Charles De Foucauld, Who Took Islam’s Measure, To Be Canonized

by Hugh Fitzgerald

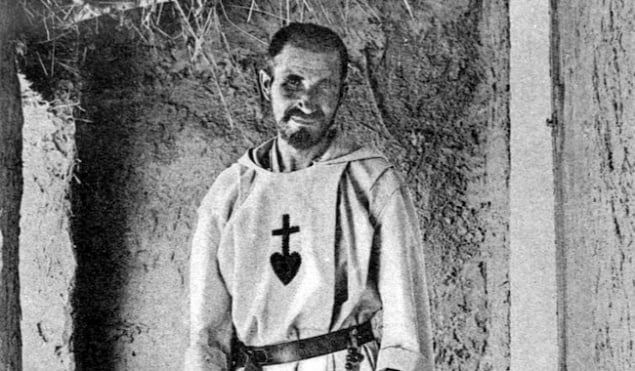

This does not signify a change in Pope Francis’s own views of Islam. It only means that Charles de Foucauld (1858-1916), a French priest who lived among Muslims in Morocco and Algeria, where by his own example he hoped to promote their conversion to Christianity, has been willfully misunderstood by the Vatican, for de Foucauld was no admirer of Islam. If he were alive today in France he would be supporting Marine Le Pen.

The story is at the Church Militant:

Pope Francis is to canonize a French priest who warned of the resurgence of Islamic imperialism and the impossibility of integrating Muslims into French society unless the Church converted Muslims to Christianity.

Pope Francis apparently is unaware of Charles de Foucauld’s views on Muslims and Islam. They were nothing like what Pope Francis believes; de Foucauld took a very dim view of Islam, and regarded Muslims as a threat to the French whom they hoped one day to “subdue.”

If he did not express these views openly, that was because he was in North Africa living with Muslims. He did not proselytize, believing that he had to slowly win the trust of Muslims, to prepare the mental ground for others who would come after him and convert them. De Foucauld’s real views can be found in his Letters.

“In general, with some exceptions, as long as they are Muslim, they will not be French, they will wait more or less patiently for the day of the Mahdi [Islamic messiah], in which they will subdue France,” Blessed Charles de Foucauld warned in his 1916 letter to René Bazin, his future biographer.

“If, little by little, slowly, the Muslims of our colonial empire in northern Africa do not convert, there will be a nationalist movement similar to that of Turkey,” de Foucauld predicted, explaining that the Muslim “intellectual elite” will have “lost all Islamic faith” but will use Islam to “influence the masses,” and ordinary Muslims will remain “firmly Mohammedan, brought to hatred and contempt for the French by their religion.”

“In sentiments that would now be outlawed as Islamophobic, de Foucauld prophesied an Islamic political threat to Christian civilization, warning of the dangers of Muslims left untouched by the love of Christ,” a French-speaking member of the Little Brothers of Jesus, a religious society inspired by de Foucauld, told Church Militant.

“The task of whether or not to treat de Foucauld as an Islamophile or an Islamophobe will define whether or not European culture succumbs to Islam or converts it,” the Normandy-based Catholic theologian observed.

However, shortly after the Vatican cleared de Foucauld’s canonization on May 27, Fr. Andrea Mandonico told Vatican News that the martyr should be hailed as a “prophet of interreligious dialogue between Christianity and Islam.”

Professor Mandonico teaches a course on Charles de Foucauld at the Gregorian University, which aims “to show how a fraternity between Christianity and Islam is possible … in the dialogue that does not impose itself, that does not ask for conversion, a dialogue in ‘universal brotherhood’ as … stated in the recent document on Human Fraternity,” signed between Pope Francis and Grand Imam of Al-Azhar Ahmed al-Tayyeb in Abu Dhabi Feb. 2019.

Charles de Foucauld was not engaged – despite Professor Mandonico’s claim – in “interreligious dialogue.” He did not believe it possible for there to be any true dialogue with Islam, so militantly hostile to Christianity. He was attempting to win by his self-effacing behavior the trust of individual Muslims, to reduce their Qur’an-inculcated hostility, and to prepare Muslim minds for conversion to Islam, which he knew would take time. He talked with the Muslims – Arabs and Tuaregs — among whom he lived, he offered himself as an unthreatening example of a devout Christian cleric, but that did not constitute “interreligious dialogue.”

La Croix praised the former cavalry officer as “a great figure of interreligious dialogue.” In an interview, Sr. Odette, a member of the Little Sisters of Jesus based in Paris, said: “At a time when there is so much talk of interreligious dialogue, he is a great figure of that dialogue through his apostolate of prayer, silence and friendship with his Muslim brothers and sisters.”

Another enthusiast, a Sister Odette, is apparent unaware of how De Foucauld saw his mission. He was not “a great figure…of interreligious dialogue” at all; he offered his own charitable and ascetic self, rather, as a way to win over Muslim hearts to recognize that not all Christians were the enemy. He could offer “friendship” to Muslims, but not renunciation of his own very clear Christian beliefs, which he did not dwell on, as they were regarded by Muslims with horror and hostility.

Writing in The Tablet, Christopher Lamb described the missionary to the Tuareg population of the Ahaggar region as a “model of dialogue and charity” who “showcased a ministry of presence.’”

“It is an evangelization method which is the opposite of proselytizing. Living in a Muslim country he did not seek to preach, or perform great acts of bravado but to live at the foot of the cross,” writes Lamb.

Christopher Lamb recognizes that De Foucauld’s intent was to “evangelize” in the most modest of ways, by offering himself as an example of a believing Christian, who never openly proselytized, and who proceeded very gradually to win Muslim affections. “Living in a Muslim country he did not seek to preach” — that was because that could cause him to be murdered. “Great acts of bravado” similarly refers to any too-obvious attempt, besides preaching, to win Muslim minds and hearts for Christianity; that too could have led to his death.

In The Tablet the liberal Catholic Christopher Lamb comments: “At a time when political strategists, and some inside the Church, wish to present a ‘clash of civilizations’ between Islam and Christianity and call for the ‘Judeo-Christian’ west to be defended, de Foucauld offers another way.”

Lamb misconstrues De Foucauld’s views. The fact that he did not proselytize but sought another means to open Muslim hearts to Christ, does not mean he had a favorable view of Islam. In his letters, Charles de Foucauld was very clear about that “clash of civilizations” which Lamb claims he did not believe in. He saw the political threat of Islam to the Christian West. He understood the deep-seated immutable hostility of Muslims toward Christians, that he had learned about from living with Muslims themselves. He predicted the clash of civilizations in his letters, explaining that in the future the Muslim “intellectual elite” will have “lost all Islamic faith” but will still use Islam to “influence the masses,” and ordinary Muslims will remain “firmly Mohammedan, brought to hatred and contempt for the French by their religion.” De Foucauld prophesied “an Islamic political threat to Christian civilization, warning of the dangers of Muslims left untouched by the love of Christ.”

Charles de Foucauld, a Catholic priest who is about to be canonized by the Vatican, spent much of his adult life living alone among Muslims, first among Arabs in Morocco, and then among Tuaregs in Algeria. He wished for, but did not himself attempt, the conversion of Muslims. He instead saw his mission as one of offering himself as an example of a self-effacing inoffensive priest, living an ascetic life of prayer, that might lead some Muslims to unharden their hearts toward Christianity.

To repeat from yesterday’s post: “In The Tablet the liberal Catholic Christopher Lamb claimed that “at a time when political strategists, and some inside the Church, wish to present a ‘clash of civilizations’ between Islam and Christianity and call for the ‘Judeo-Christian’ west to be defended, de Foucauld offers another way.”

That is not true. De Foucauld was very clear about the enmity between Islam and the West, To repeat from yesterday: He predicted the clash of civilizations in his letters, explaining that in the future the Muslim “intellectual elite” will have “lost all Islamic faith” but will use Islam to “influence the masses,” and ordinary Muslims will remain “firmly Mohammedan, brought to hatred and contempt for the French by their religion.” De Foucauld prophesied “an Islamic political threat to Christian civilization, warning of the dangers of Muslims left untouched by the love of Christ.”

But the Normandy-based Little Brother [who spoke to the Church Militant reporter] said that he rejected Lamb’s liberal spin: “The truth is that de Foucauld longed for the full and fervent conversion of Muslims into the deep and wondrous experience of Jesus that Catholicism mediates.”

“Those who claim de Foucauld’s life offers an example of passive benign cohabitation with Islam have not read his letters. He agonized over finding ways to gain the trust of the Muslims so conversion could follow. He was preparing the ground for future missionaries to carry out the task of conversion,” the Little Brother stressed.

“He [de Foucauld] also criticized the West for not acknowledging the violence the Koran encourages towards Christians and recognized the impossibility of Muslim converts remaining with their communities who would otherwise ostracize and kill them. He even accused Christian Europe of not caring enough either for the ‘Musselman’ or for Jesus to even try to convert them,” the Little Brother added.

Speaking to Church Militant, canon law expert Dr. Catherine Caridi insisted that “Fr. de Foucauld was being canonized for his heroic virtue and not just for being nice to Muslims or anybody else.”

Caridi, whose book Making Martyrs East and West: Canonization in the Catholic and Russian Orthodox Churches is considered an authoritative text on the canonization process, said: “The notion that de Foucauld upended his whole life to move to North Africa, simply because he wanted to live amicably among the Muslims without converting any of them is so erroneous, it’s almost laughable.”

“Father de Foucauld wanted to bring souls to Christ, as he himself had been brought to Christ through his spiritual re-conversion,” she said. “Having been stationed in North Africa in his military days, he had seen up close the native population — and wanted to present them with the example of a Catholic priest living a life of prayer, so as to gradually lead them to the true faith.”

Caridi explained:

The key word here is “gradually.” De Foucauld knew the Muslims were resistant to the Gospel and converting them would take time. He first lived among them quietly, acclimating them to the idea that there was in their midst a Catholic priest who treated them charitably and behaved with humility and simplicity. Many of them soon came to respect him — an important first step.

“Father de Foucauld wrote to Catholics in France, asking them to send him rosaries to give to the local people — specifying that the rosaries should have a medal in place of the crucifix. He knew that the Muslims would never accept a gift with a crucifix attached; but a medal would be seen as something more acceptable to them….

“Despite his earlier desire to convert to the religion of Muhammad, “Islam, for de Foucauld was ultimately void of truth,” Block writes, citing the French priest’s remarks: “I could see clearly that Islam was without a divine basis and the truth was not there,” and “these souls are lost and will remain in that state if we do not take measures to influence them.”

“According to Muslim writer Ali Merad, de Foucauld saw Muslims as “slaves of error and vice,” from whose “spiritual dereliction” he was present to rescue them….

Two versions of Charles de Foucauld are presented in this Church Militant article. One version assumes he was engaged in ‘inter-religious dialogue” with Muslims, that he had a favorable view of Islam, and that he refused to accept the inevitability of a “clash of civilizations.” None of this is true. This version ignores what he had learned about Islam over the decades of living among Muslims, and which he recorded in his letters.

Of course he was in no position to openly criticize Islam, nor could he proselytize as he would have been able to do in the non-Muslim world. In Muslim societies, either activity could lead to his death. What he hoped to do was to offer himself as an visible example of Christian faith, leading an inoffensive existence among Muslims who would be gradually won over by his example, their minds and hearts prepared to accept Christ, which de Foucauld assumed would have to wait to be accomplished by those who came after him.

The other, true version of Charles De Foucauld is this: initially he had a favorable view of Islam; at one point he even contemplated converting to it. But as he lived in Muslim lands – first in Morocco and then in Algeria – he came to see Islam as a dangerous faith. “Islam, for de Foucauld was ultimately void of truth,” the scholar C. Jonn Block writes, citing the French priest’s remarks: “I could see clearly that Islam was without a divine basis and the truth was not there,” and “these souls are lost and will remain in that state if we do not take measures to influence them.”

According to the Muslim writer Ali Merad, de Foucauld saw Muslims as “slaves of error and vice,” from whose “spiritual dereliction” he was present to rescue them.

These views could not be openly expressed by De Foucauld when he lived in Morocco and then Algeria. He confined them to his letters, the only outlet where he could securely unburden himself of what he believed to be true about Islam and Muslims.

Now we have the spectacle of the Vatican about to canonize someone who, were he alive today, would certainly be consigned by Pope Francis to the outer darkness for what the Vatican would describe as “islamophobic” views. The canonization of Charles d e Foucauld will provide a salutary occasion, for those of us who do not share Pope Francis’s views, to discuss what the French priest really thought of Islam (“without a divine basis and the truth was not there”), and about Muslims (“slaves of error and vice”). De Foucauld’s clear-eyed sense of the political threat that Islam poses to Western civilization – his observation that whatever a handful of elite Muslims might think, “ordinary Muslims will remain firmly Mohammedan, brought to hatred and contempt for the French by their religion,” and his prophesy of “an Islamic political threat to Christian civilization,” will receive – not a moment too soon — the wider diffusion they deserve, though without, we can be sure, the Vatican’s embarrassed blessing.