tear this scene ( masculine and pseudo-realistic) apart’

Her animation starts with the static Melling drawing. Sounds are heard of breathing, crying, and the clanging of metal as the figures turn from 19th century dress to women in modern shapeless trousers and tops. The clanging is from the central figure at the foot of the stairs who is repeatedly bashing a post. This noise continues throughout the animation. Eviner says these woman are protesting, praying and attempting to escape.

The praying does look like prayer. The protesters hold placards – so far so conventional. The escapers appear to be using the Blackadder technique. Stick underpants on head (or in this case a paper bag) and pretend to be mad. Very mad.

Nothing says ‘free me’ like fighting with a fellow concubine for possession of the communal cardigan (central staircase, first floor) or putting one’s head between the legs so as to kiss one’s own bottom, (left staircase first floor) or dressing up as a bear (foreground). I think the lady flashing her bra (next to Miss Paper Bag) is meant to be a protest. Other ladies have taken, or that’s what it looked like to me, the potential same sex attraction to a PRIDE conclusion. Others, bottom of left hand staircase have lost their heads completely.

Her execution isn’t as detailed as a Hogarth but his drawings of Bedlam was what her work reminded me of. As a depiction of the oppression of women under Islamic attitudes her work may have merit. As an attack on a European white man whose sin was to imagine that the women in a harem behaved just like his own female relatives and friends in France and Germany it is unwarranted.

Her execution isn’t as detailed as a Hogarth but his drawings of Bedlam was what her work reminded me of. As a depiction of the oppression of women under Islamic attitudes her work may have merit. As an attack on a European white man whose sin was to imagine that the women in a harem behaved just like his own female relatives and friends in France and Germany it is unwarranted.

I found the exhibition interesting in parts, simplistic in others, misleading in places. It closes in London soon and transfers to the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur from 20 June to 20 October 2020.

Photographs E Weatherwax London 2020