Making Book on Trump

by Bruce Bawer

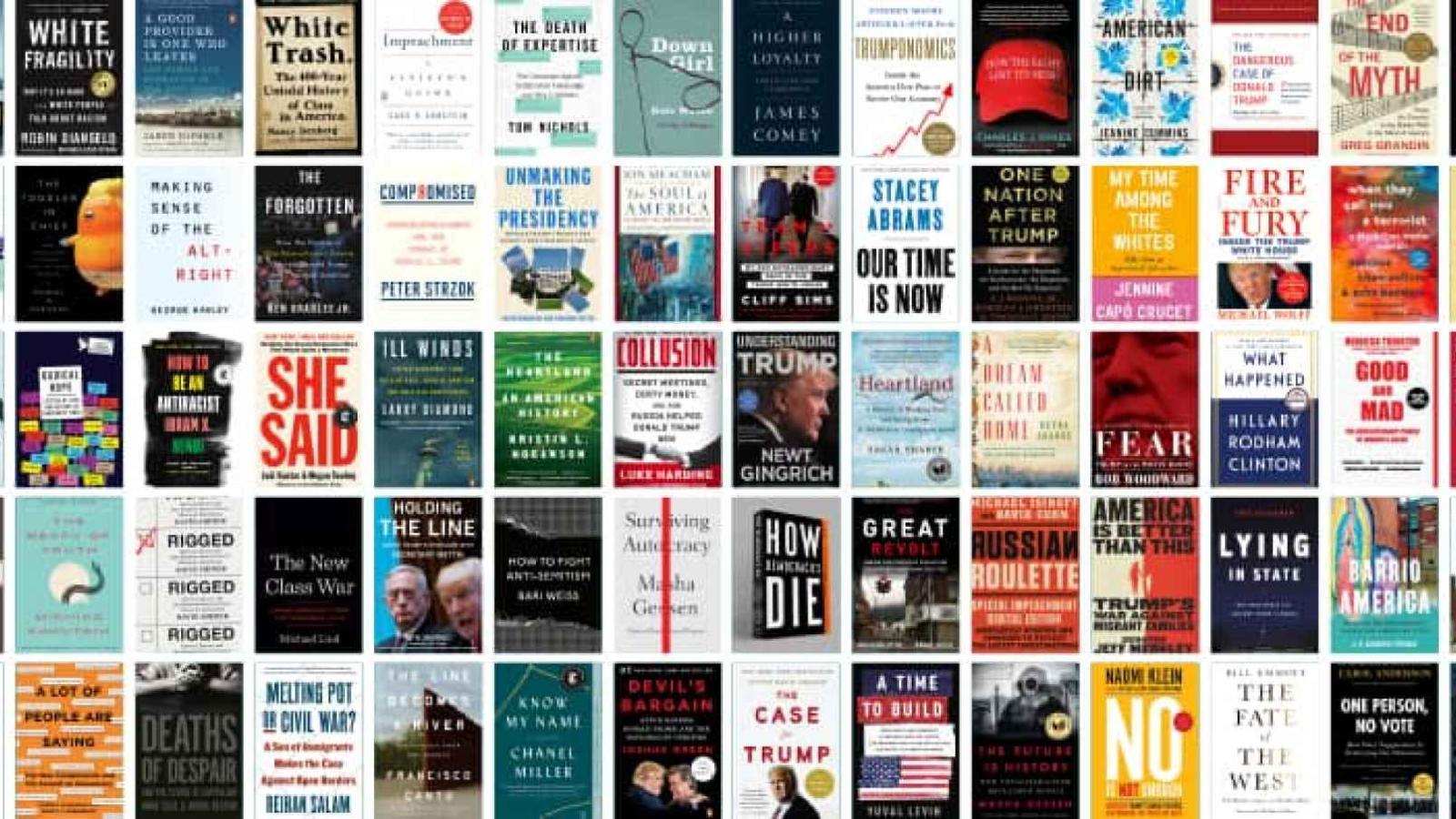

The presidency of Donald Trump was not just a boon for CNN, MSNBC, the New York Times, and the Washington Post. It was also a gift to the book business. There was, publishers found, an apparently insatiable hunger for anti-Trump screeds.

One after another of these tomes hit the bestseller lists. While there were the inevitable differences among them in style and perspective, virtually all shared a single theme: Trump was not just a president whose politics the authors disliked; he was the worst person ever to hold the office, unique in his bigotry, corruption, ignorance, stupidity, egomania – indeed, in the estimation of many, comparable to Hitler. In general, the author paid very little if any attention to Trump’s actual political ideas, programs, or accomplishments; instead, their focus was on his personality and personal views, real or imagined – and, by extension, on the supposed attitudes of Trump’s supporters, whose very enthusiasm for him was treated as a character flaw and, indeed, an existential threat to American democracy, tolerance, and social cohesion. Some, if not all, of the writers did not trouble to hide the fact that their disdain for Trump and his voters was rooted in snobbery, regional prejudice, and ideological rancor.

These books fell into a number of general categories. Some were works of reportage by journalists who covered Trump. Some, such as former FBI agent Peter Strzok’s Compromised: Counterintelligence and the Threat of Donald J. Trump (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020, 384 pages), former FBI director James Comey’s A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership (Flatiron, 2018, 312 pages), Comey’s Saving Justice: Truth, Transparency, and Trust (Flatiron, 2021, 240 pages), and former FBI deputy director Andrew G. McCabe’s The Threat: How the FBI Protects America in the Age of Terror and Trump (St. Martin’s, 2019, 288 pages) were by members of the intelligence community and former government officials. Some, such as Michael Cohen’s Disloyal: The True Story of the Former Personal Attorney to President Donald J. Trump (Skyhorse, 2020, 432 pages) and Mary Trump’s Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Creates the World’s Most Dangerous Man (Simon & Schuster, 2020, 240 pages), were by former associates and family members. Some were by psychologists who professed to diagnose Trump’s mental conditions; some were by NeverTrump conservatives; some pushed the Russian collusion narrative; some spun conspiracy theories. And some, such as How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them (Random House, 2018, 240 pages) by Yale philosophy professor Jason Stanley, Twilight of Democracy by Russian author Masha Gessen (Riverhead, 2020, 288 pages), and Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Autocracy (Doubleday, 2020, 224 pages), by longtime Washington Post columnist Anne Applebaum, linked Trump to historical fascism. We cannot examine each of these categories in detail but let’s take a quick spin through some of the more important ones, highlighting their distinctive qualities, after which we will consider what they have in common and above all what they reveal—not about Donald Trump himself, but about their authors. For Trump is a unique figure in American life who stands as a kind of Rorschach on which people project their deepest fears and prejudices.

First, a look at the works of reportage (to use the term loosely). It’s important to note at the outset that political reporting, as traditionally understood, went out the window when Trump came down that escalator at Trump Tower and, in the view of mainstream journalists, began a years-long national emergency Some even declared openly that this crisis required them to dispense with even an attempt at objectivity. They were now champions of the people against Trump’s tyranny and lies, whose job was not to report the news but to stand as the last bulwark of democracy. This self-dramatizing posture led to a great deal of narcissistic preening. And on this front, no one was more objectionable, and more ridiculous, than Brian Stelter and Jim Acosta-

Stelter, the George Constanza lookalike who hosts the risibly named Reliable Sources on CNN, weighed in with Hoax: Donald Trump, Fox News, and the Dangerous Distortion of Truth (Atria/One Signal Productions, 2020, 368 pages). “Like so many Americans,” he maintained at the outset, “I’m shocked and angry. So what you’ll get in these pages is not the Stelter in a navy blue blazer that you see on CNN. I’m writing this book as a citizen; as an advocate for factual journalism; and as a new dad who thinks about what kind of world my children are going to inherit. This story is about a rot at the core of our politics. It’s about an ongoing attack on the very idea of a free and fair press.” Many of these reporters sounded this theme, preening as courageous free-speech champions in the most vulgar and theatrical way imaginable, even though Trump posed no threat whatsoever to their free speech. In any event, this professed raison d’etre notwithstanding, the book was mostly a grab-bag of nasty Fox News gossip. On Election Night 2016, wrote Stelter, “Pete Hegseth and Jesse Watters walked around like they owned the building. They were drunk with power.” Without the help of one Fox exec, host Brian Kilmeade would be “a soccer coach in Massapequa” and commentator Brian Doocy would be working for Avis. Reading this book was like sitting at an airport bar next to for a Goodyear sales guy who wants to tell you all about the jerks at Michelin.

Another CNN star, White House correspondent Jim Acosta, whose behavior in the Trump press room earned him a national reputation as a buffoon and (evidently) the contempt of many of his colleagues, also cast himself as a free-speech hero in The Enemy of the People: A Dangerous Time to Tell the Truth in America (Harper, 2019, 368 pages). TV viewers familiar with Acosta’s ego (one sentence began: “Not to sound like Forrest Gump, repeatedly appearing at famous events…”) won’t be surprised to know that his book was as much about him as about Trump. Informed observers know that in response to media lies about him, Trump called them “the enemy of the people.” But for Acosta, Trump was the real enemy, unleashing “a profound assault on the truth” and obliging the media “to fight for the truth” and, in fact, “to tell the truth, even when it hurts.” And the biggest media hero of all was – who else? – Jim Acosta: “call me a showboater or a grandstander….I will go to my grave convinced deep down in my bones that journalists are performing a public service…even if we sometimes sound a little over the top. That noise is the sound that a healthy, functioning democracy makes.”

Acosta discussed the temporary suspension of his White House pass at length as if it were an international crisis. While having nothing to say about Hillary Clinton’s dismissal of Trump voters as “deplorables,” he throttled White House official Stephen Miller for saying that he, Acosta, had a “cosmopolitan bias.” (Miller’s concern about illegal immigration made him a bête noir for several of these writers, with Toobin mocking him as Trump’s “enabler” and Rick Wilson accusing him of seeking to “purge America of the brown people.) Miller meant that Acosta reflected big-city, blue-state politics; but Acosta couldn’t help reminding us that “the term cosmopolitan was used by Joseph Stalin to purge anti-Soviet critics” and by Nazis to describe Jews. This kind of connect-the-dots political analysis was common to books about Trump, in which factoids and random quotes were strung together to make the case that he was the reincarnation of Hitler. Asserting that he “would debate Miller anytime anywhere on…immigration,” Acosta seemed unaware that it wasn’t his job to debate but to report; indeed, his repeated snipes at popular Trump policies only underscored the fact that this supposedly objective reporter was always a partisan. Indeed, as we will see, all of these so-called reporters crossed that line when it came to Trump.

In Front Row at the Trump Show (Dutton, 2020, 368 pages), Acosta’s press-room comrade Jonathan Karl of ABC also highlighted Trump’s phrase “enemy of the people,” noting that it “was used to murderous effect by Maximilien Robespierre,” as well as by the Nazis and Stalin. Like Acosta, he complained that Trump’s criticism of the media might incite violence against journalists; but concern about anti-Trump violence never caused him, or any of these journalists, to temper their rhetoric. Nor did they acknowledge that during the Trump years the violence was almost entirely on the left. That said, Karl was rather fairer than the CNN men, admitting that Trump “had good reason to be outraged” by “the relentlessly negative tone of the news coverage” of his administration and by Obama holdovers’ leaks, which represented “a profound and unprecedented violation of the president’s trust.”

Bob Woodward was also relatively fair – until he wasn’t. In Fear: Trump in the White House (Simon & Schuster, 2018, 448 pages) – the title alludes to a Trump statement that “Real power is fear. It’s all about strength. Never show weakness” – and Rage (Simon & Schuster, 2020, 452 pages) – “I bring rage out….I always have” – the iconic Washington Post veteran actually cited insiders’ praise for Trump (a staffer who listened in on Trump’s calls to the parents of dead servicemen “was struck with how much time and emotional energy Trump devoted to them”) and quoted at length Jared Kushner’s insights into Trump’s leadership style. Still, he made his leanings clear: he denied that Antifa is an organization; he asserted a belief in systematic racism (at what point in his half-century-long journalistic career did Woodward become convinced of this?); and, in conversation with Trump, Woodward challenged his characterization of some Democrats as Marxists and – incredibly – asserted “there are no Marxists left.” In a brief epilogue to Rage, Woodward dropped his impartial-reporter pose and slammed Trump as disorganized, undisciplined, untrusting, and headstrong; in short, “the wrong man for the job.”

In A Very Stable Genius: Donald J. Trump’s Testing of America (Bloomsbury, 2020, 465 pages), Woodward’s Post colleagues Philip Rucker and Carol Leonnig painted what their publisher called “an unparalleled group portrait of an administration driven by self-preservation and paranoia.” For insight into the authors’ point of view, consider the index. The first few subentries under “Trump’s characteristics” were “ABUSE OF SUBORDINATES,” “ADDICTION TO MEDIA,” “ALIGNMENT WITH AUTHORITARIAN LEADERS,” “AVOIDING PAYMENT,” “BELIEF THAT HE IS ABOVE THE LAW,” and “CHILDISHNESS.”

In Donald Trump v. The United States: Inside the Struggle to Stop a President (Random House, 2020, 242 pages) New York Times writer Michael S. Schmidt celebrated White House counsel Donald F. McGahn II and FBI director James Comey for foiling Trump initiatives and trying to bring him down. Disloyal? Unethical? Treasonous? Not for Schmidt, who saw such people as heroes, especially if they leaked to him. Schmidt’s book is structured as a countdown to the release of the Mueller report, which he treats not as an exoneration of Trump but as a cornucopia of evidence of obstruction. He seems not to notice the irony of his fixation on this putative “obstruction” (in reality, a perfectly normal defensive response on the part of a president who is under concerted attack) even as he celebrates the very real, and criminal, obstruction by McGahn.

Veteran Manhattan media columnist Michael Wolff is a case unto himself. A serial fabulist who scorns journalistic conventions like factual accuracy or attribution of quotes, he’s considered dishonest even by dishonest journalists. For decades, he’s been accused of quoting off-the-record comments and inventing entire scenes out of whole cloth for his columns in New York magazine and elsewhere. In his bestselling Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House (Holt, 2018, 321 pages) and Siege: Trump under Fire (Holt, 2020, 352 pages), Wolff treated Trump mainly as a media phenomenon: major political issues got less space than Trump’s relationships with cable stars like Tucker Carlson, Sean Hannity, and Joe Scarborough. Like Woodward, Wolff interviewed numerous White House insiders; unlike Woodward, he focused not on policy but on personality, explaining that “Trump is probably a much better subject for writers interested in human capacities and failings than for most of the reporters … who are primarily interested in the pursuit of success and power.” Rather remarkably, one of Wolff’s main sources in both books was Steve Bannon (first off and then on the record), whom Wolff described as “the most clear-eyed interpreter of the Trump phenomenon I know, as the Virgil anyone might be lucky to have as a guide for a descent into Trumpworld – and as Dr. Frankenstein with his own deep ambivalence about the monster he created.” The book was excellent PR for Bannon, who was portrayed as the genius behind the throne, but its cinematically vivid, and alarming, portrait of Trump – who came off as a cartoon clown – and of his White House was not remotely convincing; indeed, many Trump administration figures lined up after these books’ publication to deny and denounce Wolff’s account. Indeed, although Wolff is the extreme case, all of these journalists’ books were of a piece. Plainly designed to affirm Trump-haters’ prejudices and confirm their worst suspicions, they had little to offer a Trump supporter other than portraits of the anti-Trump media mind at work – not just willing to bend the truth, but prepared to invent anecdotes and hurl mud in order to discredit a president in the eyes of American citizens.

On to the books that accused Trump of collusion with Russia. In True Crimes and Misdemeanors (Doubleday, 2020, 496 pages), CNN legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin dragged the reader through hundreds of pages of mind-numbing detail about the collusion charges, which, the results of the Mueller report notwithstanding, he persisted in treating as legitimate. If Attorney General Robert Barr concluded that Trump was innocent of conclusion, it was because he was a “toady” who ordered Rod Rosenstein to “whitewash” Muller’s work and whose decision to investigate the origins of the Russia lies amount to a “shameful” pursuit of “right-wing conspiracy theories.” (Not long after his book came out, Toobin was fired by the New Yorker for a headline-making onanism incident during a Zoom video call.)

The absurd Russia collusion charge, of course, was an industry unto itself, spawning other bestsellers such as Russian Roulette; The Inside Story of Putin’s War on America and the Election of Donald Trump (Twelve, 2018, 372 pages) by longtime D.C. scribes Michael Isikoff and David Corn. In a review of this book, even New York Times reporter Steven Lee Myers acknowledged that it didn’t offer proof of collusion; rather, just as Brian Stelter’s free-press manifesto turned out to be a collection of Fox News gossip, Russian Roulette wasn’t a deep probe into Trump-Putin ties but an “election diary.”

Back in 2004, writer and editor Craig Unger made a name for himself with the controversial House of Bush, House of Saud, in which he made sensational claims about business ties between the Bush family and the Saudi royals. (The publisher, Random House, canceled its UK edition to avoid a Saudi libel lawsuit.) In House of Putin, House of Trump: Donald Trump and the Russian Mafia (2018, 384 pages), Unger leveled many of the charges that would ultimately be dismissed by Robert Mueller in 2019. Did Trump explore building projects in Russia and sell Manhattan apartments to Eastern European buyers? Unger concluded he was Putin’s “asset.” Did the firm Trump SoHo have ties to a company called Bayrock, which in turn had “alleged ties to Russian intelligence and the Russian Mafia?” Trump “may well have been performing gigantic favors for Vladimir Putin without even knowing it.” Did Trump, after announcing his presidential candidacy, tell Hannity he could “get along” with Putin? Hence “[i]t was official. The Trump-Putin connection had gone public.” How this pathetic excuse for an argument got past a professional editor is anyone’s guess.

Then there’s poet-professor Seth Abramson, who, after gaining Twitter fame with a Trump conspiracy theory that was as preposterously complex as it was devoid of solid evidence, expanded his accusations into the so-called “Proof trilogy” – Proof of Collusion (Simon & Schuster, 2018, 448 pages), Proof of Conspiracy (Simon & Schuter, 2019, 582 pages), and Proof of Corruption (St. Martin’s, 2020, 578 pages). In these three doorstops, Abramson depicted Trump as plotting not only with Putin but also with the leaders of China, Venezuela, and several Middle Eastern nations. Suffice it to say that even many of Abramson’s fellow Trump-haters considered him a crackpot. It is certainly impossible to read his books without concluding that he is a kook of the first order.

Speaking of psychological diagnosis, let’s move on to the armchair psychologists. Trump inspired an unprecedented wave of armchair activism from American mental health professionals. Just as the journalists decided that Trump’s sheer awfulness compelled them to abandon their professional objectivity, these professionals agreed that Trump’s unique threat to the world permitted, nay required, them to violate the professional rule prohibiting psychological diagnosis at a distance. In 2019, 350 of these professionals signed a petition advanced by Yale psychiatrist Bandy X. Lee, George Washington University doctor John Zinner, and former CIA profiler Dr Jerrold Post and stating that the state of Trump’s mental health could prove “catastrophic.”

In Authoritarian Nightmare: Trump and His Followers (Melville House, 2020, 368 pages), Watergate veteran John W. Dean and Canadian psychologist Robert A. Altemeyer recounted Trump’s life story, which, they unconvincingly insisted, supported their obviously foregone conclusion that he’s an authoritarian personality type. Moreover, they suggested that Americans who continued to support Trump even “when he fired the director of the FBI, when he took children from their parents along the Mexican border, when he said he was in love with North Korea’s dictator, [and] when he sided with Vladimir Putin against U.S. Intelligence assessments that Russia had interfered in the 2016 election” must also be authoritarian. “Trump,” they predicted. “will be revered by multitudes of his supporters for the rest of their lives. As Hitler, Stalin, Chairman Mao, Saddam Hussain, and others were by those who strongly identified with these men’s policies. Nothing will ever convince most of Trump’s True Believers that he was not as wonderful as he said he was.” To their credit, Dean and Altemeyer did admit that they “have no formal training in psychiatric diagnosis, so our two cents worth of opinion about Trump’s mental health might not even be worth the two cents.” At least they were honest about that.

In Trump on the Couch: Inside the Mind of the President (Avery, 2018, 304 pages), Justin A. Frank, M.D., a Kleinian psychiatrist and author of Bush on the Couch (motivated by a “concern about Bush’s mental health”) and Obama on the Couch (which found that Obama’s chief psychological flaw was excessive bipartisanship), Frank maintained that Trump’s “lying,” “narcissism,” “sexism,” “destructiveness,” and “racism” rendered him unfit for office.

Even more irresponsible was The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump (Thomas Dunne, 2019, 544 pages), edited by Bandy X. Lee, in which no fewer than thirty-five psychiatrists, mental-health experts, and others presumed to assess Trump’s mind. Their diagnoses varied widely: Lance Dodes called Trump a sociopath; Gail Sheehy thought he suffered from a “trust deficit”; John D. Gartner said he was “evil and crazy”; for Philip Zimbardo and Rosemary Sword, the problem was “narcissism in extremism”; Craig Malkin went with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD); James A. Herb concluded that he had both NPD and histrionic personality disorder. Lee’s book directly challenged the Goldwater rule, which, instituted by the American Psychiatric Association after mental-health professionals commented on 1964 presidential candidate Barry Goldwater’s sanity, prohibits its members from diagnosing public figures. Leonard L. Glass argued that the Goldwater rule “blocks psychiatrists from helping to explain widely available and readily observed behaviors,” even when, as in Trump’s case, “there is an impressive quantity of …emotional responses and spoken ideation for us to draw on.” In short, this book’s authors unprofessionally used their professional credentials to defend judgments that were grounded in political and personal animus, not in serious psychiatric evaluation. Lee followed it up with Profile of a Nation: Trump’s Mind, America’s Soul (World Mental Health Coalition, 2020, 186 pages) in which, taking a step beyond the psychoanalysis of Trump, she diagnoses his voters as suffering from a “shared psychosis” rooted in “narcissistic symbiosis”—an ominous step in the direction of declaring half of the population of America insane and in need of treatment. (In late March 2021, the Yale Daily News reported that Lee had been fired by Yale the previous May for these violations of psychiatric ethics.)

An extension of this category are books alleging that Trump is a sinister cult leader whose followers are mindless idiots. In The Cult of Trump: A Leading Cult Expert Explains How the President Uses Mind Control (Free Press, 2019, 296 pages), professional cult deprogrammer Steven Hassan compared Trump to Sun Myung Moon, L. Ron Hubbard, Jim Jones. David Koresh, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, and Keith Raniere – not to mention Hitler, Stalin, and Putin – and explained how Trump used their methods to win acolytes. For example, “Trump has claimed to know more than anyone else about many things – renewables, social media, debt, banking, Wall Street bankers, money, the U.S. government,” and so on. The very premise that Trump functions as a cult leader was absurd and showed that it is the author himself, not Trump’s followers, who is mentally unhinged. Trump supporters aren’t victims of mind control, and they don’t view Trump as anywhere near perfect, let alone quasi-divine. They can laugh at his foibles — which a cult member never does (hence the phrase “drinking the Kool-Aid”). But they support him because, unlike other politicians, he takes them and their concerns seriously.

This is more than you can say about Hassan, who regards Trump voters as sheep. One might think his obviously meretricious argument would fail to gain traction in respectable circles. But especially since the November election, the idea that Trump voters are cultists has been echoed widely, with CNN and MSNBC talking heads insisting that they need to be “deprogrammed.” Why? Because they deny the “truth” that Trump lost and cling to the “lie” that the election was stolen. It’s also been suggested that there’s need for “de-Baathification” of the GOP, which means Trump is tantamount to Saddam Hussein.

Then there are the Never Trump Republicans – a special category of conservative policy wonks and political operatives left high and dry by Trump’s populist wave. Even though a lot of what he did in office was consistent with conventional GOP policy, these malcontents could not get over the loss of their power and influence, and assuaged their pain by chasing after cable-news contracts and book deals.

Rick Wilson is a Republican strategist, and one of the founders of the Lincoln Project, a group of prominent Never Trumpers. In Everything Trump Touches Dies: A Republican Strategist Gets Real about the Worst President Ever (Free Press, 2018, 336 pages), his business was, quite simply, name-calling on an epic scale. Trump, he pronounced, is “terrible, sloppy, shambolic,” “degenerate, unrepentant,” “uneducated and uneducable,” “malleable, crass, and dishonest,” a “jackass,” “a self-obsessed Narcissus in a fright wig,” “a man with a notoriously shallow intellect, and a marked inability to stick to a consistent line of thinking,” a “serial adulterer with a desperate need to have his manhood validated,” a “faux billionaire up to his ample ass in debt to God knows who,” “a president without a shred of dignity,” and “the avatar of our worst instincts and darkest desires as a nation.” He has a “blustering ego,” a “con-artist modus operandi,” a “third-world generalissimo swagger,” “a gnat-like attention span,” “the worst economic ideas of the 19th century,” “tiny, tiny lemur-paw hands,” “a grasp of history derived solely from movies and television,” an “exotic dead-animal hairstyle,” “poor impulse control and a profoundly superficial understanding of the world,” not to mention “spectacular vulgarity, vanity, and [a] gimcrack gold-leaf aesthetic.” A producer of “rhetorical turd[s]” whose presidency is one long “exercise in self-fellation,” Trump, a.k.a. “King Donald the Mad,” Wilson postulated – momentarily joining Trump’s self-appointed psychoanalytic team – “might just be insane…legitimately, clinically insane,” which is to say “shithouse-rat crazy.”

What to say? Attacking Trump as vulgar and unhinged, Wilson himself came off as…well…vulgar and unhinged. Granted, he cheerfully admitted to being a “gleeful hatchet man for the GOP” and an “equal opportunity asshole”:

As a Republican consultant for over 30 years now, I don’t expect you to love me. Honestly, I expect you to think of me as being morally ambiguous, politically opportunistic, vicious, spiteful, and committed to my bottom line before anything good or wholesome. Spoiler: mostly true. This has never been a business – particularly my former niche of campaign advertising – informed merely by a deep sense of wonder at the miracle of our Republic. Just win, baby.

Presumably Wilson felt that this kind of self-abasement was necessary to ingratiate himself with his liberal audience. To be sure, Wilson briefly dropped his proudly amoral “just win, baby” persona to pretend that he admired men with values: the GOP, he averred, was “once defined by the smart articulation of a conservative worldview that sought to limit the power of the state [and] ensure the primacy of our values.” And it exuded decency:

I had the honor to work as an appointee in the administration of George Herbert Walker Bush. Our 41st president led by example, expecting all of his appointees, from Cabinet secretaries down to the lowest-level staffer, to reflect the values of patriotism, modesty, judgment, humanity, and service that had shaped his career. Moral examples work.

Wilson’s book sold well, and he followed it up with Running against the Devil: A Plot to Save America from Trump – and Democrats from Themselves (Crown Forum, 2020, 326 pages), a guidebook for Democrats on how to defeat Trump’s re-election bid. It, too, was nasty, calling Bill Barr a “lawless, bloodless enforcer,” joking that Jeanine Pirro is “President of the Franzia Boxed Wine Case of the Day Club,” dismissing Obamagate as “ludicrous,” and featuring numerous cruel attempts at humor at the expense of Melania Trump. As for Trump himself, he “makes Nixon look like a rookie” and “makes the noncontroversies of Obama, the Bushes, Clinton, and Reagan feel utterly trivial by comparison.” As for Trump’s rallies, they’re “a couple pointy white hats short of a Klan rally.”

Stuart Stevens, author of It Was All a Lie: How the Republican Party Became Donald Trump (Knopf, 2020, 256 pages), is also a longtime GOP operative. Yet while Wilson’s book depicted the GOP’s modern history as noble, Stevens saw it as ugly. Like Wilson, he felt it necessary to issue a mea culpa for having ever been a Republican in the first place. He thus aligned himself with liberal prejudices by cravenly throwing himself and his party under the bus. Thus Stevens confessed to having “played the race card in my very first race,” making him part of “the long-standing hypocrisy of the Republican Party.”

As with Wilson, his only defense was sheer cynicism: “I honestly didn’t think about it much….Looking back, I often think I represented the worst of the American political system, just focused on winning without regard for the consequences.” He then cast Trump, a former Democrat who’d played no part in the GOP’s purported historical racism, as “the logical conclusion of what the Republican Party became over the last fifty or so years, a natural product of the seeds of race, self-deception, and anger….[T]here is a direct line from the more genteel prejudice of Ronald Reagan to the white nationalism of Donald Trump,” whom he called “the most openly racist president since Andrew Johnson or his hero Andrew Jackson.”

How exactly is Trump racist? You would think that such an incendiary charge against a sitting president would require some kind of evidence. Stevens explains that after NFL players took a knee during the national anthem, Trump had the gall to criticize them for politicizing a sporting event. What’s more, he did it in Alabama, “where more than three hundred African Americans were lynched.” Apparently this is some kind of dog whistle to his racist supporters and a retroactive endorsement of lynchings that occurred in the last century.

David Frum, the George W. Bush speechwriter who coined the phrase “axis of evil” and promoted the invasion of Iraq, is now a leading Never Trumper who’s called Trump “[t]he worst human being ever to enter the presidency.” In two books — Trumpocracy: The Corruption of the American Republic (Harper, 2018, 320 pages) and Trumpocalypse: Restoring American Democracy (Harper, 2020, 272 pages) — he depicted Muslims as innocent victims and Antifa as largely a Fox News fantasy. He introduced the black Trump supporter Candace Owens by quoting a statement by her that Rep. Ted Lieu used at a 2019 House hearing to make her look as if she was “legitimiz[ing]” Adolf Hitler. Citing Trump’s words of condolence after the June 2016 jihadist massacre at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Frum stated (despicably) that “Trump cared for the safety of gay Americans only in order to accuse Muslims.” After a long career on the right, moreover, Frum flipped to Democratic positions on a range of issues from D.C. statehood to socialized health care, and proclaimed that leftists were now the “forces of freedom” while Trump represented “the most dangerous challenge” to freedom. The more Frum flailed, the more obvious it was that Trump’s real crime, for him, was trying to drain the swamp in which Frum so comfortably swims.

Finally, from Susan Hennessey and Benjamin Wittes – both senior fellows at the Brookings Institution – there is Unmaking the Presidency: Donald Trump’s War on the World’s Most Powerful Office (Farrar. Straus and Giroux, 2020, 432 pages). Their thesis: America has “never before had as president a man more obviously misplaced in the office” than Trump, and “[t]his mismatch [was] fundamentally a question of character.” The authors begin by noting that a pastor at Trump’s inaugural read the Beatitudes, and that as he ticked off “the list of favored attributes – those who are merciful, clean of heart, peacemakers – each stood in sharper contrast to Trump than the one before.”

“From the