Roger Bowdler reviews James Stevens Curl’s new book on English Victorian Churches in The Critic.

A distinguished and prolific architectural historian, Curl is a rare critic these days. Unafraid to express his views about the baleful influence of modernism on the built environment, and forthright in his assessments, he pulls no punches in his jeremiads. Curl seeks consolation in exploring the architecture of bygone times. You can imagine him in a world beyond, going head to head with the Victorian architects covered in this book, arguing about liturgy and architectural precedents with equal force, and drawing on a deep well of understanding as he does so.

We are enmeshed in identity politics; Victorians were knee-deep in religious dispute. Forms of worship mattered deeply. Parliament legislated on ritual, and the degrees to which the pre-Reformation church was revived affected sacred architecture and church allegiance. Anglican factions are eloquently explained, and there is no doubting the author’s Anglo-Catholic allegiances. For Curl, the beauty of worship and the fittingness of liturgical setting for liturgy are of fundamental importance in understanding how and why these churches took the form they did, and in explaining what the Gothic Revival really meant.

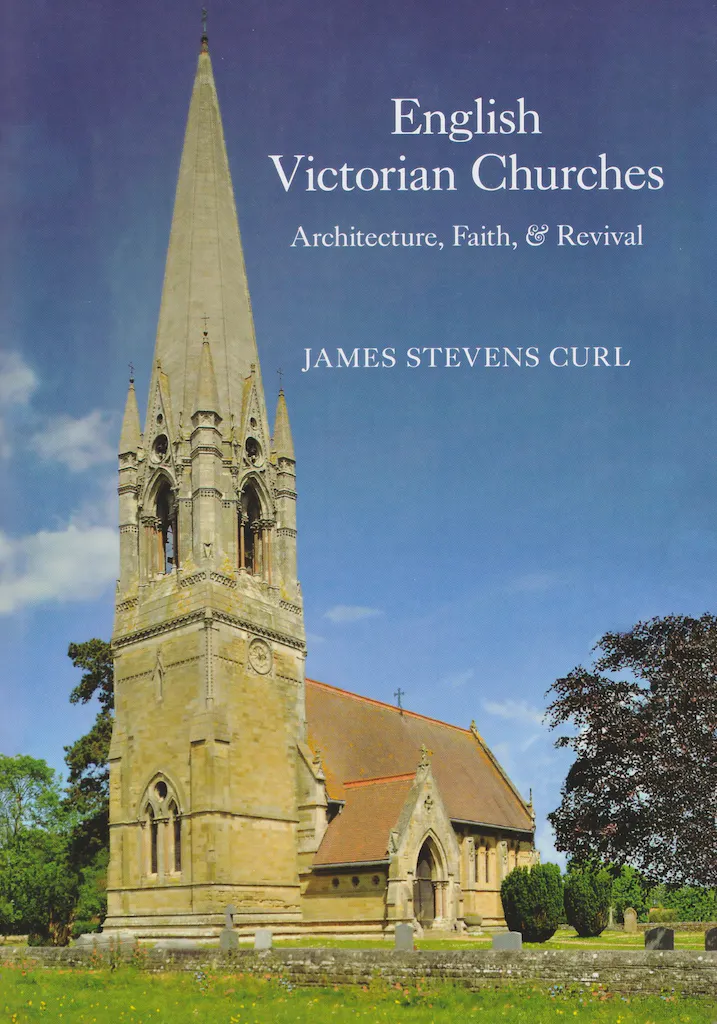

The Victorians were heroic church builders, across all denominations. There’s the rub: there are just so many of these buildings to consider, and to care for. Barry Orford’s preface sets out the dilemma: “the Victorians, riding a wave of confident, mission-minded enthusiasm, built an excessively large number of places of worship … Superfluous to requirements today, these forlorn shells invite a superficial view that Victorian work is dispensable.” Curl’s mission is to demonstrate why these buildings matter. This is his third book on the topic, and this beautifully illustrated version is very much the one to go for. It sits alongside William Whyte’s Unlocking the Church, a 2017 study of Victorian sacred space, and takes a robustly idiosyncratic line.

For many church-crawlers, it is the time-depth and accumulation of fittings inside an ancient church which brings particular delight. Norman fonts jostle with Stuart alabaster and Georgian altars. Some heritage pilgrims are biassed against Victorian churches, regarding them as mere cribbed copies of mediaeval exemplars that lack the accumulations of generations of worshippers. This book will make them think again. Pevsner comes in for regular challenge from Curl, but he was one of the experts — including Betjeman — who opened heritage eyes to the merits of the Victorian church from the 1960s.

These churches were generally built in a single go, replete with fittings, and were the product of one architectural (and liturgical) vision. The pleasures derive from this totality of effect, on the handling of space, the deployment of bold materials, the learned drawing on historic sources, and on the fittingness of such ensembles for a particular style of worship. Curl is excellent on all of these, and his eye for a continental source of inspiration is extremely sharp. The pinnacle of his praise is in his description of Butterfield’s All Saints, Margaret Street (1849–59), the “finest memorial to the Oxford Movement, glowing, noble and assured” which he intriguingly compares with the work of John Everett Millais.

Before we get to the narrative sequence of Pugin, Scott, Butterfield, Burges, Brooks, Street, Pearson, Bodley and Bentley, opening chapters chart in some detail the religious, antiquarian and doctrinal backgrounds. John Keble’s 1833 Sermon was regarded by many as the start of the Oxford Movement of religious revival. Tractarianism, the revival of interest in liturgy and doctrine, was aligned with the romantic rediscovery of mediaeval architecture: these pre-Victorian roots are examined closely.

An interest in ritual and a return to mediaeval approaches begged the question of the Church of England’s relationship with the Roman Catholic church. Fascinatingly, Victorian Catholic churches mainly relied on Italianate Baroque to signal their Ultramontane allegiance to Rome. Pugin, a passionate Catholic convert, was much more influential on Anglican architects. The “smells and bells” of High Anglican worship was seen as “Romanism” by some, and viewed with great suspicion. If there is a villain in this book, it is surely John Kensit of the Protestant Truth Society (established 1890), which delighted in disrupting High Church ritual. Curl avoids telling us that Kensit was eventually felled in 1902 by a chisel, hurled at him by a foe of his fundamentalist intolerance at a rally in Birkenhead.

This is an enriching read, replete with a full glossary (including pocket essays on “Gothic” and “Gothic Revival”) and excellent illustrations. It’s worth singling out the physical qualities of this book, too. In an age in which limp and drear print-on-demand books become ever more common, this carefully designed and well-made volume is a pleasure.

If I have a beef with this book, it is in its pessimism. To read it, one would imagine these great places of worship were being toppled on a regular basis, and their fittings heedlessly disposed of. Au contraire: the Church of England has an effective system of control through the faculty system, and diocesan advisory committees exist to advise; the Victorian Society and Historic England have their say, and many of the churches covered in this book are listed in the highest grades. Not that the picture is not all rosy: congregations dwindle, liturgical changes don’t go away, and repair costs soar. Curl’s very personal tribute to the Victorian Age of Faith explains much about the zeal behind their creation, and reminds us to care for them.