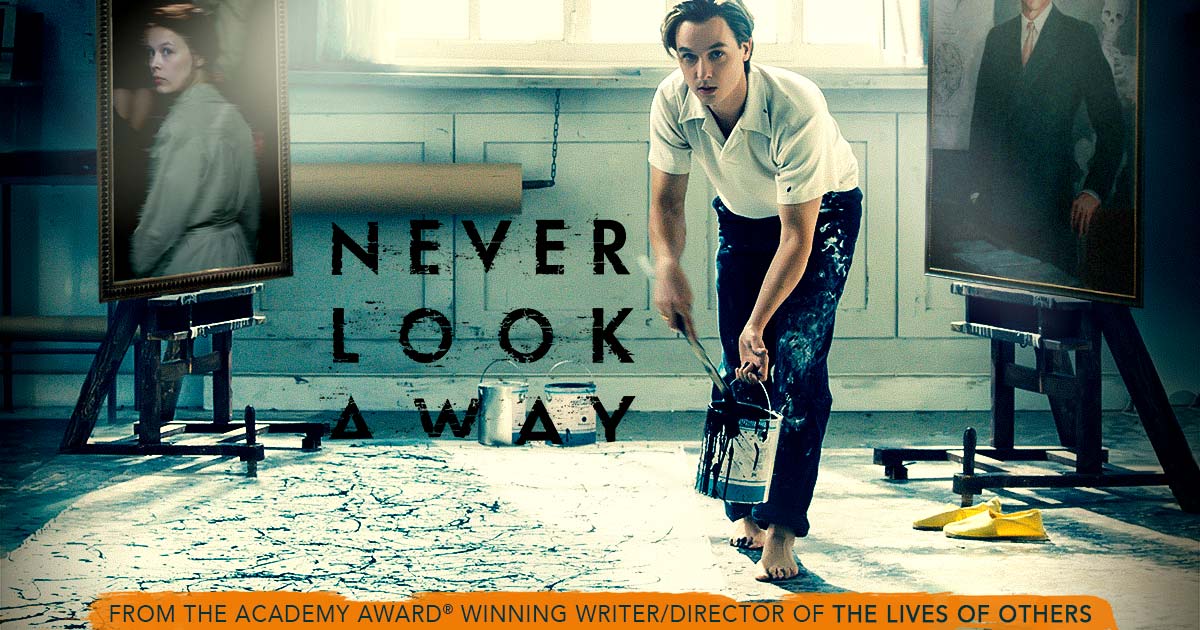

Never Look Away

A film that captures the nature of both Nazism and Communism—as well as the transcendent and brooding power of Art, Love, and Truth.

by Phyllis Chesler

And, for more than three hours, I never did. Time stood still. I was swept up into a moving panorama of pre-and post-WW2 Nazi Germany—every bit as amazing as the film The Russian Ark which captures 300 years of Russian history.

Please understand: I can no longer bear movies about Nazis who, today, are the cheap and safer stand-ins for other looming evil-doers and Jew-haters. I did not really like Schindler’s List—imagine that! And why? Because, while it focuses on a good German who saved a thousand Jewish lives, Spielberg does not simultaneously hold in his artistic embrace the six million who were not saved. I much prefer Defiance, The Counterfeiters, The Darien Dilemma, and Operation Finale. Resistance and Justice interest me deeply.

Also, understand: While my apartment is being renovated I am holed up at Hotel Horrible in the city’s poshest district and since I’m quite miserable, I’ve decided to partake of Manhattan’s fabled Culture: The ballet, the cinema, the opera, and of course, Broadway. And so I’ve been watching movies, both in my hotel quarters via Roku and in actual theaters as long as they are still standing.

And now to my latest film and its awesome and splendid themes.

From the title in English, (Never Look Away), one might think it a horror movie but the film is far from that; actually, it is a horror movie but one that does not disguise its preoccupation with evil in a secondary way. The film captures the nature of both Nazism and Communism—as well as the transcendent and brooding power of Art, Love, and Truth.

The movie embraces it all: The Nazi doctor who “euthanized” (gassed) the mentally ill—and then the Jews, the gypsies, the male homosexuals, the political dissidents, followed by the victorious Russian Communists who then occupied what became East Germany where they tried to crush all individuality, deaden every soul, for the greater glory of “the working class.”

The film is not propaganda. As in life, the evil are not all apprehended and brought to justice. A few are caught and tried, many escape, some land on their feet for the rest of their lives. While the film also depicts a romance and marriage between Kurt and Elllie Seeband, née Elisabeth, gorgeously played by Paula Beer, the sins of the fathers lie heavily upon them—and they COMPROMISE the next generation.

Despite the historical sweep, we come to care about the characters, they are real, haunting, pitiful, brave, human. As the protagonist, Kurt Barnert and his aunt Elisabeth (beautifully played by Paul Schilling and Saskia Rosendahl) both understand: “Everything that is true is beautiful.”

In his Ode on a Grecian Urn, Keats put it this way: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all Ye know on earth and all ye need to know.”

Kurt is an artist. He speaks little. He is watchful, keen-eyed, not very emotional. But he ultimately depicts everything in his art work, beginning with the loss of his beloved aunt to the Nazi atrocity—and the capture of the Nazi doctor who headed the “eugenics” and euthanasia program. He was only a child, but now he sees everything, he remembers it all, and he turns Historical Memory and Loss into Art.

His aunt, the very kind and creative Elisabeth is gassed, presumably as a “schizophrenic,” by the very sadistic Nazi doctor, “Herr Professor Carl Seeband,” brilliantly played by Sebastian Koch, who eventually becomes Kurt’s father-in-law. The Nazi past remains in play, as well as up close and very personal. The director, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck has not forgotten anything.

He is a great filmmaker. His cast is superb. The cinematography (Caleb Deschanel) and the music (Max Richter) is haunting, spiritual, uplifting, awesome.

Kurt’s character is based upon the life of the German artist Gerhard Richter—who apparently does not like the liberties taken with his biography.

But for me, time stood still. I lost all sense of it and sat there mesmerized for more than three hours.

I suggest that you all see this wonder, this painful and beautiful rendering of the 20th century in Germany.

First published in Israel National News.