France and Islamist Terrorism

by Michael Curtis

Poise the cause in justice’s equal scales whose beam stands sure, whose rightful cause prevails.

The dilemma haunts the Western world. We want to live in a country that prides itself on being a free and modern democracy but we may be troubled by questions of whether to adhere to absolute standards of freedom. The question is pertinent at a moment when a court case in Paris began on September 2, 2020 to render justice concerning a series of painful events, terrorist attacks, in recent French history.

Islamist terrorism is like Covid-19; it is a manifestation of hatred and evil. It is able to mutate, change appearance, and continue its ruthless crusade. The fight against that terrorism and the pandemic is a major priority of civilized societies. However, the fight also relates to a number of controversial issues: the centrality of free speech and expression in democratic countries; the opportunity to express differences of opinion without using violence; the ability to utter blasphemies as well as maintain freedom of conscience; and the problem of coexistence in a multi-religious and multi-ethnic society. At the core is the issue of whether in a democratic society, the essential freedom of expression, protected by the 1789 Declaration of Human and Civil Rights, is or should be absolute because of the challenging other imperatives.

The court case in Paris is occurring after five years of investigation and delay, partly due to Covid-19, that caused the closing of most French courthouses, on September 2, 2020 with the trial of 14 suspects, three in abstentia, accused of being connected with those responsible for the terror attacks on the satirical weekly magazine Charlie Hebdo in central Paris and following events, the attack on a kosher supermarket, Hypercasher, in east Paris and other sites for three days beginning on January 7, 2015. The suspects are charged with being involved in the logistics, preparation of the events, helping finance and providing operational materials, and weapons in support of the jihadists. Because of its unusual nature, and the judicial and political importance of the trial, which is expected to last two months, the high security proceedings is to be filmed.

This case is important not only in itself but also because of its relevance in the ongoing highly controversial debate on the limits to freedom of speech, and the importance of intellectual and cultural freedom.

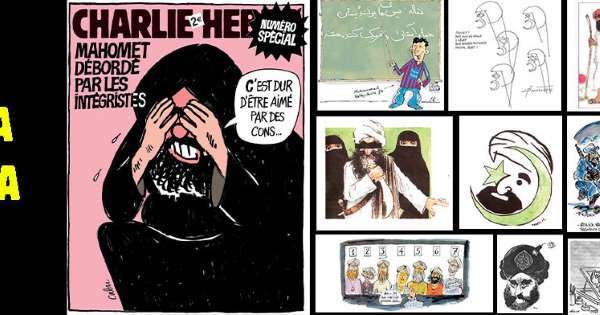

The magazine Charlie Hebdo has been a beacon of free speech in France. It is an equal opportunity offender, satirizing public figures, religious symbols, and ideas of all kinds. The terrorist attacks, the subject of the Paris trial, began as a result of Islamist opposition on the grounds of blasphemy to the publications by Charlie Hebdo that on February 9, 2006 republished 12 satirical cartoons. The cartoons were originally published by the Danish daily Jyllands-Posten in 2005, titled The Face of Mohammed, some of which were deliberately provocative. Muslim authorities regarded them as insulting, especially one that portrayed the Prophet with a bomb in his turban. In general, many Muslims consider a portrait of the Prophet as sacrilegious and thus were offended by the cartoons.

In 2007 the Grand Mosque of Paris brought criminal proceedings against CH, under France’s hate speech laws, but the Paris court acquitted the magazine finding the magazine had ridiculed fundamentalists, not Muslims as a whole. At the time, President Jacques Chirac condemned the cartoons as publications that could hurt the convictions, in particular religious convictions, of others.

But this court decision did not prevent violence. In November 2011 the office of CH in the 20th arrondissement was firebombed. Going beyond peaceful protest, two brothers, Kouachi brothers, of Algerian descent, armed with Kalashnikovs and rocket launchers, attacked the office of CH, killing 12 people, the editor, journalise and cartoonists, and a police officer outside the building. The killers shouted Allahu Akbar, God is great, and claimed they were part of an al- Quada group. They proclaimed, “we have killed Charlie Hebdo. We have taken revenge for the sake of Prophet Mohammed.

Three days later another terrorist, Amedy Couibaly. a friend of the Kouachis, pledged to ISIS and the Yemen based al Qaeda in the Arabian peninsula. attacked the kosher supermarket in east Paris shooting four Jews and a female police officer. He was assisted by a woman Hayat Boumeddiene who fled via Turkey to Syria. One of those on trial in Paris in abstentia, she is regarded by police as armed and extremely dangerous. The attack on the kosher supermarket was an indication that Jews were the main target of Islamist extremists, three year after the attack, in March 2012, on the Jewish school in Toulouse when three children and their teacher were shot dead by a .45 caliber gun and a 9 mm gun that jammed.

At the core of the events concerning Charlie Hebdo is a courageous figure, Flemming Rose, then cultural editor of the Danish paper and the person principally responsible for the decision to publish. He was prepared to defend free speech in all its forms,and risked his life to do so. Al Qaeda put him on its hit list. Rose has always refused to apologize for publishing the cartoons. He explained in an article of February 19, 2006 that he had commissioned the cartoons in response to several incidents of self-censorship in Europe caused by increasing fears and feelings of intimidation in dealing with issues relating to Islam. His goal was simply to reduce or end self-imposed limits of expression. His argument is highly relevant today. Some in the political left in Europe have been unwilling to confront the racist ideology of Islamists. They mistakenly view the Koran as a new version of Das Kapital and continue to see the Muslims of Europe as the new proletariat.

The terrorist events had a double impact. One was an outpouring of sympathy for CH with large peaceful demonstrations in France and abroad, one in Paris attended by Francois Hollande, Angela Merkel and David Cameron. Pencils were held up by demonstrators to indicate support for freedom of expression. For a moment the magic words ,”Je suis Charlie.” were carried on signs and on clothing to show international support. In its honor a street name in Paris was changed to “Place de la Liberte d’Expression.” President Hollande sent troops into the streets to guard sites.

The other impact was further attacks in France, especially a series of coordinated terrorist attacks in Paris and suburb. The most brazen were outside the Stade de France, the sports stadium in Saint Denis outside of Paris, during a football game between France and Germany at which President Hollande was in attendance, followed by mass shootings at cafes and restaurants, and then on November 13, 2015 an attack, the deadliest since World War II, at the Bataclan theater in the 11th arrondissement, preciously owned by a Jewish family, when 130 were killed and many more injured. The Islamic State of Iraq and Levant, !SIL, claimed responsibility.

The terrorist killers are alleged to have shouted, “we have killed Charlie Hebdo, we have taken revenge for the sake of the Prophet Mohammed.” But they are mistaken. Charlie Hebdo remains published. It again courageously published in its current September issue a dozen cartoons first published in Denmark in 2005, and bravely asserts. “we will never lie down, we will never give up.” However, caution is necessary. CH is published under conditions of absolute secrecy, in a secret location; the staff is surrounded by armed guards and security measures, special doors, and code words are used, and the journalists are threatened with death.

France officially recognizes that hatred still thrives in the country. In a French data base over 8,000 are listed as Islamist radicals. The wave of violence has led to 258 killed since January 7, 2015. In the midst of this reality the court in Paris must consider the basic issue. Is France the champion of free speech and expression in its publications or did the cartoons go beyond the bounds of civility and respect for others? French law states that incitement to terrorism, direct and explicit, to commit acts are punishable offences. The controversy will continue. The French Constitutional Court in June 2020 struck down provisions of a law to combat online hate speech. Perhaps the present court case will decide on the general issue of freedom. It will certainly confirm the nature of the terrorist attacks. One was against freedom of expression. The other was against Jews because they were Jews.