Once Upon a Time in Moscow

by Theodore Dalrymple

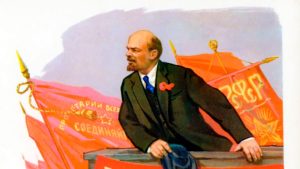

Once in Moscow, before the downfall of the Soviet Union, I stood in the line to file past the alleged corpse of Lenin in his mausoleum in Red Square. Behind me was a man from Brooklyn.

“This country is the hope of the world,” he said.

He was an old-fashioned communist of a type that had by then become rather rare but was once very common. The defects of communism, to say nothing of the mass crimes committed in its name, were so undeniable that only the blindest of the blind, such as the man from Brooklyn, could adhere to their former illusions.

In fact, the Iron Curtain had for some years served a useful function in the West. The horrors of life behind it were so well documented that they exerted a dampening effect on the fantasies of those who might otherwise have been inclined to utopian dreams. The example of a utopia that had swiftly turned into a murderous hell everywhere it was tried encouraged a degree of realism even among intellectuals.

With the implosion of the Soviet Union, however, the utopian imagination was set free to roam. It no longer had to check itself against any existing reality, and the recent past was soon forgotten even by the young in countries that had suffered it. Utopian schemes abounded: sexual identity without limits or boundaries, a world free of carbon dioxide production, countries without borders, equal representation of all racial and other demographic groups in positions of power, wealth or influence, and so forth.

Of course, the reverse side of utopianism is authoritarianism, even totalitarianism. Since the utopian aims at perfection, anyone who opposes him must be a bad person, evilly disposed. It’s therefore only right that such people should be silenced, if necessary by force. Never in my lifetime has the desire been greater to shut people up or prevent them from speaking in the first place. It goes deeper even than this, in fact: Children as young as five or six are now being indoctrinated so that they will grow up incapable of having “wrong” thoughts about such matters as sex and gender and global warming.

Just because something is impossible doesn’t stop people from trying to put it into practice, nor does the sheer unrealism or even stupidity of ideas mean that they can have no practical effect or influence. Indeed, their practical effect or influence can be profound and disastrous.

At the present conjuncture, for example, Europe finds itself as weak as a baby in the face of Russia, despite the fact that it has an economy many times the size of Russia’s and a standard of living incomparably higher.

One of the reasons for this seeming paradox—it’s usually polities with the strongest economies that have the upper hand—is the energy policies pursued by European countries. Under pressure from “idealistic,” that is to say utopian, green activists, they have decided to reduce their consumption of oil, ban coal, decommission nuclear power stations and prohibit the practice of fracking. Britain stopped oil and gas exploration in the North Sea, and Germany chose the very time of the Ukrainian crisis to close its last nuclear power stations.

At the same time, Europe is committed to the electrification of all its vehicles (which initially, at any rate, will act as a heavy tax on the poor). The extra electricity required will have to be generated somehow. So-called renewables are unreliable: The wind does not always blow and the sun does not always shine. For the moment, the only plausible solution is natural gas, much of which must be imported from Russia. One may accuse Putin of many things, but not of stupidity: He’s fully aware of the lever this has put into his hands, and many people believe that he has been funding ecological movements in Europe that stymie a more realistic policy. Whether or not this is true, he now has the perfect tool for causing serious stagflation in Europe, restricting the supply of a vital productive factor and raising the price of everything.

It isn’t even as if the green utopians care much for the environment, or at any rate not for its beauty. They would be happy to see the land covered with hideous, noisy, wildlife destroying wind farms. What they care for is not power generation, but political power, their own power to dictate policy irrespective of consequences.

Thus, the green utopians, whom cowardly or corrupt governments have appeased, have strengthened Putin’s hand and condemned Ukrainians to a very anxious future.

The same kind of people believe in a world without conflict in which armed forces are unnecessary at best and a menace at worst. A combination of utopian pacifism and utter military reliance on the United States has disarmed Europe completely: It probably couldn’t long withstand an attack from Turkey, let alone from Russia.

Meanwhile, American power is itself being undermined and weakened by utopian social movements that are making its armed forces a laughing-stock to the Russians and Chinese. Their mission is no longer to defend the country and its interests but to further the cause of so-called diversity, inclusion, and equity, in the same way that universities and colleges have been sapped of their true purpose. Diversity, inclusion, and equity are like termites in a wooden building: The building appears to be just the same as it always was until it suddenly collapses in a heap of sawdust. Suffice it to say that it’s doubtful that the armed forces of Russia and China are much concerned with diversity, inclusion, and equity—which in any case are, in true Newspeak fashion, the very opposite of what they appear to mean. They are really uniformity, exclusion, and injustice.

We shouldn’t exaggerate: We do not yet live in fear of the midnight knock on the door, and that is something to be grateful for. But all the academics to whom I speak, for example (who I admit may not be a representative sample), live in fear, for their jobs, for their grants, for their promotion, for their reputation, occasionally even for their safety. The totalitarians are winning all the way along the line.

First published in The Epoch Times.