Globalization and the Arena of Politics

by Michael Curtis

These are the times that try human understanding. How to explain the latest political demonstrations, three consecutive nights of rioting in July 2017 by large numbers in Hamburg, Germany during and after the end of the meeting of the Group of 20, leaders of democratic countries as well as those of Russia, China, and Saudi Arabia, a group that represents 80% of the world economy? Labelled by the media as an anti-globalization or anti-capitalist or anti-establishment manifestation, it was more like a noisy performance of the fictional “Stop the world, I want to get off,” as well as an illustration of the contemporary lack of understanding of political reality.

One indication of this was that President Donald Trump was a target, though not the main one, of the protestors, purportedly against globalization. Yet, it was candidate Trump speaking in Monessen, Pennsylvania on June28, 2016 who declared that “Globalization has made the financial elite who donate to politicians very, very wealthy, but it has left millions of our workers with nothing but poverty and heartache.”

What was supposed to be a peaceful demonstration, and in fact was so in part, deteriorated into a violent clash of the estimated 50-100,000 protestors with German police resembling a contemporary Hollywood action B film. They included many young people dressed in black-clad menacing clothes demonstrating their skills in activities such as bonfires in the streets, looting of shops, firebombs, setting fire to supermarkets, Molotov cocktails, smashing of windows, damage of cars, use of iron rods, tearing up pavements to use as projectiles against the police who responded with tear gas, pepper spray, and water cannons. Several hundred were arrested or detained, while more than 200 police officers were injured.

Many of media outlets depicted the protest demonstration as if it was a serious political statement, one denoting rejection of the international political and economic status quo, specifically the ongoing process of globalization. The protestors were skilled in the use of violence against police forces, but no clear serious message emerged from their large number, a motley group of members of some 160 organizations: anti-capitalists, anarchists, environmentalists, Kurds, Scottish socialists, human rights advocates, believers in “global justice,” and automatically those hostile to the United States. With their negative battle-cries, the group can be considered aligned against corporate globalization or economic neo-liberalism, large multinational companies having political power, global trade agreements, profits made by large companies at the expense of environmental neglect, and positively for “social justice.”

The initial problem is that the Hamburg rioters and likeminded others in the US and elsewhere are rebels without a cause since they have no clear ideological position either left or right but only inadequate or irresponsible attitudes to existing complex issues. Globalization is one, perhaps the most important one at present, of those complex and difficult problems.

Since 1869 when the U.S. transcontinental railroad was completed, the US has been linked with global markets and governmental support for globalization has existed. The global depression of 1929 and the U.S. Smoot-Hawley tariff disillusioned many and impeded change, but international institutional globalization increased after World War II with the creation of the World Bank, IMF, and later World Trade Organization, OECD, NAFTA, and more recently the emergence of sovereign wealth funds from Asia and the Middle East, the state owned investment funds available from revenue from commodity exports or foreign exchange reserves.

Are the Hamburg and other protestors calling for the end of these international bodies? Certainly, a legitimate case can be made that economic globalization tends to undermine national sovereignty, and local decision making, and reduction of political and economic nationalism. In many countries there is a general retreat from, or anxiety about, multiculturalism. Today, states put up barriers to trade and people as they control resources, increase protection. These tend to make global environmental accords on the issue of climate change more difficult. Restrictions on immigration have increased, not only in Western Europe and in the U.S., but also in India, against Burmese, Argentine, against Bolivians, and in South Africa against Zimbabweans.

There are two interrelated problems in this matter. One is the absence of real alternative proposals to deal with the formidable issue of globalization. Instead there are false expectations for change and unreal ideals and then consequent disillusionment when they cannot be fulfilled. The other is that the process of politics, messy, compromise necessarily the outcome of competing interests, means disappointment for those with high expectations of policy changes.

Grandiose proposals, imaginary or dreamlike, the abolition of globalization or the “capitalist system,” cannot mask existing facts. Information technology, goods, and people are mobile across national boundaries, and new forms of information communication, especially the Internet, present problems. Western governments have had to focus on international security issues after 9/11. Nearly 80% of the world’s oil reserves are controlled by state owned firms. The world is one of movement: fast transport, mobile capital, trade deals, shift from manufacturing to services, and increase in automation. States are bound by the need for state revenue, now a growing proportion of GDP because of universal social benefits, health, social security, pensions, and public services. An increasing proportion of national income is consumed by the state.

Political systems, imperfect as they are and sometimes inefficient, incompetent, and corrupt, have to deal with these social and economic problems for which solutions are not easy. The need to govern is paramount but the present problem in many countries is the anger at present conditions, and disillusionment with established institutions and the “elite.” What results is cynicism, apathy, and even fatalism. Political leaders confront the positing of unreal ideals and promises that cannot be fulfilled in a world of complex issues, as well as the presence of competing groups which make the public interest difficult to discern. A healthy system requires, on one hand, restraint on public expectations, and, on the other hand, restrictions on political promises that cannot be delivered; on both sides what is essential is willingness to compromise.

Politicians, by the nature of their trade must seek popular support yet are likely to be unpopular since they cannot fulfill the expectations of voters. Their task is made more difficult since the mainstream media, especially TV networks, interested in sound bites and constant negative reporting, tends to stress failure and crisis more than success..

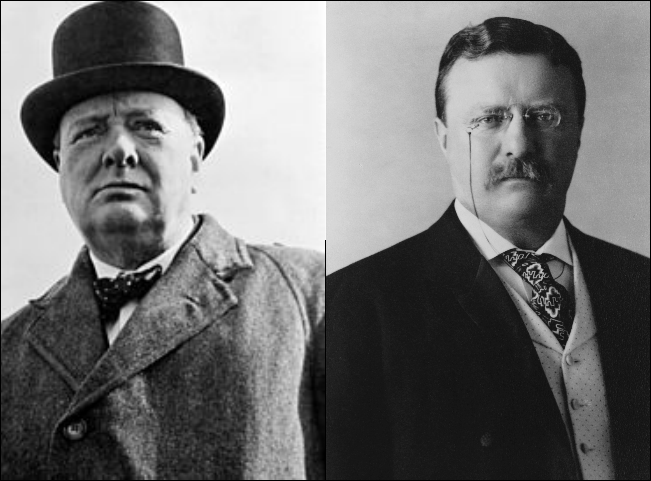

But politics is essential. It is worth going back to a fount of wisdom now appropriate to present day behavior regarding politics. Theodore Roosevelt spoke on Citizenship in a Republic at the Sorbonne, Paris on April 23,1910. He argued that “it is not the critic who counts, not the person who points out how the strong man stumbles or where the doer of deeds could have done better. The credit belongs to the person who is actually in the arena, who face is marred by dust and sweat and blood (thirty years before Winston Churchill used the same imagery during World War II), but who does actually strives to do the deeds… so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

The answer to the Hamburg and other protestors can only come from those who are prepared to be in the arena and are willing to quell the storm and ride the thunder. They should act on the basis of ideals, but not on those that are so high that they are impossible to realize.