by Hugh Fitzgerald

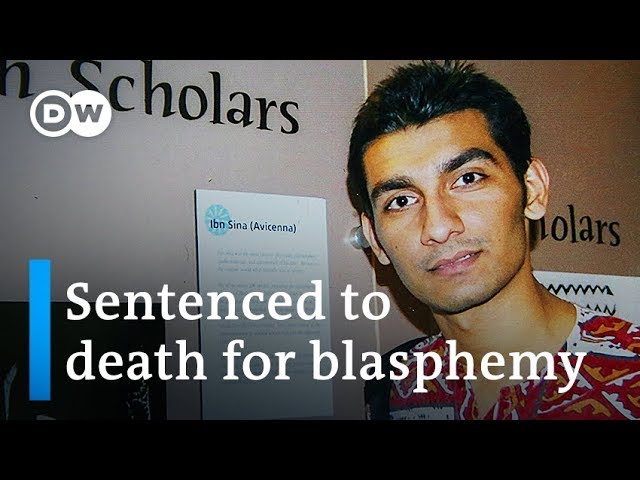

Junaid Hafeez was sentenced to death in Pakistan for making social media posts “insulting” Islam when he was a university lecturer in 2013.

The American government announced in mid-December that Pakistan is a country “of particular concern” given its record on religious freedom. The Pakistani government reacted angrily, and claimed that the Americans were “arbitrary” in their judgement. Apparently Islamabad failed to notice the mountain of material that the American government has acquired to support its “arbitrary” decision. And the Pakistani government has not been reading the newspapers, including those in Pakistan itself. If it did, it would find described a country where Hindus and Christians endure humiliation, persecution, and sometimes death, both from their Muslim government, and from Muslims meting out their vigilante justice against those who have been charged with “blasphemy.”

The story is here.

That charge of “blasphemy” is particularly terrifying because it is often made by those who are simply trying to get back at someone over a personal matter. In one recent case, a Muslim student accused Notan Lal, his Hindu school principal, of “making abusive remarks about the Prophet Muhammad”; the principal had to be taken into protective custody so as to save him from being lynched; his school was ransacked, a Hindu temple badly damaged, and the homes and shops of Hindus also attacked by maddened Muslims. It appears that the student had a grudge against Notan Lal over some school matter, and malevolently brought the charge of “blasphemy.” Even if the government ultimately finds insufficient evidence to convict Lal, he is still under a threat of death from a Muslim mob or even one Believer who wants to see Islamic justice done. Lal may not ever be able to return to his previous home or occupation.

The “blasphemy” case of Asia Bibi became known worldwide. She is the Pakistani Christian, who was harvesting berries alongside some Muslim women. They became enraged when Bibi drank water from a communal cup, thus “contaminating” it for Muslims. A heated argument followed, and the women then accused her of making disparaging remarks about Islam; she was promptly taken away by the police. On the basis of nothing more than those accusations, Bibi was sentenced to death. Eventually the Pakistani Supreme Court reversed her conviction. But she still could not be released, for her own safety, until finally a country was found that would take her. She was smuggled out of Pakistan to Canada, where no doubt she still must worry about Muslims recognizing her and carrying out the sentence they know she so richly deserves.

There was collateral damage from her terrible ordeal. Salman Taseer, the Muslim Governor of Punjab, who supported Asia Bibi throughout, was murdered for that simple decency by Mumtaz Qadri, one of his security guards. Qadri was executed, but 100,000 Pakistanis attended the funeral of this man whom millions in Pakistan regarded as a hero.

In Pakistan the government does nothing to stop the abduction, forced conversion, and marriage to much older Muslims, of young Christian and Hindu girls. These girls have no one to protect them. Even their families are threatened with trumped-up charges of “blasphemy,” should they even attempt to find their daughters who have been snatched so cruelly from them.

The tale of one Christian girl in Karachi is heart-wrenching:

Huma is a 14-year-old Christian girl from Zia Colony in Karachi, Pakistan. On the 10thof October, whilst her parents were out, she was abducted from her home and forced to convert and marry a Muslim man.

Though her parents received Huma’s conversion papers and marriage certificate – to a man named Abdul Jabar – the family are sure the papers are fake, due also to them being dated to the very same day the young girl went missing.

Recently, Huma’s abductor has threatened both her parents and their lawyer, Tabassum Yousaf, that he would accuse them of blasphemy. The High Court of Sindh lawyer has worked on many cases of forced marriage, and speaking with Aid to the Church in Need, she says that these threats are common. She explains that the abductors often say, “If you do not stop searching for your daughter, we will rip pages out of the Koran, place them on your doorstep, and accuse you of profaning the sacred book.”

It’s as horrifyingly simple as that: threaten to rip up pages of the Qur’an, leave them on the doorstep of any Christian parents who try to locate their kidnapped daughters, and they will then have a permanent death sentence hanging over them, to be carried out not by the government, but by maddened Muslims.

Another case recently publicized is that of Zafar Bhatti, who was falsely accused of blasphemy to prevent his work as a Christian journalist. He was arrested seven years ago after reporting on Christian persecution. Lahore Evangelical Ministries, explained how easy it was to frame him: “Somebody used his mobile to send a text against the Prophet. This became a blasphemy case against him. Insulting Mohammed means anyone can kill him. His guard attempted to kill him and somebody gave him poison.” Even if the government eventually frees him, his life is effectively ruined. He dare not return to being a journalist. At any moment he may be killed — even if he serves out his sentence, that may not be enough for those defending the honor of Muhammad.

What could the government of Pakistan do to change the behavior of those who wield as a weapon the baseless charge of “blasphemy”? It could continue with what it has been doing – that is, not much. Or Prime Minister Imran Khan, who has tried to portray himself as a “reformer,” but in the past has also made overtures to fundamentalists, could decide to stop trying to please both sides and come down firmly on the side of “reform.”

During his campaign for prime minister, Imran Khan not only defended blasphemy laws, but members of his party campaigned with known terrorists. He called for international laws to restrict “blasphemy,” a response to a Muhammad drawing contest in the Netherlands (the contest in the end was cancelled as a security risk). He was known as “Taliban Khan” for his apparent solicitude for fundamentalists. After Asia Bibi was exonerated by Pakistan’s Supreme Court, enraged mobs came out to protest. Khan then gave a much-praised speech, denouncing the protesters as “enemies of the state.” Khan’s party, the PTI, tweeted that Bibi would not be put on the “exit control list” (which would have prevented her from leaving the country), nor would the Supreme Court’s ruling be challenged. Within the hour, Khan’s government had reversed itself. It made an agreement with the protestors: Asia Bibi was put on an exit control list after all, and the government now said it would allow an appeal against the Court’s decision. But in the end, having allowed the mob their seeming victory, Khan’s government reversed itself again: Asia Bibi was allowed to fly to Canada; Khan weathered another huge protest led by Maulana Fazlur Rahman, who wanted him to resign. He retains what matters most – the support of the army.

It would take courage, in Pakistan, where many rulers come to a bad end (Zia ul-Haq, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Benazir Bhutto), to attempt to awaken some still small voice of conscience among the more advanced members of its Islam-saturated society. Khan’s an unlikely candidate, but he’s already been anathematized by the fundamentalists; nothing except his resignation will satisfy them, so having nothing more to lose, why not challenge them, and do so not alone, but in concert with other noted Pakistanis who deplore the misuse of the “blasphemy’ charge?

Khan might address the nation, noting that nothing had happened to the women who had falsely charged Asia Bibi with blasphemy. He could push for passage of a law that, in cases where charges of blasphemy were found to have been made in bad faith, would severely punish those making them.

Prime Minister Imran Khan could call for, and have his government assemble, a meeting of Muslim “notables” to discuss how the charge of blasphemy has been misused and why that matters not only to the immediate victims, but to that all-important “image of Islam” that must be upheld. Furthermore, every false charge of blasphemy undermines those that might be valid. Khan could thus present himself as a Defender of the Faith. He can make sure to have those “notables” selected from among those who have already indicated, like the late Salman Taseer, that they are disturbed by “blasphemy” wielded as a weapon for personal ends. He has the power to make the Pakistani media report enthusiastically on the meeting. He might even be able to persuade the Saudi Crown Prince, who remains keen to present himself as a “reformer” as well, to support such an undertaking. That would ensure favorable coverage in that considerable part of the Arab press that is owned by, or receives subsidies from, the Saudis.

Let Pakistanis learn in detail about those who kidnap, forcibly convert, and marry off young Christian and Hindu girls to much older Muslims, and who then threaten the distraught parents of these girls to call off their searches, or be faced with trumped-up claims of “blasphemy.” In the case of the 14-year-old Christian girl, Huma, already discussed above, the threat by her abductor was to rip up pages of the Qur’an and put them on the parents’ doorstep unless they stopped trying to find her; if that threat had been carried out, it would almost certainly have been a death sentence for the parents. Other examples of trumped-up charges, such as the Christian journalist Zafar Bhatti, now in his seventh year of a long prison sentence could also be adduced – a dozen such cases might be discussed by the “notables” whom Khan would have assembled, and be reported on by representatives of the world’s media. Bhatti, remember, was convicted of blasphemy, based on a message denigrating Muhammad that was sent on the mobile that had been stolen from him. Prime Minister Khan should ask the Pakistani people to use their common sense. How likely is it that any non-Muslim in Pakistan would dare to rip up the Qur’an, or mock Muhammad on his mobile? A moment’s thought would lead to the ineluctable conclusion: it would in both cases have been inconceivable. Let those “notables” end the meeting with the adoption of a resolution that would deplore the manufacturing of “blasphemy” charges for personal ends – as that student who charged his principal, Notan Lal, with “blasphemy” because he simply didn’t like the way the principal had treated him.

Such a conclusion to the meeting would set inevitably set off the usual mob protests led by maddened clerics. But the last big protest, that of Fazlur Rahman’s “Azadi March” on Islamabad to force Khan’s resignation, was simply allowed to fizzle out, and Khan remained in power. It should be no different now.

Can such a meeting, to start “reform” rolling by coming down hard on those who abuse the blasphemy charge, have much of a chance?

No, not now. Imran Khan is still scared of the fundamentalists. He does not agree that they have already done all that they can do against him, with their interminable marches. He knows what fanatical Muslims did to Benazir Bhutto and to Salman Taseer.

But we can allow ourselves to dream – strange things happen every day — that the celebrity prime minister of Pakistan will eventually find it within himself to break totally with the fundamentalists who, after all, have already broken totally with him.

First published in Jihad Watch.

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link