Carl Jung and the Nexus of Anthropology and Biology

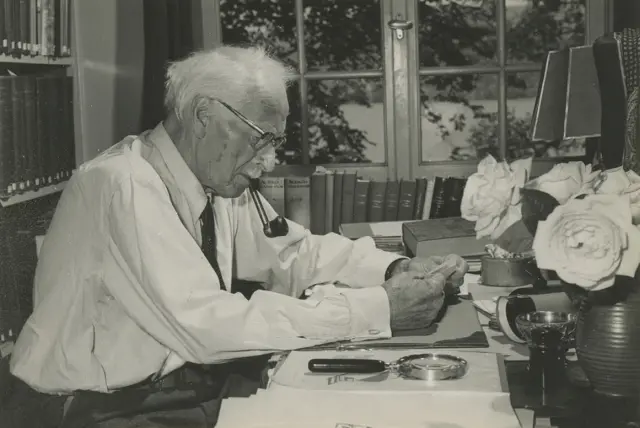

Carl Jung

Carl Jung

by Armando Simón

Ethology, the study of animal behavior, is the European version of (American) Comparative Psychology. The former has a heavier emphasis on the biological foundation of behavior as well as a focus on observations of animals’ behaviors in a naturalistic setting. Ethology is also noted by its broader perspective on the number of species being studied and Comparative Psychology in experimenting with principally two organisms, the pigeon and the ersatz lab white rat. As a result, for a long time, there was bitter rivalry between the two disciplines. Eventually, Ethology won out, and for good reason.

The culmination of this rivalry was the awarding of a Nobel Prize to Konrad Lorenz (Austria), Otto von Frisch (Germany) and Niko Tinbergen (Holland). Indeed, Comparative Psychology—though completely revamped—is now an endangered species and may soon become extinct.

Throughout, there has always been the dilemma of being bogged down in studying specific behaviors of an individual species, which are then inapplicable and ungeneralizable to another species, particularly as we go lower on the evolutionary scale, e.g., the locomotion of slime molds, the spawning of horseshoe crabs, or the chemoreception of ants. Nonetheless, the overwhelming range of behaviors studied so far in animals have been generalizable to not only other species and genera, but sometimes even family, order, class and phylum. Examples of these generalizable behaviors are aggression, displacement, habitat building, territoriality, migration, construction of dwellings, and the rearing of young. Obviously, the emphasis of studies on these subjects is because they appeal to researchers because they apply to us. Extension of general principles from the animal kingdom into the plant kingdom, however, has not been successful.

Apropos of this, something that is rarely, if ever, mentioned is the fact that both Ethology and Comparative Psychology lack a theory of any kind, much less a comprehensive theory. One attempt at this occurred in 1968, when Desmond Morris proposed his Naked Ape theory. It was not mentioned among respectable society, though intensely popular with the public (Morris may have been snubbed by his fellow ethologists, but he laughed all the way to the bank). The Naked Ape theory, however, applied only to humans.

Field observations of human beings by ethologists have yielded conclusions that many of the general principles observed in animal behavior are likewise applicable to humans who are, after all, animals. There are some behaviors which are consistently produced by Homo sapiens across cultures (whether simple or complex) and, on the other hand, some which are exclusively the peculiar characteristic of a given culture. An example would be, respectively, bowing of the head to authority and, on the other hand, culturally idiosyncratic hand gestures denoting an insult towards another person.

Along similar lines, and prior to cross-cultural investigation by ethologists, anthropologists (like Claude Lévi-Strauss, to some degree) noted that certain cultural institutions and beliefs (along with their behavioral concomitants) were present in all human societies regardless of the degree of complexity of a culture. Two examples would be the marriage and religion, though the details may differ in details across different cultures. At the risk of bringing down the wrath of colleagues for using the “i-word,” I would say that such institutions are “instinctual,” that is, they are an inherent part of what makes Homo sapiens a human being.

Nonetheless, proceeding onwards along the same path, we come onto Carl Jung. In regards to Jung’s writings, it has been joked that one either totally understands Jung and becomes an instant adherent of his views, or one simply does not understand what the hell he wrote. There is no “in between.”

Jung postulated that certain basic concepts were universally present in all human beings, regardless of the specifics of each culture, as part of what he called the collective unconscious of human beings. Examples of these archetypes would be the idea of the mandala, the hero, rebirth, or the malevolent trickster. Like the ethologists, and unlike his contemporary psychoanalysts, he based his conclusions on extensive historical and cross-cultural field studies outside of Switzerland, particularly in regards to the religion of different cultures and of different epochs. As such, his theoretical propositions should not be tarnished by association with the assertions of other psychoanalysts whose cultural outlook were extremely narrow and whose theoretical writings had little factual underpinnings and have even remained invalidated to this day, the most obvious being the ramblings of Sigmund Freud.

Heretofore, the ethologists have not recognized Jung’s theories as being a part of their field of study, though with closer examination by them it may prove to be otherwise. None other than E. O. Wilson alluded to the biological basis of archetypes. Perhaps there is a reluctance to do so since the concept of archetypes lie in the cognitive field, and ethologists/comparative psychologists study observable behavior. Even so, as Jung pointed out numerous times in his writings, these archetypes are, indeed, constantly manifested in observable behaviors. An ethological approach to Jungian archetypes should yield fruitful research in the future. Simply put, archetypes are instincts. After all, they must be based in human beings’ biology.

By the same token, whereas Jungians have viewed the archetypes as a purely psychic manifestation, it would be equally productive if they began examining them from a biological viewpoint. Both approaches could possibly yield further, productive, insights. To be perfectly honest, however, I cannot envision how we could go about testing for the presence of archetypes in animals other than people.

Perhaps some enterprising ethologist in the future may be able to follow this up experimentally. It would not be the first time that a scientific conundrum stumped researchers for decades before the problem was ultimately resolved.

Armando Simón is a retired psychologist and author of The Book of Many Books, Very Peculiar Stories and When Evolution Stops.