How to be a PC creep

by Theodore Dalrymple

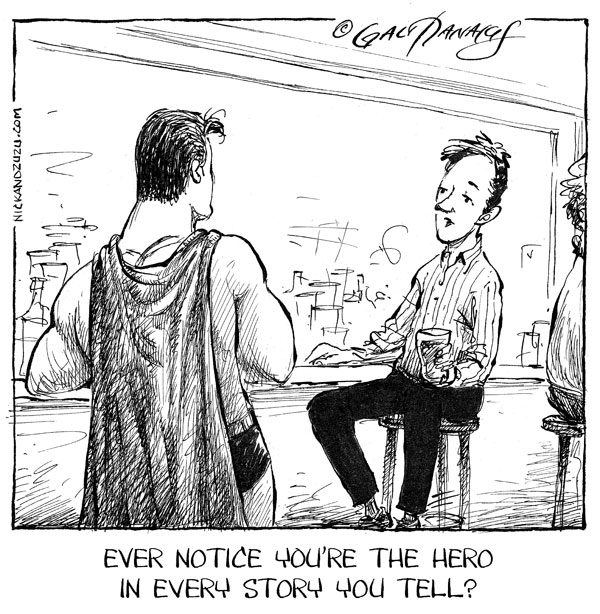

There was a time in my life, many years ago, when people were not expected to boast about their accomplishments: indeed, they were expected not to boast about their accomplishments. Self-praise was regarded as no praise; indeed, someone who praised himself was thought to be a bad character.

These days, however, boasting and the expression of self-satisfaction are essential to getting on in life, to climbing a hierarchy, in medicine as elsewhere. You have to recommend yourself, not wait to be recommended by others (which might never happen); you must hide a bushel under your light.

Recently I went through a pile of last year’s British Medical Journal that had been reproaching me, unread, in my study. They all contained an interview with a doctor, in the course of most of which the interviewee is asked to summarise his or her own personality in three words. In my opinion, this is a question that should not have been asked, indeed that is almost obscene, being an invitation either to self-congratulation or to arch self-deprecation, the higher and slightly more acceptable form of self-congratulation. To adapt slightly the final sentence of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus, whereof one ought not to speak, thereof one ought to be silent.

The answers given to the question were for the most part odious, and not even odious in an interesting way: they spoke of a dull flat hinterland of political correctness. They said they were:

Energetic, enthusiastic and dedicated;

Happy, enthusiastic and committed;

Honest, fair and compassionate;

Energetic, determined and compassionate.

One had the depressing feeling that the interviewers had been given, and accepted, a buzzword generator of self-praise: no one demurred, no one was, for example, bad-tempered, mean-spirited or egoistic. There wasn’t even a gossip among them, let alone a writer of poison-pen letters. Perhaps they were all of the things that they said they were, but one could not help wishing that it was someone else who said it of them; moreover, they made ditch-water seem like champagne.

Interestingly, and perhaps significantly, the only answer that broke the mould came from a man who was described as the oldest active researcher, at 104 years (he had worked with Alexander Fleming), in Britain. He said of himself that he was lucky, long-lived and loquacious: an answer much superior in every way, including the literary, to that given by those who were a third his age. Could this tell us something about the changes we have wrought?

First published in Salisbury Review.