by James Stevens Curl

James Gillray: A Revolution in Satire by Tim Clayton

James Gillray: A Revolution in Satire by Tim Clayton

New Haven & London: The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, distributed by Yale University Press, 2022408 pp., 205 col. & b&w illus., £50.00

ISBN: 978-1-913107-32-1 hardback

James Gillray (1756-1815) was born in Chelsea, son of James Gillray (1720-99) and his wife, Jane Coleman (1716-97), who hailed respectively from Lanarkshire and Gloucestershire. The elder Gillray served in the army, and lost an arm at the Battle of Fontenoy (1745—so missed the campaign which ended in Culloden), becoming a Chelsea Pensioner in 1748. He also joined the Moravians in 1749, and supervised that sect’s burial-ground in Chelsea for over 40 years.

The Moravians sensibly held that humankind was fundamentally depraved, and perceived death as a welcome release from worthless life. However, they also gave their children excellent and wide-ranging education, albeit involving strict discipline, separation from parents, and spartan conditions. According to some commentators young Gillray as an adult was very widely read and well-informed. Not much is known about how he acquired his skills as a caricaturist, although something of the darkness of the Moravian outlook on life undoubtedly rubbed off on the young man, and entered his soul, for much of his work was extremely pungent, and often verged on a coarseness that can still shock, even today. We know that he was apprenticed to Harry Ashby (1744-1818), of Holborn, from whom he learned penmanship and techniques of engraving, and in 1778 was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools London, to study under Francesco Bartolozzi (1728-1815), and thereafter his draughtsmanship greatly improved.

During the 1780s Gillray emerged as a caricaturist, despite the fact that this was regarded as a dangerous activity, rendering an artist more feared than esteemed, and frequently landing practitioners into trouble with the law. Gillray began to excel in invention, parody, satire, fantasy, burlesque, and even occasional forays into pornography. His targets were the great and good, not excepting royalty. But his vision is often dark, his wit frequently cruel and even shockingly bawdy: some of his own contemporaries found his work repellent. He went for politicians: the Whigs Charles James Fox (1749-1806), Edmund Burke (1729-97), and Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan (1751-1816) on the one hand, and William Pitt (1759-1806) on the other. Fox was a devious demagogue (“Black Charlie” to Gillray); Burke a bespectacled Jesuit; and Sheridan a red-nosed sot. But Gillray reserved much of his venom for “Pitt the Bottomless”, “an excrescence … a fungus … a toadstool on a dunghill”, and frequently alluded to a lack of masculinity in the statesman, who preferred to company of young men to any intimacies with women, although the caricaturist’s attitude softened to some extent as the wars with the French went on.

As the son of a soldier who had been partly disabled fighting the French, Gillray’s depictions of the excesses of the Revolution were ferocious: one, A Representation of the horrid Barbarities practised upon the Nuns by the Fish-women, on breaking into the Nunneries in France (1792), was intended as a warning to “the FAIR SEX of GREAT BRITAIN” as to what might befall them if the nation succumbed to revolutionary blandishments. The drawing featured many roseate bottoms that had been energetically birched by the fishwives. He also found much to lampoon in his depictions of the Corsican upstart, Napoléon.

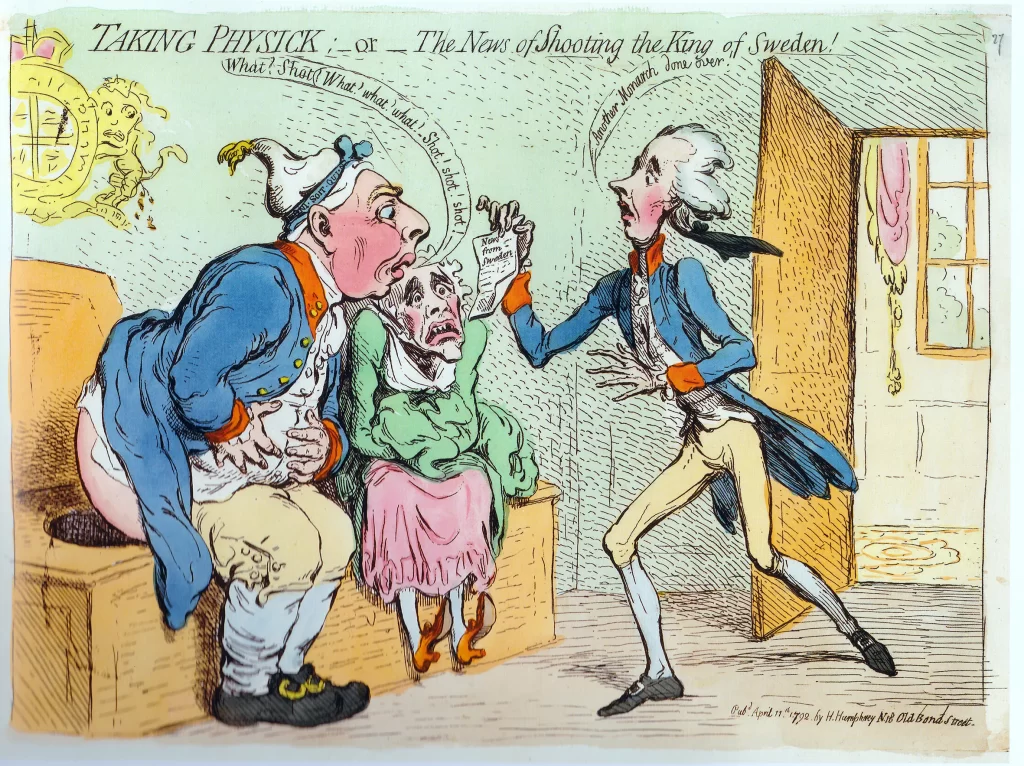

Gillray brought a coarseness and a viciousness to his caricatures of members of the royal family that amazed foreigners, but he was at his nastiest when traducing George III’s Queen (born Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz [1744-1818]), who is rather too often shown as a hideous old hag. Horace Walpole, who would not spare the vitriol when he deemed it necessary, said that the queen was “sensible, cheerful, and remarkably genteel”, and she was certainly cultured, so it is hard to see why Gillray was so hard on her (though he seems to have disliked foreigners of all kinds). In Taking Physick;—or—The News of Shooting the King of Sweden! (1792) the king and queen are depicted “At Stool” as Pitt rushes in with the intelligence that “Another Monarch” has been “done over!”, but poor Charlotte’s horrible image is extremely cruelly drawn.

The “Shooting”, of course, was that of King Gustavus III (r.1771-92) at a masked ball in the opera-house, Stockholm, on 16 March 1792, an event which much later prompted the opera, Un ballo in maschera, with libretto by Antonio Somma (1809-64) and music by Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901). The queen is also shown beside the king in Presentation of the Mahometan Credentials—or—The final resource of French Atheists (1793), which has the royal family facing an Ottoman ambassador cast as the “Plenipotentiary” from the infamous songs of the time: flustered, she peers through her fan at his “Credentials” doubling as a large phallus, while “Billy Pitt”, cast as a pet monkey with a tiny penis, pisses himself with fright.

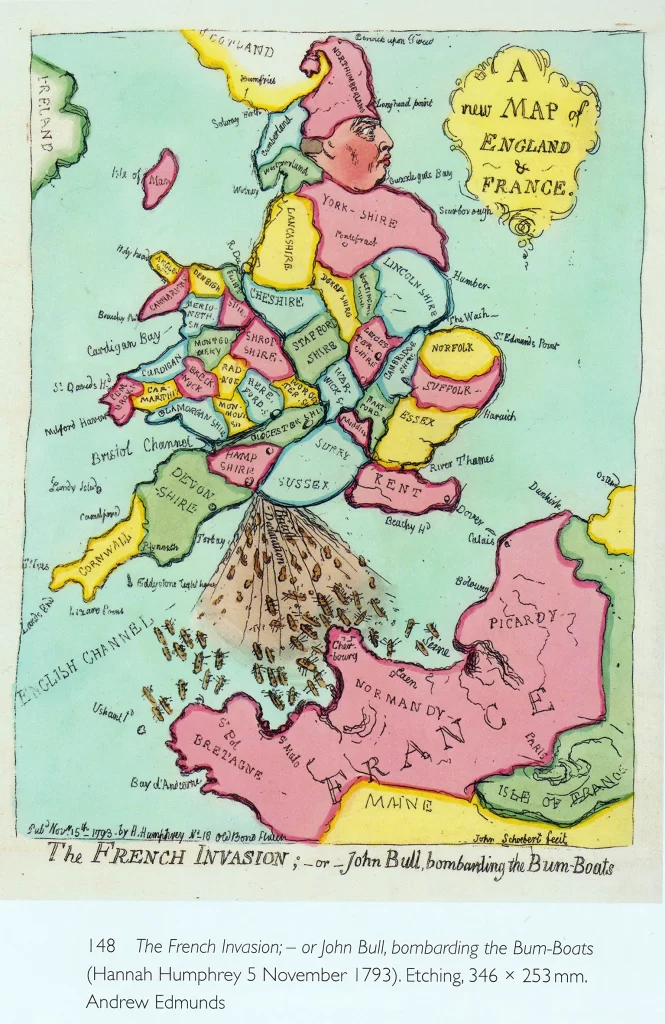

What a difference a year made, however! The tone is no longer hostile to the king and queen, and indeed in The French Invasion’—or John Bull, bombarding the Bum-Boats (1793), A new MAP of ENGLAND & FRANCE, England, divided into its counties, cast as the squatting king, shits from Portsmouth, his massive expulson of wind and turds dispelling an invasion fleet. Although in this “map”, Northumberland becomes a dunce’s cap, King George is now a national hero in the guise of John Bull, defending the realm from vile French cruelties.

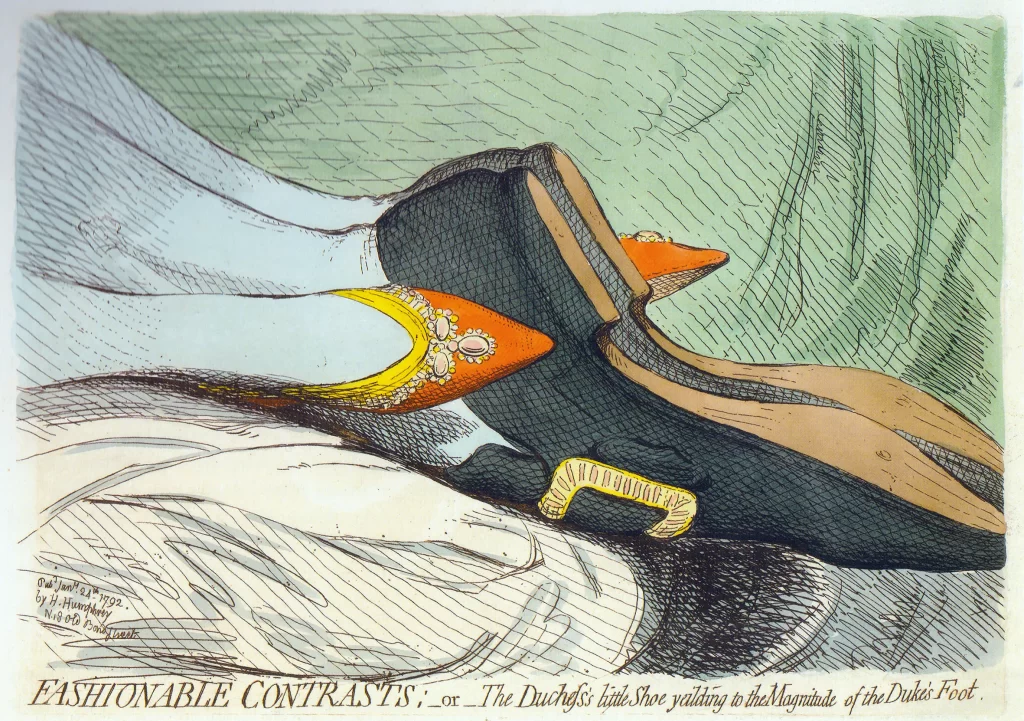

Some of Gillray’s works would pass most people by today, thanks to the much-trumpeted “world-class edication” which is nothing of the sort: one of my own favourites is his FASHIONABLE CONTRASTS;—or—The Duchefs’s little Shoe yeilding to the Magnitude of the Duke’s Foot (1792), which refers to the remarkably small hooves of Princess Frederica Charlotte Ulrica Catherina of Prussia (1767-1820), who married Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (1763-1827) in 1791: their supposed marital consummation is suggested by Gillray’s slightly indelicate rendering, in which the Duke’s very large footwear dwarfs the delicate slippers of the Duchess.

All that said, this is a fine book, beautifully and pithily written, scholarly, well-observed, and superbly illustrated, much in colour. However, it is a very large tome (290 x 248 mm), and extremely heavy, so can only be read with comfort on a table or lectern. The captions give the bare minimum of information, and it would have been far better to have had extended descriptive captions under each illustration, rather than having to root about in the text, mellifluous though that undoubtedly is.

What is perhaps the most important aspect of the book is to reveal Gillray’s significance as a propagandist in time of war, for the images he produced concerning the excesses of what had occurred in France helped to stiffen national resolve to resist the revolutionaries and defeat them and their successor, Napoléon, whose own model for a new Europe was in itself profoundly revolutionary. What he would have made of the present gang of British politicians must remain agreeable speculation.

First published in The Critic.

One Response

Good to know that there is a new book on Gillray — an artist in possession of superb draftsmanship and exquisite printmaking technique, and whose subject matter is rooted in deep understanding of England’s literary and political culture and history. Yes, he is often exquisitely cruel to his victims — but that’s what caricature at its best (of which Gillray was a master par excellence) is all about!. This sounds like a splendid publication. Thanks for alerting me to it — I’ll have to get it!