Inescapable Delusions

by Theodore Dalrymple

It is human nature to be fascinated by dramatic events and to invest them with more significance than they warrant. First we take them as being more typical than they are, and then we take them as the shape of things to come. We forget the wisdom of Ecclesiastes, that there is no new thing under the sun.

Once, on the small island of Jersey in the English Channel, I researched three murders that took place there within three months in the middle 1840s, including one of a policeman, when normally there was only one murder on the island every ten years. The population, not surprisingly, thought that something must have gone terminally amiss in their society for there to be so many murders in so short a time. In fact, they were just a statistical blip and the rate of murder returned to what it had always been before, and no policeman has ever been murdered on Jersey in the intervening century and three quarters.

How, then, are we to take the story of Adam Neumann, the former chief executive of WeWork? Is it just the kind of thing that will from time to time happen, or is it emblematic of a deep malaise in the economic system of the west? For myself, I incline to the latter view, but then I recall that I have long advocated as compulsory reading for all economists, bankers, stockbrokers, investors and company directors, the book by Charles Mackay in 1841, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. Whether this would do any good depends on whether people learn from other people’s experience at third or even fourth hand; the recurrence of similar mass delusions through history, even or especially among the highly-educated, experienced and well-informed, would suggest not. This time, they always tell themselves, it is different; this time money really can be conjured out of nothing.

By comparison with many an investment banker, at least those involved in the WeWork saga, people who buy lottery tickets are rational beings. Doctor Johnson once called a lottery a tax on stupidity, but here for once his humanity and understanding deserted him. Lottery tickets, bought mainly by people who, with some reason, think that they are unlikely to attain wealth or even modest prosperity by any other means, do not really expect to win and are therefore not disappointed or embittered when they do not, provide an interval of innocent and consoling daydream between the day of purchase and the day of the draw—albeit that the content of those daydreams is usually that of a leisured life with present pleasures enjoyed on a vastly larger scale, that would lead soon to bankruptcy or the hospital, or both.

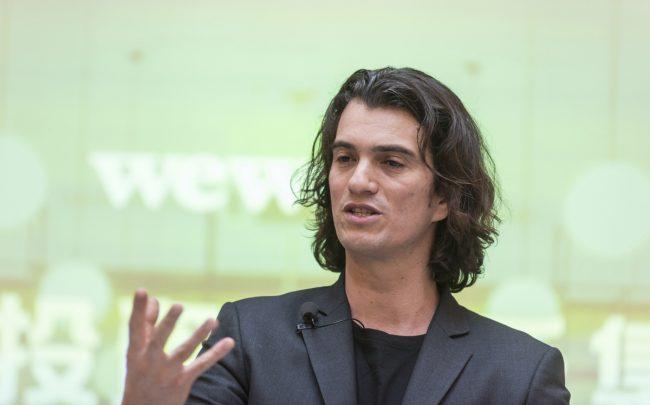

The backers of Adam Neumann had obviously not read, marked, and inwardly digested Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. With the precipitancy reminiscent of the Gadarene swine they poured billions, mainly of other people’s money, into a scheme that, fundamentally, was neither new nor exceptional, and they gave to the expression “throwing good money after bad” a new piquancy. In charge of very large companies, reputed financiers, they were dazzled by a man because he was six feet five tall, had long hair and the manner of an established rock star, though what he was proposing was as about as solidly grounded in reality as Jimmy Swaggart’s promise of eternal life if you contributed enough to his television ministry. No financial losses, no outrageous sumptuary expenditure at company expense, no evident loss of self-control on the part of the scheme’s founder, could dim their faith, at least until the evident absurdity of what they had done could no longer be disguised from the public. Men go mad in crowds, said Mackay, but they recover their senses one by one—and too late, he might have added.

From this debacle, it was reported, Mr. Neumann emerged with $1.7 billion, when $1.70 might have seemed an extravagantly generous reward for what he had done. Of course, final accounts have yet to be rendered: the misled, or swindled, are unlikely to take their losses lying down. But even if Mr. Neumann is forced, after prolonged proceedings, to disgorge (to the great profit, no doubt, of lawyers) a large proportion of what he has, for the time being, walked away with, what the public will remember is that he benefited enormously, pharaonically, from conduct that was delusional at best and grossly dishonest at worst.

Two questions arise: is the story of WeWork now typical or emblematic of—or even necessitated by—our current economic system, and what is its likely effect upon the feeling of the population, that sooner or later will translate into action?

The first question—was Mr. Neumann an outlier, or does his manner of operating tell us something essential about the way the contemporary economy works, in the West if not in China and other countries that are in the process of taking over the world?—is perhaps not susceptible of a definitive answer. After all, this is not the first time in history, not by a long way, that a charismatic charlatan has wheedled his way to wealth, in life as in fiction. The name of Ivar Kreuger, the Swedish match king, who said that the stupidity of people was the soundest basis of any business, springs to mind. Still, one cannot help thinking that in a world in which the real and the virtual are increasingly difficult for people to distinguish, susceptibility to visionary scams can only increase.

As to the effects of this episode, at least as comic as it is tragic, on the feelings of the population, one can only say that it is likely to increase or reinforce its belief that it is living under a fundamentally unjust economic dispensation which can, and ought, to be overthrown, almost irrespective of whatever succeeds it. This is a dangerous state of mind, for it renders people susceptible to the siren-song of egalitarian demagogues.

On the question of whether there are any reforms, short of a change in human nature, that can prevent future Adam Neumann’s from making fortunes, I am agnostic. A reading of Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds suggests not.

First published in the Library of Law and Liberty.