“People insist on fairness.” In the former USSR — and in today’s US

by Lev Tsitrin

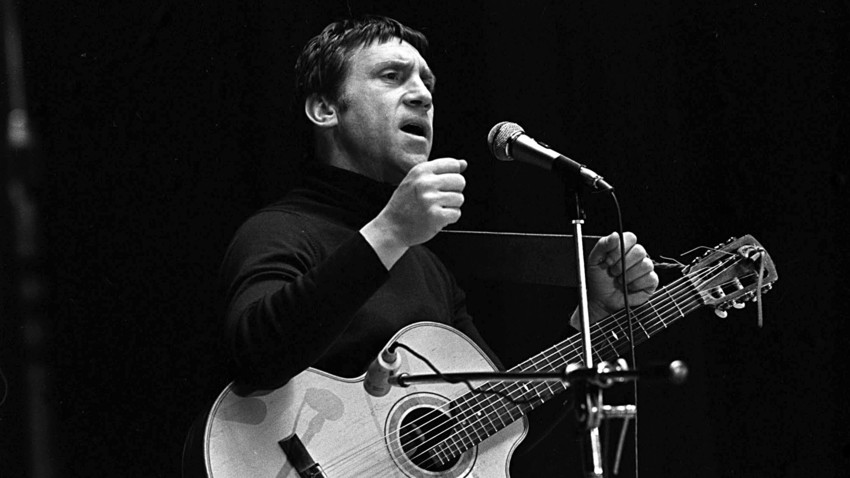

Among those who expressed the deep-seated yearnings of the Soviet soul, no one was more beloved than a poet-singer Vladimir Visotsky. Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov are household names in the West, yet both were suppressed in the USSR, and perhaps a bit too cerebral to be widely embraced in warm adoration by a common man. Visotsky, on the other hand, spoke (or rather, sang) in a way so accessible to all, yet so emblematic of the bleak Soviet reality that his songs instantly resonated, both on the emotional, and on the intellectual levels. His tapes were copied and re-copied, the quality of sound deteriorating to the point where one had to strain to distinguish the words, yet any Soviet household that had a tape recorder boasted his songs as the greatest treasure in its collection of tapes. The songs were not ostensibly anti-Soviet; yet they exposed the hypocrisy of official Soviet optimism, insidiously poisoning it. They were subversive — not in any obvious way, but simply because they spoke an honest truth readily recognized by listeners who were sick and tired of the official propaganda. Unlike Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov, Visotsky was never persecuted, arrested, or exiled. He worked at a Moscow theater as an actor; his wife was French, and unusually for the USSR, he freely traveled abroad. Among his ardent fans was Brezhnev. When he died, aged 42, in 1980, the government suppressed the news for days, for fear it would disrupt the Moscow Olympics.

His songs often dealt with the mundane, like the one poking at the officially-proclaimed Socialist equality (and the Marxism-promised abundance that contrasted with everyday scarcity of goods and food) — by describing a mood in a line to an eatery, or a food store:

but people — they unhappily kept grumbling,

but people — they on fairness insist:

“we were ahead in line — so why behinders

already eat? It is unjust!”

“I beg be calm,” replied Administrator

“I beg you leave, and don’t wait any longer,

Those who eat — they are the deputies.

while — begging pardon — you are nobodies!”

The stanzas (which in the Russian original rime nicely, and have a beautiful beat) keep repeating, varying mainly in the specific nomenclature of “those who eat” — “deputies,” “delegates,” “foreigners” — the privileged classes in the officially equal-for-all Soviet Union which, for all the talk of equality, had a system of restricted distribution points (or “special stores,” as they were called) for “nomenclatura” only — the Communist apparatchiks and suchlike higher-ups.

Perhaps it is because of a sheer inertia of being an ex-Soviet that I “on fairness insist,” and find its absence in this land of “liberty and justice for all” profoundly disappointing — along with the absence of the coverage of this absence in the mainstream media. So, I “keep grumbling.”

Those absences — and the hypocrisy that fills the emptiness they cause, are glaring. The Constitution forbids the government from abridging citizens’ speech — yet the government brazenly ignores this check on its powers and openly does what the Constitution forbids it from doing, abridging speech by officially blocking individuals’ access to the mainstream “marketplace of ideas” that are our nation’s libraries and bookstores to individuals, keeping it open only for corporations.

Recently, in a particularly blatant display of hypocrisy — since it is the Library of Congress that blocks author-published books from reaching their audience — the American Library Association has announced a “Banned Books Week,” inviting us to “read a banned book.” Is the American Library Association unaware that the systemic banning of books is done by the chief library in the land? It is incredible how the librarians speak out of both corners of their mouths, encouraging reading while blocking the publishing of books that should be read! Though in fairness, librarians do not have a monopoly on hypocrisy — PEN America is every bit as hypocritical, protesting against “bans” on corporate-published books — but not the suppression of author-published ones. I guess both the librarians, and PEN America sit deep in corporate publishers’ pocket.

Equally symptomatic of the absence of fairness was my inability to fix the absence of “liberty for all” by resorting to “justice for all” — federal judges kept replacing in their decisions my, and the government’s lawyers’ argument with the utterly bogus argument of judges’ own concoction so as to justify government-instituted regimes of censorship and crony capitalism. When I sued judges for fraud in order to restore to federal courts the “justice for all,” they justified their behavior by the self-given, in Pierson v Ray, right to act from the bench “maliciously and corruptly.” To them, the behavior that is contrary to “due process” accords with “due process;” judges’ solution is to make “due process” Kafkaesque.

As Kafkaesque is mainstream media’s attitude to this problem. No journalist wants to touch it with a ten-foot pole. My town’s radio station, WNYC, “the New York public radio” touts itself as practicing “independent journalism in the public interest” and therefore seems to be a perfect venue for shedding the light on judicial fraud (for what is more in “the public interest” than honest governance?) Yet getting it to do it is about as tough a task as getting inside Kafka’s “Castle.” Thought the station hosts a daily, two-hour “Brian Lehrer show” dedicated to politics, and a discussion of judicial chicanery would be a perfect fit, Brian refuses to reply to me. Because of my persistence in asking WNYC for their reason for not covering judicial fraud (though why would this branch of government be, uniquely, beyond journalistic scrutiny?), they blocked my email addresses and phone numbers.

So I have to get creative. A couple of weeks ago Brian dedicated a segment to interviewing his brother Warren (who is a noted book artist who elucidates the meaning of the text by using creative typography), and to advertising an event dedicated to publication of a book of poetry that he set in type. I went, and gave Warren my contact info, asking him to pass it on to Brian (to my surprise, Warren was well versed in the problem of gatekeepers to the marketplace.) Yet, there was no answer from Brian. I emailed Warren, again asking him to forward my email to Brian. No answer from Brian. To Brian, telling the wider New York area about a poet’s reaction to Covid restrictions, and a graphic artist’s reaction to this poem is fine — but giving the same amount of air time to the fact that a full third of US government gave itself the right to be malicious and corrupt, cheating the public out of justice by underhanded practices, and ruling the land like monarchs? No way! A brother is a brother — I get that. But isn’t the institutionalized, systemic, and entrenched judicial fraud also important? Not to WNYC’s politics talking head!

WNYC also produces a nation-wide broadcast titled “On the Media,” a program dedicated to understanding the trends in journalism itself, and they recently did a three-part series on judges, done with ProPublica — which, as is typical of ProPublica’s naive reporting that seems to insist on misses the point, failed to ask the key question that I keep asking: how is it possible for a judge to decide a case the way he want to, despite facts and law? How does this square with “due process”? Of what use is “the rule of law”? Being an investigator of journalism, “On the Media” is the perfect place to clearly articulate journalistic attitude towards the issue of proper judging.

I recently had a brief encounter with the host, Brooke Gladstone, who told me to drop off my materials at the station’s office. Easier said than done: I mailed a package to her, but getting no reply (for an entirely legitimate reason, as it turned out), I printed out another set to deliver in-person (I had to be in Manhattan anyway, to attend a public lecture given by a friend) — but on learning my name, they refused to take it — or even to talk to me. For the “New York Public Radio,” not everyone is “public.” As in Visotsky song, there are “deputies” and “delegates” — and the “nobodies.” Still, I am not losing hope. I opened a brand-new email address, describing the situation to Brooke; she advised me to e-mail the materials to her. We’ll see what comes out of this — but the issue is clearly important. The stakes for the country are extremely high, and I have no intention of letting go. (As I write this, WNYC is doing its fall fundraiser, asking listeners for money — and to listen to the honey that’s dripping out of my radio, the station is a paragon of honest reporting. I wish!)

Interestingly, the judicial chicanery which the mainstream media refuses to face and report is not something that the legal profession is unaware of, or is shy discussing. While academics do not necessarily go after judicial swindling done in lower courts (though the title of an article by Yale professor Susan Rose-Ackerman, “Judicial independence and corruption” sounds tantalizing), the Supreme Court is a regular punching bag for academics, like in a book titled “Supreme Myths: Why the Supreme Court Is Not a Court and Its Justices Are Not Judges” by Eric Segall, law professor at Georgia State who “explains why [the Supreme Court] makes important judgments … based on the Justices’ ideological preferences, not the law,” or the recent New York Times best-seller, Texas law professor Stephen Vladeck’s “The Shadow Docket: How the Supreme Court Uses Stealth Rulings to Amass Power and Undermine the Republic.”

I recently attended a conference on “Nationwide Injunctions” held at NYU Law School that was dedicated to critiquing the recent, and highly controversial, practice of judges extending the relief requested for a specific locality and circumstance to the entire nation. Judge Garaufis of the Eastern District Court of New York headed the first session that debated whether the practice should even be an issue; Professor Vladeck headed the panel on the remedies. It was real fun — law professors are sharp and quick-witted, and have plenty of vivid anecdotes to illustrate their points. Professor Tierney of Harvard (who was Maine’s Attorney General before becoming an academic) regaled us with a lively explanation of how “judge-shopping” (that is a necessary part of getting a nationwide injunction) works. States’ attorneys general (who are invariably ardent partisans) pool their knowledge to locate a federal judge whose ideology aligns with theirs, and delegate the filing of a case to an attorney general of a state under that judge’s jurisdiction. This is necessary because the main hurdle is to establish standing (i.e. the right to sue) — and the standing, as Professor Tierney explained in a memorable comparison, is like an accordion: either shut tight, or opened wide — “depending on the music the judge wants to hear.”

This accorded well with my experience of the arbitrary nature of judging, so using as a segue an anecdote told by another panelist, Judge Sands (who on the way to the conference got an earful from his Uber driver on how awful the judges are, and how badly the system sucks), I described in Q&A the reasons for my total sympathy with the Uber driver, and to offer my solution — of adding judges’ use of their own, “sua sponte” argument to the criteria of judicial misconduct, thus nipping this fraudulent practice in the bud — solving a whole plethora of problems. Judge Sands took this head-on, explaining that on detecting an argument that the parties avoided discussing, he directs them to do so, telling them to fight it out — but does not supply his understanding of the matter in the decision, or replace the argument filed by parties (as the judges did in my case).

Since Judge Garaufis adjudicated one of the cases in which I sued judges for fraud (he ruled that judges’ substitution of parties’ argument in their decisions with a bogus argument of judges’ concoction constituted “classic exercise of the judicial function,” no less) and I mentioned that bizarre opinion of his, it was interesting to watch him. He sat so as to face the corner of the room, rather than its center where I sat, so as not look at me, I suspect. I, of course, said nothing to him directly — nor did he address me. But I left the conference with a philosophical observation: seeking, upon my arrival, a certain small room equipped for physiology, I discovered another gentleman intent on the same purpose (great minds think alike, I guess!). As I realized when the participants of the panel were announced and seated, that other gentleman was Judge Garaufis — so at least in some ways we, commoners and judges, (or “delegates” and “nobodies” in Visotsky’s parlance) are still equal!

When I got home, I wrote to Professor Vladeck — who courteously replied that he appreciated my “important questions;” one of the organizers of the event was kind enough to tell me that my comment was “spot on,” it being about the essence of democracy, So now I need to focus on making journalists understand what the law professors know full well — that the way judging is done is often unsatisfactory, and that how to do it aright is a legitimate subject for journalistic inquiry and public discussion.

It turns out that not only Soviets (and ex-Soviets) crave after fairness and justice. Americans — be they Uber drivers, or law professors, do too. Journalists (WNYC journalists including) are an exception — and need to be added to the list of those who think that the “malicious and corrupt,” “sua sponte” method of judging is not right, no matter how convenient for the judges.

So I’ve got to keep trying to convince them of it. Perhaps because, like all Soviets, I love Visotsky, I do “insist on fairness,” and cannot bear the thought that while I am indefinitely “waiting in line,” the corporations — who by law should not have any advantage over me, “already eat.” In this land of much-trumpeted equality, I refuse to be a mere “nobody.”

Lev Tsitrin is the author of “Why Do Judges Act as Lawyers?: A Guide to What’s Wrong with American Law”