Facing Future Wars: Ancient Lessons on Strategy for President Trump

by Louis René Beres

“For by wise counsel, thou shalt make thy war.” (Proverbs)

President Trump comes into office with a clear determination to “win” all ongoing and future American wars. Nothing unusual about this. After all, such determination seems plainly ordinary, traditional, even indisputable.

Upon closer reflection, however, it becomes evident that the standard criteria of victory and defeat may already have become effectively meaningless in certain expected strategic circumstances, and also that there are some important lessons to be learned about this significant transformation from the ancient world.

More precisely, therefore, here is what the new President needs to understand. Whether the United States will ultimately “win” or “lose” in current theaters of military operation, or in any other future arenas of conflict, the core vulnerability of American cities to both mass-destruction terrorism and ballistic missile attack could plausibly remain unaffected. Already, major Jihadist training and planning areas are shifting to include such far-flung places as Mali, Sudan, Bangladesh, Yemen, and even Chechnya.

Shall Mr. Trump plan to send US forces there as well, in order to “win?”

In part, at least, the times have changed with regard to the security implications of any conceivable military victory or defeat. At Thermopylae, we may learn from Herodotus, the Greeks suffered a stunning defeat in 480 BCE. What happened next is a conceptual “benchmark” for understanding where we are today. It should be duly noted by our senior military policy planners.

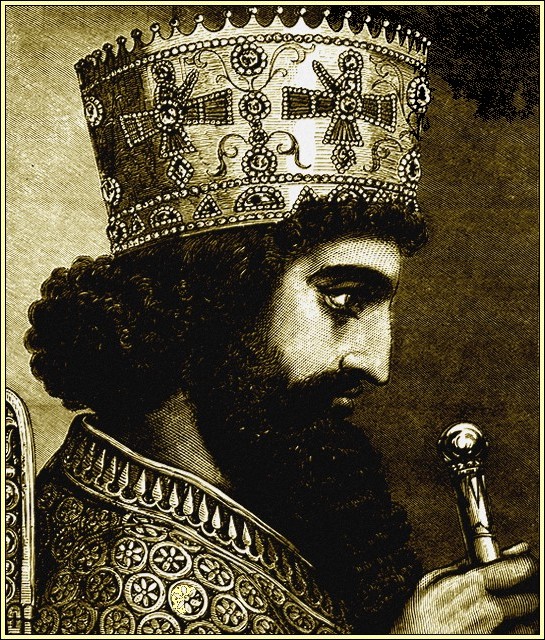

Then, Persian King Xerxes could not even begin to contemplate the destruction of Athens until he had first secured a decisive military victory. Only after the Persian defeat of Spartan King Leonidas, and his defending forces, could the Athenians be forced to abandon Attica. Transporting themselves to the island of Salamis, the Greeks would then bear tragic witness to the Persians triumphantly burning their houses, and destroying their temples.

Why should this ancient Greek tragedy still be meaningful for our new president and his advisors? Here is the chief answer. Until the actual onset of our nuclear era, states, city-states, and empires were essentially safe from homeland destruction unless their armies had already been defeated. To be sure, some national homeland vulnerabilities arose even earlier together with air power and air war, but these would generally still require “official” penetrations by a national enemy air force.

Before 1945, in war, a capacity to destroy had always required an antecedent capacity to win. Without a prior victory, intended aggressions could never really amount to much more than expressions of military intentions. Moreover, in August 1945, a non-aggressor United States was able to inflict absolutely unimaginable nuclear destruction upon Japanese civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki without first defeating the Japanese armed forces.

Indeed, bringing about such a final military defeat was precisely the consuming rationale of these two atomic strikes. Then, in a stark inversion of what had been sought at Thermopylae, the American objective had been to kill large numbers of enemy noncombatants in order to effectively prod the surrender of Japanese armies.

In essence, from the standpoint of ensuring any one state’s national survival, the “classical” goal of defeating an enemy army and preventing a military defeat has already become a secondary objective. After all, what can be the cumulative benefits of waging a “successful” war if the pertinent enemy should still maintain an effectively undiminished capacity to harm? In this connection, a consequential enemy of the United States today could be a state, a sub-state terror group, or myriad forms of a “hybrid” (state, sub-state) coalition.

For President Trump and his defense planners, the deeply complex strategic implications of this genuinely transforming development – a revolutionary development in warfare – are tangibly far-reaching, and thus manifestly worth examining. Intellectually, any such examination must always proceed dialectically, according to principles of reasoning first unraveled by Plato in Philebus, Phaedo, and the Republic. Accordingly, the task here is to ask and answer key questions, continuously, unhesitatingly, through thesis and antithesis, to an always-tentative but still needed “solution.”

Now, back to ancient history, from ancient philosophy. After suppressing revolts in Egypt and Babylonia, Xerxes was finally able to prepare for the conquest of Greece. In 480 B.C.E., the Greeks decided to make their final defense at Thermopylae. This specific site was chosen because it offered what modern military commanders would call “good ground.”

This was a narrow pass between cliffs and the sea, a geographically reassuring place where relatively small numbers of resolute troops could presumably hold back a very large army. For a time, Leonidas, the Spartan king, was able to defend the pass with only about 7000 men (including some 300 Spartans). But in the end, by August, Thermopylae had become the site of a great and distinctly memorable Persian victory.

For those countries currently in the crosshairs of a determined Jihad, and this includes the United States, Israel, and at least certain major states of Europe, there is no real need to worry about suffering a contemporary Thermopylae. There is, however, considerable irony to such an alleged “freedom from worry.” After all, from our present American vantage point, preventing any form of classical military defeat can no longer assure our safety from either mega-aggression or mega-terrorism.

This means, inter alia, that the United States might now be perfectly capable of warding off any calculable defeat of its military forces, and perhaps even of winning some more-or-less identifiable military victories, but in the end, may still have to face extensive or even existential harms.

Ultimately, Mr. Trump’s senior defense planners must inquire, what does this mean for our principal enemies? From this adversarial point of view, it is no longer necessary to actually win any war, or – in fact – to win even any particular military engagement. Our enemies needn’t necessarily figure out complex land or naval warfare strategies; in the main, they likely well understand, they don’t have to triumph at “Thermopylae” in order to burn “Athens.”

For our most focused enemies – state, sub-state and hybrid – there is really no longer any reason to work out what armies typically call “force multipliers,” or to calculate any optimal “correlation of forces.” Today, whatever our own selected “order of battle,” these disparate enemies could possibly wreak varying levels of harm upon us without first eliminating or even weakening our armies and navies. In some respects, at least, still seemingly critical war outcomes in Iraq and Afghanistan may could turn out to be largely beside the point.

What are the vital lessons of all this thinking for Mr. Trump? To date, we have not necessarily done anything wrong. Rather, our national vulnerabilities generally represent the natural by-product of constantly evolving military and terrorist technologies. We must, of course, do whatever possible to ensure that useful technological breakthroughs are regularly made on our side, but such required efforts can also carry no ironclad guarantees of perpetual success.

Rapid technological evolution in warfare can never be stopped or reversed. On the contrary, our current vulnerabilities in the absence of any prior military defeats may “simply” represent a resolute and intransigent fact of strategic life, a fully irreversible development that must soon be duly acknowledged, and then continually countered.

To ensure that these vulnerabilities remain safely below any insufferable existential threshold – by definition, an indispensable goal – the United States will soon have to refine a complex combat orthodoxy involving advanced integration of all deterrence, preemption, and war-fighting options, together with certain bold new ideas for more productive international alignments. Naturally, President Trump will also have to take a fresh and expansive look at viable arrangements for both active and passive defenses, and at all corollary and intersecting preparations for more effective cyber-defense and cyber-war.

In crucial matters of war and peace, our new president must soon acknowledge, there can be nothing more practical than a well thought out and appropriately nuanced strategic theory. Immediately, therefore, he must learn to face the stubborn fact that our always-fragile American civilization could sometime be made to suffer, and perhaps even offer a humiliating obeisance to certain significant adversaries, without first going down to any traditional forms of national military defeat. This will be a difficult lesson for us to learn, especially for President Donald J. Trump, but the alternative could cause the United States to allocate scarce military resources according to basically misconceived operational objectives.

Going forward, this sort of misallocation could prove unacceptably perilous for the United States. In facing future wars, strategic theory will be an indispensable “net.” Only an American president who chooses to “cast,” therefore, can expect to “catch.”

First published in Israel Defense