Humor is no Laughing Matter

by Michael Curtis

In France, a society with sharp divisions over race, gender, and religion, three comic spy movies has led to an intense debate over what is supposed to be funny. In general, humor is both a source of entertainment and a means of coping with the difficult and unpleasant encounters and stressful events of life. Humor is laughter, but can also pertain to and reflect on serious subjects. What makes us laugh? Events today indicate that some humor of the past is no longer funny as society values, ethical beliefs, religious affiliation, have changed with mutating culture, age, and political orientation.

At the center are two literary devices, satire and parody, linguistically distinct, but sometimes difficult to distinguish. Satire uses devices, irony, exaggeration or understatement, euphemism, to illustrate or ridicule the faults in society. It has been admired throughout history, but has also been subject to censorship with its authors often subjected to humiliation. Imprisonment, and assassination. Yet the tradition of satirical commentary has lasted at least since Juvenal in the 1st century AD who denounced contemporary persons and institutions, using invective, moral indignation, and ridicule, to the present day, embracing great writers such as Samuel Johnson, Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope, George Orwell, and Albert Camus. Satire is focused on undesirable social and political features, aims at challenging prejudice, bigoted remarks and behavior.

Parody is spoof or caricature commenting on or making fun of a subject by imitating the style of another product or composition in literature, music, TV or film, aiming to produce a comic effect. It is used for ridicule, but also to target something. Examples flow, Charlie Chaplin mimicking Adolf Hitler in The Great Dictator, Mel Brooks mocking Nazis in The Producers, Gulliver ridiculing the idealism of knights, the heroes of romantic tales. Parody can be used to make political or philosophical points, but it can also be pointed for sharp criticism. In sonnet 130, Shakespeare wrote “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun, coral is far more red than her lips’ red.”

In modern times, satires and parodies have been plentiful and a part of public discourse in democratic countries, with utterances that mock political and religious institutions. The problem has arisen today of the degree to which the principle of free speech can protect satire and parodies regarded by part of the community as offensive. In the present cultural climate, and era of changing sensibilities, debates abound about the extent of freedom of expression regarding jokes based on ethnic and gender stereotypes.

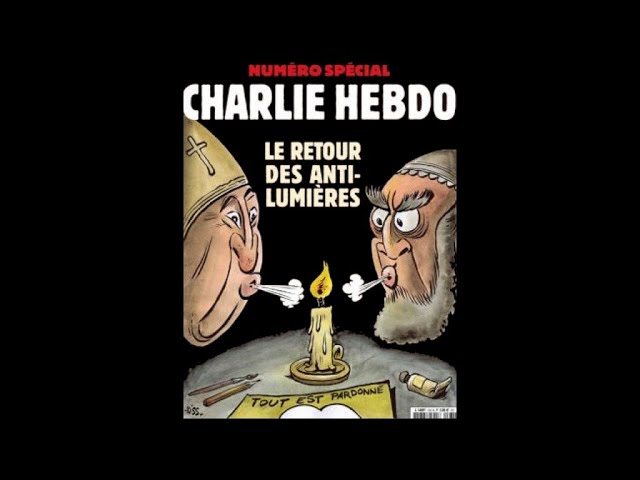

The issue of changing views may be illustrated in the case of the French satirical cartoon magazine Charlie Hebdo. Islamist terrorists on January 7, 20i5 massacred cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo who were responsible for caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad, especially one that depicted a bomb hidden in his turban. Depictions of the founder of Islam are forbidden in the Sunni branch of the faith. The cartoons were regarded by observant Muslims as blasphemous, offensive to Islam as well as in bad taste. CH became a target for fundamentalists. On the other hand, thousands supported the publications, and used the slogan, “Je suis Charlie”, in support of CH.

Have sensibilities about satires of Islam and the nature of humor changed? It is noticeable that the circulation of Charlie Hebdo has substantially declined, from 260,000 in 2015 to only 35,000 today, and may not survive. In similar fashion, the French daily satirical puppet show, Les Guignols, satirizing the political world, media, and celebrities was cancelled in 2021.

A new controversy over the dimensions of humor has broken out in France. For many years, France has been making spy movies based on the 86 books written by Jean Bruce, beginning in 1949, predating Ian Fleming’s James Bond books by four years. The first series ended in 1970s but in 2006 the series was restarted with Oscar winner Jean Dujardin in the leading role, playing an agent with the French Office of Strategic Services, in the series OSS 117.

The central figure in the three films in the series is the fictional secret agent with a ridiculous name, Hubert Bonisseur de la Bath, self-important, dim witted, politically incorrect, elitist, equal-opportunity racist offender, described as typically French. The inside joke is that this idiot-savant is played by the handsome actor, Oscar winner Dujardin, who’d win the Olympics for charm and who at times resembles the young Sean Connery. Hubert pronounces his codename, “one hundred and seventeen,” not double oh seven, a la James Bond. Indeed, he is a feasible parody of Bond, seducer of women, masculine icon, wearer of elegant attire. As a result, OSS 117, the anti-hero, became immensely popular, in the mode of nostalgic figures like Cyrano or Asterix.

The humor is pointed. OSS 117 has few principles but adheres to traditional colonial ideology, French patriotism, machismo. He is a send-up of a super spy, fumbling through his problems with fake heroism, egocentric, self-important, prejudiced, partly because of nationalist ideals and partly through ignorance. He is not intelligent as James Bond, but the films, to make the comparison evident, do use some cinematic and visual effects familiar in Bond films as well as in some in the films of Alfred Hitchcock.

Three OSS 117 films have been released: Cairo, Nest of Spies, 2006; Lost in Rio 2009; From Africa with Love 2021.

The first film, Cairo , was a satire on western ethnocentrism, a parody of the 1960s spy genre, with witty dialogue, tongue in cheek, with fun about the bad guys, ex-Nazis, Soviet brutes, French colonies. The hero’s ignorance is made clear. OSS 117 remarks about the Suez Canal view point, “your civilization today is grandiose. To build this 4,000 years ago was visionary,” to which the reply was “but the Canal was only built 86 years ago.” His view of Islam is that the muezzin calling for prayer, “seems a very strange religion but you’ll get used to it. “

In the second film, Rio, OSS 117, meeting bikini clad women, gun wielding Chinamen, “dirty Yellows,” tanned foreign agents , is a symbol of French colonial culture imperialism, with obliviousness to sensitivities of race, creed, gender, and French political reality. Women should be only mothers or secretaries. He searches for a list of Vichy collaborators, “it must be a short list.” He asks the Israeli Mossad which wants to capture and send the Nazi hiding in Argentina to Israel for his crimes, “what crimes.” In a France when Francois Mitterand was president, OSS 117 replies to the question, “What do you call a country with a military leader, a secret police, one TV station, and censorship,” OSS 117 replies “France, de Gaulle’s France.”

These two films, reasonably profitable, were not subjected to criticism for their humor, and people laughed along with them, and considered they were critical of contemporary prejudices. The anti hero is not interested in the world outside France. He is clearly prejudiced against Judaism and Islam, resistant to change.

In the just released third film, From Africa with Love, OSS 117 in the 1980s has to help the dictator in a former French colony in East Africa, black Africa, who is partner for France. The opponents of the dictator are sent to prison or are eaten by his pet leopard. He is threatened by the Soviet Union which is supplying weapons to a local group which wants to overthrow the dictator and start a coup d’etat which threatens the interests of France. The subtext is France’s well-meaning but disastrous policies in Africa. Things have changed but OSS 117 has not and is still a sympathetic idiot, acting in disarming innocence and believing in what he is doing. He believes everyone on earth wishes they were French. He gives photos of Rene Coty, then president of France, as awards, tips, or gifts. He believes the “native” has 7 or 8 children, but the native tells OSS 117 he has two, both are at university in New York. He mocks Islam throughout the film. He is sent to bring peace to the Middle East but does not know of King Farouk. He tries to avoid inappropriate remarks, and is careful not to anger friends of France, but nevertheless explains the Continent as “Africans are happy, nice, and they are good dancers.” To bone up on Africa, he reads the comic book “Tintin in the Congo,” a work generally disapproved for its racist, colonial attitude, depicting Africans as savages to be civilized by Europeans. OSS 117 is sent as reward for his efforts to Iran.

The issue is that the humor in the OSS 117 series, the return of the spy-colonialist in this era of post-colonial France, is being called in question by cultural critics, and is not funny. France had changed. In the past, humor in the films was seen as liberation or catharsis. But the series is not “liberating,” but can be seen as tasteless and insensitive. It is more difficult to laugh in a changing France, where certain freedoms of expression have been curtailed. Racist and sexist jokes may have once worked, but not now, nor is prejudice against Jews, Judaism, and Islam, or people from former French colonies acceptable, or hypocrisy by French former colonialists. France is not alone in its concern of satire and parody. What can we laugh at?

In the film Rio, the young Jewish woman says, “Jewish humor is not funny.” OSS 117 replies, “Then how can it be humor?” Should topics such as religion, sexism, racism, be addressed in a humorous manner? The problem is that satire has a double effect. It focuses on divisive topics, but it can also be misunderstood as promoting discrimination.