Investigators build a case for Islamic State crimes against Yazidis

From Associated Press, via the Texarkana Gazette

QASR AL-MIHRAB, Iraq — He was burly, with piercing blue eyes, and it was clear he was in charge when he entered the Galaxy, a wedding hall-turned-slave pen in the Iraqi city of Mosul. Dozens of Yazidi women and girls huddled on the floor, newly abducted by Islamic State group militants.

He walked among them, beating them at the slightest sign of resistance. At one point, he dragged a girl out of the hall by her hair, clearly picking her for himself, a Yazidi woman — who was 14 when the incident occurred in 2014 — recounted to The Associated Press.

A group of investigators with the Commission for International Justice and Accountability is amassing evidence, hoping to prosecute IS figures for crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide — including Hajji Abdullah.

“IS fighters didn’t take it upon themselves to rape these women and girls. There was a carefully executed plan to enslave, sell, and rape Yazidi women presided over by the highest levels of the IS leadership,” said Bill Wiley, executive director and founder of CIJA. “And in doing so, they were going to eradicate the Yazidi group by ensuring there were no more Yazidi children born.”

CIJA shared some of its findings with The Associated Press. The group, through IS documents and interviews with survivors and insiders, identified 49 prominent IS figures who built and managed the slave trade, as well as nearly 170 slave owners, including Western, Asian, African and Arab fighters. These also include top financiers, military commanders, local governors and women traders, many of them from the region neighboring the Yazidi community’s villages.

The AP also put together findings from IS’s own literature, along with interviews with IS members, former slaves and rescuers, to establish how slavery was strictly mapped out from the earliest days, devolving into a free-for-all with fighters enriching themselves by selling Yazidi women as the group’s power began to disintegrate.

The Islamic State group’s narrative is that slavery is a justifiable consequence of battle during its brutal capture of Sinjar, a region west of Mosul, as part of its attempt to establish a so-called caliphate. But the AP determined, based on CIJA’s investigation and its own reporting, that the highest levels of leadership were directly involved in organizing an enslavement machine that became central to the group’s structure and identity. Even as their caliphate collapsed around them, the militants made keeping their grip on slaves a priority. When slave markets proliferated out of the leadership’s reach, internal documents show IS officials struggled to impose control with a stream of edicts that were widely ignored.

When Yazidis were seized, top IS commanders registered them, photographed the women and children and categorized them into married, unmarried and girls. Initially, the thousands of captured women and children were handed out as gifts to fighters who took part in the Sinjar offensive, in line with the group’s policy on the “spoils of war.” Under early IS rules, war booty was distributed equally among the soldiers after the state took 20%, known as the “khums.”

According to survivors and CIJA, some fighters came to detention centers with pieces of paper signed by Hajji Abdullah confirming their participation in the Sinjar attack and entitling them to a slave. Women and girls also would be picked out to be raped by fighters, then returned to detention.By early 2015, the remaining women were transferred to the Syrian city of Raqqa, the caliphate’s capital, and then distributed across IS-controlled areas, CIJA and survivors of slavery accounts showed.

The IS propaganda machine was mobilized to justify its revival of slavery. Articles, sermons and fatwas interpreting Islamic law were issued outlining how taking slaves was in accordance with Islam.

IS operated centralized slave markets in Mosul, Raqqa and other cities. At the market in the Syrian city of Palmyra, women walked a runway for IS members to bid on. Others, like the one in al-Shadadi, distributed women to militants by lottery. A June 2015 notification reviewed by the AP called on IS fighters in Syria’s Homs province to register for an upcoming slave market, or “Souk al-Nakhassa,” giving those on the front lines a 10 day-notice to attend. Participants were told to enter bids in a sealed envelope.

Managing the robust system turned out to be more complicated than the leadership planned. And chaos abounded.

Slaves meant to be a reward to fighters were resold for personal profit, and some IS members made tens of thousands of dollars ransoming captives back to their families. Violence and abuse by owners led to rising reports of suicides and escapes among captives.

The CIJA archive contains a copy of an edict by the Department of War Spoils that banned separating enslaved women from their children, with a handwritten note ordering it distributed to all departments and provinces — a signal that earlier decrees had failed to stop the practice.

In July 2015, the Delegated Committee — effectively the cabinet — ordered all slave sales to be registered by Islamic courts, seeking to end sales among fighters. It also required the finance minister of each IS province to keep track of women between transactions. Captured IS militants offered a glimpse into the resistance the leadership faced in enforcing its rules. In the eyes of some in the rank-and-file, what they saw as their right under Islamic law could not be restricted.

Abu Hareth, an Iraqi IS preacher held in a Baghdad prison, told the AP that many fighters didn’t feel compelled to register sales in courts. Abdul-Rahman al-Shmary, a 24-year old Saudi who traded in slaves and is held in a Syrian Kurdish-run prison, dismissed the rules as rooted not in Islamic law but in the leadership’s need for control. “It was about power and not for God’s sake,” he said.

Laila Taloo’s 2 1/2-year ordeal in captivity underscores how IS members continually ignored the rules.

“They explained everything as permissible. They called it Islamic law. They raped women, even young girls,” said the 33-year old Taloo, who was owned by eight men, all of whom raped her. She asked that her name be used because she is publicly campaigning for justice for Yazidis.

Taloo was first sold to an Iraqi doctor, who three days later gifted her to a friend. Despite the rules mandating sales through courts, she was thrown into a world of informal slave markets run out of homes. Her third owner, an Iraqi surgeon, woke her one night and had her dress and put on makeup so four Saudi men could inspect her. One didn’t like her ankles; another, a member of the IS religious police, paid nearly $6,000 for her.That owner posted pictures of his slaves online and, every day, they were paraded before potential buyers. “It was like a fashion show. We would walk up and down a room filled with men who are checking us out,” Taloo said.

With each owner, she fought to keep her children safe. One man took photos of her then-2-year-old daughter, threatening to sell her to an Iraqi woman who couldn’t have children. IS was known to separate children from their mothers, using them as household slaves or child soldiers, changing their names and forcing them to convert to Islam.

Some 3,500 slaves have been freed from IS’ clutches in recent years, most of them ransomed by their families. But more than 2,900 Yazidis remain unaccounted for, including some 1,300 women and children, according to the Yazidi abductees office in Iraq’s Kurdish autonomous region.

Most are believed dead, but hundreds of women and children likely remain held by militants, said Bahzad Farhan and Ali Khanasouri, two Yazidis who work as rescuers tracking down the enslaved. For years, the two have followed slave markets on social media, contacting smugglers and searching out IS militants willing to ransom their captives to their families. Working separately, they have secured freedom for dozens of women and children.

At times, they said, Syrian opposition fighters have refused to return enslaved girls they come across in their territory.

One Yazidi girl, forced to convert to Islam and six months pregnant, was found in the northwest Syrian town of Azaz when fighters captured a Saudi IS militant transporting her. One of Farhan’s contacts, an opposition fighter, offered to bring the girl back to her family. But his commanders stopped the transfer. “They said, `She is now a Muslim girl, why are you sending her back to the infidels?'” Farhan said.

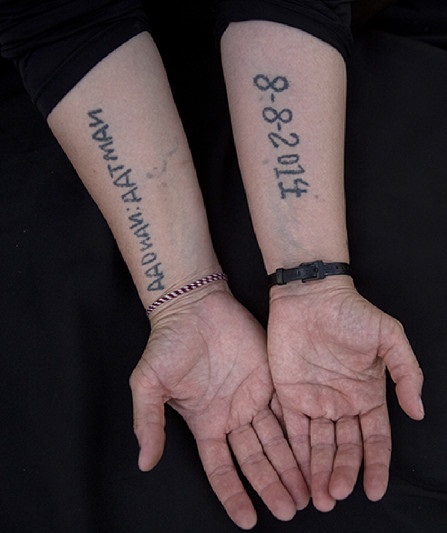

In this Thursday, Aug. 29, 2019 photo, Leila Shamo displays tattoos she made while enslaved by Islamic State militants at her home near Khanke Camp, near Dohuk, Iraq. Shamo, 34, has used her breast milk, charcoal ash and a needle to write the names of her husband, and two sons on the front of her hand and the inside of her right forearm: Kero, Aadnan, Aatman. On the inside of her left forearm, she wrote the date IS militants captured them all together: 8-8-2014. The mother of five tattooed their names and her date of capture on her skin to spite her captors and to never forget. (AP Photo/Maya Alleruzzo)

In this Thursday, Aug. 29, 2019 photo, Leila Shamo displays tattoos she made while enslaved by Islamic State militants at her home near Khanke Camp, near Dohuk, Iraq. Shamo, 34, has used her breast milk, charcoal ash and a needle to write the names of her husband, and two sons on the front of her hand and the inside of her right forearm: Kero, Aadnan, Aatman. On the inside of her left forearm, she wrote the date IS militants captured them all together: 8-8-2014. The mother of five tattooed their names and her date of capture on her skin to spite her captors and to never forget. (AP Photo/Maya Alleruzzo)