Mark Satin’s Long Journey from Radicalism to Reality

By Bruce Bawer

I’m surprised I’ve never heard of Mark Satin, author of the fascinating new book Up from Socialism, which  is a memoir of his long and varied life as a leading member of a strain of political activism that I confess to knowing a good deal less about than I probably should. Born in 1946, Satin was raised in Moorhead, Minnesota, and Wichita Falls, Texas, and joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) while studying at the University of Illinois. The SNCC took him down South, specifically to Holly Springs, Mississippi, where he was part of a group whose ostensible goal was to register black people to vote. It was there that he found himself clashing with most of his co-workers.

is a memoir of his long and varied life as a leading member of a strain of political activism that I confess to knowing a good deal less about than I probably should. Born in 1946, Satin was raised in Moorhead, Minnesota, and Wichita Falls, Texas, and joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) while studying at the University of Illinois. The SNCC took him down South, specifically to Holly Springs, Mississippi, where he was part of a group whose ostensible goal was to register black people to vote. It was there that he found himself clashing with most of his co-workers.

Why? Because although he sought to help formulate a new, more humane society, Satin was – surprisingly – not a socialist. He was appalled by his co-workers’ disdain for the NAACP, which they considered too mainstream. He’d run into similar trouble with the radicals back in Illinois, who rejected one of Satin’s favorite novels, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, “because it appeared to present Black people as being partly at fault for their plight and was ‘viciously anti-Communist’ to boot.” (He even liked Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead.) In the same way, Satin was put off by his fellow activists’ worshipful attitude toward hardcore Communists like Frantz Fanon and Herbert Marcuse.

He didn’t stay there long. Between the anti-white racism, the ineffectiveness of the operation, and the ever-intensifying Marxism, Satin decided it was time to move on. His next stop was SUNY-Binghamton, where he joined the radical group Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). It, too, was a nest of Marxists, but he “clenched my teeth” and did his part. He helped the group to grow and ended up in charge of it, replacing the standard Marxist texts with some of his own eclectic selection of favorite books by the likes of James Baldwin, Rachel Carson, Peter Drucker, Erich Fromm, Paul Goodman, Jane Jacobs, Vance Packard, and, yes, even Ayn Rand. There was widespread resistance to this move.

His next big change was brought about by the prospect of being drafted to fight in Vietnam – a war to which he was morally opposed. Instead of waiting to be shipped off to Nam, he fled to Canada, specifically to Toronto, where he went to work at an office, a division of Canada’s Students United for Peace Action (SUPA), that was devoted to helping other draft dodgers. He found the work rewarding. He fell “in love with” the men who came to him for help. But here, too, he ran into ideological conflict. SUPA was “deeply hostile to capitalism.” Some of his new Maoist colleagues were far more interested in lying around discussing ideology than in helping the people they were supposedly there to help. When Satin mimeographed a how-to guide for draft dodgers, he was savaged for not including “political analysis” or having a “political line.” He was almost fired for giving an interview to the mainstream press. He was called a “little imperialist.” And when he wrote and published an even more comprehensive manual for draft dodgers emigrating to Canada, he endured another round of “ambivalence, bordering on hostility.” Meanwhile he fell in love with a woman who was devoted to “the Revolution,” who adored Mao and Castro, who denounced him as a “FASCIST CREEP,” and who pronounced that he and another wayward soul in the group needed “to go to re-education camps.”

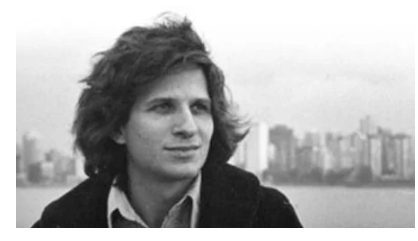

Next stop: Vancouver, where Satin enrolled in the University of British Columbia, then won a scholarship to the University of Toronto, where he designed his own Ph.D. program in “new-paradigm politics,” with a reading list that included Lewis Mumford and Doris Lessing. But at UT the problem he faced was the opposite of what he’d gone through at the SNCC, SDS, and SUPA: his status as a draft dodger turned off his more conservative fellow students and professors. After a few weeks he was back in Vancouver, working on a book that he conceived of as “the first comprehensive expression of the ideology that would dominate non-traditional radical politics for the next 50 years.” New Age Politics was “post-socialist,” rejected both the left and the right, and outlined a form of political thought that drew on “the spiritual, ecological, feminist, human-potential, nonviolent-action, decentralist, and global movements of our time” with the goal of “transforming the world,” no less. It proved to be a big success in certain activist circles. One big plus was that soon after its release, the new U.S. president, Jimmy Carter, pardoned all draft dodgers unconditionally, enabling Satin to tour America promoting his book. “For our whole lives,” he told one audience, “our political visions have come from Marxism or liberalism! But roll over, Karl Marx! Roll over, James Madison! Our own original vision is finally emerging….”

I’ve read more than my share of histories of the New Left. But I’m less informed about the history of the New Age – or “transformationalist” – movement, which was something else again. Rejecting the USSR and Mao’s China as role models, it was all about “new paradigmers” and “consciousness” and the “New Age spirit” and the purported desire to “build a kinder, juster world.” Even when I was a kid it all sounded totally fatuous to me. In the pages recounting his promotion of New Age Politics, we read about Satin’s appearances at gatherings of “nutritionists,” “decentralists,” and “lesbian ecofeminists.” Among the activists with whom he began to socialize with were an astrologer and a student of mime and puppetry. He also met the futurist Alvin Toffler, whose massive bestseller The Third Wave was, according to Satin, “a sort of high-tech-savvy version of New Age Politics.” Eventually Satin gathered around him a sizable group of “transformationalists.” “Many people,” he writes, “assume that the ideas associated with transformational politics and the Green New Deal achieved their first organized American expression in the U.S. Green Party. In fact, they achieved their first organized American expression in the New World Alliance, the group that came out of my 1978–1979 networking tour.”

That group was founded in New York in 1979. Its goal: filling the world with “a spirit of love and inclusion” and “consensus” and “empathy.” Reading Satin’s account of its principles, I’m reminded of the old Coke commercial: “I’d like to teach the world to sing in perfect harmony….I’d like to buy the world a Coke and keep it company.” Its “Ten Principal Values” were “hope, healing, rediscovery, human growth, ecology, participation, appropriate scale, globalism, technological creativity, spirituality.” One member belonged to an organization called Planetary Citizens; another was with the World Future Society. You’d have thought that Satin’s experiences with the petty, disturbed, divisive, argumentative, and competitive fellow members of previous do-gooder groups would have made him realize he was something of a naif who was dealing with morons and lunatics and tilting at windmills. Not yet.

Sure enough, at one early session of the New World Alliance, one member accused another of (literally) “working on behalf of the Devil.” There were infantile arguments in which members complained about their feelings having been hurt, in response to which other members pleaded with them “to let go of ego, see each other as an infinite potential of wisdom.” One member of the fundraising committee refused to allow it to proceed with its work unless more minorities were recruited. And Satin got so angry over the group’s failure to pay him his agreed-upon salary that he threatened to take them to court. It all sounds like something that would make any halfway sane person run for the hills. In any case, it certainly doesn’t sound like an organization remotely capable of changing human nature itself into something magnificent and glorious. Indeed, it soon became clear that the New World Alliance, was going nowhere fast, and once again Satin found himself walking away. Indeed, the New World Alliance “soon bit the dust and its virtual successor, the U.S. Green Party movement, was eventually taken over by its own far-left faction.”

Satin went on to publish the New Options Newsletter (1983-92). His “first major article” for it “was a critique of traditional peace groups for their self-righteousness, incessant America-bashing, and tiresome leftist ideology—and, more importantly, a celebration of some new peace groups for encouraging members to think outside the box and for promoting such positive approaches as win-win conflict resolution and citizen diplomacy.” Again there was friction: Satin and his chief assistant had fundamental political disagreements and soon got to the point at which “we could barely stand the sight of each other.” He ended up firing her. It’s unintentionally hilarious to read about all these institutions at which Satin worked where the objective was to introduce perfect harmony to the planet but where Satin couldn’t even get along with the person in the next office.

After his newsletter became a one-man operation, Satin was happy. He could sit alone in his apartment and wax poetic about human harmony – he refers to it as writing with a “feeling-tone” – without actually having to interact excessively with other human beings, an activity that almost invariably seemed to lead to unpleasant clashes. Over time New Options became “the go-to transformational political newsletter for the social change movement.” Meanwhile he’d also been helping to get the U.S. Green Party off the ground. At its founding meeting, Satin and other attendees came up with the movement’s key concepts, including “redistribution of power,” “no more nuclear weapons,” “connectedness to the earth,” and “female principle [as] relatedness, context, empathy.” But not only did the party start to pull “the transformational movement away from its new-paradigm roots and back to socialism”; for all its devotion to “empathy” and the like, it also occasioned yet more bitter arguments between Satin and other people who, while envisioning themselves as potential creators of a newer, gentler, and kindler world, routinely exploded at the drop of a hat. In fact Satin’s book is, in large part, a portrait gallery of unbelievably infantile, stupid, unstable, narcissistic, power-hungry, and just plain horrible misfits.

Finally – around the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall – Satin started to snap out of it all. As he puts it, “I could no longer wholeheartedly buy into the idealistic visions I was in the business of promoting.” He found himself reflecting: “How can I transform the world if I refuse to be part of the Real World?” After a movement friend of his, Gerald Goldfarb, was shot by a jealous lover, he pondered the fact that “[p]robably a majority of transformational activists, male and female, lived the way Gerry and I did in those days, collecting lovers with little regard for the emotional fallout. Thanks to books like my New Age Politics and rags like my New Options, we were ideologically confident we could hold such natural human emotions as jealousy, competitiveness, and possessiveness at bay, even ‘transform’ them over time with the right personal values and social structures. After Gerry’s murder, I began to lose faith in that gospel and the lifestyle it made possible for me.”

His job at New Options, he now perceived, was to “console…activists by telling them the world is really terrible, so it’s okay they underachieved—so long as their dreams are pure!” He was 42 years old when he came to this realization. It didn’t help when Satin, who had begun his career trying to help persuade blacks in Mississippi to register to vote, was punched violently on a Washington, D.C., street, for no reason whatsoever, by a brutal member of a black youth gang. So much for all his years of pretty rhetoric about social transformation. “I had felt the presence of evil in the world,” Satin writes. “I would never walk the streets with the same at-homeness that I’d felt before. Worse, I would never again buy into the visionary political belief that all people are basically good, and that all the problems of the world can be fixed by coming up with ‘new options’ until the correct ones are found.”

So what did he do? He went to NYU Law School and then got a job at a law firm. “I had spent my entire adult life in t-shirts or ill-fitting Goodwill shirts and blue jeans,” he recalls. But at NYU, he decided to start dressing like his fellow students. “The clothes those kids were wearing weren’t ostentatious. It just looked like they belonged to a different world—a positive and constructive one. And I wanted to belong to that world too..” Moreover, “I found that I didn’t just like myself better in tasteful, quality clothes. I liked the world better, and felt I had more say in it.” He also realized that his touchy-feely writing style was frankly inferior to that of his law-school classmates. He’d focused too much on feeling and not enough on thinking – on logic, on reason. Also, he’d spent his life bouncing from one superficial relationship to another; at law school, he saw students half his age forming relationships with an eye to marrying and having children. He realized that his friendships had always been based on shared politics. He found himself confronted with the fact that the world outside of the activist bubble wasn’t really so bad after all. He discovered that many of his fellow law students – and many lawyers – were “committed to making this world a better place.” And he learned the value of rational hierarchies, which had been anathema to him for two decades.

There was more. He took a course with Derrick Bell, founder of Critical Race Theory, who read to the class from a story he’d written, the premise of which was “that white Americans would happily round up and sell all Black Americans to traders from another planet if we could.” The white students in the class were stunned, and when Bell asked Satin over lunch what he made of the story, Satin replied honestly that “the racism I’d seen in Texas and Mississippi…was largely gone….Then I told him that what whites were feeling today was sheer exasperation based partly on the disproportionate amount of trouble some Blacks were causing in and around some public schools, and partly on the wildly disproportionate amount of violent crime some Blacks were committing.” Whites weren’t racist, in short, but many of them were exasperated by the behavior of many blacks, and that state of affairs wouldn’t change “until Black intellectuals like him publicly admitted the seriousness of those two problems or stopped blaming them all on poverty and racism.” Satin had changed his views 180 degrees. And Bell was outraged.

Satin experienced similar unpleasantness with a feminist professor who dissed men and who, on one occasion, invited Bernadette Dohrn, founder of the Weathermen terrorist group, to serve as guest lecturer. Since Dohrn’s monstrous activities “had contributed to the death” of a friend of Satin’s many years earlier, he skipped that class. But for the most part he appreciated his NYU Law education. He learned to think on a higher level. He came to respect David Horowitz’s memoir Radical Son, about being a red-diaper baby and ultimately leaving the New Left. Not that Satin left behind the idea of coming up with grand formulations for social transformation. In 2004 he published Radical Middle, which called for “a politics that dares to suggest real solutions to our biggest problems but doesn’t lose touch with the often harsh facts on the ground.”

I’m ten years younger than Mark Satin. We’re at opposite ends of the Baby Boom generation. His cohort gave us hippies and radicals. My cohort got a load of his cohort, people who were 18 when we were 8, and in reaction a great many of us rushed to embrace normality. The story of Satin’s career makes for captivating reading because it provides a window on a sizable subculture that existed in my own country throughout my adult life but that I was only vaguely aware of – but never had the remotest actual contact with. For decades Satin and I were both writers, both commentators on the world around us, but nothing he ever wrote made it onto my radar. In fact the entire language of his movement couldn’t have been more alien to me. From childhood on, to be sure, I heard snippets of it – and winced at every word. Even then, though I’m sure I was naïve about a lot of things, I wasn’t naïve about the capacity of the average human being to totally overcome human nature. It’s riveting to read about a man whose naivete on this question lasted into his forties but who finally, thank goodness, joined the real world. Up from Socialism tells an absorbing story, but we never quite figure out, alas, what on earth made this not unintelligent man spend so many years buying into sheer fantasy. Then again, his number is legion. At least he’s one of the few who eventually woke up.

First published in Front Page magazine