Problems, Real and Imagined

by Phyllis Chesler

The American professor asked all her students to share a little bit about themselves. The student who had recently arrived from Afghanistan said this:

“I am so lucky. With my passport pasted to my body, I walked and ran under a hail of Taliban whips and guns to the airport. Somehow, miraculously, some members of my family also kept up, and we managed to jump into the filthy sewer that surrounded the airport. I found the gate to the country that was going to offer me asylum. This took more than two days. I did not think we would get out alive, but we did. I am so grateful to be here. But I don’t know how long my luck will last.”

The next student, born in America, said this:

“I am really suffering, as I wrestle with my gender identity. I definitely think I’m queer but then what? Am I non-binary or a lesbian? What if I’m a trans-man? What if all the meds and surgeries that I need are too expensive or not covered by my parents’ insurance? What if I lose some friends over this or am discriminated against at a job or even here at the university?”

The Afghan student, a woman, has faced the most brutal misogynist tyranny. Her troubles are far from over in terms of obtaining citizenship anywhere on earth. The American student is concerned only with herself and with her identity. She does not seem connected to the issue of abortion and legally forced pregnancy/forced motherhood or to the still existing plagues of rape, incest, domestic violence, and the trafficking of women, in America, all of which can afflict her. Nor is she concerned with what happens to others in the world such as war, exile, homelessness, mental illness, violent crime, racism, etc.

What have we done to our coming generations? Can this ever be turned around? If so, how?

Given young people’s addiction to the internet where naught but misinformation and disinformation, as well as online peer pressure and fake “friendships” prevail (maybe adults are equally enthralled by the internet)—an addiction which has profoundly limited our attention span. Increasingly, people choose audiobooks and movies as their preferred go-to venues for information.

I recently met a young woman in her twenties, a college graduate, who was proud of the fact that she had not read any book written before 1985. But who am I? I am someone whose young granddaughters know more about Instagram, TikTok, and avatars than I do.

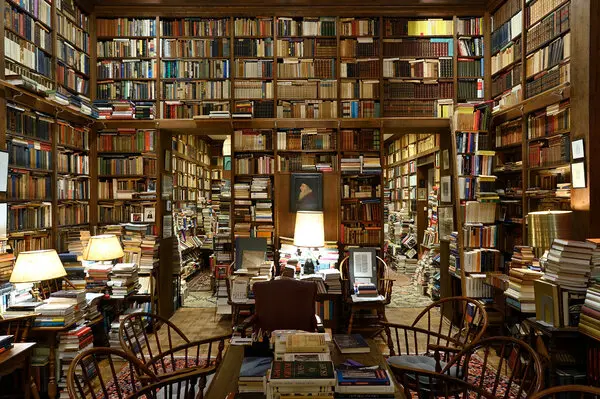

I am a member of all those generations who once wrote their books by hand (I did) or on a typewriter (I did) or on a scroll (sounds sacred, but before my time). I am one of those who love physical books: Holding them, smelling them if new, underlining passages or attaching my comments on post-its (I’m certainly guilty). I don’t even like to read on Kindle. I lust for high-ceiled two or three story libraries and would happily live in one if I could.

My breed is dying out. I would like to pass along all that I know—but how? It is not valued, not wanted, by those who need it most—like that American student above, whose privileged concerns are entirely personal, immediate, self-referential.