by Adam Selene

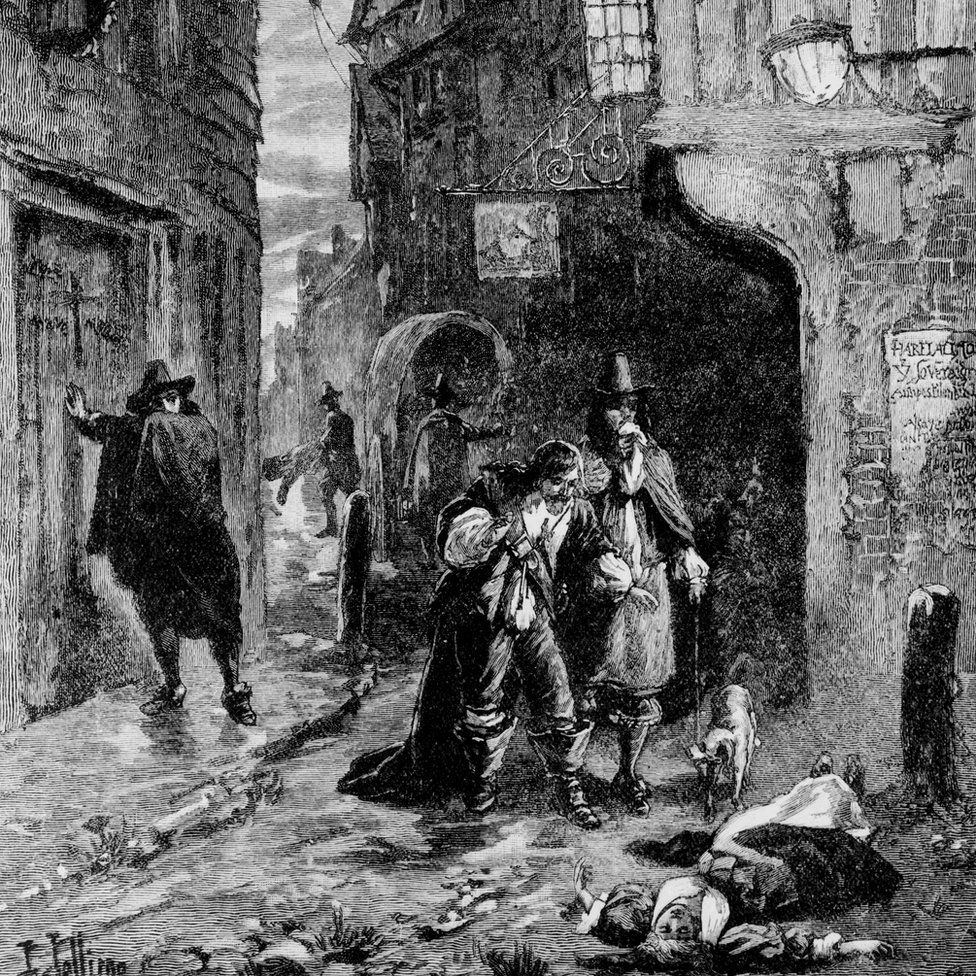

The plague struck London in 1665, devastating the city. Documented in a harrowing, yet highly readable account by Daniel Dafoe in his Journal of the Plague Year it includes lessons for “posterity.”

The outbreak began when two men died of the plague in Long Acre, to the west of the City of London, in December 1664. It was believed to have come from Holland. It began slowly, with no further deaths of plague until 12 February 1665, all in the same area. Even by May, there were only scores of deaths each week, and still confined the West End. There were none in the City itself, nor in the East End, nor across the Thames in Southwark.

By May, wealthier residents were packing up and leaving London; the King and court moved to Oxford. Dafoe weighs up whether or not to leave. He has a saddlery business, with a shop and a warehouse, and worries about the security of his goods and property. His brother was decidedly for leaving, telling Dafoe “that the best preparation for the plague was to run away from it”. But Dafoe wants for a horse, and then his servant, who he intended then to travel with on foot, abandons him. Dafoe remains in London, at his home in Aldgate, though he does venture out, including to check on his brother’s house.

In June, the Lord Mayor of London acts to stem the spread of the infection, issuing orders under an Act of Parliament passed during an earlier plague in 1603. Of these extensive orders, I will mention the appointment of examiners to inquire at houses etc whether people are sick of the plague, and if so, to order that the house be shut up, with watchmen to guard it, one during the day, and another at night. The master of each house etc, was also to report within two hours any presence of the plague, and this too would trigger the shutting up of the house, and the appointment of watchmen. A house shut up was painted with a red cross and nobody was allowed out.

The shutting up of houses was unpopular and many complaints were made about it, for “confining the sound in the same house with the sick was counted very terrible.” Perhaps only one in five who got the plague recovered. To be shut up in a house with the plague was a death sentence. It drove people to escape. Watchmen were expected to perform errands for the residents of a house shut up and when so engaged were expected to lock the door. However, people could and did escape while watchmen were away, especially at night, and watchmen were also bribed. When a person in a house showed signs of the disease, especially if it was a maid or other servant, the master of the house might vacate the property with his family and other members of the household before reporting it, leaving only the sick and perhaps a nurse to be shut up in the house. And, since reporting resulted in a house being shut up, there was a disincentive to report. Dafoe believed “that the shutting up houses thus by force, and restraining, or rather imprisoning, people in their own houses, … was of little or no service in the whole. Nay, I am of opinion it was rather hurtful, having forced those desperate people to wander abroad with the plague upon them, who would otherwise have died quietly in their beds.”

Yet, there was nothing for it but isolation. Dafoe warns posterity “that it was not the sick people only from whom the plague was immediately received by others that were sound, but the well.” He explains that:

By the sick people I mean those who were known to be sick, … these everybody could beware of; they were either in their beds or in such condition as could not be concealed.

By the well I mean such as had received the contagion, …, yet did not show the consequences of it in their countenances: nay, even were not sensible of it themselves, as many were not for several days. These breathed death in every place, and upon everybody who came near them; nay, their very clothes retained the infection, their hands would infect the things they touched…

These were the dangerous people; these were the people of whom the well people ought to have been afraid; but then, on the other side, it was impossible to know them.

There was no cure, and desperate people fell prey to:

… quacks and mountebanks, and every practising old woman, for medicines and remedies; storing themselves with such multitudes of pills, potions, and preservatives, as they were called, that they not only spent their money but even poisoned themselves beforehand for fear of the poison of the infection; and prepared their bodies for the plague, instead of preserving them against it.”

Another madness, which Dafoe counts as worse,

was in wearing charms, philtres, exorcisms, amulets, and I know not what preparations, to fortify the body with them against the plague; as if the plague was … to be kept off with crossings, signs of the zodiac, papers tied up with so many knots, and certain words or figures written on them, as particularly the word Abracadabra,…

How the poor people found the insufficiency of those things, and how many of them were afterwards carried away in the dead-carts and thrown into the common graves of every parish with these hellish charms and trumpery hanging about their necks, remains to be spoken of as we go along.

Even by June, as the plague was in the West End each week taking 3,000 to their deaths, the East End and Southwark remained relatively free of it. This, says Dafoe, made the people from those parts

… so secure, and flatter themselves so much with the plague’s going off without reaching them, that they took no care either to fly into the country or shut themselves up. Nay, so far were they from stirring that they rather received their friends and relations from the city into their houses, and several from other places really took sanctuary in that part of the town as a Place of safety, and as a place which they thought God would pass over, and not visit as the rest was visited.

The plague raged most fiercely in September, having spread by then to the whole city, and across the Thames, taking each week more than 8,000 Londoners to their deaths. It had also spread to the major cities and towns beyond London.

It remains then, for Dafoe to say something about the plague’s merciful abatement.

The last week in September, the plague being come to its crisis, its fury began to assuage. I remember my friend Dr Heath, coming to see me the week before, told me he was sure that the violence of it would assuage in a few days; but when I saw the weekly bill of that week, which was the highest of the whole year, being 8297 of all diseases, I upbraided him with it, and asked him what he had made his judgement from… ‘Look you,’ says he, ‘by the number which are at this time sick and infected, there should have been twenty thousand dead the last week instead of eight thousand, if the inveterate mortal contagion had been as it was two weeks ago; for then it ordinarily killed in two or three days, now not under eight or ten; and then not above one in five recovered, whereas I have observed that now not above two in five miscarry. And, observe it from me, the next bill will decrease, and you will see many more people recover than used to do; for though a vast multitude are now everywhere infected, and as many every day fall sick, yet there will not so many die as there did, for the malignity of the distemper is abated’… and accordingly so it was, for the next week being, as I said, the last in September, the bill decreased almost two thousand.

By the end of October, deaths were down to 1,200 a week in London, and “it was seen plainly that … the malignity of the disease abated.” But this relief brought on a new complacency

… that the distemper was not so catching as formerly, and that if it was catched it was not so mortal, and seeing abundance of people who really fell sick recover again daily, they took to such a precipitant courage, and grew so entirely regardless of themselves and of the infection, that they made no more of the plague than of an ordinary fever, nor indeed so much. They not only went boldly into company with those who had tumours and carbuncles upon them that were running, and consequently contagious, but ate and drank with them, nay, into their houses to visit them, and even, as I was told, into their very chambers where they lay sick.

… as this notion ran like lightning through the city, and people’s heads were possessed with it, even as soon as the first great decrease in the bills appeared, we found that the two next bills did not decrease in proportion; the reason I take to be the people’s running so rashly into danger, giving up all their former cautions and care, and all the shyness which they used to practise, depending that the sickness would not reach them—or that if it did, they should not die.

The doctors vehemently opposed this thoughtlessness and had directions posted across the city advising people to continue what we now call ‘social distancing’ and caution, and terrifying them with the danger of a relapse, but all to no purpose. The audacious people

… were so possessed with the first joy and so surprised with the satisfaction of seeing a vast decrease in the weekly bills, that they were impenetrable by any new terrors, and would not be persuaded but that the bitterness of death was past; … they opened shops, went about streets, did business, and conversed with anybody that came in their way to converse with, whether with business or without, neither inquiring of their health or so much as being apprehensive of any danger from them, though they knew them not to be sound.

This imprudent, rash conduct cost a great many their lives who had with great care and caution shut themselves up and kept retired, as it were, from all mankind, and … been preserved through all the heat of that infection.

Nevertheless, “most of those that had fallen sick recovered, the health of the city began to return … and wonderful it was to see how populous the city was again all on a sudden, so that a stranger could not miss the numbers that were lost.” The King and his court returned to London from Oxford after Christmas and by February 1666, “we reckoned the distemper quite ceased…” The plague of 1665 is thought to have killed 100,000 Londoners, about a quarter of the population.

Dafoe wishes he could say that being delivered of the plague improved people’s character, but reports this was far from the case, and that many said morals declined and people “were more wicked and more stupid, more bold and hardened, in their vices and immoralities than they were before…” Political and religious disagreements and point scoring resumed as before.

Dafoe finally also considers the economic impact of the plague:

At the first breaking out of the infection there was, as it is easy to suppose, a very great fright among the people, and consequently a general stop of trade, except in provisions and necessaries of life…

It pleased God to send a very plentiful year of corn and fruit, but not of hay or grass—by which means bread was cheap, by reason of the plenty of corn. Flesh was cheap, by reason of the scarcity of grass…

… Foreign exportation being stopped or at least very much interrupted and rendered difficult, a general stop of all those manufactures followed of course which were usually brought for exportation…

… what was still worse, all intercourse of trade for home consumption of manufactures, especially those which usually circulated through the Londoner’s hands, was stopped at once, the trade of the city being stopped.

All kinds of handicrafts in the city, &c., tradesmen and mechanics, were … out of employ; and this occasioned the putting-off and dismissing an innumerable number of journeymen and workmen of all sorts, seeing nothing was done relating to such trades but what might be said to be absolutely necessary.

This caused the multitude of single people in London to be unprovided for, as also families whose living depended upon the labour of the heads of those families; … and I must confess it is for the honour of the city of London, … that they were able to supply with charitable provision the wants of so many thousands of those as afterwards fell sick and were distressed: so that it may be safely averred that nobody perished for want, at least that the magistrates had any notice given them of.

This stagnation of our manufacturing trade in the country would have put the people there to much greater difficulties, but that the master-workmen, clothiers and others, to the uttermost of their stocks and strength, kept on making their goods to keep the poor at work… But as none but those masters that were rich could do thus, and that many were poor and not able, … the poor were pinched all over England by the calamity of the city of London only.

With the passing of the plague, Dafoe reports that full amends were made by another terrible calamity – the Great Fire that consumed the City of London in 1666. So much was destroyed that incredible trade was made to restore what was lost, and to supply export markets too that had been deprived of English goods during the plague, so that

… there never was known such a trade all over England for the time as was in the first seven years after the plague, and after the fire of London.

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

One Response

Defoe was 6 years old in 1666. Not a first-hand account.